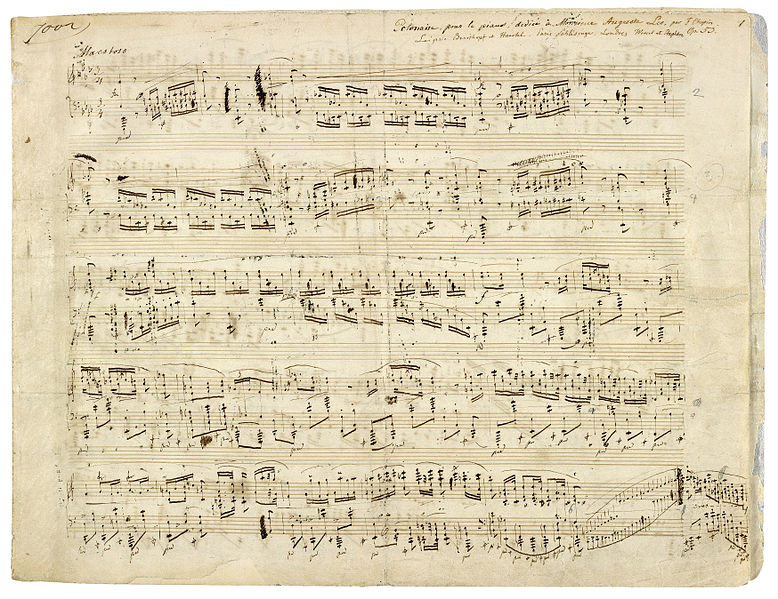

Autographed partiture by the Polish composer Frédéric Chopin of his Polonaise Op. 53 in A flat major for piano, 1842.

Nature does not design like art, however realistic she may be. She has caprices, inconsequences, probably not real, but very mysterious. Art only rectifies these inconsequences, because it is too limited to reproduce them. Chopin was a resume of these inconsequences which God alone can allow Himself to create, and which have their particular logic. He was modest on principle, gentle by habit, but he was imperious by instinct and full of a legitimate pride which was unconscious of itself. Hence arose sufferings which he did not reason and which did not fix themselves on a determined object. —George Sand in “The Story of My Life”

Ed. Note: Elbert Green Hubbard (June 19, 1856-May 7, 1915) was an American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher. Raised in Hudson, Illinois, he met early success as a traveling salesman with the Larkin soap company. Today Hubbard is mostly known as the founder of the Roycroft artisan community in East Aurora, New York, an influential exponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

His masterwork was a 14-volume collection of biographical sketches, published between 1895 and 1910, under the title Little Journeys to the Homes of Good Men and Great. Its 14 volumes include: (v. 1) To the homes of good men and great; (v. 2) To the homes of famous women; (v. 3) To the homes of American statesmen; (v. 4) To the homes of eminent painters; (v. 5) To the homes of English authors; (v. 6) To the homes of eminent artists; (v. 7) To the homes of eminent orators; (v. 8) To the homes of great philosophers; (v. 9) To the homes of great reformers; (v. 10) To the homes of great teachers; (v. 11) To the homes of great business men; (v. 12) To the homes of great scientists; (v. 13) To the homes of great lovers; (v. 14) To the homes of great musicians.

The October 2013 edition of Deep Roots featured Hubbard’s chapter on Mozart from Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Musicians. This month we return to Hubbard’s tome for a fascinating chapter on Frédéric Chopin, whom the author links to American novelist Stephen Crane, describing the latter as “a reincarnation” of the great Polish composer. Asserts Hubbard: Both were small in stature, slight, fair-haired, and of that sensitive, acute, receptive temperament—capable of highest joy and keyed for exquisite pain. Haunted with the prophetic vision of quick-coming death, and with the hectic desire to get their work done, they often toiled the night away and were surprised by the rays of the rising sun. Both were shrinking yet proud, shy but bold, with a tenderness and a feminine longing for love that earth could not requite. At times mad gaiety, that ill-masked a breaking heart, took the reins, and the spirits of children just out of school seemed to hold the road. At other times—and this was the prevailing mood—the manner was one of placid, patient, calm and smooth, unruffled hope; but back and behind all was a dynamo of energy, a brooding melancholy of unrest, and the crouching world-sorrow that would not down. … Chopin reached sublimity through sweet sounds; Crane attained the same heights through the sense of sight and words that symboled color, shapes and scenes. In each the distinguishing feature is the intense imagination and active sympathy.

