‘It’s Just Like An Unfinished Diamond’

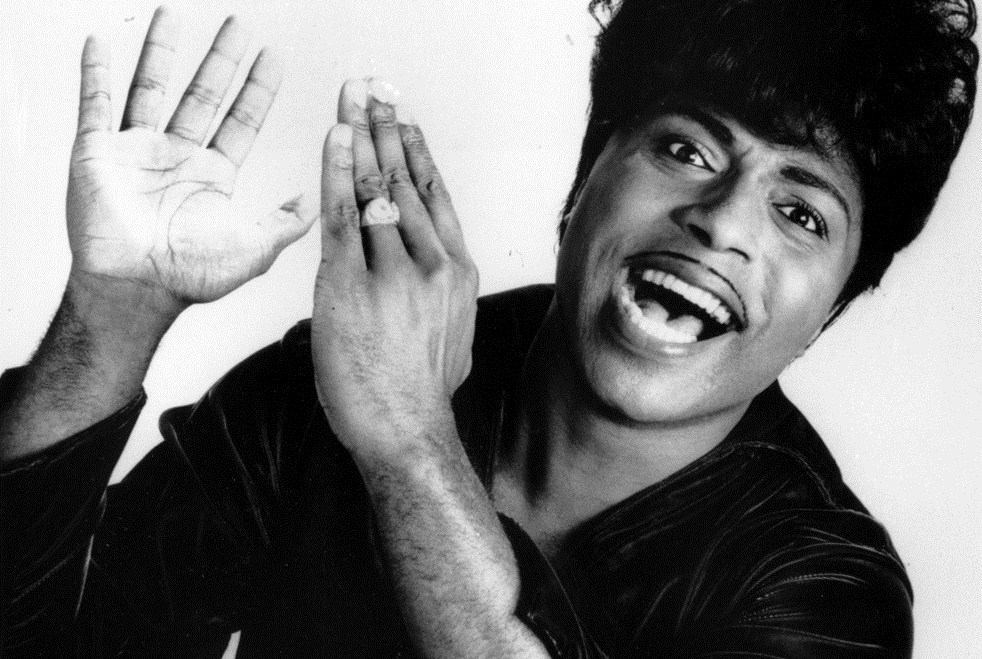

Richard Penniman has at various times, often without prompting, referred to himself as “the originator, the instigator, the facilitator” of rock ‘n’ roll. To varying degrees he’s right on all counts. Rock ‘n’ roll became a musical and cultural force in 1956, with the electrifying emergence of Elvis Presley into the mainstream via “Heartbreak Hotel.” By the time the nascent teen culture was coalescing around “Heartbreak Hotel” and Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” Little Richard had already been a force, with first Specialty single, the riotous “Tutti Frutti,” then nearing the end of its pop chart run after topping out at #17 (it was outdone by Pat Boone’s milquetoast cover, which rose to #12 before stalling), setting the stage for his next full-bore rhythmic assault, “Long Tall Sally,” released in April 1956 and subsequently a chart juggernaut for three full months (and covered by Presley, along with two other Little Richard songs, on his second RCA album). In a two-year period dating from September 1955 to October 1957, Penniman recorded an Olympian body of work for Art Rupe’s Los Angeles-based Specialty label—in addition to the above-named hits, his resume includes “Rip It Up,” “Keep A-Knockin’,” “Lucille,” “Jenny Jenny,” “Good Golly Miss Molly,” and “Ready Teddy”—that not only stood with the best music made by any of the rock ‘n’ roll pioneers but reached across time and the Atlantic Ocean to have a profound influence on the British artists who would revitalize rock ‘n’ roll come 1964, especially Messrs. Lennon and McCartney of The Beatles.

