1. ERIC MINGUS-DAVID AMRAM-LARRY SIMON-GROOVE BACTERIA, Langston Hughes: The Dream Keeper (Naxos of America)

1. ERIC MINGUS-DAVID AMRAM-LARRY SIMON-GROOVE BACTERIA, Langston Hughes: The Dream Keeper (Naxos of America)

There have been many recordings featuring the works of the great Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes (1902-67), including Hughes’ own spoken word recordings, some with musical accompaniment. Perhaps the most well-known is the 1958 MGM release Weary Blues, featuring Hughes reciting his poetry over a jazz soundtrack composed and arranged by Leonard Feather and Charles Mingus. A more recent offering was Laura Karpman’s GRAMMY Award winning Ask Your Mama, featuring her original musical setting of Hughes’ epic poem Ask Your Mama: 12 Pieces for Jazz.

Langston Hughes: The Dream Keeper is more closely related to the aforementioned 1958 recording in more ways than one. Not only does it combine poetry with jazz, but the narrator is none other than Eric Mingus, the son of Charles Mingus. The younger Mingus, a prominent jazz bassist and vocalist, utilizes these talents to full effect while performing Hughes’ poetry. The music was arranged and directed by jazz guitarist Larry Simon, who founded the popular Beat Night series in New York as well as the JazzMouth festival in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to promote music and spoken word collaborations. Also contributing to the project is noted composer/conductor David Amram, who played with Charles Mingus, pioneered the first-ever public Jazz/Poetry reading in NYC with Jack Kerouac, and collaborated with Langston Hughes on the cantata, Let Us Remember, where he learned about Hughes’ own forays into jazz-poetry. When these three musicians (Simon, Amram and Eric Mingus) came together at one of the Jazzmouth festivals, they were easily sold on Simon’s idea “of making a CD honoring the poetry and the life of Langston Hughes,” and worked diligently to “honor every word that we heard and every musician with whom we [had] played.” …

‘The Dream Keeper,’ Eric Mingus, David Amram, Groove Bacteria, from Langston Hughes: The Dream Keeper

The Dream Keeper was recorded in 2012 towards the end of Barack Obama’s first term as POTUS, and released just prior to Donald Trump’s inauguration. If released just a few weeks later, I wonder if Simon would have changed the order of the tracks to end with “Democracy,” the opening lines of which read: “Democracy will not come/Today, this year/Nor ever/Through compromise and fear.” In any case, this is a first-rate project. I might even suggest that Mingus’s heartfelt delivery, with its soulful timbre and nuanced rhythms, is even more impactful than the recordings made by Langston Hughes. To use a phrase from Amram, Eric Mingus knows how to realize and pay homage to “the music that is already in the spoken word.” Highly recommended!

Click here for the complete review by Brenda Nelson-Strauss at Black Grooves.org

***

2. GUY DAVIS & FABRIZIO POGGI, Sonny & Brownie’s Last Train: A Look Back At Brownie Mcghee & Sonny Terry (M.C. Records)

What Guy Davis and Fabrizio Poggi have done on this loving tribute is to capture the joy and passion coursing through Sonny and Brownie like life’s blood. There will doubtless be records more heralded than this in 2017, but there will be few, if any, as electrifying as this all-acoustic romp through 11 trademark S&B numbers (a couple of S&B originals and others by Big Joe Williams, Elizabeth Cotton, Robert Pete Williams and Big Bill Broonzy along with traditional items such as “Midnight Special” and “Take This Hammer,” a tune associated with Lead Belly). The lone new number is Davis’s album opening remembrance, “Sonny & Brownie’s Last Train,” a choogling fusillade of whooping harmonica, sprightly guitar picking and slide work, and Davis’s speaking-singing vocal recounting Sonny and Brownie’s last ride into the sunset, you might say, on a locomotive the conductor says is “just for Sonny and just for Brownie/you can’t get on board.” Apparently, Davis was making up the lyrics on the spot, which maybe accounts for the deep feeling in his voice at the end when he speaks into the mic, “Goodbye, Sonny, goodbye, Brownie. See you on the other side.” He’s in pretty deep already. Complete review here…

***

3. BEOGA, Before We Change Our Mind (Beoga Music)

3. BEOGA, Before We Change Our Mind (Beoga Music)

Over the course of four albums the County Antrim-based Beoga has risen into the top rank of Ireland’s new wave of tradition-oriented bands. The Pogues’ late, much lamented Philip Chevron once described his band’s music as “traditional Irish music with a punk rock kick in the arse.” Beoga’s music is not quite that, but here and there you will detect the spirit and energy of the Pogues and Stiff Little Fiingers within a framework redolent of the Chieftains and of the adventurous side of Michael McGoldrick. Following by five years Beoga’s acclaimed live CD/DVD, Beoga Live at 10, Before We Change Our Mind moves away from the pastoral jazz-influenced sounds of 2007’s Mischief and 2010’s The Incident in favor of a strong Irish ensemble sound bursting with intensity and ideas, not entirely devoid of jazz flourishes, but the piano that brought an added soothing dimension to those earlier albums is in a more forceful role here. Expertly steering the live sessions from behind the board, and crafting a tight, rich soundscape, is producer Michael Keeney (whose credits include Ed Sheeran, Bonnie Raitt and Lisa Hannigan, among others), who understands these musicians and their aims and so does what good producers do and stays out of their way. Complete review here…

‘Echoaid,’ Beoga, from Before We Change Our Mind

***

4. CHUCK BERRY, Chuck (Dualtone)

Late-career albums by rock ‘n’ roll’s pioneers have been spotty at best—consider the embarrassments of Bo Diddley and Carl Perkins—but two of the orn’riest of the lot, Jerry Lee Lewis and now Chuck Berry, have revealed undiminished powers in their antiquity. In the latter’s case, Chuck (announced as his final album months before his death on March 18) is more than impressive—it offers genuinely stunning moments as Berry turns back the clock with impunity. Backed by his club trio The Blueberry Hill Band supplemented by his two guitarist sons and daughter Ingrid on harmonica and joining in vocally on a slow burning blues love tune, “Darlin’,” plus guest guitarists Tom Morello, Nathaniel Rateliff and Gary Clark Jr. (he adding tasty, incisive soloing to the propulsive album opener, “Wonderful Woman”), Berry supports his engaged, commanding vocals by cutting out on guitar as only Chuck Berry can play the instrument. Items such as classically styled Berry rockers (“Big Boys,” “Lady B. Goode), a grinding blues cover of the pop standard “You Go To My Head,” and a slinky, reggae-tinged “Jamaica Moon,” are potent exercises, bursting with life and enhanced, sometimes poignantly, by solid sonics. Witness an unforgettable final testament. David McGee