Do not be misled, dear readers. Hubbard’s focus is on Chopin, and his insights and observations remain compelling nearly a century after they were first revealed in print.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZGi49Bnghs

Vladimir Horowitz performs Chopin’s Polonaise Op. 53 in A flat major

aybe I am all wrong about it, yet I can not help believing that the spirit of man will live again somewhere in a better world than ours. Fenelon says, “Justice demands another life in order to make good the inequalities of this.” Astronomers prophesy the existence of stars long before they can see them. They know where they ought to be, and training their telescopes in that direction they wait, knowing they will find.

Materially, no one can imagine anything more beautiful than this earth, for the simple reason that we can not imagine anything we have not seen; we may make new combinations, but the whole is all made up of parts of things with which we are familiar. This great green earth out of which we have sprung, of which we are a part, that supports our bodies, and to which our bodies must return to repay the loan, is very, very beautiful.

But the spirit of man is not fully at home here; as we grow in soul and intellect, we hear, and hear again, a voice which says, “Arise and get thee hence, for this is not thy rest.” And the greater and nobler and more sublime the spirit, the more constant the discontent. Discontent may come from various causes, so it will not do to assume that the discontented are always the pure in heart, but it is a fact that the wise and excellent have all known the meaning of world-weariness. The more you study and appreciate this life, the more sure you are that this is not all. You pillow your head upon Mother Earth, listen to her heart-throb, and even as your spirit is filled with the love of her, your gladness is half-pain and there comes to you a joy that hurts.

To look upon the most exalted forms of beauty, such as a sunset at sea, the coming of a storm on the prairie, the shadowy silence of the desert, or the sublime majesty of the mountains, begets a sense of sadness, an increasing loneliness.

Evgeny Kissin, Chopin Waltz Op. 64 n.2

It is not enough to say that man encroaches on man so that we are really deprived of our freedom, that civilization is caused by a bacillus, and that from a natural condition we have gotten into a hurly-burly where rivalry is rife—all this may be true, but beyond and outside of all this there is no physical environment in way of plenty which earth can supply, that will give the tired soul peace. They are the happiest who have the least; and the fable of the stricken king and the shirtless beggar contains the germ of truth. The wise hold all earthly ties very lightly—they are stripping for eternity.

World-weariness is only a desire for a better spiritual condition. There is more to be written on this subject of world-pain—to exhaust the theme would require a book. And certain it is that I have no wish to say the final word on any topic. The gentle reader has certain rights, and among these is the privilege of summing up the case. But the fact holds that world-pain is a form of desire. All desires are just, proper and right; and their gratification is the means by which Nature supplies us that which we need. Desire not only causes us to seek that which we need, but is a form of attraction by which the good is brought to us, just as the ameba creates a swirl in the waters that brings its food within reach. Every desire in Nature has a fixed, definite purpose in the Divine Economy, and every desire has its proper gratification. If we desire the friendship of a certain person, it is because that person has certain soul-qualities that we do not possess, and which complement our own. Through desire do we come into possession of our own; by submitting to its beckonings we add cubits to our stature; and we also give out to others our own attributes, without becoming poorer, for soul is not limited.

All Nature is a symbol of spirit, so I believe that somewhere there must be a proper gratification for this mysterious nostalgia of the soul. The Eternal Unities require a condition where men and women will live to love, and not to sorrow; where the tyranny of things hated shall not ever prevail, nor that for which the heart yearns turn to ashes at our touch.

believe Stevie is not quite at home here—he’ll not remain so very long,” said a woman to me in Eighteen Hundred Ninety-five. Five years have gone by, and recently the cable flashed the news that Stephen Crane was dead.

Dead at twenty-nine, with ten books to his credit, two of them good, which is two good books more than most of us scribblers will ever write. Yes, Stephen Crane wrote two things that are immortal. “The Red Badge of Courage” is the strongest, most vivid work of imagination ever fished from an ink-pot by an American.

“Men who write from the imagination are helpless when in presence of the fact,” said James Russell Lowell. In answer to which I’ll point you “The Open Boat,” the sternest, creepiest bit of realism ever penned, and Stevie was in the boat.

