The Deep Roots Albums of the Year for 2018, numbering 10, reflect both a rich period of new roots music but also recognize a number of veteran artists having career years, you might say, along with some younger artists—very young in the case of Raven and Red (one of whose members is still in high school)—showing real promise for the long term. As usual, our honorees reflect our broad definition of roots music, ranging from sacred songs to folk to blues to bluegrass to Americana to classical. We also have a number of repeat winners in the 2018 list: Cary Morin makes his second consecutive appearance here; Michael Martin Murphy, Eric Bibb and the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Ephesus are now all three-time winners, and Rosanne Cash (shown above) is twice a winner. The only sadness this list brings us is in reporting the impending retirement of the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Ephesus as a recording entity: The Hearts of Jesus, Mary & Joseph marks the moment the Gower, Missouri-based order, having outgrown its current monastery, loses some of its membership to a new church the order is establishing to accommodate its burgeoning community. As assistant prioress Sister Scholastica says, “There is a time when the older children grow up and must begin their own families and carry on the family line.” Gone they may be, but the transcendent music the sisters made will live on, vital as ever. And as always, we sweeten the year-end mix with our Elite Half-Hundred of 2018, a selection of 50 albums that made the year all the more memorable and remain in heavy rotation in our house. Follow the links at the bottom of this page to Parts 1 and 2 of the fabulous fifty. –-David McGee

***

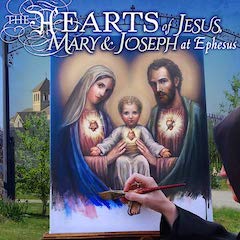

THE HEARTS OF JESUS, MARY AND JOSEPH AT EPHESUS, Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles (Benedictines of Mary)—This haunting new recording by the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles, a community based in rural Gower, Missouri, is every bit as humbling and awe inspiring as the nine albums preceding it, but alas, it arrives with a tinge of sadness—not in the songs, mind you, but in the fact of its being announced as the Benedictines’ final recording. The order, which had two members upon its founding in 1995, has now outgrown its monastery; it is currently at capacity at 35, with almost the same number in consideration for admission. Supporting itself with made-to-order vestments, greeting cards and CD sales, the order has raised $4 million towards the $6 million it needs to build a new priory church “where God wants us,” assistant prioress Sister Scholastica told Memphis-based photojournalist Karen Pulfer Focht. Sisters from the current monastery will go forth to establish the new church and thus signal the end of the singing nuns as currently constituted. “It would be nice to stay together,” Sister Scholastica added, “but it is very much like in family life: there is a time when the older children grow up, and must begin their own families and carry on the family line. … I can say it will be the most painful thing we have ever experienced as a community since we have such deep sisterly love for each other.”

THE HEARTS OF JESUS, MARY AND JOSEPH AT EPHESUS, Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles (Benedictines of Mary)—This haunting new recording by the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles, a community based in rural Gower, Missouri, is every bit as humbling and awe inspiring as the nine albums preceding it, but alas, it arrives with a tinge of sadness—not in the songs, mind you, but in the fact of its being announced as the Benedictines’ final recording. The order, which had two members upon its founding in 1995, has now outgrown its monastery; it is currently at capacity at 35, with almost the same number in consideration for admission. Supporting itself with made-to-order vestments, greeting cards and CD sales, the order has raised $4 million towards the $6 million it needs to build a new priory church “where God wants us,” assistant prioress Sister Scholastica told Memphis-based photojournalist Karen Pulfer Focht. Sisters from the current monastery will go forth to establish the new church and thus signal the end of the singing nuns as currently constituted. “It would be nice to stay together,” Sister Scholastica added, “but it is very much like in family life: there is a time when the older children grow up, and must begin their own families and carry on the family line. … I can say it will be the most painful thing we have ever experienced as a community since we have such deep sisterly love for each other.”

So no more Benedictines albums? “Recording again seems a great improbability since several sisters will be sent, but one never knows what God has up his sleeve!”

‘Hymn to the Three Hearts,’ an original hymn from The Hearts of Mary, Jesus & Joseph at Ephesus, with music by Linda Nardi, lyrics by the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles

With four #1 Billboard Classical albums and now three Deep Roots Albums of the Year awards on its shelf, the sisters exit by raising a reverent, bracing sound on The Heart of Mary, Jesus and Joseph at Ephesus, a collection of 22 songs (in Latin and English) dating from the Sacred Heart of Jesus devotions revealed to St. Margaret Mary Alacoque in the 1670s and ranging across the centuries in Hymns to the Immaculate Heart of Mary (notable among these being the complex, cascading harmonies of “The Sub Tutum” by the prolific French Baroque composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier) to Hymns to St. Joseph, including a new original piece in English, “Blessed Be St. Joseph,” a most soothing meditation. Notable among the new original songs is “Hymn to the Three Hearts,” the final, beautiful and aching track that serves as a comprehensive coda of the themes explored herein. Linda Nardi, a Long Island-based composer who wrote some of the music for Ken Burns’s National Parks documentary film, heard the sisters’ music on New York’s classical music radio station, WQXR, and reached out to the order with an offer to compose something especially for the Benedictines; the sisters then added lyrics to Ms. Nardi’s music.

