Corky Siegel performing with Orquestra Experimental de Repertorio, Maestro Jamil Maluf conducting, in São Paulo, Brazil

By David McGee

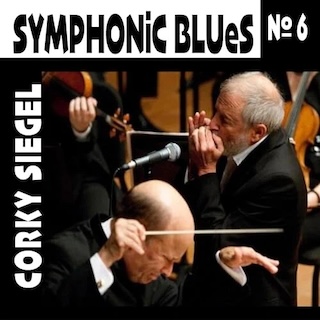

CORKY SIEGEL’S SYMPHONIC BLUES NO. 6

CORKY SIEGEL’S SYMPHONIC BLUES NO. 6

Dawnserly Records

There is an amazing story accompanying the making of Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6. It’s told in Siegel’s own words, written for the included liner booklet and spoken—a mini-audiobook if you will–as the final track on the disc itself. At almost 20 minutes in length it can’t be reprinted here, but in considering the music offered in this latest of bluesman Siegel’s many productive forays into the classical world, a summary of events leading up to this work’s existence would be a good setup.

Symphonic Blues No. 6 actually has its roots in the full sweep of Siegal’s journey as a professional musician, beginning when he and his guitar playing friend Jim Schwall were hired to play a 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. gig at a Chicago tavern, at which they were joined by a bass player and a drummer. Much to their surprise, they found themselves frequently joined by “the blues icons we idolized”—icons on the order of Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Little Walter, et al. “We were embraced by the blues community as soon as we walked in,” Siegal writes, adding that one of those icons was the legendary drummer Sam Lay, who became one of the longest-term members of the Siegel-Schwall Band.

‘Howlin’ for My Darlin’,’ Siegel-Schwall Band, from its self-titled debut album, 1966, for the Vanguard label

While playing at Big John’s in Chicago’s Old Town district, Seigel was approached by a fan suggesting Seigel brings his blues harp along and jam with his band, which happened to be the Chicago Symphony as led by this fan, who was the now-legendary Maestro Seiji Ozawa. “And so in 1966 I was appointed to my role of bringing blues to classical music,” Siegel writes. Siegel’s friend William Russo composed Three Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony, a work specifically for the occasion, and in 1968 the Chicago Symphony premiered it. The next year, 1969, the Russo composition was presented at Lincoln Center by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. It received “the longest and most intense vitriol from an audience that I could imagine. The audience was outraged that hippies, in a blues band, were on-stage as guest soloists.” But at the close of Three Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony the vitriol was supplanted by “a thunderous standing ovation.” Sweet as that was, the New York Times’s esteemed music critic Harold C. Schoenberg hailed the performance and added: “The audience did not merely like it, the audience loved it.”

Movement I: Filisko’s Dream, from Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

“That was my first real experiencer of music’s power to bring people together in harmony. My role in life became harmony: musical harmony, my inner harmony and social harmony. Democracy is the path for social harmony peaceful discourse, where we all have some voice. May we never replace democracy for a short-term idea or wish,” Siegel writes.

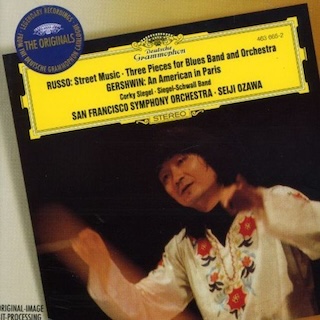

In 1973 Maestro Ozawa and the San Francisco Symphony, with the Siegel-Schwall Band and Corky Siegel as a solo artist, recorded Russo’sThree Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony and Street Music, for the Deutsche Grammaphon label; two years later, 1975, came a commission from Arthur Fiedler, the San Francisco Symphony and the City of San Francisco for Siegel to compose symphonic music. With no skill to speak of in music composition, Seigel was prepared to decline the Fiedler commission but was persuaded to dive in when a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission offered a one-year residency in which to complete the work. The 1976 debut of three new Siegel compositions at the San Francisco Auditorium was not only well received but also produced a commission to work with the National Symphony at Kennedy Center on expanding the original compositions with three more sonatas.

In 1973 Maestro Ozawa and the San Francisco Symphony, with the Siegel-Schwall Band and Corky Siegel as a solo artist, recorded Russo’sThree Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony and Street Music, for the Deutsche Grammaphon label; two years later, 1975, came a commission from Arthur Fiedler, the San Francisco Symphony and the City of San Francisco for Siegel to compose symphonic music. With no skill to speak of in music composition, Seigel was prepared to decline the Fiedler commission but was persuaded to dive in when a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission offered a one-year residency in which to complete the work. The 1976 debut of three new Siegel compositions at the San Francisco Auditorium was not only well received but also produced a commission to work with the National Symphony at Kennedy Center on expanding the original compositions with three more sonatas.

Cut to 1983 and a performance at Chicago’s Grant Park featuring the three sonatas composed for Fiedler and three new sonatas, the end result of which was the idea for Chamber Blues, works for “the healing sound” of a string quartet rather than orchestra: “I could only perform the symphony works when a symphony agreed to do it. Chamber Blues would be portable. I could fit the group easily into a bus—and I would get to drive the bus!”

Movement II: Slow Blues, from Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

There’s more to the concept than portability: “As with the symphonic works, I didn’t want the orchestra or the string quartet to be the back-up band. Nor should the two genres blend into one. I wanted the process to bring the singular compositional aspects of classical music and the blues in an equal partnership where each genre maintains their unique characters and you can hear them, not blending, but working together chasing each other around the room.”

Siegel’s Fiedler commission, two commissions for the Grant Park Symphony and two commissions from Steven Gunzenhauser for the Lancaster Symphony remain unrecorded along with “reams” of unrecorded Chamber Blues and solo material. With community funding, Siegel began recording and releasing material that might not otherwise have seen the light of day, including five Chamber Blues albums to date. Different Voices by Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues was the #18 album in the Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred of 2017 More Different Voices by Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues was a Deep Roots Album of the Year in 2022.

Movement III: Allegro, from Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

Once again, community funding has allowed Symphonic Blues No. 6, otherwise performed live all over the world to great acclaim, to be preserved on disc at last. It’s a different approach to what is arguably the most affecting of all Siegal’s blues-classical hybrids. Seventeen musicians are employed, a dozen being symphonic players, with the Chamber Blues Ensemble members rounding out the lineup (Dr. Jaime Gorgojo, violins; Chihsuan Yang, violins; Jocelyn Butler Shoulders, cellos; Allegra Montenari, cello; and Jeff Yang, violas). From there it really gets interesting: the musicians were all recorded separately, with no reference to the music in any way aside from their own part and tempo markings. “Therefore,” Siegel writes, “each part is a solo part and each performer a soloist throughout the whole work. My style of composition incorporates extreme dynamic markings on almost every note of the part to help ensure expression. Our mixing guru Ken Goerres and the rest of the production team agreed that we didn’t want to try replicate a symphony orchestra. That would be limiting. We just wanted to do whatever we could to create a magnificent sonic experience.” Note: The enthusiastic applause following Movements II and III is a tad deceptive: Symphonic Blues No. 6 was indeed recorded live (in 2008), but for this CD project Siegel had the concert orchestra replaced by the new orchestra assembled specifically for these recording sessions; only the harmonica cadenza and the audience response remains from the original live recording.

CODA for Tabla and Harmonica, featuring Kalyan Pathak from the Chamber Blues Ensemble, as heard on Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

From the swooning strings and dreamy harmonica moans introducing the first of three movements, titled “Filisko’s Dream” (Joe Filisko, “harmonica builder, customizer, repair guru and player…[and] an important figure for Hohner Harmonicas and an important figure in this composition of the first movement, because the harmonica I use for the beginning and ending sections is specially tuned by Filisko himself to what might be called ‘open tuning’ in guitar jargon.”) to the lively interplay between the instruments—so lively and whimsical the instruments begin to comprise a “Carnival of the Animals” gathering—there’s a whole menagerie in this playful opening track, if you want to hear it as such. Camille Saint-Saëns is smiling somewhere, possibly noting a suggestion of his “Lions Royal March” along the way, or “Hens and Roosters,” definitely “The Elephant” rumbling through Movement I. Movement II, “Slow Blues,” does indeed take its time unfolding in haunted atmospherics provided by eerie bassoon formulations until Siegel’s harp enters after two minutes adding moans, stutters and long, lean cries over a lovely wash of strings fashioning a recurring theme, intensity rising and falling, culminating in a jolting crescendo just past the halfway mark of the 7:48 movement, before settling back into a sedate mode that is in turn upended by Siegal’s anguished, scattershot harp effect. Movement III, “Allegro,” reclaims the joyful personality of Movement I in being a jolt of buoyant celebration, the instruments jumping rapturously around the melody with the cellos and contrabass adding muscular gravitas to a party that soon returns to its spirited ways. Following the three movements, Siegel adds a brief (3:20) raga-tinged Coda for Tabla and Harmonica that contains everything from cannon-shot kettle drums to frittering clarinet and bassoon lines as a prologue to Kalyan Pathak’s entrance on tabla and delivering, for lack of a better term, a scat vocal. The Coda that adds a whole other rhythmic and cultural texture to the proceedings, with strings and harmonica engaging the tabla’s propulsive thumps with complementary retorts. “Wrecking Ball Sonata,” a new work for the Chamber Blues Ensemble, features strings and percussion (the tabla is in there) skittering pell-mell around Siegel’s deadpan, Lou Reed-style vocal directed, apparently, at someone with destructive tendencies whose time will surely come (“Hank Williams only hopes/your heart will tell on you,” Siegel laments), The music portion of the album closes with the near-unclassifiable “Opus 11 (for solo violin),” as performed by Dr. Jaime Gorgojo in a style blending folk, blues and Classical elements with tempo and texture changes aplenty over a scintillating five minutes-plus. The CD then closes with “The Story,” Siegel’s audiobook version of the story behind the story of Symphonic Blues No. 6.

‘Wrecking Ball Sonata,’ featuring the Chamber Blues Ensemble, Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

When absorbing the whole of Symphony Blues No, 6, reflect for a moment on how American music has been enriched over time by folk and blues meeting up with classical music. Think of Antonìn Dvorák and George and Ira Gershwin. Think of Florence Price and William Grant Stills. Think of Mark O’Connor and his past 30 years of creating and promoting a new American classical style with a roots music foundation. Listen closely on this album to Movement I: “Filisko’s Dream” and you might hear a fleeting quote from Aaron Copland’s evocation of southwestern wonders. Thus the company in which Siegel, now 81, finds himself on the incredible and fruitful journey that began so inauspiciously when he crossed paths with Seiji Ozawa at Big John’s club in Chicago in 1966. If this be the final recording of Corky Siegel’s remarkable career, then know it as a masterpiece of concept and execution in which elevated technique serves the greater purpose of elevating harmony—musical, inner, social–in the hearts of all who listen.