‘Wonderful Woman,’ Chuck Berry, from Chuck

***

5. NOAM PIKELNY, Universal Favorite (Rounder Records)

5. NOAM PIKELNY, Universal Favorite (Rounder Records)

This is one of those occasions when the general public should have access to materials record companies or independent artists send out with CDs, in this case the press release Rounder included with virtuoso banjo man Noam Pikelny’s fourth solo album, Universal Favorite, a project featuring only the artist, his voice and his instruments. Best known as one of the barrier breaking Punch Brothers, Pikelny’s solo work has always been fascinating on multiple levels, and herein he again opens ears to the possibilities of tone and texture the banjo has too often and mistakenly been accused of not possessing. He does this not merely by technique but in his choice of instruments, all with fascinating histories. Seven of the 11 tracks find him employing a 1941 Gibson Style 7 banjo with a Robin Smith 5-string neck (“…found in the 1980s in a pawnshop in Johannesburg, South Africa, and repatriated back to the U.S.”); on two tracks he opts for the truly exotic 1928 National Style 1 Tricone Plectrum 4-string guitar that Pikelny discovered one expert assessing as having “no musical purpose” when it was introduced, and adding further, “that remains true to this day.” Pikelny’s reaction to this appraisal was to snap it up for use on his album.

‘Folk Bloodbath,’ Noam Pikelny, from Universal Favorite

“Each of these instruments has a unique story and has known the world much longer than I have,” Pikelny says. “Picking them up makes me feel more connected with generations that have come before. Perhaps this bond with old instruments that are filled with character and charisma makes performing solo feel less lonely.” Complete review here….

***

6. EMERSON EADS ET AL., Mass For The Oppressed Review by Joseph Newsome (May) (Emerson Eads Music)

6. EMERSON EADS ET AL., Mass For The Oppressed Review by Joseph Newsome (May) (Emerson Eads Music)

In his remarks at a 1962 dinner honoring Nobel Prize winners, President John F. Kennedy famously said that he believed the assemblage before him to be “the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” In the exalted history of choral music, increasingly marginalized by today’s secular society, one can seek parallels for Kennedy’s characterization in the choir gallery of the Cappella Sistina, where Josquin des Prez refined his craft, or England’s Chapel Royal, where in his brief life Pelham Humfrey defined Restoration choral traditions. There is in the congress of composer, text, and the art of writing for massed voices a power that is unique in music, an energy that pulses through notes, words, and voices with a directness that can be neither duplicated nor diminished. It is this creative electricity that charges through the strains of des Prez motets and Humfrey anthems—and through every bar of American composer Emerson Eads’s Mass for the Oppressed. President Kennedy understood the isolation of inspiration, but he also knew that one can transcend one’s own society only by embracing and fully participating in it, enduring tragedies with hope for triumphs. In Mass for the Oppressed, Eads transforms reflections on inhumanity into sounds of great beauty not by commenting on misfortune but by communing with it. This is music that ignites emotional wildfires, fueled by the ingenuity of an artist who, like Jefferson, engages his world with a keen mind and uncommon depth of feeling. Complete review by Joseph Newsome here…

Kyrie for Mass for the Oppressed by Emerson Eads. Soprano, Tess Altiveros; mezzo-soprano, Toby Newman; Barry Banks, tenor, and bass-baritone, David Miller, join forces with Emerson Eads and the University of Notre Dame’s Concordia Choir and Ritornello Orchestra for a world premiere, live concert recording of Emerson Eads’ Mass for the Oppressed. Written in response to the release of four Native Alaskans, known as The Fairbanks Four, from prison after eighteen years of wrongful incarceration. They were released in December of 2015 with no chance to seek any reparations from the state of Alaska.

***

7. EDNA GALLMON COOKE, My Joy: Rare Recordings 1948-1966 (Gospel Friend)

Edna Gallmon Cooke may be one of the most underappreciated female vocalists of gospel’s Golden Age. Although her voice was small when compared to belters like Mahalia Jackson, Emily Bram-Bibby and Ernestine Washington, what Edna Gallmon Cooke lacked in volume she made up for in finesse. She stirred church congregations by starting her performance soft and slow and building to a fiery crescendo. She knew when to shout, when to drop into a bluesy disposition, when to evangelize and how to work with accompanying singers. It didn’t matter whether it was a young people’s choir, a male choir, or a quartet—Madame Cooke was as comfortable with them as she was singing solo. And for recording short song-sermonettes, she was a pioneer. Complete review by Bob Marovich here…

‘Come On Let’s Run to Jesus,’ a live performance by Edna Gallmon Cooke on TV Gospel Time, with introduction by legendary gospel vocalist Brother Joe Ma

***

8. DOYLE LAWSON & QUCKSILVER, Life Is a Story (Mountain Home Music Company)

That life is a story will come as no surprise to bluegrass legend Doyle Lawson’s fans. Since forming his first Quicksilver incarnation in 1979, Lawson has made life’s big issues—love, spirituality, commitment– his bread and butter, and so it is on this masterfully realized project. No sugar coating here: In the gentle, resophonic-driven shuffle of Harley Allen’s “Little Girl,” domestic abuse—and an ensuing murder-suicide–are graphically described as a prelude to an enduring lesson in love an orphaned daughter learns from her caring foster family. “Life of a Hard Workin’ Man,” driving and harmony-rich, describes soul numbing clock punching as chillingly as Springsteen did in “Factory.” In “Guitar Case,” a poignant bluegrass ballad courtesy Donna Ulisse, a restless picker reluctantly leaves the woman he loves to embark on a vital journey of self-discovery. The touching finale, augmented by Stephen Burwell’s tender fiddling, is beautifully understated for maximum impact, much as the band did in “Little Girl.” Sometimes love does conquer all, as in the western swing-influenced ballad “Love Lives Again” and gloriously in the soaring, gospel quartet-styled missive, “What Am I Living For.” The sonics’ live immediacy underscore the group’s intense emotional investment in these tales. David McGee

Doyle Lawson talks about his new album Life Is A Story and the song ‘Life To My Days’ written by Jerry Salley, Lee Black and Devin McGlamery.