‘Within Thy Sacred Heart,’ Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Ephesus, from The Hearts of Mary, Jesus & Joseph at Ephesus

If this indeed is the final testament from the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles, then rejoice in the purity of expression and depth of devotion they offer, and say an amen that they were ever among us.

Note: Proceeds from CD sales go towards the building fund. The Heart of Mary, Jesus and Joseph at Ephesus is available at Amazon, but buying direct from the sisters’ website ($15) means more of the full retail price goes directly to the order. –David McGee

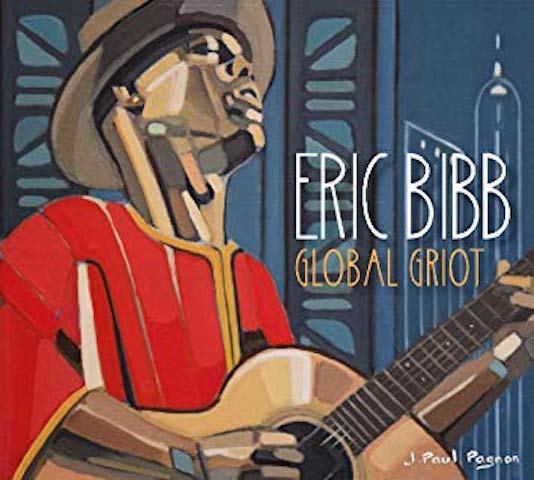

GLOBAL GRIOT, Eric Bibb (Stony Plain)– Exploring the themes of unity, inclusiveness and social justice from a spiritual perspective, Eric Bibb delivers a double-disc masterpiece in Global Griot, an album ideally suited to the temper of progressive times, or, as better phrased by Bibb, “challenging times.” Recorded in a dozen studios in lands far and near, Global Griot finds Bibb immersed in the West African tradition of history and storytelling while addressing issues relevant to all cultures. Singing with deep feeling, commitment and authority over mostly acoustic soundscapes occasionally fleshed out by horns, background singers (a Griot Choir on “Gathering of the Tribes,” for instance), koras, even pedal steel (on “Picture a New World”), Bibb takes the measure of the moment but always tempers harsh reality with optimism (the bluesy “Human River”). He allows himself a humorous, albeit scathing, assessment of the current occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in “What’s He Gonna Say Today” (“we’re talking pure madness here”) but most often yearns for the higher ground of spiritual enlightenment and connection for all humankind in prayerful, folkish missives such as the Jesse Winchester-like “Let God.” Bibb’s message? “Let the spirit give us wings.” Amen to that, brother. –-David McGee

Eric Bibb shares some ideas about the current occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in ‘What’s He Gonna Say Today,’ from Global Griot

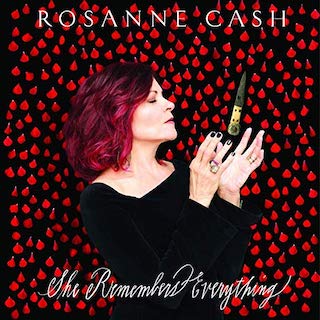

SHE REMEMBERS EVERYTHING, Rosanne Cash (Blue Note)— On the surface and on balance, it would appear Rosanne Cash has spent the better part of the past 12 years coming to terms with everyone but herself: 2006’s Black Cadillac was born in the wake of losing her mother (Vivian Liberto Cash Distin), her stepmother (June Carter Cash) and of course her legendary father, Johnny Cash. In 2009 she remembered her father’s gifts to her in The List, classic country songs culled from a list of 100 drawn up by her dad in Rosanne’s early years on the road with the Cash troupe, before she launched her influential solo career. In 2014 the pendulum began to swing back to her story, explicitly, in the haunting The River & The Thread, wherein the Memphis-born but California-raised Rosanne explored the southern landscape as she remembered it from her youth in songs by turns poignant and warm, with occasional flashes of humor, but always returning and turning to the inner light. During this time she also assumed stewardship of her father’s legacy, protecting it from outsiders that would try to co-opt it (memorably, when country gasbag John Rich told a rally crowd that if Johnny were alive he would vote for John McCain, it took Rosanne all but a few minutes to fire off a tweet telling the world even she couldn’t have predicted for whom her father would have cast his ballot and how it was completely wrong for anyone else to make such a claim) and essentially taking care to ascertain good intentions on the part of anyone venturing to cash in, if you will, on the Cash name.

