en CASA LIMON, David Broza (S Curve Records)— David Broza’s declaration that the internationalism of humanity lies in music–no matter the extent of numerous Diasporas across the universe–has never been in any doubt. We have had two examples of this not long ago: the first was the 2016 documentary East Jerusalem | West Jerusalem and the album Andalusian Love Song. However, this artistic thesis has never been more powerfully stated or–more exactly “sung”–than on en Casa Limón, a brilliantly conceived and [perhaps even more brilliantly] executed by the prominent and seemingly ubiquitous Javier Limón, himself a guitarist, but even better-known for his association with the legendary flamenco musician from Andalucía, Paco de Lucía.

en CASA LIMON, David Broza (S Curve Records)— David Broza’s declaration that the internationalism of humanity lies in music–no matter the extent of numerous Diasporas across the universe–has never been in any doubt. We have had two examples of this not long ago: the first was the 2016 documentary East Jerusalem | West Jerusalem and the album Andalusian Love Song. However, this artistic thesis has never been more powerfully stated or–more exactly “sung”–than on en Casa Limón, a brilliantly conceived and [perhaps even more brilliantly] executed by the prominent and seemingly ubiquitous Javier Limón, himself a guitarist, but even better-known for his association with the legendary flamenco musician from Andalucía, Paco de Lucía.

More than anything else, the surprise of listening to a recording where he doesn’t sing a word of the lyric is quite extraordinary. Perhaps more extraordinary for many will be discovering just what an extraordinary guitarist Mr. Broza actually is, as well as the fact that he is also a superb songwriter. He proves this song after song on this disc. The latter ought hardly to be in dispute as Mr Broza has several albums to his name; each of which strengthens his reputation. Somehow, however, this instrumental performance comes with its own rather attractive musical “nudity”–and not simply of body [so to speak] but of soul and spirit as well. This, too was not in doubt. But the eloquent power of this music is rather overwhelming.

Most striking throughout this repertoire is that Mr. Broza’s humanity permeates the depth of this music and the guitar[s] on which it is played becoming, as the album progresses, a supreme means of Romantic self-expression. But whereas many of his contemporaries might [and do] use the instrument to create heroic portraits and vast panoramas, Mr. Broza is an introvert and miniaturist, infusing the conventional song-form with an intimacy and an emotional intensity which can only be described as the poetry of feeling. Mr. Broza is also a sublime technician and in his hands the guitar–with such techniques as “nut-side”, “nail-sizzle” and other percussion effects–becomes a veritable orchestra.

Follow this link to the full review by Raul da Gama in World Music Report.

‘Autumn Longing,’ David Broza, from en Casa Limon

***

NO RISK NO REWARD, Isaac Carree (Shanachie Entertainment Group)– Isaac Carree has bestowed upon his first solo album in seven years a very accurate title. And in so doing, he has scored his best solo recording to date. No Risk No Reward finds Carree, former member of the genre-bending Men of Standard, pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a gospel album. In fact, the CD is two albums in one. The first part comprises an extended quiet storm expression of love to Carree’s earthly love, wife Dietra. As with Kim Burrell’s 2011 The Love Album and Fred Hammond’s 2012 Love, God, and Romance, Carree’s love songs—the majority written by one of the album’s producers Elvis Williams (aka Blac Elvis)—are infused with cozy Christian spirituality.

In “Love Affair,” Carree defines the ultimate love triangle as “you, God and me.” He admits dodging a relationship bullet in “Amen,” which features Mr. TalkBox. “It was supposed to be like heaven,” he sings, “but I put you through hell.” On the countrified ballad, “Woman First,” Carree fronts Tim McGraw’s band to acknowledge the many ways his wife makes life wonderful. The current single, “HER,” is a dedication to Deitra specifically and women generally. Loving her, Carree sings to God, is “thanking you.” … Follow this link to the full review by Bob Marovich in Deep Roots

‘Woman First,’ Isaac Carree, backed by Tim McGraw’s band, from No Risk No Reward

***

TOTAL FREEDOM, Kathleen Edwards (Dualtone Records)– Even after the opening few seconds of Total Freedom it is immediately obvious that Kathleen Edwards knows what she is doing. Album opener “Glenfern” grabs your attention and keeps it, and the rest of the record follows suit. Straight off the bat, it is clear that this is an easily accessible, good record.

But, whilst first impressions are undoubtedly important, the true brilliance of this album comes once you have a deeper understanding of it. Scratch the surface of the catchy hooks and driving rhythms and you discover a softer, vulnerable underbelly. Seeds of lyrics about the most mundane of topics (birds on a feeder, the online street view of an old house) grow into living, breathing stories. And like the best short stories, Edward’s lyrics show you a glimpse of real lives; a vignette of a memory, the middle of the tale, and leave so much to the imagination—what else is going on in this person’s world?

That, in a nutshell, is the brilliance of Total Freedom–every day ordinariness extrapolated to its most beautiful, ethereal state. And to those who know Edwards’ story that will not come as a surprise. That’s because Edwards quit music in 2014. She quit so emphatically, in fact, that she opened a coffee shop and called it Quitters. It is clear from Total Freedom that, in her own words, the best thing Edwards ever did was quit. …

Follow this link to the full review by James Beck in Thank Folk For That

‘Hard on Everyone,’ Kathleen Edwards, from Total Freedom

***

CELEBRATING FISK! (THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY ALBUM), Fisk Jubilee Singers, Musical Director: Dr. Paul Kwami (Curb Records)– The Jubilee Singers’ mission, if you will, has remained intact for a century and a half. During its legendary breakthrough years at the turn of the 20th Century, the group was a male quartet led by the brilliant John Work II, who sang 1st tenor, with James Andrews singing 2nd tenor, Alfred Garfield King singing 1st bass and Noah Walker Ryder as 2nd bass. While on a northern tour in 1908, this iteration of the Jubilee Singers made the group’s first recordings, for Victor. From that point through1927, the group and its ever-changing lineup of student-singers recorded steadily, bringing the African-American spiritual legacy out of the shadows of slavery, at once laying the groundwork for modern gospel and shaping the soundtrack for the Civil Rights Movement. In 1997 Document Records issued three essential CDs documenting the Jubilee Singers’ groundbreaking years, from 1909-1927, with Volume 3 (1924-1940) also featuring 15 transcriptions of the group performing live in 1940 on Nashville superstation WSM, home of the Grand Ole Opry. But the Singers carried on through the decades, occasionally making stops in a recording studio. By 2003, the male quartet heard on the first recordings with John Work II had grown into an 18-member mixed gender vocal ensemble under the direction of Paul T. Kwami on the Grammy-nominated album, In Bright Mansions.

What better way, then, to honor the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ impending (in 2021) 150th anniversary, then, than to assemble the current members in Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, legendary home of the Opry, to reprise in the here and now a few of the great moments of the past century and a half along with contemporary spiritual and inspirational fare. In a bit of exquisite cultural timing that is part and parcel of the Jubilee Singers’ storied history, some special guests join in to add an inclusive element to the proceedings: From being ‘buked and scorned by Whites at the outset of their journey, their numbers on this project include White artists. Shed all this history, however, and still, what you have in Celebrating Fisk! Is one of the most essential albums of this or any other year—but especially of this year, for all the obvious reasons. Follow this link to the full review by David McGee in Deep Roots.

‘Wade in the Water,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from Celebrating Fisk! The 150th Anniversary Album