Although he had recorded for multiple labels before Specialty signed him on the strength of rather raw demos he and his band had recorded (“Baby” and “All Night Long”), Richard Penniman finally flowered into the Quasar of Rock at Specialty under the guidance of A&R director Bumps Blackwell, and with a big assist from some of Dave Bartholomew’s ace New Orleans session players. Concord Records, which now owns the Specialty label, is serving up a reminder of this most remarkable and timeless artist’s emergence at the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll with an enhanced CD reissue of his first album, Here’s Little Richard. Not only does it include the original incendiary dozen tracks, but its other features include the two demos that landed Richard his Specialty contract, plus a fascinating nine-minute snippet of a 1997 interview with Art Rupe (who almost never talked to the press), conducted by British music writer Pete Frame for a still-unaired radio documentary. The original album has been in print for years, and the demos have been issued before as well, but the interview with Rupe is certainly a value-added feature, and the disc also includes two vintage videos, screen tests of Richard lip-synching to “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” priceless gems both, both endlessly watchable.

From Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), Little Richard performs his first Specialty hit, ‘Tutti Frutti.’ Introduction by Alan Freed.

Little Richard didn’t arrive at Specialty a fully formed character (well, maybe offstage and in performance he was, but not on record yet). Born December 5, 1932, in Macon, GA, he was singing and playing piano in church at a young age, even as he was absorbing and incorporating into his own repertoire the blues music he had been hearing on the radio. In his early teens he toured the South with medicine shows and various blues bands, and became an acolyte of some formidable regional blues shouters such as Tommy Brown and Billy Wright (a Savoy recording artist who favored pancake makeup, mascara and a multi-level pompadour, and had as much an influence on young Penniman’s appearance as he did his music ). His recording career began in 1951 with some sessions for RCA before he moved to Peacock and recorded solo and with the Tempo Toppers (available now on the Bear Family import disc, The Formative Years 1951-1953 and Rhino’s out of print Shut Up! A Collection of Rare Tracks [1951-1964]); he then appeared uncredited on recordings by Christine Kittrell for the Nashville-based Republic label before returning to Macon to record demos with an early lineup of his band the Upsetters. Those were sent to the Specialty label in Los Angeles, where, having failed to impress Bumps Blackwell, the tape languished for a bit until Richard’s persistence persuaded Art Rupe to give them a listen. Those early recordings and the demos sent to Specialty–“Baby” (a swinging number in a relaxed mode that was the model for one of Richard’s great Specialty B sides, “Miss Ann”) and a solid, midtempo blues ballad titled “All Night Long”)–reveal him to be a forceful vocal personality but not necessarily an original one; in fact, his trilling, nasal tone makes him sound almost exactly like another “Little” artist, namely Little Esther Phillips.

“I was looking for a singer like B.B. King, who was very popular. Frankly, when I got this…at first we didn’t listen to the tape right away. Bumps, who was supposedly screening the tapes, apparently didn’t think much of it, and I can understand why. It was a scratchy tape, it was poorly recorded, it wasn’t a typical good audition tape. And so, if it hadn’t been for Richard’s persistence and aggression, we would never have signed Little Richard. He just kept calling us–from a different town, I’d be getting calls from him. Finally I said, ‘Find that tape,’ and we found it, we listened to it, let’s sign this guy, he sounds like B.B. King to me.’ But of course he isn’t B.B. King.” –Specialty founder Art Rupe, from the interview by Pete Frame included on the reissued Here’s Little Richard.

From Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), Little Richard performs ‘Long Tall Sally’