‘Rabbit Hole,’ written by Rosanne Cash, from She Remembers Everything

Rosanne observes Rosanne in ‘Everyone But Me,’ from She Remembers Everything

On 2018’s She Remembers Everything—a telling title if ever there was one—Rosanne is about Rosanne, in the rawest form since 1990, when she released the brilliant, seething Interiors. But the latter was an album born of betrayal and deceit and a young, now-single mother coping, not always gracefully, with her new life; much water has gone under the bridge since then, as mentioned above, and so She Remembers Everything comes to us sounding like a mature woman taking a breath, taking stock, assessing herself in blunt terms and assessing the world around her, much changed since 1990, in direct, sometimes harrowing terms—“8 Gods of Harlem,” a co-write with Elvis Costello and Kris Kristofferson dating from 2008 but heretofore never released by any of these artists, began when Rosanne penned a verse about a child victim of a shooting and imagined how one tragedy not merely rippled but rather tore through the lives of his loved ones. Its edgy, electric soundscape recalls the ferocity of her 1993 gem, The Wheel, the first of her albums produced by John Leventhal, who should, finally, be recognized as one of the great producers of our time. Topical matters aside, we find the artist here more vulnerable than she’s ever admitted on record, and the sonics supporting her are similarly eerie and unsettling. On “The Only Thing Worth Fighting For,” the languid album opener with its heavily echoed, surf-like guitar, the pain and disorientation flows unceasingly, the singer telling someone, maybe us, “what I said was never what I meant/now you see my world in flames/my shadow songs, my deep regret”; on “Rabbit Hole,” one of five songs produced by Tucker Martine, the noir-ish backdrop frames a heartfelt homage to someone the singer has come to depend on to pull her up from the depths of, perhaps, depression or extreme self-absorption, to wit: “I want to make you see that you, in your crumpled splendor/when you sing to the farthest rafter/with your big life full of love and laughter/can pull me up from the rabbit hole.” Then there is “Everyone But Me,” an austere ballad with Cash’s reverent vocal backed only by Leventhal’s funereal piano abetted by a light wash of violins and viola. Herein Cash comes to grips with the legacy left her by her parents, and for the first time we see our hunch seemingly confirmed, that she has indeed focused on familial stewardship over personal care: “I gave up my name for you/gave up my edge, it made me bleed/and I pleased everyone, I mean everyone but me.” She sings not in anger but rather in benign acceptance of the truth of the matter: it was the right thing to do, as she suggests in the ambivalent refrain, “Mother and Father, now that you’re gone/it’s not nearly long enough/still it seems too long/it just wasn’t long enough/still it seems too long.” Later, in “My Least Favorite Life,” singing serenely over a forlorn twanging guitar and sad, foreboding strings, she ventures into the darker, confessional reaches of Melody Gardot territory in slicing and dicing a significant other in verses such as “This is my least favorite life/the one where you fly, and I don’t/a kiss holds a million deceits/and a lifetime goes up in smoke.” That rabbit hole she referenced in the album’s third song? The self-laceration only grows more intense, the cuts deeper, in brooding musings such as “Nothing But the Truth” and “Every Day Feels Like a New Goodbye,” songs whose mere titles say it all.

‘…all the harm I’ve ever done/alas it was to none but me…,’ from ‘The Parting Glass,’ a bonus track from She Remembers Everything

As it turns out, however, Rosanne has indeed been listening to the sound of her own heart all these years, but only now choosing to reveal so much of its complexity in one fell swoop. “8 Gods of Harlem,” remember, was written in 2008; several of the other songs began life in years past. If She Remembers Everything is any kind of chronicle, it’s a deeply personal one of a woman’s journey and her way of seeing the world evolve—the physical one and the inner one–as other endeavors demanded her attention. At the end, in the quiet, near a cappella strains (only Leventhal on guitar, mandolin and harmonium) of the ancient Irish traditional song (dating to the late 1700s), “The Parting Glass,” Cash puts the amen to this confessional by placing the weight squarely on herself, singing, “Of all the money ere I had/I am spent it in good company/and all the harm I’ve ever done/alas, it was to none but me/and all I’ve done…” Verily, she remembers everything. Doubt her not. –David McGee