American critics honored Stephen Crane with more ridicule, abuse and unkind comment than was bestowed on any other writer of his time. Possibly the vagueness, and the loose, unsleeked quality of his work invited the gibes, jeers, and the loud laughter that tokens the vacant mind; yet as half-apology for the critics we might say that scathing criticism never killed good work; and this is true, but it sometimes has killed the man.

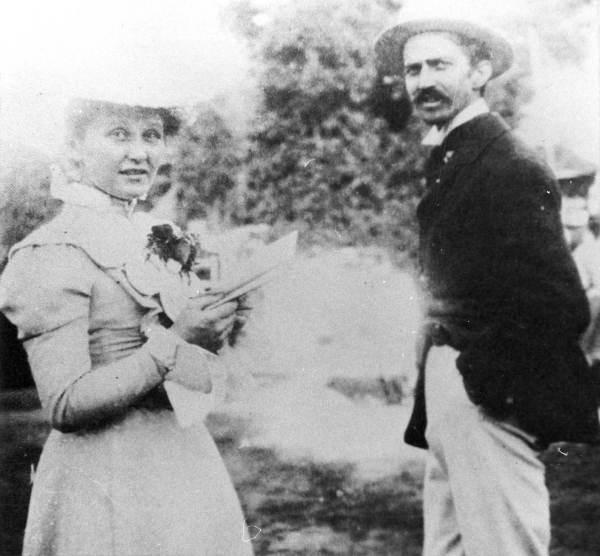

Cora and Stephen Crane, circa 1896 (Metro Jacksonville Photo Archives): ‘Chopin reached sublimity through sweet sounds,’ wrote Elbert Hubbard. ‘Crane attained the same heights through the sense of sight and words that symboled color, shapes and scenes. In each the distinguishing feature is the intense imagination and active sympathy.’

Stephen Crane never answered back, nor made explanation, but that he was stung by the continued efforts of the press to laugh him down, I am very sure.

The lack of appreciation at home caused him to shake the dust of America from his feet and take up his abode across the sea, where his genius was being recognized, and where strong men stretched out sinewy hands of welcome, and words of appreciation were heard, instead of silly, insulting parody. In passing, it is well to note that the five strongest writers of America had their passports to greatness viséed in England before they were granted recognition at home. I refer to Walt Whitman, Thoreau, Emerson, Poe and Stephen Crane.

Stevie did not know he cared for approbation, but his constant refusal to read what the newspapers said about him was proof that he did. He boycotted the tribe of Romeike, because he knew that nine clippings out of every ten would be unkind, and his sensitive soul shrank from the pin-pricks.

Contemporary estimates are usually wrong, and Crane is only another of the long list of men of genius to whom Fame brings a wreath and finds her poet dead.

Stephen Crane was a reincarnation of Frederic Chopin. Both were small in stature, slight, fair-haired, and of that sensitive, acute, receptive temperament—capable of highest joy and keyed for exquisite pain. Haunted with the prophetic vision of quick-coming death, and with the hectic desire to get their work done, they often toiled the night away and were surprised by the rays of the rising sun. Both were shrinking yet proud, shy but bold, with a tenderness and a feminine longing for love that earth could not requite. At times mad gaiety, that ill-masked a breaking heart, took the reins, and the spirits of children just out of school seemed to hold the road. At other times—and this was the prevailing mood—the manner was one of placid, patient, calm and smooth, unruffled hope; but back and behind all was a dynamo of energy, a brooding melancholy of unrest, and the crouching world-sorrow that would not down.

Chopin reached sublimity through sweet sounds; Crane attained the same heights through the sense of sight and words that symboled color, shapes and scenes. In each the distinguishing feature is the intense imagination and active sympathy. Knowledge consists in a sense of values—of distinguishing this from that, for truth lies in the mass. The delicate nuances of Chopin’s music have never been equaled by another composer; every note is cryptic, every sound a symbol. And yet it is dance-music, too, but still it tells its story of baffled hope and stifled desire—the tragedy of Poland in sweet sounds.

Stephen Crane was an artist in his ability to convey the feeling by just the right word, or a word misplaced, like a lady’s dress in disarray, or a hat askew. This daring quality marks everything he wrote. The recognition that language is fluid, and at best only an expedient, flavors all his work. He makes no fetish of a grammar—if grammar gets in the way, so much the worse for the grammar. All is packed with color, and charged with feeling, yet the work is usually quiet in quality and modest in manner.

Art is born of heart, not head; and so it seems to me that the work of these men whose names I have somewhat arbitrarily linked, will live. Each sowed in sorrow and reaped in grief. They were tender, kind, gentle, with a capacity for love that passes the love of woman. They were each indifferent to the proprieties, very much as children are. They lived in cloister-like retirement, hidden from the public gaze, or wandered unnoticed and unknown. They founded no schools, delivered no public addresses, and in their own day made small impress on the times. Both were sublimely indifferent to what had been said and done—the term precedent not being found within the covers of their bright lexicon of words. In the nature of each was a goodly trace of peroxide of iron that often manifested itself in the man’s work.

The faults in each spring from an intense personality, uncolored by the surroundings, and such faults in such men are virtues.

They belong to that elect few who have built for the centuries. The influence of Chopin, beyond that of other composers, is alive today, and moves unconsciously, but profoundly, every music-maker; the seemingly careless style of Crane is really lapidaric, and is helping to file the fetters from every writer who has ideas plus, and thoughts that burn.

Mother Nature in giving out energy gives each man about an equal portion. But that ability to throw the weight with the blow, to concentrate the soul in a sonnet, to focus force in a single effort, is the possession of God’s Chosen Few. Chopin put his affection, his patriotism, his wrath, his hope, and his heroism into his music—as if the song of all the forest birds could be secured, sealed and saved for us!

he father of Chopin was a Frenchman who went up to Poland seeking gain and adventure. He became a soldier under Kosciusko and arose to rank of Captain. He found such favor with the nobility by his gracious ways that he became a teacher of French in the family of Count Frederic Skarbek. In the family group was a fair young dependent of nervous temperament—slight, active, gentle and intelligent. She was descendent from a line of aristocrats, but in a country where revolutions have been known to begin and end before breakfast, titles stand for little.

Nicholas Chopin, ex-soldier, teacher of French and Deportment, married this fine young girl, and they lived in one of Count Skarbek’s straw-thatched cottages at the little village of Zelazowa-Wola, twenty-nine miles from Warsaw. Here it was that Frederic Chopin was born, in Eighteen Hundred Nine—that memorable year when Destiny sent a flight of great souls to the planet Earth.

The country was bleak and battle-scarred; it had been drained of its men and treasure, and served as a dueling-ground and the place of skulls for kings and such riffraff who have polluted this fair world with their boastings of a divine power.

The struggle of Poland to free herself from the grip of the imperial succubi has generated an atmosphere of ultramarine, so we view the little land of patriots (and fanatics) through a mist of melancholy. The history of Poland is written in blood and tears.

Go ask John Sobieski, who saw his father hanged by order of Ferdinand Maximilian, and child though he was, realized that banishment was the fate of himself and mother; and then ten years after, himself, stood death-guard over this same Maximilian in Mexico, and told that tyrant the story of his life, and shook hands with him, calling it quits, ere the bandage was tied over the eyes of the ex-dictator and the sunlight shut out forever.

Go ask John Sobieski!

Jimmy Page, Chopin, Prelude in E minor: Op. 28 n.4

The woes of Poland have produced strange men. Under such rule as she has known relentless hate springs up in otherwise gracious hearts from the scattered dragons’ teeth; and in other natures, where there is not quite so much of the motive temperament, a deep strain of sorrow and religious melancholy finds expression. The exquisite sensibility, delicate insight, proud reserve and brooding world-sorrow of Frederic Chopin were the inheritance of mother to son. This mother’s mind was saturated with the wrongs her people had endured: she herself had suffered every contumely, for where chance had caused fact to falter, imagination had filled the void.

It is easy to say that Chopin’s was an abnormal nature, and of course it was, but when disease divides this world from another only by the thinnest veil, the mind has been known to see things with a clearness and vividness never before attained. With Chopin the strands of life were often taut to the breaking-point, but ere they snapped, their vibration gave forth to us some exquisite harmonies.

Curiously enough, this power to see and do is often the possession of dying men. The life flares up in a flame before it goes out forever. The passion of the consumptive Camille, as portrayed by Dumas, is typical—no healthy woman ever loved with that same intense, eager and almost vindictive desire. It was a race with Death.