Rupe sent Richard to New Orleans to record with Bumps Blackwell and a band assembled by Dave Bartholomew, a giant in New Orleans recording history who was then steering the career of Fats Domino, most notably, as producer, bandleader and co-writer. At Cosimo Mattasa’s J&M Recording Studios, Richard was backed by Bartholomew’s A team, which included the formidable drummer Earl Palmer, tenor sax man Lee Allen, the exuberant Professor Longhair-influenced piano pounder Huey Smith, Alvin “Red” Tyler on baritone sax and Justin Adams on guitar, among other stalwarts. (Penniman is no slacker on the piano, but he played in only one key; on the Specialty recordings, Blackwell used not only Huey Smith on the 88s, but also little-known New Orleans session pianists Melvin Dowden and Edward Frank.) Over the course of these sessions, held on September 14 and 15, 1955, Penniman found himself. In a fortuitous moment, Blackwell heard Richard spending a break fooling around with the verses to a bawdy novelty number he performed live, “Tutti Frutti, Good Booty.” Despite its salty lyrics, Blackwell recognized something special about the song and in the way Richard tore through it. He summoned Dorothy LaBostrie, a young songwriter who had been trying to place some material with Blackwell, to do a quick, PG-rated rewrite. The sanitized version was titled simply “Tutti Frutti,” and Penniman kicked it off its recording by shouting the most elegant nonsense lyrics in rock ‘n’ roll history—“Wop-boppa-looma-belop-bomp-bomp”—the band came roaring in and Penniman ascended, declaiming the lyrics in a strong, gritty voice, half speaking, half singing in extolling the charms of gals named Sue and Daisy, who knew just what to do and “almost drive me crazy.” The piano pounded away relentlessly, “Red” Tyler took a booming sax break that was introduced by Richard’s Richard introduced the break with a wild, abandoned, falsetto shout (properly attributed by liner notes author Lee Hildebrand to the influence gospel singers Marion Williams and Alex Bradford had exerted on the Penniman style) that he made his vocal trademark.

“It was more or less [Dave Bartholomew’s] band. He’d done all the backing for Fats Domino. Matter of fact, that’s why I went to New Orleans; I was a fan of Fats’. And the engineer, Cosimo, set them up quite similar, because they both sat at the piano except in the few instances where Richard didn’t. But both of them sat at the piano and sang, so the mic placement and the balance was quite similar. A lot of it had to do with Little Richard. Fats is almost, compared to Richard, phlegmatic; very plodding, very slow, very–just opposite, Little Richard is very dynamic, completely uninhibited, unpredictable, wild. So the band took on the ambience of the vocalist, the soloist. –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview

Little Richard, ‘Rip It Up,’ the original Specialty single (1955, #17 pop, #1 R&B)

Elvis’s cover of ‘Rip It Up,’ the lead track on his second RCA album, Elvis (1957), which also includes covers of Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Ready Teddy’

“Tutti Frutti” was only the start. Richard returned to J&M in February, May, September and October of 1956, backed by most of the musicians Bartholomew had assembled for the “Tutti Frutti” session, although Richard’s own band, The Upsetters, accompanied him on a September 6 session at Master Recorders in Los Angeles (where Richard was doing a screen test for a role in the Tom Ewell-Jayne Mansfield vehicle, The Girl Can’t Help It) on the fiercely rocking “She’s Got It,” which was, oddly, the first Little Richard single to miss the pop chart entirely, although it was a #9 R&B hit. From those sessions came “Long Tall Sally” (#6), “Slippin’ and Slidin’” (#33), “Rip It Up” (#17), “Ready Teddy” (#44) and the relentless “Jenny, Jenny” (on which Richard’s performance is so intense you can hear him gasping for breath at one point), all of which are included on Here’s Little Richard, quite simply one of the best long players in rock ‘n’ roll history. In addition to the classic hits noted above, the album showcases Richard’s emotionally charged ballad singing when he plumbs the pain of betrayal in “Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave”; demonstrates his facility with swing numbers on “Miss Ann” and his ease with novelty numbers on “Oh Why?”, a bluesy outing modeled after the Coasters’ “Framed.”

Little Richard’s original Specialty recording of ‘Jenny, Jenny’ (1957), #10 pop, #2 R&B, included on Here’s Little Richard

Then , in October 1957, not long after Here’s Little Richard was released, the star of the show abruptly quit the rock ‘n’ roll business for the ministry (and gospel music), and stayed away until 1964, when he returned to the Specialty fold but without anywhere near the success he had experienced when in full Qasar mode, at once the most distant and most luminous object in the rock ‘n’ roll universe.