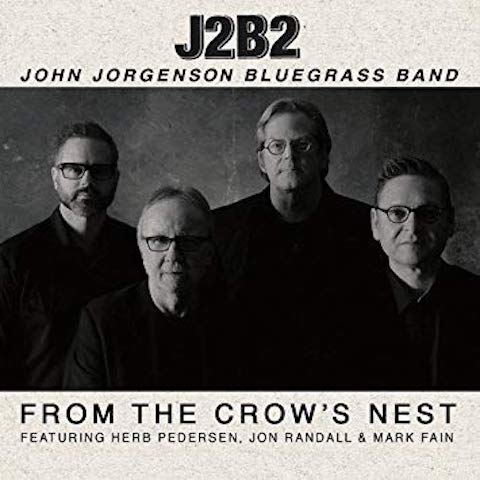

FROM THE CROW’S NEST, John Jorgenson Bluegrass Band (Purple Pyramid Music)– The bluegrass world has long spoken in hushed tones of the 15 tracks comprising one-third of John Jorgenson’s 2015 three-CD magnum opus, Divertuoso, an impeccably recorded trifecta of gypsy jazz, bluegrass and electric guitar-centered works. Finally, the ace guitarist-mandolinist has issued the bluegrass tracks as From the Crow’s Nest under the rubric of the John Jorgenson Bluegrass Band (or J2B2). With Jorgenson re-teamed with his Desert Rose Band compadre Herb Pederson (banjo), harmonies don’t come any sweeter (surviving the heartache they lay on you in “Wait a Minute” and absorbing the depth of expressed devotion in “If You Could See” are formidable tasks). With this dynamic duo supported by Jon Randall (guitar) and Mark Fain (bass) the musicianship is at the highest level—witness the collective fleet-fingered, high-wire mastery in the rousing instrumental “Gina” and the affecting lyricism in the banjo-guitar discourses fueling “Lady’s Bluff.” To put a fine point on the proceedings, the band closes with a potent, emotional reading of “Whiskey Lullabye,” the Jon Randall-Bill Anderson co-write taken to award winning heights by Brad Paisley and Allison Krauss in 2005. Here, then, is a real deal, true bluegrass landmark. –-David McGee

‘Wait a Minute,’ John Jorgenson Bluegrass Band, from From the Crow’s Nest

GHOST LIGHT, John McCutcheon (Appalsongs)–Thirty-nine albums. Think about that. In a recording career dating back to 1975, John McCutcheon still hasn’t sung it all. In 2018’s Ghost Light, he’s rarely been better. Well, storytellers don’t run out of stories to tell, but maybe the important point about McCutcheon’s art is how hope endures after all these years. There are generational shifts noted in Ghost Light, an acceptance of time moving on and things changing, not always for the better, but also of lives still playing out day to day, of the same tensions animating these days as they did his younger years, and how that ol’ wheel keeps on rolling. He says as much in the sprightly rhythms of the album opener, “Perfect Day,” spiced as it is with Stuart Duncan’s cheery, back-country fiddling and McCutcheon’s warm, bouncy vocal declaring, “It is a perfect night, it was a perfect day/I got to work, I got to write, I got to play/and I got to sweat and I really got to say/be hard to beat but I’d like to repeat this perfect day.” Let’s think about living, in other words. Follow this link to the complete review…

Storytellers don’t run out of stories to tell: ‘This Road,’ John McCutcheon, from Ghost Light

WHEN I RISE, Cary Morin (Maple Street Music)—Following the triumph of a solo acoustic album trilogy culminating in last year’s acclaimed Cradle to the Grave (a Deep Roots Album of the Year honoree, placing Morin in an elite group of multiple Album of the Year winners, along with Melody Gardot, Michael Martin Murphey, Rosanne Cash and Eric Bibb), Native American (from the Crow tribe) Cary Morin gets back to where he once belonged, with a stirring band album featuring enough of his virtuoso fingerpicking to satisfy those who came on board more recently complementing a clear leap forward in songwriting of a personal nature revelatory of an artist in his prime and, indeed, really feeling his oats. Recording at multiple studios with a rich, live sound, Morin’s stark, fingerpicked acoustic conjures the Delta while Lionel Young’s howling, desolate violin evokes the Great Plains in the album opening title track, which sets the agenda by being both a love song and a self-affirming statement of purpose. The easygoing “Let Me Hear the Music” adds a Dixieland element in Dexter Payne’s languorous clarinet as Morin lays down a sultry, Gregg Allman-ish vocal come-on over his rich guitar soloing. The full-on band assault of “Carmela Marie” reminds us Morin is a natural rock ‘n’ roller whereas the tender, fingerpicked “Devoted One” underscores the romantic in his sensibility. Beautiful work all around. —David McGee

‘When I Rise,’ Cary Morin, the title track from his Deep Roots Album of the Year

AUSTINOLOGY: ALLEYS OF AUSTIN, Michael Martin Murphey (Wildfire Productions)— Apart from enjoying the justified rave reviews for Michael Martin Murphey’s Austinology: Alleys of Austin triumph, your faithful friend and narrator has most appreciated the number of critics in and out of Austin properly recognizing Murph’s pivotal role in bringing national attention to the city’s vibrant music scene. Murph’s Austin years encompassed 1968 to 1972, the same years I was attending the University of Oklahoma. In 1968 we were introduced to Jerry Jeff Walker by way of his instant classic, “Mr. Bojangles,” but that minor hit single did a lot more for Walker than it did for the Austin scene. When Murph released his own instant classic in the form of 1972’s Geronimo’s Cadillac album (produced by Bob Johnston, released on A&M, a major label), I and everyone I knew in our local music community well north of Austin realized something serious was going on down there and started paying attention to, even seeking out, Austin artists. Soon enough we discovered the retooled Willie and Waylon, Townes Van Zandt, Gary P. Nunn, et al., and looked to Austin for something real we weren’t getting from mainstream country music. We weren’t alone: a Rolling Stone review of Geronimo’s Cadillac effusively praised the album and hailed Murph as “the best new songwriter in the country.”

‘Geronimo’s Cadillac,’ a defining Michael Martin Murphey hit reimagined for Austinology: Alleys of Austin, with an assist from Steve Earle

‘LA Freeway,’ a Guy Clark song from Michael Martin Murphey’s Austinology: Alleys of Austin, with accompaniment by The Last Bandoleros

But although Murph neither forgot nor downplayed his Austin roots, the general public came to know him as a major mainstream hitmaker when, in 1975, he hit the jackpot with the million selling single, “Wildfire,” and those Austin roots became less distinguishable as he transformed into a premier country balladeer in the ’80s. Then in 1990 he released Cowboy Songs and became, and remains, the foremost practitioner of western songs and high-profile champion of western culture. Come 2018 Murph reclaimed his pioneering mantle in Austinology: Alleys of Austin, a collection of mostly Murph originals with some choice covers—such as Guy Clark’s “LA Freeway” (Jerry Jeff’s second hit single, in 1973) and Townes Van Zandt’s beautiful, bittersweet “Quicksilver Daydreams of Maria,” sparsely produced and featuring one of Murph’s most affecting recorded vocals—all produced in spare settings, with acoustic guitars and pianos dominating the soundscapes and a backing band of strictly ace players on the order of Rob Ickes (dobro), Tim Akers (keyboards) and Kenny Greenberg (guitar). Murph and Steve Earle team up for an intense reading of “Geronimo’s Cadillac,” whereas Amy Grant joins in for a lovely take of “Wildfire.” In the case of Murph’s songs, the arrangements, though stripped down, evoke those of the original recordings, so the spirit abides. The Last Bandoleros join Murph for a furious attack on “LA Freeway,” the moment when the album rocks gloriously and majestically, and Murph’s intensity becomes most palpable. There’s no reason to believe the artist is now going to abandon the western songs he’s made his own for nigh on to three decades, but this project needed to see the light of day, and you can bet Murph knew he had, well, not scores to settle but history to correct. And so he does, with the grace, commitment and honesty he’s demonstrated on record from day one.

As a special bonus for Deep Roots readers, below is an excerpt from my 2005 biography of Steve Earle, Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet, in which is detailed the road Murph took to land in Austin when he did, and how the scene evolved during those critical years in its history. –David McGee

Lone Star State of Mind, 1970-1976

(Excerpt from Steve Earle: Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet by David McGee, Backbeat Books, 2005)

In Texas in 1970 a solid class of new artists emerged who were rejecting, in large part, what the country mainstream was offering. One of those setting the pace in Austin was Dallas-born Michael Murphey (who later used his full name, Michael Martin Murphey, to distinguish him from the actor Michael Murphey). Less an outsider than an insider with a saboteur’s instincts, Murphey didn’t reject the establishment so much as figure out a way to maneuver within its framework while playing by rules partly of his own making. He wasn’t merely testing the waters; he knew the waters well, having learned the nature of their ebb and flow at an early age. He was on the coffeehouse circuit, playing original material, by the time he was in high school and before going solo in his senior year performed with his friends Owen “Boomer” Castleman and Bob Jacobs in The Lost River Trio. By the time he was 18 he had his own TV show in Dallas.

Matriculating first to North Texas State College and then to UCLA in Westwood, California, Murphey continued writing and performing while studying classical literature, medieval and Renaissance history and literature, poetry, and creative writing. He started making a name for himself in the folk clubs, and in 1964 signed a songwriting contract with the publishing concern Sparrow Music. Another venture with Castleman ensued, this a band called New Survivors, whose other members were bass player John London, who had played on James Taylor’s debut album, and another aspiring singer-songwriter in Michael Nesmith, who would find success not as a New Survivor but as a member of The Monkees (who recorded a catchy version of the Murphey-Castleman-penned “What Am I Doing Hangin’ ‘’Round?”). After recording one unreleased album, the New Survivors disbanded. Murphey and Castleman carried on as a duo, Travis and Boomer, later re-branded, if you will, as the Texas Twosome, only to become a threesome when joined, on banjo, by formidable instrumentalist John McEuen, who later became a founding member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and remains one of acoustic roots music’s tireless champions.

‘Wildfire,’ a Michael Martin Murphey classic revisited, featuring Amy Grant, from Austinology: Alleys of Austin

When the Texas Twosome evolved into the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Murphey began to find not only a distinctive voice as a songwriter, but a mission as well: to fuse country, folk, and pop into a blend incorporating the lore and poetry of the Old West, whose history had been one of his life’s passions. Murphey spent his childhood years riding horses on his grandfather’s and uncle’s ranches. As a youth he had absorbed his family’s tall tales about the cowboys, Native Americans, notorious characters and great deeds done during the country’s push westward. Not least of all, he was enchanted by the cowboy songs he heard his relatives singing. Out of this the artist in Murphey emerged, his original works revealing a strong social conscience and a deep, abiding love of the land and nature. Unlike the New Survivors, the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s lone album did make it into the marketplace, but tanked despite some positive reviews. Thereafter, Castleman went his way as Murphey retreated with his new bride to a bungalow in the picturesque mountains above the Mojave Desert.

‘Quicksilver Dreams of Maria,’ by Townes Van Zandt, from Michael Martin Murphey’s Austinology: Alleys of Austin

The young man came down from the mountain in 1970 and moved to Austin, where he became one of the most popular artists in a burgeoning, and fertile music scene attracting a raft of gifted singer-songwriter types to the Austin-San Antonio-Houston club circuit. Notable among the venues of choice were Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters, the Id and the 11th Door; Houston’s the Old Quarter, Sand Mountain and the Jester. Murphey’s contemporaries included Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker, Guy Clark, the mercurial Townes Van Zandt, and bringing up the rear, a younger guard that included Houston-born Rodney Crowell and another native Texan, Steve Earle. Murphey was referred to by the locals as the “Cosmic Cowboy,” and legend has it that a then-strait-laced Willie Nelson caught one of Murphy’s shows at the Armadillo and was inspired to toss out his conservative suits and let his hair and his beard grow. Nelson would soon become an opening act for Murphey and the rest is history.

But Murphey and the others weren’t about just looking the part of outsiders. They were about asserting a fresh view of country music. “When I went back to Texas and Austin in the ’70s, everyone was pretty much listening to rock ’ n’ roll; but my idea, along with Willie, Waylon, and others, was to revive the songwriting ballad tradition of Texas and reconnect it to cowboy music,” Murphey recalled in an interview with The Performing Songwriter magazine. “My music had been influenced by rock ’ n’ roll and pop music, too, as well as the modern country music of the day, but I couldn’t get around the Western theme–it was all about loving the culture of my Texas roots. We were the hip, turned-on people of the time, but trying to salute tradition. This is what made Texas music different than anything else that was going on, because nothing else saluted tradition. Everybody else was trying to do something far out, and Texans were trying to reconnect with their roots in a turned-on way.”

WE RISE UP, Raven and Red (Line Crossing Records)– Hailing from Georgia and Pennsylvania, now Nashville-based, the Raven and Red trio (supplemented here by Paul Leech on electric and upright bass, cello and Justin Collins on drums and percussion) makes a great leap forward on its first full album following a 2014 EP and an impressive 2015 collection of Celtic music titled, simply, Celtic Collection. All but two of the dozen tunes are penned by band members Brittany Lynn Jones (a multi-instrumentalist featured on five-string violin, tenor guitar, mandolin, banjolin in addition to contributing affecting harmony and lead vocals) and guitarist Mitchell Lane, and let’s say they have it going on. These young adults either have lived with ferocity in matters of the heart and learned hard lessons or gleaned much from the experiences of those older and more seasoned in such matters. The remarkable aspect of their point of view, though, is the belief they advance of being undaunted in the face of romantic debacles. When Mitchell sings plaintively in “It Could Have Been You,” How can I trust that you love me now/when you didn’t love me then—sentiments he is addressing to an old flame suddenly popping up when he’s deeply committed to another—there’s no spite, no bitterness, really even no sadness—just a searing existential query hanging in the air. If anything, Raven and Red’s animating impulse is announced in the title track, which happens to close the album but which has been illustrated in many of the ten songs preceding it (the penultimate track is an impressive, near-seven-minute instrumental medley comprised of a reprise of an earlier song, “Wild Roses,” coupled to “Winter Raven” and “World Traveler”). To wit: We all wander together even when we walk alone/We rise up, we fall down, we get lost, and we get found/we hit dead ends and we turn around/keep pushing through to higher ground.