***

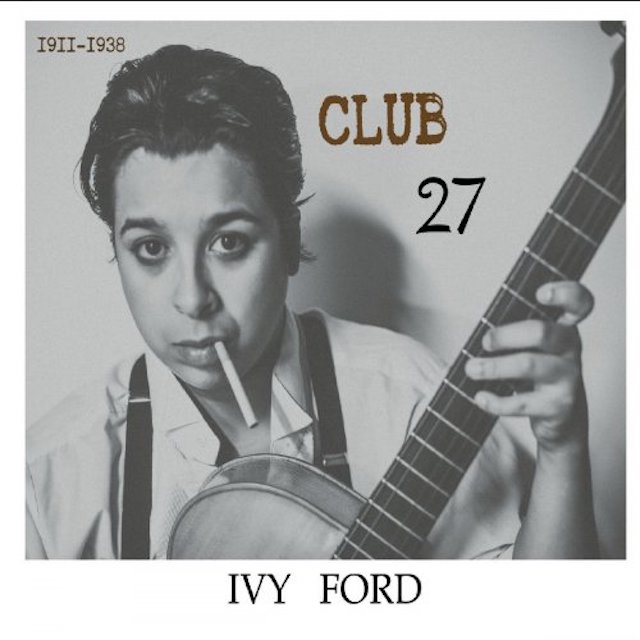

CLUB 27, Ivy Ford (Ivy Ford Music)– On her startling 2019 album, Harvesting My Roots (ranked #27 on the Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred of 2019), the rising Chicago blues star Ivy Ford (native of Waukegan, IL) observes “there is no precious time to waste.” These words animate her original slow blues, “Daddy of Mine,” in which, to the accompaniment of her own, spare, haunting piano and plaintive, open-hearted vocal, she forgives her father his shortcomings and embraces him anew. On the topic of no precious time to waste, her new album, Club 27, hammers that sentiment home in a way both personal and sociological: personal in the sense that having recently turned 27 herself, she’s keenly aware of the eerie benchmark age 27 has been in the music world, which takes us to the sociological in that Robert Johnson, Amy Winehouse, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Kurt Cobain are all united in the club of artists who perished in their 27th year. On Club 27, in crafting her version of the dense, turbid miasma in which Kurt Cobain set some of his most unsettling scenes, Ford seems to speak for all of these fallen icons in her song “Fine” when she howls sans mercy, “I may look like I’m alright/but I’m broken, I’m not fine/why don’t you look at me/how come you didn’t see…” Harvesting My Roots was in many ways Ms. Ford coming to grips with family and individual history; Club 27, sounding like the next chapter of her reclaiming her own time, asks us to see beyond the image into the human heart and not shy away when it cries out for help in song (“Help,” in fact, was written in by then-25-year-old John Lennon, who pleaded, “Help me get my feet back on the ground/won’t you please, please help me!” Given that the Beatles ruled the world at the time—1965—and their world must have been perfect, how many of us heard the song as anything more than an expression of fleeting discomfort? Words flow out like endless rain into a paper cup, you might say, and tumble blindly as they make their way across the universe.)

Ivy Ford says Club 27 “comes from a place of necessity.” She released it on her own 27th birthday, both to pay tribute to the timeless work created by gifted artists shadowed by impending tragedy in their youth, and to announce her own intention to decline membership in their exclusive domain. She doesn’t cover their songs; hers are all originals, some evoking the styles of the artists we lost too soon, some grooving to her own sense of style in mastering roots genres across the board. She plays a mean guitar, as she’s proven on two self-released studio albums (Harvesting My Roots and her debut, Time to Shine) and on a live album from 2018, Live at Mickey Finn’s Brewery, which also reveals her to be an engaging stage presence. She’s been playing professionally since age 13 and is skilled on multiple instruments in addition to her polka-dot “Buddy Guy” Stratocaster—piano, organ, alto sax, drums, bass—an autodidact all the way. She really began to make her move in 2014, when blues fans around Chicago, her new home base, took notice of Ivy Ford and The Cadillacs in the local clubs; in 2015 she opened for Buddy Guy at his Chicago club, then began sharing bookings with most of the Windy City blues stalwarts while building her own fan base. A colorful personality and a bit of a fashion diva with a sense of humor, she’s nevertheless about substance over style—you can’t fake the earthiness, the soulfulness, the veracity of her sturdy voice; the plainspoken eloquence of her lyrics; or the authority and inventiveness of her instrumental work. In short, Ivy Ford is the real deal, and Club 27 a major statement of an artist coming fully into her own. Most assuredly, attention must be paid. Follow this link to the full review by David McGee in Deep Roots.