***

9. JIMMY SCOTT, I Go Back Home: A Story About Hope And Dreaming (River Records)

9. JIMMY SCOTT, I Go Back Home: A Story About Hope And Dreaming (River Records)

“Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,” Jimmy Scott sings in “Motherless Child,” cushioned by Joey DeFrancesco’s soulful organ and stately, mournful strings. To that point, that a singer as transcendent as Jimmy Scott ever existed does seem like something out of a dream. A genetic disorder left him with a pre-pubescent voice that made the younger Scott essentially genderless, exotic and riveting. Although in his career he worked across generations with Sarah Vaughan, Ray Charles (who produced his 1951 album, Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool), Lou Reed and others, and had a late-life run of good professional fortune thanks in large part to being championed by the great songwriter Doc Pomus, the brass ring of household word stardom always eluded him. He was maybe too good for the mainstream as it evolved and real singers were left behind in the autotune era. Obscurity followed him around, always beckoning when better things seemed on the horizon. But Jimmy Scott, who died on June 12, 2014, was a beautiful soul with a holy spirit. In 2009 he was sought out by a German producer, Ralf Kemper, whose self-professed mission was to make one last great album with Jimmy before the otherworldly artist was called home. The recordings were part and parcel of a larger project that includes a documentary about Jimmy, hence the lapse in time from the recordings to this album’s release.

‘The Nearness of You,’ duet featuring Jimmy Scott and Joe Pesci, from I Go Back Home

What you hear at the outset, on “Motherless Child,” is Scott not always in full command of his voice but always in full command of his soul and his feeling for the lyrics. It’s a haunting track, all the more so for being so stark, so determined to let Jimmy tell his story as unburdened as possible by other atmospheric flourishes. “The Nearness of You” brings him closer to his classic performances of yore, both in its lush arrangement and especially in the singer’s passion for the moment (Joe Pesci—yes, that Joe Pesci—makes the first of his two appearances on the album here, in feisty duet passages with Scott). There are some curious oddities: the Gershwins’ “Someone to Watch Over Me” has a beautiful, romantic arrangement; touching, blues-tinged piano work by Kenny Barron, a winsome vocal by Renee Olmstead that is both longing and hopeful, but no Jimmy Scott in evidence. “I Remember You,” the 1941 evergreen penned by Johnny Mercer and Victor Schertzinger for the Broadway show The Fleet’s In, rolls out with a bossa nova feel, a cool flugelhorn solo by Arturo Sandoval, some nice, understated guitar work deep in the mix by Oscar Castro Neves, a sensuous, captivating vocal by Monica Mancini, but again, no Jimmy Scott in evidence (although he is the principal vocalist on a weird bonus track remix of “I Remember You” that is some kind of cross between Jimmy backed by a Pied Pipers-like chorus and various odd rhythmic boom-chicka sounds and voices). But for the most part Jimmy is present and accounted for, and does splendid work on another duet with Pesci on “Folks Who Live on the Hill”; on Irving Berlins’s “How Deep Is The Ocean” (with Kenny Baron and Oscar Castro Neves again contributing empathetic solos—Barron working some invigorating improvisations on the melody—and Peter Erskine, as he does throughout, adding the feathery touch on brush drums); and on a knowing treatment of “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool,” on which Scott’s all-too-wise reading is augmented by James Moody’s tart sax solo and DeFrancesco’s appropriately restrained organ punctuations. No one will claim I Go Back Home is on a par with Jimmy Scott’s classic albums, but the instincts and gifts that made him a singular voice in his younger years remain undimmed by time, and even the infirmities of age are often swept away as songs flower. A timeless question remains in force: What’s not to love? David McGee

***

10. PAUL KELLY, Life Is Fine (Cooking Vinyl)

Those fans fearing Paul Kelly had been spending too much time in the Australian heat after his somber 2016 releases (Seven Sonnets & A Song, musical settings of Shakespeare’s poetry; and his 2016 Deep Roots Album of the Year, Death’s Dateless Night, a collaboration with Charlie Owen on songs they sang at funerals), listen up: Life Is Fine finds Kelly mighty fine indeed—upbeat, tuneful, energized. Backed by many of the musicians he’s worked with on the road these past two decades, Kelly is in his wheelhouse here, examining relationships with heart and wry humor. As lovers come and go Kelly portrays himself alternately as forlorn (“Rising Moon,” despite its seething intensity); buoyantly lovestruck (“Finally Something Good,” a classic pop-rock item with lyrics emanating sunshine powered by a driving arrangement fueled by Cameron Bruce’s piano and Ashley Naylor’s sizzling guitar); and hilariously lusty, “a man with a plan” to seduce his woman with ”wine in the bottle/paella cooking in the pan/Elvis on the stereo…” Kelly’s near-deadpan delivery over a raucous rock ‘n’ roll assault (complete with a delightful, cheesy Farfisa organ solo) makes the whole setup seem helplessly hopeful but the sincerity of his feelings and the certainty of his conquest makes a riot of the whole enterprise. Lest Kelly be taken to task for a too male-centric view of the game of love, he gives something approaching equal time to the distaff point of view in the stomping, dirge-like “My Man’s Got a Cold,” in which sassy Vika Bull demonstrates a bedside manner lacking much in empathy or embracing the Hippocratic oath (“Well, if he don’t come ‘round soon/I just might have to put him down…”); Vika’s sister, Linda Bull, is in similar put-down mode on the more pop-ish “Don’t Explain,” wherein she practically exults in warning a wayward lover against assuming she’s going to be available next time he comes ‘round (“But if one night you’re lonely/and I have other company/don’t complain, don’t complain…”) If Vika’s and Linda’s turns on Life Is Fine are among the album’s pleasant surprises, the biggest surprise of all is Kelly’s continuation of one of Roy Orbison’s most fevered imaginings in “Leah: The Sequel.” Kelly’s swaggering, bluesy tune, awash in a tropical feel, finds the presumably drowned protagonist of “Leah” not living with the oysters he hoped to scavenge for pearls but alive and well, with those pearls in hand and Leah at his side in some undisclosed location where they have “a hut and a boat by the sea…” and the guy toils in Leah’s father’s cannery. The narrator suggests the girl of his dreams has a ten-year plan that will free him from dad’s cannery for good, and end his days of pearl diving as well—dark doings are afoot. In a nice touch, the ghostly harmonies of the Bull sisters evoke the melody and ambience of Orbison’s nightmare saga.

‘Finally Something Good,’ Paul Kelly, from Life is Fine

The sweet reminiscence of an old love affair in “Letter In the Rain” and the joyous ode to “Josephine” represent Kelly at his most lyrical and tender. To put a fine point on this uplifting chronicle, Kelly turns to the poetry of Langston Hughes, to whose “Life Is Fine” he adds an assertive vocal framed by Cameron Bruce’s low humming organ and Ashley Naylor’s swooping slide guitar setting the stage for his album ending cry, his voice soaring off into the distance as he announces, “Life is fine! Fine as wine! Life is fine!” Repeat after Paul. (Note: for another take on Hughes’s “Life is Fine,” check the album closing version of Eric Mingus and David Amram’s Langston Hughes: The Dream Keeper, #1 on this year’s Elite Half-Hundred.)

***

11. RICK SHEA & THE LOSIN’ END, The Town Where I Live (Tres Pescadores)

Essentially a folk singer with a hearty voice, a sure feel for country-flavored blues and given to vivid, detailed portraits of people and places in the manner of Tom Russell, California-based veteran Rick Shea offers a folk-flavored gem as wise and powerful as Tom Paxton’s 2015 triumph, Redemption Road. Like all outstanding folk writers, Shea knows the land and its human inhabitants are inseparable, and the former is predictable only in doing unpredictable things to the latter. So the album opening toe-tapper, “Goodbye Alberta,” although spiced with a bit of Tex-Mex flavor in the form of multi-instrumentalist Stephen Patt’s accordion, might well be am emotional farewell to Alberta, Canada, or to a doomed relationship with a living person. Actually, the first three songs—including “The Road to Jericho” and the twangy, Cash-like “The Starkville Blues”—either bid farewell to an unwelcoming locale or warn against dangers lurking for those daring to visit said destinations. The fourth song does away with a specific name but is similarly dire in its dirge-like quality and unforgiving assessment of “The Town Where I Live” in lyrics such as “…it all seems to take a lot more than it gives/they say you’re too young, they say you’re too old/the job’s just been filled or you’re moving too slow…” In this context it makes sense Shea would emerge from these tales with a rousing country stomper in “(You’re Gonna Miss Me) When I’m Gone” and would offer, in the penultimate number, an existential affirmation of simply rolling with the flow in the Jack Clement-penned Johnny Cash classic, “Guess Things Happen That Way,” arranged in subdued emulation of Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue,” with drummer Shawn Nourse delivering the trademark paradiddles through the number. The most moving of Shea’s songs sounds not a warning about troubles ahead but rather presents a cautionary tale about a real-life couple headed for trouble. The principals are gifted folk singers Mary McCaslin and the late Jim Ringer, who met on the circuit, married and produced one celebrated album, 1978’s The Bramble & The Rose, and subsequently “flamed out in distressingly public fashion,” as Jerome Clark observed in his review of The Town Where I Live, but not before producing music still spoken of in hushed terms in folk circles. Over a gently shuffling country rhythm, Shea, his voice resonant and strong, and Claire Holley, adding plaintive harmony support, unfold a sympathetic but clear-eyed narrative of the duo’s triumphs and impending tragedy: “Fortune smiled, the songs rang true/they traveled far, their legend grew/trouble came on a devil wind/caught the Angel Mary and the Rounder Jim/two voices singing, two hearts entwined/songs that grew from the true vine/they rode the hard road both end to end/the Angel Mary and the Rounder Jim…” The Town Where I Live suddenly is transformed into a folk morality play. All these places where trouble lurks, and finally two doomed souls enter, Angel Mary and Rounder Jim, fated to learn they can’t beat the land, much as the characters in Deliverance learned they couldn’t beat the river. David McGee

![The Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred of 2017 (Part 1) 22 Rick Shea - 'The Town Where I Live' [OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/OygkMYaYzOo/hqdefault.jpg)

‘The Town Where I Live,’ Rick Shea & The Losin’ End, from The Town Where I Live

***

12. ZRI, Schubert At The Red Hedgehog Tavern–C Major Quintet D 956 (ZRI Music) (Review by Robert Hugill) –ZRI (Zum roten Igel), named for the major concert venue in Vienna, have followed up their 2014 disc of Brahms (Brahms and the Gypsy: Clarinet Quintet op. 115) with a similar treatment of Schubert’s C Major Quintet D956. So we have Schubert’s quintet re-orchestrated for the ZRI line-up (Ben Harlan, clarinet/bass clarinet; Max Baillie, violin; Matthew Sharp, cello/baritone; Jon Banks, accordion; Iris Pissaride, santori) interspersed with traditional folk-melodies. It all sounds rather unlikely–why on earth would you need to re-orchestrate Schubert’s divine quintet, and what has it got to do with Hungarian gypsy tunes? Quite a lot, as it turns out. Complete review by Robert Hugill here…

–ZRI (Zum roten Igel), named for the major concert venue in Vienna, have followed up their 2014 disc of Brahms (Brahms and the Gypsy: Clarinet Quintet op. 115) with a similar treatment of Schubert’s C Major Quintet D956. So we have Schubert’s quintet re-orchestrated for the ZRI line-up (Ben Harlan, clarinet/bass clarinet; Max Baillie, violin; Matthew Sharp, cello/baritone; Jon Banks, accordion; Iris Pissaride, santori) interspersed with traditional folk-melodies. It all sounds rather unlikely–why on earth would you need to re-orchestrate Schubert’s divine quintet, and what has it got to do with Hungarian gypsy tunes? Quite a lot, as it turns out. Complete review by Robert Hugill here…

ZRI present Schubert’s String Quintet in C, reimagined to sound as radical as when it was first written. Bursting with gypsy and Hungarian themes, it is here rescored to include clarinet, santouri (cymbalom) and accordion and interleaved with traditional tunes. ZRI stands for ‘Zum Roten Igel,’ the name of the major concert venue in Vienna in Schubert’s time but also of the tavern just behind it where bands played and composers caroused into the night; at one point Schubert even lived next door. His fluid embrace of folk tradition in this much-loved work is brought out in this exciting version, reflecting the daring and profound qualities of the piece itself.

***

14. ISAMBARD JONES & HIS ORCHESTRA, We Used To Have An Empire Now We Have Diabetes

14. ISAMBARD JONES & HIS ORCHESTRA, We Used To Have An Empire Now We Have Diabetes

The most unlikely and in many ways the most compelling pop-rock album of the year comes out of the blue, and from England, via the genius of rock journalist legend John Mendelssohn, who wrote the songs, plays most of the instruments and painstakingly produced Mr. Isambard Jones, whose tuneful voice is a cross between young David Bowie and that of a Jewish cantor, with a touch of Anthony Newley’s theatricality and the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band’s sense of the absurd in the mix. Producing Mr. Jones is a task unto itself, as he remains hindered by the effects of a stroke suffered a few years back and must record his vocals piecemeal, phrase by phrase, or word by word. You’ve heard of vocal “fixes”? In which artists re-record a word or phrase over one they’ve botched? Well, every word or phrase Mr. Jones sings is essentially a vocal “fix.” Amazingly, the listener would never know, as the performances are seamless, assured, wry, unself-conscious and at times touching.

Let us stop for a moment and consider Mr. Mendelssohn’s own description of this project: “Isambard Jones, a one-eyed Victorian purveyor of wry, tuneful, topical pop/rock music since 2017, was born in Bangalore in 1879, and then again a year later in Singapore, where his father was a diplomat and alcoholic. Young Is, the third-person singular present indicative version of the verb To Be, and short for Isambard, caught his first glimpse of England at 11, and almost immediately became an implacable seducer of kitchen staff. He later failed to date Joanne Lumley, and has resided since the early 1950s in a storage locker in Battersea Power Station. His hobbies are cricket, praying mantis, and locust, and he is available for lunches with the press if the press pays. His Orchestra comprises Darryll du Toit, at one time the Keith Richards of Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, and later ‘the cute one’ in southwest London’s Freudian Sluts. The Orchestra is conducted, and all its material written, by John Mendelssohn, who is mentioned in all your better David Bowie biographies, and many of the worse ones. A one-time rock journalist of international disrepute, he has been described on Rock NYC, an American music Website of incalculable influence, as ‘one of our more unique pop personalities, and like no one you have ever heard. From hard jingle jangles to experimental symphonic pop, his taste roams the landscape.’”

But you don’t make the Elite Half Hundred simply by making a wrong turn at Victoria Station. As the one critic who dared stand up to the criminal enterprise known as Led Zeppelin and properly trash the lumbering quartet’s first two albums (engendering a volume of hate mail possibly still ranking as a Rolling Stone record), conceding only that Jimmy Page “is the heaviest white blues guitarist between 5’4” and 5’8,” and an indefatigable promoter of his band Christopher Milk (in the pages of Rolling Stone, no less, a feat now, and for years, unimaginable in those pages), Mendelssohn’s own music has always shown his love and affinity for early British Invasion rock styles, with his lyrics evincing a more satirical bent but not at the expense of heartfelt sentiments and indelible images—think Tom Lehrer filtered through Ray Davies. Mendelssohn’s lyrical strengths remain in force on Mr. Jones’s debut; but though there are hints of the more raucous Mendelssohn in his keyboard work (the juxtaposition of gentle chimes with a twisted, processed keyboard solo in “A Beautiful Sight to Behold” will make you sit up and take notice), the overall feel of the project is more indebted to the British music hall style with a dash of Spike Jones for good measure.

‘When Handsome Johnny Sails Away,’ Isambard Jones & His Orchestra, from We Used To Have An Empire Now We Have Diabetes

We find for instance, a restrained but rather savage kissoff in “From Atop the Shard,” in which Mr. Jones warbles, “you’ve been kidnapped by savage Mongol hordes/they’re scarce of course in Norway/but I can always hope/one like you will hang herself if given enough rope…” In “When Handsome Johnny Sails Away” we encounter a percolating modern-day take on Ricky Nelson’s “Traveling Man” in the form of an ode to the girls (or, in one memorable lyric, a ladyboy) awaiting our hero in various ports and towns the world over. Sample lyric: “My fraulein down in Dusseldorf’s a hundred percent Aryan/she raises birds of prey for fun/’tho all they eat is carrion…” Had the Beatles ever gone Celtic, they might sound like what Messrs. Mendelssohn and Jones conjure on the lament “You Just Phone It In.” Listeners not too jaded to appreciate genuine affection should be moved by the tenderness in Mr. Jones’s voice when he sings, in “A Beautiful Sight to Behold,” “what I’d most like to see/is you in bed next to me/that, I tell you, would be a beautiful sight to behold”—the pause for “I tell you” is a heart tugging literary touch of the first order. “I Shall Not Sink,” the bubbling arrangement of which bears a passing resemblance to the Pogues’ “Dirty Old Town” done at a slower tempo, is a catchy ditty of self-affirmation with an impossibly lush chorus announcing, “Though I can’t pretend I won’t lapse/I intend to be the last reprobate standing/I won’t inject, nor will I drink, I shall not sink!” As anyone who reads Mr. Mendelssohn’s Facebook postings knows, he’s on top of the day’s pressing issues (and a most vocal critic of the VSG [Very Stable Genius] masquerading as President of the United States). He does not disappoint in that regard, providing Mr. Jones with the topical “The Lowly Cockroach,” therein observing, in part: “we scorn the lowly cockroach/who lives as God intended/our good luck will soon run out/our lease won’t be extended/the ocean’s full of toxic waste, the forests are denuded/if we imagine nothing’s wrong/we’re fatally deluded/we scorn the lowly cockroach/who lives as God intended…

Other joys abound on We Used To Have An Empire, Now We Have Diabetes, including a couple of tunes carrying parental warnings. All evidence indicates Mr. Mendelssohn is a prolific writer of prose and songs and will continue to be heard from in various guises (his blog Mendel Illness is must reading), but what the future holds for Isambard Jones is less clear. Having made a most favorable first impression with this collaboration, however, these two artists merit another go-‘round. David McGee

***

15. CHRIS THILE, YO-YO MA, EDGAR MEYER, Bach Trios (Nonesuch)

An album that elicits a considerable amount of excitement, the new Bach Trios album with Yo-Yo Ma, Chris Thile and Edgar Meyer is an instant classic and a must listen.

Bach albums are a dime-a-dozen. Articles about Bach albums that begin with statements referencing the vast volume of Bach albums in the world are also a dime-a-dozen. Less common, though, is a Bach album like this.

Cellist Yo-Yo Ma, mandolinist (and MacArthur Genius Grant winner) Chris Thile, and bassist (and fellow Genius Grant winner) Edgar Meyer have played together for decades, each known for their superlative talent and wide-ranging musical interests. What makes this new Bach album unique is that it, like them, is infused with a healthy dose of non-classical pedigree. … Complete review here…

***

16. MICHELLE DAVID, The Gospel Sessions Vol. 2 (Excelsior Recordings)

16. MICHELLE DAVID, The Gospel Sessions Vol. 2 (Excelsior Recordings)

Ironically, Michelle David’s The Gospel Sessions Volume 2 has such deep roots in Americana music that it probably would never be released by a U.S.-based gospel label. The current clamor for big and bold gospel singing and stadium-sized musicianship has eclipsed the more subtle, but no less soulful, sacred sounds and nuanced artistry of singers like Liz Vice and, as she demonstrates on this album.

‘Carry On,’ Michelle David, from The Gospel Sessions Vol. 2

David, born and educated in New York and living in Holland since 1994, reunites with multi-instrumentalists Onno Smit, Toon Oomen, and Paul Willemsen to offer a follow-up to her well-received first volume of The Gospel Sessions. This second iteration feels like an informal jam session among friends experimenting with new ways to deliver timeless messages. Complete review by Bob Marovich here…

***

17. STEVE GULLEY & NEW PINNACLE, Time Won’t Wait (Rural Rhythm)

In the bluegrass world Steve Gulley and Blue Highway’s Tim Stafford comprise one of the great contemporary songwriting teams. Small wonder, then, that Time Won’t Wait is so memorable, blessed as it is with four exquisite Gulley-Stafford tunes, and a Gulley solo copyright on the mountain-flavored “You’ll Cry For Me,” an unsparing kissoff directed at a feckless paramour, with Gulley’s harsh vocal supported by equally accusative support from Matt Cruby on banjo and special guest Tim Crouch howling on fiddle. In fact, a good deal of uncoupling occurs on Time Won’t Wait, ranging from Jim & Jesse’s resigned acceptance of fate in the fiddle-fired “Congratulations, Anyway,” to a Gullley-Stafford gem, “Leaving Sounds Pretty Good to Me,” a steady, midtempo workout with Gulley matter-of-factly (and with detectable jubilation) bidding adios and good riddance as Crouch, Cruby and mandolinist Gary Robinson Jr. provide a heated backdrop to a relationship’s closing ceremonies. Gulley reserves his deepest, most affecting vocal for a healing moment provided by the mountain gospel song of salvation, “Safe In His Arms,” with Crouch’s multitracked fiddle and the band’s close harmonizing burnishing the reverent vocal with plaintive outpourings. The close-miked sonics make the entire endeavor sound like diary entries. David McGee

‘Time Won’t Wait,’ Steve Gulley and New Pinnacle, title track from the new album.

***

18. CORKY SIEGEL’S CHAMBER BLUES, Different Voices (Dawnserly Records)

As if emphasizing that he isn’t the first composer to advance a blues-classical fusion, Chicago blues harmonica master Corky Siegel begins “Missing Persons Blues, Op. 26,” the first work on Different Voices, with an opening measure on harmonica echoing the iconic clarinet glissando heralding the start of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” The tune doesn’t unfold with the orchestral grandeur of Gershwin’s masterpiece, but over the course of its four minutes-plus running time it does achieve a textbook meshing of blues and classical elements, from the languid, moaning, New Orleans-textures Siegal crafts on harmonica to the cool swagger Ernie Watts brings on sax, while the West End String Quartet, working here in its guise as Siegel’s Chamber Blues String Quartet, injects rather Stravinsky-ish retorts in motivic development with a blues edge.

‘Missing Persons Blues, Op. 26,’ Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues with Ernie Watts, from Different Voices

Rather than Stravinsky, though, the apt touchstone for Siegel’s work is Antonin Dvorák, specifically his Symphony no. 9 (“From the New World”), of which Dvorák, newly infatuated with the roots of American music, said: “It is the spirit of the Negro…melodies which I have endeavored to reproduce in my new symphony.” Complete review here…

***

19. DAVID WOOD, Reflecting (olddavy records)

As summer waned, a new instrumental album from guitarist David Wood heralded the looming autumn season with beauty, serenity and invigorated spirit. Reckoning is a single composition with a running time of 34:39; if it had a subtitle, it would have to be Suite for Mind, Body & Solo Guitar. I don’t want to get too out there, but the nuanced moods here capture in music the turning of the earth, when “summer has o’er brimm’d their clammy cells,” as sensitively as Keats did in his enduring “To Autumn.” For fans of solo acoustic guitar, Reckoning is as fine a representative of the sub-genre as any other released in 2017.

Reckoning, the album, is an all-instrumental project devoted to a single like-titled composition with a running time of 34:39. Its cover depicts an old barn set in fading green, hilly country, situated on the banks of a placid river. The painting reflects much of the music in its serenity, but Mr. Wood, respecting nature’s unpredictability, offers textures of life beyond the laid-back scene on his album cover. At 11:30 or thereabouts, a series of rapid arpeggios brings sudden tension to the atmosphere, until the storm recedes, leaving behind a gentle, fresh breeze wafting restoratively over the landscape. As the composition unfolds, it turns ever more inward, reflecting, if you will, life both interior and exterior—a happy passage here, a somber one there, leading to a poignant, evocative benediction, and a tender “amen,” spare and touching, as life goes on, and the river keeps on flowing.

Reflecting follows Mr. Wood’s beautiful Christmas album of last year, A Christmas Gift (a former Deep Roots Album of the Week selection), which followed Dreaming, his first solo release, by 13 years. Although he made his professional bones as a touring musician for 20 years, playing pedal steel with major country artists (including Joe Diffie, Lorrie Morgan and Doug Stone), Mr. Wood studied classical guitar at the North Carolina School of the Arts (1973-1977). Much like A Christmas Gift, Reckoning promises to be one of those albums you’ll cue up year after year because it so perfectly fits the mood of a certain time and a certain place as the earth turns. David McGee

***

20. THE GRASCALS, Before Breakfast (Mountain Home Music Company)

It’s hard not to notice, and to point out, how the cover shot of the Grascals’ fine new album, Before Breakfast, pictures the six group members gathered around a table on which sits seven coffee cups. If the listener is the missing person, then it’s time to show up for a stellar outing by one of the finest contemporary bluegrass bands delivering one of its finest of many outstanding long players. Newest Grascal John Bryan, appearing on his second album with the band, makes a powerful impact with the high, keening urgency of his vocal take on the mountain gospel gem “I’ve Been Redeemed,” which itself is further redeemed by deeply felt soloing courtesy fiddler Adam Haynes and banjoist Kristin Scott Benson. In “Demons,” a Bill Anderson-Jon Randall co-write, founding member Terry Eldredge gives a chilling performance as a man addicted to the memories haunting him—“what I want ain’t what I need”—until he realizes “maybe I’m afraid of being free” and seems resigned to his fate. On the other hand, Eldredge has the album’s humor highlights in immersing himself in the frivolity of “Beer Run” (by Harley Allan and Robert Ellis Orrall). On the heartbreak side, the band brings it all together on a close-harmonized rendition of the classic “Pathway to Teardrops,” penned jointly by Wayne Walker, Webb Pierce and June Hazlewood and oft-covered over the years but never better than by the Osborne Brothers. Eldredge, Bryan and bassist Terry Smith will bring you to your knees with the sheer emotion and soulful ache fueling their harmonizing as they bring it home at the end with a stunning homage to the Osborne’s upper-atmosphere closing salvo, but the restrained, atmospheric support they’re given throughout by Benson and Haynes is a headline story as well. The “wow!” factor here is off the charts. The Grascals just keep getting better. David McGee

‘Delia,’ The Grascals, from Before Breakfast

***

21. JULIANA HALL (COMPOSER) WITH DARRYL TAYLOR (COUNTERTENOR), SUSAN NARUCKI (SOPRANO) AND DONALD BERMAN (PIANO), Love’s Signature Songs For Countertenor & Soprano Based On Shakespeare (MSR Classics) Review by Joseph Newsome.

Had he endured it, Thomas Paine would surely have agreed that 2016 was a year to try men’s souls. Whether troubled by matters global or personal, by politics or unspoken perfidies, by losses widely mourned or unnoticed, few sensitive spirits were untouched by the year’s tribulations. It was a year in which Shakespeare’s likening in The Merchant of Venice of a lone candle blazing in the night to the gleam of a good deed in a naughty world shone with its own illuminating truth. In the same scene in The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare wrote of the man affected by life’s vices that “music for the time doth change his nature.” The first quarter of 2017 has introduced new challenges and realities almost too fantastic to be believed—and, with them, pitifully little of the common sense that Thomas Paine identified as the hallmark of an enlightened free society. The power of music to change the natures of oppressor and oppressed is now more critical than ever before, the universal language of song needed to close the ever-widening gaps among neighbors and nations. When joining words with music, gifted American composer Juliana Hall perhaps does not consciously set out to create songs that close the circuits via which emotional currents flow from the individual to the universal, but the three song cycles recorded for MSR Classics’ new disc Love’s Signature reveal her extraordinary talent for crafting music that translates the meanings of texts into sounds that can be felt as well as heard. Whether handling the words of William Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson, or Marianne Moore, Hall exhibits an uncanny faculty for amplifying the innate musicality of poets’ diction. Placed by MSR Classics’ engineering within an aural ambiance that recalls a small recital hall, the sound both intimate and ideally spacious, the performances that inscribe Love’s Signature upon the listener’s conscience restore faith in music’s still-potent force for positive change even in troubling times. Complete review by Joseph Newsome here…

Syllables of Velvet, Sentences of Plush—7 Songs for Soprano and Piano on Letters of Emily Dickinson: IV. To Samuel Bowles The Younger. Juliana Hall, Susan Narucki, Donald Berman, from Love’s Signature: Songs for Countertenor and Soprano by Juliana Hall.

***

22. CAROL ROBBINS, Taylor Street (Jazzcats)

22. CAROL ROBBINS, Taylor Street (Jazzcats)

With Taylor Street (the title refers to the street in Chicago’s Little Italy neighborhood where her mother was born and raised), Carol Robbins asserts the jazz harp as a versatile ensemble instrument in the variety of styles her nine original compositions reflect. Now five albums into a lauded career (her previous long player was the acclaimed Moraga, released in 2012), Ms. Robbins has carried the jazz harp torch forward from her days as a student of the godmother of all jazz harpists, the late, great Dorothy Ashby. Just as Ms. Ashby in the 1950s, both established the jazz harp as a legitimate improvisational instrument, at a time when it was considered merely as a novelty backdrop, and featured it in varied contexts over the course of her 10 solo albums, so has Ms. Robbins taken Ms. Ashby’s cue and emphasized the instrument’s versatility and distinctive voices in fashioning a growing, and formidable, catalogue featuring jazz harp in both lead and supporting roles.

‘Full Circle,’ Carol Ribbons (jazz harp) with the Jazz Chamber Ensemble (Billy Childs, piano-Fender Rhodes; Larry Koonse, guitar; Bob Sheppard, sax/clarinet; Gary Novak, drums; Darek Oles, bass; Curtis Taylor, trumpet), from Taylor Street

Taylor Street is a slight departure from Ms. Robbins’s previous albums in focusing less on jazz harp solos and almost completely on her instrument in conversation with the Jazz Chamber Ensemble led by Billy Childs on piano and Fender Rhodes, and including Ms. Robbins, guitarist Larry Koonse, and sax/clarinetist Bob Sheppard. A solid rhythm section features drummer Gary Novak, acoustic bassist Darek Oles and electric bassist Ben Shepherd, Curtis Taylor rounds out the lineup on trumpet. The Robbins compositions give all the players ample room to shine in solo spotlights, and their collective effort reveals not only the Dorothy Ashby influence but also the groundbreaking jazz harp work of Alice Coltrane and the compositional daring of progressive British harpist David Snell, whose iconic tune “International Flight” seems to have made a big impression on Carol Robbins. Complete review here…

***

23. RAFIKI JAZZ, Har Dam Sahara (Riverboat)

Rafiki Jazz, which began as a collaboration between local musicians and migrant and refugee artists, creates mesmeric music that resonates deep, bound through with the rich color tones of the ancient musical heritages they explore. United in their mission to create a sound that crosses cultural boundaries, the music melds traditional vernaculars anew and expresses the power and beauty of difference. With its members hailing from six countries on four different continents the octet seamlessly combines the sounds of some of the world’s most distinctive folk instruments including the West African kora, Caribbean steelpan, Indian tabla, Brazilian berimbau and Arabic ney and oud along with inspirational vocals from the Sufi soul singer Sarah Yaseen and Hebrew and Hindi vocalist Avital Raz. Complete review here

‘Har Chand Sahara,’ Rafiki Jazz, from Har Dam Sahara

***

24. BOBBY OSBORNE, Original (Compass Records) (July)

24. BOBBY OSBORNE, Original (Compass Records) (July)

Back in 2013, while producing Peter Rowan’s acclaimed The Old School album (reviewed here in Deep Roots and also coming in at #47 on the 2013 Elite Half-Hundred), Compass Records founder/banjo virtuoso Alison Brown heard then-81-year-old bluegrass giant Bobby Osborne comment on how he was unlikely ever to record another solo album. Having seen in the sessions how much more Bobby had to give musically, Ms. Brown made a priority of proving him wrong on that point. The result, Original, is a triumph of the first order. Complete review here…

‘I’ve Got to Get a Message to You,’ a bluegrass treatment of the Bee Gees’ 1968 hit, Bobby Osborne, from Original

***

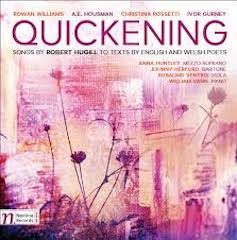

25. QUICKENING: SONGS BY ROBERT HUGILL to Texts by English and Welsh Poets (Navona Records)

A regular classical contributor to Deep Roots since December 2013, Robert Hugill’s many hats—journalist, blogger, lecturer– include that of the composer. His catalogue includes the opera The Genesis of Frankenstein, and the motet Dominus illuminatio mea, and, as of 2017, a new crowd-funded disc of art songs, Quickening, his settings of texts by the poets Ivor Gurney, Christina Rosetti (who gave us, among others, the seasonal evergreen “In the Bleak Midwinter” and is here represented by six poems comprising the title cycle) and A.E. Housman; the album opens with settings of three texts (Morning, Afternoon, Evening)–best known as “Winterreise: for Gillian Rose 9 December 1995,” here identified as “Winter Journey”–by Dr. Rowan Williams, 104th Archbishop of Canterbury, and performed with nuanced emotion by baritone Johnny Herforrd accompanied by pianist William Vann. In addition to Messrs. Herford and Vann, mezzo-soprano Anna Huntley appears as does Rosalind Ventris on viola. This is not party music. It’s designed to be reflective, which is not to confused with “dark.” ”Sing no sad songs for me,” Ms. Huntley advises in the first Rosetti setting (“Song”), and though the Rosetti poems are somber, the lilt in the singer’s voice lends a sense of hope to the “Quickening” texts. Hugill’s settings of the A.E. Housman texts prove a story unto themselves. In Housman’s time same sex relationships were not simply frowned upon, they were illegal. The poet was deeply in love with his Oxford roommate, Moses Jackson, but it was to be an unrequited love affair. Three of the four Housman texts (“He Looked at Me,” “He Would Not Stay for Me,” “Because I Liked You Better”) are in keeping with their author’s emotionally withdrawn nature but not at the expense of obscuring his yearning for Jackson. A fourth Housman text, “A.J.J. (When He’s Returned),” mourning the death of Jackson’s brother, Adalbert, who roomed with Housman and Jackson at Oxford, is a moment of austere beauty and poignancy, as Vann’s minimal piano accompaniment sets Herford’s moving performance—at times the listener can sense tears welling up in the singer’s eyes—in bold relief. Think of Quickening as being perfect for those moments in a day when you need to take a breath from the usual rigors and perhaps take a moment for personal inventory. It really grows on you. Quickening is available at Amazon. David McGee

‘Quickening: No. 4, Remember,’ Anna Huntley (vocal), Rosalind Ventros (viola), from Quickening: Songs by Robert Hugill to Texts by English and Welsh Poets

Click here to go to The Elite Half-Hundred of 2017 (Part 2)

Click here to go to the Deep Roots Albums of the Year (2017)