From Raven and Red’s We Rise Up, ‘Moonshine and Makeup’

So “pushing through to higher ground,” takes Raven and Red through much heartbreak and heartache along the way but somehow the journey is absent the numbing despair you might expect from romantic misfortune piled on romantic misfortune. Credit this abiding sense of hope not only to the writing but to the clear, ringing, expressive tenor voice of Mitchell Lane, a classically trained singer who delivers subtlety, nuance and expressiveness more common to much older souls with far more experience in life its ownself. Finding yourself slack-jawed at some of his performances would not be unusual. Follow this link to the complete review by David McGee…

THERE’S A PLACE FOR US, Nadine Sierra (Deutsche Grammophon/Decca Gold)– America’s founding colonists were sustained by the belief that they were building “a city on the hill”, a place that would serve as a model to all mankind. Countless migrants have journeyed there since to share the American dream. Simply put, Nadine Sierra’s story stands for the stories of millions whose families have made a fresh start in the United States. The critically acclaimed lyric soprano and Fort Lauderdale native, who celebrated her 30th birthday this past May, understands the essential contribution made by migrants to the nation’s growth. Her mother is Portuguese, whereas her father’s family hails from Puerto Rico and Italy. There’s a Place for Us, Sierra’s Deutsche Grammophon and Decca Gold debut album, pays tribute to the diverse backgrounds and creative energy of America’s classical composers. It also presents a timely reminder of unity and equality, of integration and optimism, at a time when anti-immigrant rhetoric is increasing, and fault-lines are widening between divided communities in the U.S. and beyond.

Recently named as winner of the Metropolitan Opera’s thirteenth annual Beverly Sills Award, Ms. Sierra believes opera and classical music hold the power to draw people together and promote universal values. The point is underlined by this new recording, which mines rich seams of American opera, song and musical theatre. The album’s program cultivates a sense that there’s a place for all, not in some future Utopia but right here, right now. Her choice of Bernstein’s “Somewhere” from West Side Story speaks directly to the immigrant experience while reinforcing hopes that peace will prevail over conflict. Sierra wants the message to be heard by those who fuel fear and stoke hatred of the other. The populist narrative of them-and-us, she notes, must be challenged: “I feel like this really needs to change, and I don’t think I’m the only one.”

With its eclectic choice of arias and songs, There’s a Place for Us embraces America’s multicultural, multi-ethnic mix. “I wanted to send an alternative message of positivity, unification, acceptance of all people no matter what race, no matter what sexuality, no matter what religion, no matter what anything,” comments Sierra. “I feel deep down that we can make a change in the right direction and that the right direction is about uniting people.”

‘There’s a Place for Us,’ Nadine Sierra, the title track from her Deep Roots Album of the Year

Stephen Foster’s Jeannie With the Light Brown Hair,’ Nadine Sierra, featured on There’s a Place for Us

There’s room in Sierra’s musical melting-pot for works by Leonard Bernstein, the son of Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants, and Stephen Foster, whose openhearted songs drew from his Scots-Irish heritage. The tracklist also includes compositions by Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov, Loyola Professor of Music at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Christopher Theofanidis, American-born son of a Greek pianist and composer who travelled to New York on a Fulbright Scholarship in the early 1950s. Igor Stravinsky, who lived in Los Angeles for almost three decades, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a frequent visitor to the United States, are part of the scintillating mix too. Sierra embraces the virtuosic demands of Anne Trulove’s aria from Stravinsky’s opera The Rake’s Progress, together with the lyrical flow of Villa-Lobos’s fifth Bachianas Brasileiras, a distinctly Brazilian take on the musical language of Johann Sebastian Bach, and the sensuality of Canção do Amor, which began life as music for the 1959 Hollywood film Green Mansions. Homegrown works by Douglas Moore and Ricky Ian Gordon complete the soprano’s survey of American music and are vital components of an album destined to stand the test of time.

BOOK OF J, Jewlia Eisenberg and Jeremiah Lockwood (3rd Generation Recording)– Jeremiah Lockwood is fast becoming a regular presence on the Deep Roots year-end best-of lists, most recently as 2016, when his Kol Nidre solo effort (a meditation on Yom Kippur’s traditional liturgy) earned Album of the Year honors, which followed by a year another Album of the Year award for his powerhouse solo blues outing, simply titled Lockwood. Well, Jeremiah is back, collaborating with the formidable Bay Area blues vocalist Jewlia Eisenberg on a truly mesmerizing project titled Book of J, so named after the texts comprising the origin of the Hebrew Bible (written, many scholars agree, by an unknown female author designated as J). Typical of Lockwood’s work, on his own and with his band Sway Machinery, the music reflects the gifted artist’s immersion in not only the Jewish liturgical music that is so much a part of his very being (he’s the grandson of one of the most revered American Cantors) but also blues (he was a long-time protege of the Piedmont blues man Carolina Slim), early rock ‘n’ roll, classical music, pop and world music in general. Working with Ms. Eisenberg has taken him even deeper into his roots, and if this recording reveals anything, it’s that Ms. Eisenberg both inspired and challenged Lockwood in the studio, resulting in a musical and spiritual dialogue for the ages. Writing in the Jewish News of Northern California, in a piece posted on September 21, 2018 and tellingly headlined “Where Delta Blues, Queer Liturgy and Yiddish Protest Songs Meet,” David A.M. Wilensky observes:

If there’s such a thing as the alt Jewish liturgical music scene, Book of J is part of it. The Bay Area duo’s self-titled debut album, released in July, somehow ropes together Delta blues, Yiddish protest songs, queer politics, black gospel and traditional Ashkenazi and Sephardic liturgical music into 12 coherent tracks.

The two singular musicians behind Book of J are Jeremiah Lockwood and Jewlia Eisenberg. Lockwood is the grandson of renowned classical cantor Jacob Konigsberg and is best known for his punk cantorial Sway Machinery albums. Eisenberg is the vocalist for the impossible-to-describe-in-one-sentence Oakland band Charming Hostess; ccording to a florid press release, she was “raised by a pack of feral Marxists” amid the music of social justice movements.

In a fascinating interview, Wilensky drew the artists out on the origins of and issues raised by the music on Book of J along with other topics. Some of the more revealing exchanges follow.

‘Tell Gd,’ fromBook of J, Jewlia Eisenberg and Jeremiah Lockwood

Among young Jewish activists on the left, there’s a rising consciousness around Yiddish music, Yiddish culture and the legacy of Yiddish political activism. You both grew up with that culture. Are you surprised it’s becoming trendy on the Jewish left?

Lockwood: I like it. I want there to be more of it. I’ve always been interested in Yiddish language and Yiddish modernist poetry. In the last few years, I’ve hunkered down with it more heavily, in response to the political situation. We’re in an age of radicalism. The resources of language and culture are really important in resistance. To the people I grew up with who spoke Yiddish, it wasn’t a political statement, it was just their identity. That kind of organic Jewish identity where language is integrated with daily life, is not so much a part of Jewish life in America now. I value it very highly. My doctoral thesis, which I’m working on now at Stanford, is about contemporary cantors in Hasidic communities in New York; those guys are all bilingual.

Eisenberg: I’ll pose a different question: Is diaspora consciousness rising among people who experience diaspora? Is it rising among different diasporas–Jews, African Americans, etc.? For me, that’s very powerful. I’m interested in giving voice to the intersection of text and diaspora consciousness. Diaspora consciousness is the most important frame of thinking in my life.

The Book of J contains political and protest songs from more than one language. Are they all traditional songs, or are some original?

Eisenberg: All traditional, every single thing. Leonard Cohen famously covered “The Partisan,” a song about the French Resistance in World War II, written by Anna Marly. People know this English version from Leonard Cohen, this is his arrangement. We want to have a deep engagement with different vernaculars. Is it political or is it folk? That song was a folk song, but it became a protest anthem. A lot of these songs were written by someone at some point, but they become vernacular, traditional. When it becomes sung by enough people, it becomes folk. Why do we want to sing it? Because we’re becoming anti-fascist partisans now! That’s who we are.

‘Do Lord,’ in rehearsal, from Book of J, Jewlia Eisenberg and Jeremiah Lockwood

Jeremiah, you studied when you were younger with the legendary African American blues guitarist Carolina Slim, but you also come from the world of traditional Ashkenazi cantorial music. Both of those are present on The Book of J. How do they relate to each other?

Lockwood: We’re in a way getting back to the Weavers, these folk records of the late ‘40s and the ‘50s, initial interactions–often Jewish–with American folk music, much of it African American. It’s maybe due to my own autobiographical story. Black music is a part of what I know and feel comfortable with. Cantorial music is yearning and aspirational, as a lot of black music is. I spent my late childhood and early teen years immersed in it. Maybe it’s ironic, but that’s a native tongue for me, almost more than hazanus [cantorial music]. That mix is part of being an American.

The Book of J is music with a message. What do you hope people will take away from the album?

Lockwood: That mourning, loss and feelings of longing are not pointless, that those feelings can be harnessed toward imagining and creating different stories, different ways of living that are better, less hurtful, that are reparative.

Eisenberg: I hope people feel interested in diaspora consciousness and direct anti-fascist action–and identifying that with their faith work, whatever the work is that they’re doing on their own faith.

Follow this link to the Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred of 2018, Pt. 1

Follow this link to the Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred of 2018, Pt. 2