‘Fine,’ Ivy Ford, from Club 27

***

THE UNENDING ALTERATION OF THE HUMAN HEART, Gabrielle Louise (www.gabriellelouise.com)– “There’s an awful lot of words to wade through/I know that neither of us know the way/you don’t want to hear about the ways I blame you/don’t want to hear a single thing you say/ooooh, how did we run aground/once there was so much water, we drowned…”

So begins, over a soft, fingerpicked guitar introducing the song “Words,” Gabrielle Louise’s astonishing The Unending Alteration of the Human Heart, a quiet, piercing, masterful deconstruction of profound betrayal and the toll it takes—in this case the outcome is clearly announced in the album title. By removing the mystery of what is about to unfold in her songs, Ms. Louise clears the field for the listener to simply absorb the story. Perhaps a listener can find his or her own place in the perspectives she offers, but in the end that’s not the point of this endeavor. Listen, just listen, the songs seem to say, with its overriding message articulated succinctly in “House of Cards,” to wit: “’Til you’re honest with yourself you’ll break every heart.” Find yourself in these songs if you will, but she’s addressing herself in unvarnished interior monologues, leading by example in facing head-on hard truths about life, love and loss. …

The settings for these songs are spacious and languorous, evoking the landscape Ms. Louise knows well in her native Colorado and placing her stylistically in league with Ms. Cash and Ms. Speace, with equal elements of country and folk forming the soundscape for the singer’s crystalline vocals to shoot straight through the heart, never more so than when she soars into her dulcet upper register—it’s a thing of beauty, an instrument of deep passion and near-palpable spirituality. …

In the sanguine country strains of “See In The Dark,” snapshots of loving memories (“how easy I know you/know you by the shape of your hands…it’s easy to know you/know you by the sweet way you stand…”) evolve into a searing reality: “Time is a tyrant, taking all that is tender…” In fact, time looms over so many songs here, what it gave and, most critically, what it stole. In the song “Time,” she sings, “Life alone is simple/it’s not half as crazy/it’s just time…time… time…all there is is time…” in the midst of cataloguing all that’s gone away; time hangs on her soft, breathy vocal like an epic weight.

Follow this link to the full review, “Places in The Heart,’ by David McGee in Deep Roots

‘Time,’ Gabrielle Louise, from The Unending Alteration of the Human Heart. Filmed and edited by Being Films.

***

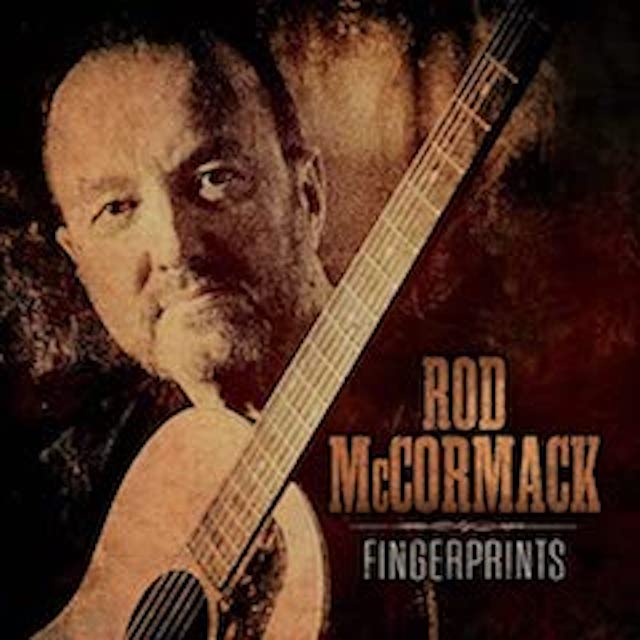

FINGERPRINTS, Rod McCormack (Sonic Timber)– Strangely, the pandemic has yet to produce much in the way of memorable music in response to the crisis. But now and again someone pops up with an album’s worth of songs conceived and recorded well ahead of COVID-19 that enters our daily conversation but which, by its perspective, seems informed by current events and consequently considers means of survival, paths forward or takes a hard left into matters of the heart seen in musical high relief.

The deepest, most moving entry in this abridged field to date comes by way of an Australian native who heretofore, for years, has made himself a first-call collaborator in this country and in his own by lending his songwriting his instrumental virtuosity in the studio and on the stage and his studio expertise as a producer to the efforts of a host of artists familiar on both shores, among these being kd lang, Kasey Chambers, Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, Paul Kelly and, tellingly, James Taylor. In his homeland, he’s served as musical director for Australian tours by the likes of Trisha Yearwood, Pam Tillis, Jo Dee Messina and others. Now, finally, we hear Rod McCormack’s own voice, singing his own songs, advancing his world view on his debut solo album, Fingerprints, a display of songcraft, musicianship, vocalizing and soulfulness of the highest order. Yet Fingerprints is not about or even inspired by the pandemic, but as a work of art it captures the mood of a changing world as surely and brilliantly as did his buddy James Taylor’s timeless, classic sophomore album, Sweet Baby James, in ushering in the more contemplative singer-songwriter era following the turbulent ‘60s. It’s a strictly personal viewpoint on my part, but I hear Fingerprints echoing the soothing, healing mood of Sweet Baby James and being equally as right for this moment as the latter was for its moment. Follow this link to the full review by David McGee in Deep Roots.