“I don’t know…his story is a good characterization of it. I don’t know the real reason. I suspect the reason was other than what is typical Richard other than what he reveals. But he had found religion, he says. He was in Australia on tour and the Sputnik reached its lowest point in that area, and he saw that as a sign that it was Armageddon, the world was coming to an end. Supposedly he took off all his jewelry and threw ‘em into the water, got saved or converted, and he wouldn’t record the Devil’s music anymore–and he wouldn’t work for the Devil anymore either. (laughs) That was Little Richard. We did everything trying to get him to come back, including withholding his royalties. We said, ‘When you comply with your contract, we’ll comply with yours, the money’s here, it’s yours.’ We ended up having to sue him, he counter-sued, and he went his merry way, and we bought out the balance of his contract. It was very difficult, because Richard could have blown his nose and we could have recorded it and sold it! You know, we had the demand. We put out records I never would have ordinarily put out, including splicing together where the timing on it is atrocious. I can’t stand someone not keeping a beat. Even talking about it bothers me now.” –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview.

From Here’s Little Richard, a non-single album track, ‘Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave’

As he says above, Art Rupe continued to release Little Richard recordings he had in the can when the artist bugged out and fled into the ministry, but Richard’s Top 40 run was at an end by mid-1958, when “Ooh! My Soul” peaked at Number 31. The ledger shows, though, Penniman not nearly as dominant a pop singles artist as his peers: he never had a #1 single, his highest chart entry was “Long Tall Sally” at #6, and he notched only three Top 10 singles during the Specialty years. No matter—the music and the man made an incalculable impact, culturally and musically, to render mere chart numbers, or lack thereof, a moot point. Much of his Specialty work is in print, and to survey it is to be awed by the power, passion and depth of Richard’s artistry. A three-disc box set of everything he cut at Specialty is, unfortunately, out of print and going for upwards of $130 at Amazon, but for a solid single-disc overview, Here’s Little Richard and 1991’s The Georgia Peach really cover the waterfront in most respects. Post-Specialty he made one great album, 1970’s The Rill Thing, when he was signed to Reprise. Recorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, The Rill Thing is the real deal Richard Penniman, often goosebump-inducing in its intensity: its irresistible stomper “Freedom Blues” is a successful foray into socially conscious lyrics; Travis Wammack’s “Greenwood, Mississippi,” is a bruising southern soul workout; the reckless abandon he brings to Esquerita’s “Dew Drop Inn” along with his ferocious keyboard attack recalls the glory days of Specialty; an Allman-style blues rocker, “Two Time Loser,” built on a recurring triplet guitar riff, finds Richard at his loosest vocally, wailing unencumbered; and he turns Hank Williams’s career launching monument, “Lovesick Blues,” inside out, reworking it as a funky, Memphis soul-style workout.

‘Freedom Blues,’ Little Richard, from 1970’s The Rill Thing, recorded in Muscle Shoals

Little Richard is a real enigma. If he would have taken direction a little better, if he would have been disciplined, he would have probably been….I don’t know where he could have been. He would have been almost what Frank Sinatra is in the pop field. Little Richard can dominate an audience, he can control an audience, he can upstage any act. He’s unpredictable but he’s got an enormous amount of energy, a tremendous amount of natural talent. I’ve met a lot of performers–Louis Armstrong, Nat Cole, etc.–Little Richard had–has–raw talent. It’s just like an unfinished diamond. I have a lot of admiration for Richard. The real classic of Little Richard would have been his singing old standards, if he had listened to us. You oughta listen to him doing ‘Baby Face.’ He could have put so much feeling doing the old standards that he could be performing today in Las Vegas or anywhere. He was a real interpreter of lyrics, if you could understand them. He’s really excellent. –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview