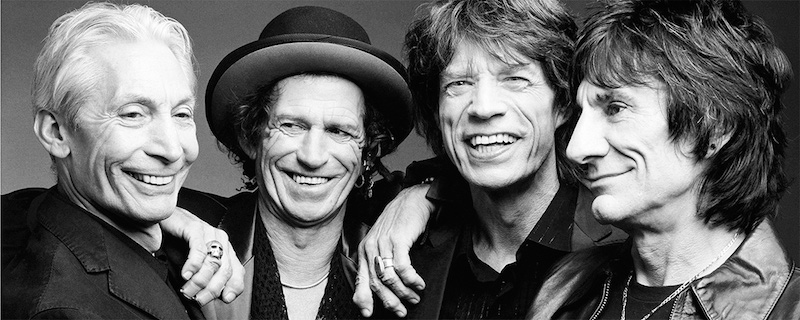

Deep Roots varies the number of albums it selects for Album(s) of the Year honors, the better to acknowledge the different genres we cover, the better to acknowledge recordings setting a new standard for the artists in question, or showing growth above and beyond the usual, or, in the case of The Rolling Stones last year, reminding us that they were not once great but remain great, if not consistently on record, at least on any given day. Their history cannot be denied and must be respected, but their present can produce amazing results too. This would certainly be true of two artists honored in a new category here, Retrospectives of the Year, wherein Paul McCartney’s self-curated 67-song solo career overview, Pure McCartney, and Rhonda Vincent’s All the Rage, the first of two planned live volumes documenting the powerful live show presented by Queen of Bluegrass and her long standing band The Rage–a first-ever documentation of one of bluegrass’s most important artists and bands. The eight honorees comprising Albums of the Year are presented in alphabetical order below, save for contributing editor Billy Altman’s appraisal of the Stones’s Blue & Lonesome, which simply demands–both for the insights Altman provides and for the very existence of the album itself–it be placed at the top. Without further ado…. –David McGee

***

Back to Basics

By Billy Altman

Blue & Lonesome

The Rolling Stones

Interscope

History notes that it was precisely twenty years to the day after the World War II Invasion of Normandy when, on June 6, 1964, the Rolling Stones made their American television debut on ABC’s Hollywood Palace–the Saturday night prime time variety show hosted each week by a different showbiz celebrity. As it happened, Dean Martin was emceeing the program, and what ensued spoke volumes about the seismic musical, and cultural, shift that would soon be known as the British Invasion. Though the Stones played several songs at the taping a few days before, when the finished show aired, the band was onscreen for a grand total of less than 80 seconds – a performance of “I Just Want to Make Love to You” that was both preceded and followed by a series of condescending remarks and askance glances by Martin in all his ring-a-ding-ding Rat Pack “hipness.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJFjL8Rp-9A

The Rolling Stones on Hollywood Palace, June 1946, performing Buddy Holly’s ‘Not Fade Away’ and the Willie Dixon-penned, Muddy Waters-recorded ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You.’ Posted at YouTube by marslife01, who further notes, ‘Dean Martin makes a fool of himself.’

Of course, one of the things that’s most striking about this little slice of Generation Gap surrealness is the fact that the song the Stones were playing was written by Willie Dixon, and originally recorded by Muddy Waters–names that at the time meant little or nothing not just to Dean Martin, but virtually all of mainstream America, but already meant an enormous amount to not just the Rolling Stones, but virtually all the young British musicians who were starting to make their presence felt on the American side of the Atlantic. And while neither Dixon nor Waters would have been able to come within a mile of the Hollywood Palace in 1964, the Stones, on their maiden tour of the US, made it a point to visit, and record, at the vaunted Chess studios in Chicago. Within a year, the Stones would have enough commercial clout to force Jack Good, producer of another ABC prime time program, the teen music show Shindig, to air a live performance by another blues Chess master, Howlin’ Wolf, whose Dixon-penned “Little Red Rooster” the Stones had also recorded and turned into a British chart-topper. (And please note, at the start of the clip, seated at the piano on the bottom left of the screen, none other than then Shindogs houseband member Billy Preston):

The Rolling Stones on Shindig, 1965. The band’s begins with ‘Down the Road Apiece,’ a 1940 tune written by Don Raye and recorded in a Top 10 hit version that year by the Will Bradley Trio. Often covered, it was rewritten and recorded by Chuck Berry in 1960. A year later Henry Mancini was hired to write the score for the film Hatari, starring John Wayne and directed by Howard Hawks. While screening Hawks’s footage of elephants walking to a watering hole, Mancini realized their pace was ‘eight to the bar,’ as he recalled in his autobiography, which in turn reminded him of the original boogie-woogie version of ‘Down the Road Apiece,’ which in turn begat ‘Baby Elephant Walk,’ which in turn won a 1962 Grammy for Best Instrumental Arrangement. A vocal version with lyrics by Hal David was recorded by Pat Boone in 1965. The Stones’s Shindig set continues with an amused Mick performing ‘Little Red Rooster,’ written by Willie Dixon and originally recorded by Howlin’ Wolf, in a graveyard setting before he moves up to join the band. From there the band kicks into ‘The Last Time,’ the first single written by Jagger-Richards (adapted from a traditional gospel song, ‘This May Be The Last Time,’ recorded in 1958 by the Staple Singers), followed by its B side, ‘Play With Fire,’ the recorded version of which features only Mick (on vocals and tambourine) and Keith (acoustic guitar) with producer Phil Spector on bass (a tuned-down electric guitar) and arranger Jack Nitzsche on harpsichord. The Stones wind up their extended appearance with a version of the band’s new single, a ditty called ‘I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.’

Fifty-plus years later, who knows how much any of this might have been in the consciousness of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards or Charlie Watts last December, when they gathered, along with “newer” Stones members Ron Wood, Darryl Jones, Chuck Leavell and Matt Clifford for rehearsal sessions for what was ostensibly going to be an album of new originals–sessions that evolved (or devolved) into a three day wing-it spree of blues covers that resulted in Blue & Lonesome. But judging from the spirit, if not necessarily the letter, of this album, it is a significant achievement–a reminder that beneath everything that went into giving the Rolling Stones their title of “World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band” (back when that title actually meant something) there has been, and remains, a foundation built on a reverence and respect for the blues. And the fact that this first new studio album by the Stones in over a decade has already resonated with listeners far more deeply than anything they’ve recorded since, realistically, 1989’s Steel Wheels (and we’re being generous) speaks to the durability of that foundation.

Little Walter’s ‘Hate to See You Go,’ The Rolling Stones, from Blue & Lonesome

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XPvTdlOjRSw

Mick Jagger interviewed on BBC Breakfast, December 2, 2016, on the making of Blue & Lonesome

From CBS Sunday Morning, Mick and Keith talk about discovering the blues and what the music meant to them, with correspondent Anthony Mason.

It does not seem like mere coincidence that of Blue and Lonesome’s eleven songs, four come from the gem-filled catalogue of Little Walter Jacobs, the harmonica giant who graced so many Muddy Waters classics in the 1950s while also recording many of his own before his untimely death from a street fight at age thirty seven in 1968. Walter’s solo recordings balanced his own nimble singing and playing with interlocking twin guitar parts (usually from brothers David and Louis Myers, and later from Robert Jr. Lockwood and Luther Tucker), and here, on “Just Your Fool,” “I Gotta Go,” “Hate to See You Go” and title track, Richards and Wood admirably channel those guitar teams, bobbing and weaving around each other with the kind of instincts that can only come with the forty years experience they’ve had playing together.

Kristen Stewart (from The Panic Room, the Twilight series, et al.) stars in the video for the Stones’ version of Eddie Taylor’s ‘Ride ‘em On Down,’ from Blue & Lonesome

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PacX2YgdLOo

‘Just Your Fool,’ The Rolling Stones, from Blue & Lonesome. Originally written and recorded by Buddy Johnson, with his orchestra, in 1953, it was adapted and covered by Little Walter in 1960. In 2010, a Cyndi Lauper cover version, with Charlie Musselwhite on harmonica, was featured on her Memphis Blues album and performed live, with Musselwhite, on Celebrity Apprentice.

Meanwhile, Jagger’s singing, on these tunes and on the album as a whole, recall his early days as a vocal shape shifter capable of sounding alternately playful (“Fool”), pernicious (Howlin’ Wolf’s “Commit a Crime”), or just plain peeved (Little Johnny Taylor’s soul blues evergreen “Everybody Knows About My Good Thing”). And if there’s one real revelation on this album, it’s Jagger’s impressive harmonica work, which is front and center on nearly every track, and shows a casual command that, again, really only comes with a lifetime of playing.

‘Everybody Knows About My Baby,’ The Rolling Stones, from Blue & Lonesome, originally recorded by Little Johnny Taylor

While it’d be a stretch to say that any of performances on Blue and Lonesome really equal, let alone surpass, any of the source originals, it is, as stated before, the spirit of this album that makes it genuinely special; there’s an intimacy, and an honesty, that permeates every track. More than anything else, Blue and Lonesome finds the Stones sounding as if they’re simply playing for themselves, for the sheer enjoyment of the shared experience, and with a humility that befits their unique relationship to the magic and mystery of that deceptively simple yet profound style of music called the blues. It’s what inspired and propelled them in the first place, and as evidenced here, it’s what’s still inspiring and sustaining them. Somewhere, Ian Stewart, and maybe even Brian Jones, are smiling.

***

LONE STAR: SONGS AND STORIES STRAIGHT FROM THE HEART OF TEXAS, Glenna Bell (Glenna Bell)

We’ve waited six years for a new Glenna Bell album to follow up her widely acclaimed 2010 gem, Perfectly Legal: Songs of Sex, Love and Murder. With Lone Star: Songs and Stories Straight From the Heart of Texas, this most literate of songwriters adds an intriguing new chapter to her body of work. However frustrating the wait for this long player, its contents reward her fans’ patience.

‘Shiner Bock & Zz Top (Houston Avenue),’ Glenna Bell, from Lone Star: Songs and Stories Straight from the Heart of Texas

Once hand picked by Edward Albee for his playwriting class at the University of Houston, the Port Arthur, TX, native instead gravitated to songwriting. The theater’s loss became music’s gain, but the fact is Ms. Bell’s songwriting style is deeply rooted in her sense of theater. Her quavering voice, one of the most distinctive in roots music, enhances the intensity of and adds layers of complexity to narratives that rivet a listener by dint of Ms. Bell’s gift for dramatic structure and characterization, with the X factor being the curious power of her deliberate vocal delivery to get into your marrow. Glenna Bell songs are like no others. This is true whether the subjects be down-and-outers trying to find both love and inner peace (the atmospheric guitar-vocal ballad “Poor Girl [In Blue]”); or a fellow’s unfathomable attraction to the most unattractive of his distaff options (the jaunty “Pig in Lipstick Blues,” featuring Johnny Nicholas in two swaggering solos, one on guitar, the other on piano); or a tough-as-nails Houston gal from another time, another place in the old city (the tender, fingerpicked reminiscence “Shiner Bock & Zz Top [Houston Avenue]”). Add a couple of tasty covers to the mix (especially the band Keane’s “Everybody’s Changing,” here realized as a piano-based waltz evoking 19th Century parlor songs) and producer Kevin “Big Kev” Ploghoft’s typically rich sonics, and voila! An Americana classic. –David McGee

***

C&O CANAL, Eric Brace & Peter Cooper (Red Beet Records)

It seems entirely appropriate that the first sounds emanating from Eric Brace & Peter Cooper’s fourth duo record, C&O Canal, are the two of them harmonizing on the opening lyrics of the John Starling-penned title track, to wit: “Heeeyyy-heeyyy-heeyyy, lock ready…whoa, hey-hey lock…” It’s a reverent, poignant memory song about days and nights on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal that starts in Washington, D.C. and ends in Cumberland, MD, as recalled by an elderly gent reflecting on his long-ago youth as a canal worker. In setting the stage for the old-timer’s reflections on the world he used to know, the gospel flavor of Brace and Cooper’s opening harmony salvo tells us we are on holy ground here. The other nine songs on C&O Canal merely reinforce this notion.

The holy ground is both literal and figurative, the former being the songs themselves, the latter the natural world in which the songs are set and which has a direct impact on the characters’ lives, as well as those of the artists featured herein. This is not an album of Brace and Cooper originals, but rather their tribute to the formative years they spent honing their musicianship in the Washington, D.C. area, which once, thanks to groundbreaking bands such as the Seldom Scene, and legendary clubs such as the Birchmere, was hailed as the “Bluegrass Capital of the World.” The 10 songs are drawn from the catalogues of songwriters associated with the D.C.-area scene, including three tunes by the Seldom Scene’s great John Starling, and the incredible “John Wilkes Booth” by one of the scene’s noted mainstream artists, Mary Chapin Carpenter.

‘C&O Canal,’ written by John Starling, in a live version of the title track of the latest album by Eric Brace and Peter Cooper. With Andrea Zonn on violin. Performance from Music City Roots, February 17, 2016.

Brace and Cooper are an awe inspiring duo—they sing, write, play and produce with equal authority and hearts full of soul. In their voices here you hear the deep feeling they invest in each tune and you sense the intensity of their conviction in this effort. It’s impossible to pick out one moment as surpassing another; just when you think Cooper’s aching reading of the Emmylou Harris-Bill Danoff classic “Boulder to Birmingham” (with plaintive distaff harmony courtesy Andrea Zonn, who also adds heart tugging violin support to the track) is nothing less than transcendent, Brace has you playing and replaying the harrowing narrative of “John Wilkes Booth,” Ms. Carpenter’s artfully compressed take on the conspiracy to assassinate the President and events immediately preceding and following the principals’ fateful destiny, herein a story played out over an unassuming arrangement, featuring a loping rhythm, a soft shuffle on brush drums (by Lynn Williams), their partner Thomm Jutz’s timely acoustic guitar embellishments and Ms. Zonn’s atmospheric violin.

‘John Wilkes Booth,’ written by Mary Chapin Carpenter, as recorded by Eric Brace and Peter Cooper on C&O Canal

What’s not to like, or to marvel at? Brace and Cooper lay you low with their evocation of abject loneliness and heartache in Starling’s “He Rode All The Way to Texas,” a western-style ballad of a peripatetic wanderer whose sorrowful state is made doubly vivid by unfolding over a backdrop dominated by accordion (Jeff Taylor) and dobro (Justin Moses) that summons the sense of a man alone under the big sky and an endless horizon, a vista as devoid of hope as the protagonist is of companionship. A woman finally realizing the folly of a relationship with a selfish partner and thus preparing to set a symbolic table for one goes the storyline of Karl Straub’s “Rainy Night in Texas,” a matter-of-fact revelation set to a loping arrangement fueled by banjo and dobro over which Brace and Cooper execute a masterful duet in which the narrator’s voice is completely composed but also, in tense choruses, betraying her internalized fury. From Joe Triplett of the Rosslyn Mountain Boys, our heroes assay “Been Awhile,” complete with a rich, swirling soundscape again dominated by accordion and dobro as Brace gets a bit bluesy in relating the feelings of a man who may be on the precipice of misfortune but is also feeling himself renewed by the natural world in which he’s luxuriating at the moment.

‘Been Awhile,’ written by Joe Triplett, from Eric Brace and Peter Cooper’s C&O Canal

‘Boat’s Up the River,’ written by John Jackson, from Eric Brace and Peter Cooper’s C&O Canal

So it is that C&O Canal finds its characters inseparable from and often formed by the environment around them, as in the songs noted above and in others, such as Alice Gerrard’s ominous “Love Was the Price,” set in coal country despair; in the album closing “Boat’s Up the River,” a jaunty, old-timey musing about lost love from John Jackson; and in “Blue Ridge,” a close-harmonized love song to home co-written by the Allegheny Drifters’ Bob Artis, who is credited with having authored the first history of bluegrass music (Bluegrass, published in 1975). As solo artists and as a duo, Eric Brace and Peter Cooper get better each time out, but they have made the jump to light speed with this latest burst of brilliant music making. Cleary the Force is strong in them. –David McGee

***

ANIMAL INSTINCT, JJ & Co. (James Justin & Co.)

Perhaps the key to JJ & Co.’s 2016 album Social Animal is found on its second song, “Turn This Thing Around.” We’ve heard this tune before: James Justin Burke (the JJ of JJ & Co) featured it on his 2010 debut release, Southern Son, So Far (reviewed in the November 2010 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com, this publication’s original incarnation), in a slightly different, and more sever, version. As I described it in the original review: “…he feels free to admit to insecurities, even failings, yet resolves to work with his partner on restoring their unique harmonic convergence (“One by one, we’re gonna get up off the ground/two by two, we’re gonna make each other proud/three by three, we’re gonna try to turn this thing around”—“Turn This Thing Around,” which begins as an eerie, chilling dirge on the strength of Jesse Pritchard’s mournful violin, Bailey Horsley’s spare, lonely banjo and Dave Vaughan’s tear-stained mandolin lines, before breaking into a joyous, celebratory bluegrass lope as Burke anticipates the healing moment’s arrival)…” Six years later, something has changed. The dirge-like intro is gone, so is the mandolin, replaced by a more reflective mood crafted by a lone, tenderly picked acoustic guitar that soon breaks into a gentle lope as a piano eases in behind it, and then the fiddle enters with a keening cry with Horsley’s banjo adding a laconic vibe to the scene ahead of Burke’s vocal. The JJ of 2016 is changed from the James Justin Burke of 2010. The once-reedy voice that grabbed your attention by the force of its urgency is now warm, earthy, a voice of experience that knows the “one by one” chorus articulates a sure thing he’s going to make happen. When the music breaks into a jubilant banjo-fired bluegrass strut, his is the voice of triumph, knowing that he’s going to “turn this thing around.”

‘Shiver (Fin’s Song),’ JJ & Co., from Social Animal

One of his generation’s finest songwriters, Burke arrives with JJ & Co. at yet another place from where we’ve found him on his previous three albums, including 2011’s Dark Country (reviewed in the November 2011 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com) and Places, a 2014 Deep Roots Album of the Year selection. As he noted in an interview with www.follybeach.now.com, Southern Son, So Far was “about my wife and how she changed my life.” Dark Places continued to explore the complexities of relationships and the depth of love, but it also saw relationships as a metaphor for a nation’s ills, notably in the powerful title track, one of the most challenging songs in the Burke catalogue. Quoting now from my album review in reference to that song: The more Burke sings, the more cryptic the story becomes–it’s not about two people anymore. It’s about the malaise sweeping over an entire dark country, where lunatics are trying to turn back the clock on workers’ rights, womens’ rights, voting rights, are getting away with it, and we are all complicit in the ensuing horror–“no place to run and hide/X marks the spot where you’ll sign/no one gets out clean/it’s a cold and…dark…countreee…” Who knows if this is interpretation even comes close to Burke’s intentions in writing the song, but it makes sense given that in the “Dark Country” video he is seen in a closing shot running down a street holding aloft a flag of the original 13 colonies of the United States–a reminder, perhaps, of the principles on which the country was founded and which now seem under daily assault? Works for me.

‘Hold on Tight,’ JJ & Co., from Social Animal

Places, however, found Burke breaking free from the relationship themes, with the album title being most telling. Again, from the Deep Roots review: After two albums very much rooted in philosophical musings on the nuances of personal relationships, especially those of a romantic nature, Burke, accompanied by his trusted musical mates Bailey Horsley (banjo) and Tom Propst (bass), with whom he has long performed as James Justin & Co., plus a smidgen of supporting instrumentalists, seems to have shelved relationships as an animating impulse for his songs. Instead, his focus is on the land, almost exclusively on the land, as inspired by what appears to have been an epic cross-country journey.

But on reflection, Places seems less anomaly than logical progression, a more expansive discourse on his heart’s stirrings than was revealed in the interior dialogues of his debut, Southern Son, So Far (2010), and its unforgettable followup, Dark Country (2011). And though people do figure into some of these scenarios, Places is really about the effect the land, the natural world, had on him as he arrived at each new destination on his journey—that is to say, the land is as much a living, breathing character on this album as Burke himself.

On Social Animal (available as of this writing only at the JJ & Co website, as a download only) Burke is back home (a Virginia native, he lives in Folly Beach, SC), and he’s now a father—the sixth track, “Sleep Well,” begins with his wife asking their little boy a series of questions: “Can you say rock ‘n’ roll? Bailey? Can you say Tom? Can you say Daddy?” He gives all the right answers, but when she asks “Can you say JJ and Co.?” he shouts gleefully, “Daddeee!” At which point Daddy enters singing an upbeat, gospel-tinged lullaby. Later, on “Shiver (Fin’s Song),” in which an a cappella intro opens up into the quintessential JJ gallop, ebullient, backwoodsy and driving, rich in harp and acoustic guitar, in which Burke returns to a familiar sentiment, “I was lost but now I’m found/you helped me turn this thing around/it’s amazing…” The magnificent soundscape showcases a positively ecstatic mandolin solo before Burke reprises an earlier sentiment with spiritual overtones: “I’ll teach you about the river/never let you shiver…” Which tune leads us directly back to Southern Son, So Far, and a new version of that album’s shambling hoedown, “Come On Me.” Except instead of plunging into the maelstrom, as the band does on the first intense, frolicking version, the 2016 version, clocking in at 7:17, in contrast to the original’s fleet 2:38, offers what amounts to a banjo mini-suite, 3:40 of rapid rolls with softer, reflective passages interspersed, duration at the start, before Burke steps up with a warm, deliberate reading of lyrics he sang so emphatically on his first album but now, with time, offers with the conviction of renewed vows: “Count on me to be your best good friend/stay until the end/true love can you see/baby, I’ll be…count on me…always be”—at which point he lets out a shout like we’ve not heard from him on disc before— “Yeeaahhh!”/keep you in my heart, right there from the start/true love can you see…” It’s so subtle a performance you don’t really notice that the pace has picked up dramatically as the song unfolds.

‘Count on Me,’ the 2016 version, JJ & Co., from Social Animal

‘Turn This Thing Around,’ the 2016 version, JJ & Co., from Social Animal

Other songs always seem to circle back to his loved ones and the junction between his music, his family, and indeed, his interior life, whether it’s in the rousing “My Love” (in this instance, “luck” may be human or providential) or in the delightful shuffle of “Hold On Tight,” a tune both celebratory and revelatory in that amidst the spirited goings-on defined by bass, shaker, banjo and hand claps, Burke admits, “Looking back I don’t know what I see/someone who’s scared to face reality now/looking back I didn’t know what to say/dig it up, get it all out the way now/you gotta hoooold on tight/you gotta hoooold on tight/take it back, take it back all the way now…” and in doing so reflects on who James Justin Burke was when first we encountered him on Southern Son, So Far and how far he’s come since then.

‘The Break,’ JJ & Co., from Social Animal. Posted at YouTube by Richard ‘Dickey’ Brendel of IndigoCoast, who was inspired to shoot the music video after hearing the song. The surfer is Kate Barattini.

At the end, on “Outro (New Shirt),” guitarist Burke introduces a repeating, descending guitar figure, then comes on the track speaking to the listener and offering thanks for listening to the record, citing a Stephen King quote–“Some birds are not meant to be caged. Their feathers too bright, their songs too sweet and wild.—to which he adds the addendum, “I say there’s a bird in all of us, and we’ve gotta set him free.”

Clearly, Social Animal ‘s larger message is that, finally, over the course of four albums, James Justin Burke has set himself free. For considering the question of where American roots music goes from here, well, I know the answer: it follows JJ. –David McGee

***

DEATH’S DATELESS NIGHT, Paul Kelly & Charlie Owen (Cooking Vinyl America)

From casual musings concerning songs they had been requested to sing over the years at, of all things, funerals, veteran Australian roots artists Paul Kelly and Charlie Owen produced Death’s Dateless Night, a spare, thoughtful but life affirming collection radiating profound humility occasioned by the event for which these tunes were summoned. Sounding like a rustic Roger Miller, backed by his own guitars and Owen’s nuanced support on lap steel, dobro, synth and piano, vocalist Kelly conjures a mood both reverent and respectful, “a sigh that is wafted across the troubled wave,” a la the hymn-like piano-and-vocal reading of Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times.” Spirit is made human in the unvarnished personal testimony of Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire”; in the understated intensity for life lived vividly in a countrified ballad treatment of Townes Van Zandt’s “To Live is To Fly”; and, perhaps most surprisingly, in a sweet but assertive version of Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In,” wherein the singer’s affection for personal liberty and God’s green earth is underscored by Owen’s ringing lap steel and daughters Memphis and Maddy Kelly’s innocent, Patience & Prudence-like harmonies. To quote another song here, “there will be an answer/let it be.” –David McGee

‘Hard Times,’ Paul Kelly & Charlie Owen, from Death’s Dateless Night

***

KOL NIDRE, Jeremiah Lockwood (Because Jewish)

Jeremiah Lockwood, the bandleader of the Brooklyn-based cantorial-rock group, The Sway Machinery, has released a meditation on Yom Kippur’s traditional liturgy entitled Kol Nidre, a collaboration produced by Rabbi Dan Ain of Because Jewish. The album works as both a modern update and a sustaining force of the title track’s traditions. Where cantorial music has been relegated to few figures and even fewer ritual moments, Lockwood and The Sway Machinery offer a nuanced and relevant translation of an arcane musical tradition without displacing its complexity and force. As he’s done previously, he voices in this work the blues in cantorial melodies, the mythical reach of some of the most obscure liturgical texts, and the rhythms shared by both cantorial and other soul musical traditions. …

Lockwood, the grandson of renowned American Cantor Jacob Konigsburg and student of Piedmont blues legend Carolina Slim, is at ease fusing various soul traditions. Over the last seven years, he and his brass and rock band have innovated three previous albums, Hidden Melodies Revealed (2009), The House of Friendly Ghosts (2011), and Purity and Danger (2015), each of which explore a cantorial tradition mixed with the rhythms and tones of blues, folk rock, and Afropop.

Official music video for Jeremiah Lockwood’s ‘Raise the Dead,’ from Kol Nidre

Unlike the band’s previous albums, however, the songs on Kol Nidre highlight Lockwood’s vocal virtuosity in ways that foreground the cantorial over the instrumental. The effect is one that retains the liturgy’s traditions, perhaps honoring their worshipful origins and homes.

At once stylized and minimalist, this album’s songs foreground Lockwood’s iconoclastic cantorial blues while backed by Lockwood’s own plucked strings and slide guitar, Shoko Nagai’s organ, and John Bollinger’s percussion. The opening, middle, and final tracks of Kol Nidre are varied renditions of the album’s title—a nod to the melody’s repetition three times in the traditional liturgy. And these riffs on Kol Nidre punctuate an assortment of takes on traditional melodies, ranging from the folksy to what can only be described as cantorial-psychedelic. Follow this link to Hillel Broder’s complete review of Kol Nidre, “Jeremiah Lockwood’s New Cantorial Blues Album, Kol Nidre, Is a Yom Kippur Dream,” published at Lehrhaus.

***

IF THE STATIC CLEARS, Gabrielle Louise (Sandalwood Records)

Although she doesn’t come from a theatrical background a la Glenna Bell, Colorado-based Gabrielle Louise grew up with theater all around her. Her parents were traveling musicians (her father, Paul Sadler III, was Michael Martin Murphey’s lead guitarist for 20 years, and, billed as Los Dos and Mother Gabrielle, also one-half of a duo act with Gabrielle’s mother), and Gabrielle has said mom and dad hoped their daughter would be a performer and gave her a name suited for the stage. It turns out she’s suited for more than the stage. Influenced as much by poetry and prose as by music, hers is a literary voice—comparisons to Joni Mitchell are apt and rampant—more focused on the storyline and character development than on a smooth flow of rhyming verses. If her songs demand a bit more of a listener, then the payoff is worth the extra effort it requires in order to see everyday situations and feel commonplace emotions in a different way. Veteran bluegrass bassist/producer Gene Libbea, who produced Ms. Louise’s striking second album, Cigarettes for Sentiments, says, “She’s very descriptive. Her songs do tell a story. If a songwriter is able to tell a story, and if they’re able to put pictures in your mind, I think they’ve done their job. If you don’t get anything in your mind, but it sounds good, but you don’t know what they mean…I’ve run into that before.”

‘Breathe Easy,’ Gabrielle Louise, from If The Static Clears.

If The Static Clears represents the apex of Gabrielle Louise’s art. It’s been a steady progression, beginning with Cigarettes for Sentiments (which earned the artist a cover story in the February 2009 issue of this publication’s original incarnation as TheBluegrassSpecial.com) and leading to 2013’s masterful The Bird In My Chest (#9 on that year’s Deep Roots Elite Half Hundred). Note the conditional nature of her new album’s title: not when but if the static clears. So it is when you get to the last song, “Where Love Lives,” a spare beauty with folk and western song influences (acoustic guitar, a softly crying dobro) that seems to be about a loving couple that have everything it takes to build a life together, things are still a tad unsettled. In her clear, ringing, gentle vocal, Ms. Louise observes, “All you have to have in common is the will to give/and the heart to build a home—“—pause—“where love lives.” The ambiguous pause says it all, as if some key element is missing from an otherwise heartwarming scene. In the album’s tender opening song, “Breathe Easy,” love rules but one partner is clearly, well, ambiguous about commitment, a condition for which Ms. Louise’s character offers a stress-free solution: “I’m not asking to settle down/you can come and go as you please/inside your kiss I drown/I drown and I breathe/breathe and I drown, drown and I breathe/breathe and I drown, drown and I bre-e-e-a-a-a-the (pause) easy…” No album in recent memory has made better use of pauses to add crucial ambiguous subtext to seemingly unambiguous declarations. (Maybe we should make a pause ourselves here, to note that Leonard Bernstein, in one of his Harvard lectures released as The Unanswered Question, noted that the very definition of “ambiguous” is in fact ambiguous.) The conditional “If” is no better articulated than in arguably the album’s most moving song, “Someone Else’s Life,” inspired by summers spent in Buenos Aires. Ms. Louise’s conversational vocal and delicately fingerpicked guitar, a soft, soothing flute, a discreet upright bass low in the mix and a harmonizing velvety female voice comprise a spare soundscape redolent with echoes of early music, the better to lend a Pinter-esque sense of surface serenity to a narrator’s story of seemingly being at peace with her conventional life, until the choruses reveal her inner tumult. In the first we’re told “I want to wash up on the shore…and I’m waitin’ to be found…” followed by a keening, falsetto “ooohh, but the sea is still…ooohh” (pause) “…what do I feel?” She sees her life in “boxes on the floor” and laments how “it’s unfair to him to come around when I’m feeling torn/so for now my heart hides/inside of someone else’s life…” In the park parents lift happy children in their arms, dusk settles in, and a thought arises: “I want to wrap him up around me/wear him until he’s worn/for now my heart beats/inside of someone else’s dream/mine is waiting to be born.” A short guitar glissando and the story is over, with the narrator still adrift existentially.

‘Someone Else’s Life,’ Gabrielle Louise, from If The Static Clears

Apart from the issues she explores lyrically and the always captivating atmospheres enhancing her stories, Ms. Louise offers a bold mix of styles here. “Love On the Rocks” has a dark, noir-ish quality and a shambolic arrangement with Tom Waits overtones about it to accompany her dramatic, swaggering vocal; “Waiting to Give” is a flat-out country kissoff, all gentle shuffle, backwoods fiddle, weeping pedal steel and a vocal reading full of rural twang like we’ve never heard before from this artist; “Another Round on Me,” a slow bluesy number with feet in both country and jazzy saloon song styles, has a topical edge and finds Ms. Louise sometimes phrasing uncannily like Trisha Yearwood; otherworldly effects, shifting sonic textures and a cabaret-like vocal approach rife with foreboding darkness heighten the cinematic effect of “The Graveyard Ballet”; and speaking of cinematic, “No Moon at All (For Frida),” a 6:22 perspective on the tumultuous love affair/marriage (actually, they were twice married) of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera is essentially a mini-suite rooted in a Spanish-flavored but shifting sonic backdrop in which guitars fall in and out, sometimes leaving but a lone, haunting snare drum behind the vocal. Apropos of the ebb and flow of the subjects’ relationship, and of the complexities of relationships as Ms. Louise explores on If The Static Clears, this evocation of two gifted but fiery-tempered and sensually driven artists fades out in proper ambiguity: “After Frida no one ever loved Diego/Like a fire in a wheat field under a fountain of stars/when they first kissed the street lamps sparked”—pause—“and dimmed.” Then, silence. But the heart is moved, as art so deep and real as this is wont to do. –David McGee

***

HIGH STAKES: COWBOY SONGS VII, Michael Martin Murphey (Murphey Kinship Recordings)

On the seventh installment of his celebrated Cowboy Songs series, Michael Martin Murphey—long a for-real rancher in addition to being America’s foremost advocate for the cowboy, both in song and in his environmentally beneficial lifestyle—deploys his own tunes and complementary covers to construct a narrative of humans being formed, and transformed, by nature. Witness the latest of six generations of cattlemen bucking the odds of a dwindling market in the Irish-tinged “Three Sons”; the young man engulfed in “sinful living” who hears a divine voice calling him to the straight and narrow when the sky opened up while he was in the midst of rustling cattle, as recounted in a powerful reading of Marty Robbins’s classic Western melodrama-in-song, “Master’s Call”; the soul enriching virtues of living in the natural world chronicled in the thoughtful piano-and-fiddle-based ballad “Campfire On the Road,” in which Murph urges, “We must never let them take this life away.” Assaying another high-stakes issue, he addresses a relationship’s end in a tender, acoustic-based sayonara “The End of the Road.” Boasting sonics as clear and refreshing as the rivers running through some of these songs, High Stakes is a topical gamble offering an inspiring payoff. The listener holds the winning hand. –David McGee

‘Honor Bound,’ Michael Martin Murphey, from High Stakes: Cowboy Songs VII

***

Follow this link to the Retrospectives of the Year 2016

Follow this link to the Elite Half Hundred of 2016, Part 1

Follow this link to the Elite Half Hundred of 2016, Part 2