‘Wherever You Go,’ Rod McCormack with Claire Lynch, from Fingerprints

***

CABIN FEVER, John McCutcheon (www.folkmusic.com)– Back in mid-March, John McCutcheon found he wasn’t feeling tip-top. He was newly returned from an Australian tour and stepping into a burgeoning public health crisis in his native land. Being an informed citizen and aware of what was unfolding, he retreated to his North Georgia cabin to isolate as a means of protecting his wife and elderly mother-in-law. Over the course of the next three weeks, with not much else to do besides read, write and chat with friends, the prolific folk singer-songwriter produced 18 new songs. These superseded the 30-plus new songs he had written for an album he was planning to record with some high-profile roots stalwarts such as fiddler Stuart Duncan. “That pesky virus kind of put a kink in the notion of gathering a bunch of my pals and going into a windowless recording studio for days on end,” McCutcheon explained in a press release accompanying Cabin Fever. “I mean I love these folks, but…” …

Post-quarantine, McCutcheon returned home and to his home studio where, with only his voice, guitar and piano present, he recorded the newest tunes and then sent them to be mixed and mastered by the legendary Bob Dawson at Bias Studios in Springfield, VA. Voila! A new album emerged only a couple of months after the first new song for it had been completed. As McCutcheon has explained, the album is “not exclusively about COVID-19 and its effects, [but] came out of that milieu.” On those terms, it appears to be the most direct album-length response to the pandemic any artist produced in 2020, even if it engages the pandemic obliquely at times. It is also, as far as yours truly can tell, the only album of note to explicitly pay loving tribute to front line workers, whose trials and tribulations in caring for the sick and dying remain, alas, a headline story as this is written in January 2021. In “Front Line,” the album’s starting point, McCutcheon’s warm voice is strong and proud, his guitar accompaniment forceful and assertive, his lyrics empathetic and bold—“On the front line, there’s no place to go/facing the foe where it’s found/on the front line, there’s no time to be scared/pray you’re prepared and just stand your ground…”—in delivering a stirring homage to the bravest of the brave in this fight. But he also turns pandemic language on its ear to flesh out a fuller picture of our times. Though we are now well acquainted with the “shelter in place” directive, for instance, who among us thinks of it in terms of the perennially under siege homeless population? Fashioning a deliberately paced ambience on delicately fingerpicked and strummed passages, McCutcheon coolly speaks in the voice of a homeless man who is unruffled by—and invisible in the midst of–the events swirling around him: “I’m sheltered in place for years/nobody’s know that I’m here/I’m one of the many who just disappears/I’ve sheltered in place for years…” …

As for another aspect of our annus horribilis, McCutcheon pays tribute to the late John Prine, lost to COVID-19 last year, in a beautiful appraisal of the latter’s singular art, of songs “so complex in their simplicity, so honest and so true/just what every writer wished that they could do,” before ascending to a chorus guaranteed to produce a misty-eyed state in a listener engaged at all with Prine’s work, to wit: “There’s an angel from Montgomery that’s finally taken wing/and a place up there called Paradise/where even Sam Stone sings/all the losers, lovers, loners gather around the throne in a mighty choir/to welcome John Prine home…”

Follow this link to the full review, “Dispatches from Solitude,” by David McGee in Deep Roots

‘Front Line,’ John McCutcheon’s tribute to front line workers in the pandemic, from Cabin Fever

***

DOCKSIDE SAINTS, Cary Morin (Cary Morin LLC)– Anyone who’s been paying attention to Cary Morin’s art for the past few years should have seen Dockside Saints coming. Since first emerging best known as a gifted, unique guitarist, Crow tribal member Morin has gone on to make a series of albums—electric with a band and solo acoustic, notably on a trilogy of stunning albums culminating in 2017’s gem, Cradle to the Grave—that have elevated his songwriting to a position commensurate with his reputation as an instrumentalist. In the past three years since Cradle, he has not only refined his songwriting further and demonstrated how even the most gifted of instrumentalists always finds room for deeper, more meaningful expressiveness, but he’s also literally found his voice. That is to say, with every album he’s become a more nuanced vocalist while plumbing for deeper levels of feeling. Amazing as it may sound, this most personal and most self-aware of songwriters has continued to strip away any constraints or reservations he may have had about cutting too close to the bone for comfort in articulating everything from frank admissions of personal shortcomings to gratitude for the love blessing his life to an ever-heightened sense of spiritual guidance leading him to the next outpost on his artistic journey. On Dockside Saints, all the elements of this journey congeal, magnificently and powerfully, in service to a fully realized work of art. He’s on his own plane now. …

Elevating the phrase “kicking it up a notch” to absurd heights, Crow tribal member Cary Morin has delivered an album as stunning for its emotion-laden vocals as it is for the quality of the songwriting and guitar artistry. Herein the artist’s deeply personal investment in every facet of his music is bound to stir souls and bring some to their knees. In the bluesy mea culpa “Exception to the Rule,” he moans, “I know I’m not that easy to be around,” and if you close your eyes you would swear he’s channeling Gregg Allman from the afterlife, as the song’s thick, organ-enhanced groove serves to heighten the impact of what reveals itself as a powerful love song. Equally close to the bone, “Valley of the Chiefs” poetically addresses a true family tale of Morin’s grandmother being kidnapped by a neighboring tribe, set to an ominous shuffling backdrop of brush drums and Morin’s precision fingerpicking. Arguably—because cases could credibly be made for a couple of other instances—the most scintillating demonstration of his atmospheric fingerpicking rolls out in “Tonight,” a heady sonic collage of cannon-shot drumming propelling the action forward. As piano and organ riff in near-Impressionistic bursts around Morin’s cascading fingerpicked lines, the song unfolds to be kin to “Exception to the Rule” in the heartfelt musings of a man feeling unmoored, finding comfort in “going out on the river” where the water “turns incandescent” in the light and seems to buoy his resolve to “go back home tonight” where waits one who is “a muse to me/you help me break on through.” Really, no other artist writes love songs quite like Morin’s, in which the expressed passions are often inextricably linked to experiences in the natural world. Follow this link to the full review by David McGee in Deep Roots.

‘Exception to the Rule,’ Cary Morin, from Dockside Saints

***

THE OLD SIDE OF TOWN, Alicia Nugent (Hillbilly Goddess Music)– Following three acclaimed albums released between 2004 and 2009 and being anointed “The Hillbilly Goddess” in light of her throaty, backwoods cry being compared favorably to those of great country singers of yore, Alicia Nugent took a 10-year powder in order to attend to a variety of personal matters, including lost love, the passing of one of her daughter’s beloved friends and, not least of all, the death of her father. Now regrouped and returned to the studio, she’s enlisted a great producer in Keith Stegall and a lineup of stellar musicians (including Rob Ickes, Stuart Duncan, Brent Mason, Dan Dugmore, Tommy Hardin, Paul Franklin, et al.) to join her on nine songs, half of which she co-wrote, including one with the legendary Carl Jackson, “They Don’t Make ’em Like My Daddy Anymore,” a haunting, midtempo country ballad clearly born of personal tragedy. The short review of the results: She (and they) hit it out of the park.

Nine songs may seem a bit slight to many listeners, but Ms. Nugent says what she wanted to say and leaves it at that-nothing extraneous or superfluous to the soul searching at hand. Given the personal trials shadowing the performances here, the patina of sorrow overhanging the entire effort is as undeniable as it is piercing; but in the end, it’s all sweet sorrow, beautifully articulated by one of the purest, most affecting backwoods voices of her generation. Follow this link to the full review, “The Silence Lifts,” by David McGee in Deep Roots

They Don’t Make ‘Em Like My Daddy Anymore,’ Alicia Nugent, from The Old Side of Town