Perfect health brings unconsciousness of body, and disease that almost relieves the spirit of this weight of flesh produces the same results. Again we have the Law of Antithesis.

That such a youth as Frederic Chopin should seek in music a surcease from his world-sorrow is very natural. A stricken people turns to music; it forms a necessary part of all religious observance, and the dirge of mourners, the wail of the “keener,” and the songs of the banshee evolve naturally into being wherever the heart is sore oppressed. It was the slave-songs that made slavery bearable; and in the long ago, exiles in Babylon found a solemn joy by singing the songs of Zion. Chopin drank in the songs of Poland with his mother’s milk, and while yet a child began to give them voice in his own way.

In the meantime his father’s fortunes had mended a bit, and the family had moved to Warsaw, where Nicholas Chopin was Professor of Languages at the Lyceum. The title of the office fills the mouth in a very satisfying way, but the emoluments attached hardly afforded such a gratification.

In Warsaw there was much misery, for the plunderer had worked conscription and seizure to its furthest limit. Want and destitution were on every hand, but still this brave people maintained their University and clung to its traditions. The family of the Professor of Languages consisted of himself, wife, three daughters and the son Frederic. Their income for several years was not over fifteen dollars a month, but still they managed to maintain an appearance of decency, and by the help of the public library, the free museum and the open-air concerts, they kept abreast of the times in literature, art and music.

There was absolute economy required, every particle of food was saved, and when cast-off dresses were sent from the home of the Count it was a godsend for the mother and girls, who measured and patched and pieced, making garments for themselves, and for Frederic as well; so while their raiment was not gaudy nor expressed in fancy, it served.

Chopin once said to George Sand, “I never can think of my mother without her knitting-needles!” And George Sand has recorded, “Frederic never had but one passion and that was his mother.” Into all of her knitting this mother’s flying needles worked much love. The entire household was one of mutual service, and gentle, trusting affection. The weekly letters of Chopin to his mother from Paris, and the cold sweat on his forehead at the thought of his parents knowing of his relationship with George Sand, are credit-marks to his character. There is a sweet recompense in mutual deprivation where trials and difficulties only serve to cement the affections; and who shall say how much the wondrous blending of strength and delicacy in the music of Chopin is due to the memory of those early days of toil and trial, of strength and forbearance, of hope and love?

Wladyslaw Szpilman, whose life story was the subject of Roman Polanski’s Oscar winning 2000 film The Pianist, performs Chopin’s Nocturne in C sharp, Op. 20

To be born into such a family is a great blessing. The value of the environment is shown in that all three of the sisters became distinguished in literature. Two of them married men of intellect, wealth and worth, and through the collaboration of these sisters, books were produced that did for the plain people of Poland what Harriet Martineau’s books on sociology did for the people of England. Frederic played and practised at the Lyceum where his father taught, and the ambition of his parents was that he should grow up and take the place of Professor of Music in the Lyceum. Adalbert Zevyny, one of the leading pianists in the city, became attracted to the boy and took him as a pupil, without pay.

The teacher soon became a little boastful of his precocious pupil, and when there came a public concert for the benefit of the poor, we find reference made to Chopin thus, “A child not yet eight years of age played, and connoisseurs say he promises to replace Mozart.” In reality the boy was nearer twelve than eight, but his size and looks suggested to the management the idea of plagiarizing, in advance, our honored countryman, Phineas T. Barnum. Hence the announcement on the programs.

But now the nobility of the neighborhood began to send carriages for the fair-haired lad, so he could play for their invited guests. Then came snug little honorariums that soon replaced his patched-up wardrobe for something more fashionable.

Frederic took all the applause quite as a matter of course, and on one occasion, after he had played divinely, he asked a proud lady this question, “How do you like my new collar?”

He was to the manner born, and the gentle blood of his mother formed him as a fit companion for aristocrats.

These occasional musicales at the houses of the great made money matters easier, and Frederic began to take lessons from Joseph Elsner, who taught him the science of composition, and introduced him into the deeper mysteries of music-making. Elsner, it was, more than any other man, who forced the truth upon Chopin that he must play to satisfy himself, and in composition be his own most exacting critic. In other words, Elsner developed and strengthened in Chopin the artistic conscience—that impulse which causes an artist to scorn doing anything save his best.

From little excursions to neighboring towns and country houses about Warsaw, Chopin now ventured farther away from home, chaperoned by his friend, Prince Radziwill. He visited Berlin, Venice, Prague, Heidelberg, and mingled on an absolute equality with the nobility. If they had titles, he had talents. And his talents often made their decorations sing small.

His modesty was witching, and while in public concerts his playing was not pronounced enough to capture the gallery, yet in small gatherings he won all hearts, and the fact that he played his own compositions made him an added object of enthusiasm to the elect. Chopin arrived in Paris when he was twenty-two years of age. It was not his intention to remain more than a few weeks, but Paris was to be his home for eighteen years—and then Pere la Chaise.

woman who beholds her thirtieth birthday in sight, and girlhood gone, is approaching a climacteric in her career. Flaubert has named twenty-nine as the eventful year in the life of woman, and thirty-three for men. Every normal woman craves love and tenderness—these are her God-given right. If they have not come to her by the time the bloom is fading from her cheeks, there is danger of her reaching out and clutching for them. The strongest instinct in young girls is self-protection—they fight on the defensive. But at thirty, women have been known to grow a trifle anxious, just as did the Sabine women who dispatched a messenger to the Romans asking this question, “How soon does the program begin?”

And thus are conditions reversed, for it is the youth of twenty or so who seeks conquest with fiery soul. Alexander was only nineteen when he sighed for more worlds to conquer. He didn’t have to wait long before he found that this one had conquered him. Youth considers itself immortal, and its powers without limit, but as a man approaches thirty he grows economical of his resources and parsimonious of his emotions. Men of thirty, or so, are apt to be coy.

And so one might say that it is around thirty that for the first time the man and the woman meet on an equality, without sham, shame or pretense. Before that time the average woman abounds in affectation and untruth; the man is absurdly aggressive and full of foolish flattery.

As to the question, “Should women propose?” the answer is, “Yes, certainly, and they do when they are twenty-nine.”

Amantine-Lucille-Aurore Dupin saw her thirtieth birthday looming on the horizon of her life. Nine years before she had been married to an ex-army-officer, who dyed his whiskers purple. Aurore had been a dutiful wife, intent for the first few years on filling her husband’s heart and home with joy. She had failed in this, and the proof of failure lay in that he much preferred his dogs, guns and horses to her society. For days he would absent himself on his hunting excursions, and at home he did not have the tact to hide the fact that he was awfully bored.

Thackeray, once for all, has given us a picture of the heavy dragoon with a soul for dogs—one to whom all music, save the bay of a fox-hound, makes its appeal in vain. Aurore detested dogs for dogs’ sake, yet she rode horses astride with a daring that made her husband’s bloodshot eyes bulge in alarm. He didn’t much care how fast and hard she rode at the fences and over the ditches, but he was supposed to follow her, and this he did not care to do. He had reached an age when a man is mindful of the lime in his bones, and his ‘cross-country riding was mostly a matter of memory and imagination, and best done around the convivial table.

Aurore was putting him to a test, that’s all. She was proving to him that she could meet him on his own preserve, give him choice of weapons, and make him cry for mercy.

Chopin and George Sand: ‘Chopin was sick and friendless, and Madame Dupine, knowing his worth to the art world, succored him—nursing him as a Sister of Charity might, sacrificing herself, and even risking her reputation in order to restore him to life and health.

Her bent was literature, with music, science and art as side-lines. She read Montaigne, Rochefoucald, Racine and Moliere, and a modern by the name of Alfred de Musset, and quoted her authors at inconvenient times. She flashed quotations and epigrams upon the doughty dragoon in a way he could neither fend nor parry. At other times she was deeply religious and tearfully penitent.

In fact, she was living on a skimped allowance of love, and had never received the attention that a good woman deserves. Her chains were galling her. She sighed for Paris—forty miles away—Paris and a career.

The epigrams were coming faster, shot in a sort of frenzy and fever. And when she asked her liege for leave to go to Paris, he granted her prayer, and agreed to give her ten dollars a week allowance.

She grabbed at the offer, and he bade her Godspeed and good riddance.

So leaving her two children behind, until such a time as she could provide a home for them, with scanty luggage and light heart and purse, she started away.

Other women have gone up to Paris from country towns, too, and the chances are as one to ten thousand that the maelstrom will sweep them into hades.

But Madame Dupine was different—in two years she had won her way to literary fame, and was commanding the jealous admiration of the best writers of Paris. Her first work was a collaboration with Jules Sandeau in a novel. Every woman who ever wrote well began by collaborating with a man. Sandeau had formerly come from Nohant, and how much he had to do with Madame Dupine’s breaking loose from her homes-ties no one knows. Anyway, the second novel was written by the Madame alone, and as a tribute to her friend the name “George Sand” was placed upon the title-page as author. Jules Sandeau, all-’round hack-writer and critic, was greatly pleased by the compliment of having his name anglicized and printed on the title-page of “Indiana,” but later he was not so proud of it. George Sand soon proved herself to be a bigger man than Sandeau.

She was not handsome, either in face or in form. She was inclined to be stout—was rather short—and her complexion olive. But she lured with her eyes—great sphinx-like eyes of hazel-brown—that looked men through and through. Liszt has told us that “she had eyes like a cow,” which is not so bad as Thomas Carlyle’s remark that George Eliot had a face like a horse. George Sand was silent when other women talked, and her look told in a half-proud, half-sad way that she knew all they knew, and all she herself knew beside.

Without going into the issue as to what George Sand was not, let us frankly admit that pain, deprivation, misunderstanding and maternity had taught her many things not found in books, and that she looked at Fate out of her wide-open eyes with a gaze that did not blink. She was wise beyond the lot of women. I was just going to say she was a genius, but I remember the remark of the De Goncourts to the effect that, “There are no women of genius—women of genius are men.” Possibly the point could be covered by saying George Sand had a man’s head and a woman’s heart.

Women did not like her, yet what other woman was ever so honored by woman as was George Sand in those two matchless sonnets addressed to her by Elizabeth Barrett Browning?

Sand and Chopin: ‘Your playing makes me live over again every pain that has ever wrung my heart; and every joy, too, that I have ever known is mine again.’

The amazing energy of George Sand, her finely flowing sentences—all charged with daring satire and insight into the heart of things—made her work sought by readers and publishers. Her pen brought her all the money she needed; and she had secured a divorce from “That Man,” and now had her two children with her in Paris. That she could do her literary work and still attend to her manifold social duties must ever mark her as a phenomenon. She was no mere adventuress. That she was systematic, orderly and abstemious in her habits must go without saying, otherwise her vitality would not have held out and allowed her to attend the funerals of nearly all her retainers.

In throwing overboard the Grub Street Sandeau for Franz Liszt, Madame Dupine certainly showed discrimination; but in retaining the name of “Sand,” she paid a delicate compliment to the man who first introduced her to the world of art. Liszt was too strong a man to remain long captive—he refused to supply the doglike and abject devotion which Aurore always demanded. Then came Michael de Bourges the learned counsel, Calmatto the mezzotinter, Delacroix the artist, De Musset the poet, and Chopin the musician.

It was in the year Eighteen Hundred Thirty-nine, that Chopin and Sand first met at a parlor musicale, where Chopin was taken by Liszt, half against his will, simply because George Sand was to be there.

Chopin did not want to meet her.

All Paris had rung with the story of how she and De Musset had gone together to Venice, and then in less than a year had quarreled and separated. Both made good copy of the “poetic interval,” as George Sand called it. Chopin was not a stickler for conventionalities, but George Sand’s history, for him, proved her to be coarse and devoid of all the finer feeling that we prize in women.

Chopin had no fear of her—not he—only he did not care to add to his circle of acquaintances one so lacking in inward grace and delicacy.

He played at the musicale—it was all very informal—and George Sand pushed her way up through the throng that stood about the piano and looked at the handsome boy as he played—she looked at him with her big, hazel, cow eyes, steadfastly, yearningly, and he glancing up, saw the eyes were filled with tears.

When the playing ceased, she still stood looking at the great musician, and then she leaned over the piano and whispered, “Your playing makes me live over again every pain that has ever wrung my heart; and every joy, too, that I have ever known is mine again.”

ter their first meeting, when Chopin played at a musicale, George Sand was apt to be there too—they often came together. She was five years older than he, and looked fifteen, for his slight figure and delicate, boyish face gave him the appearance of youth unto the very last. In letters to Madame Mariana, George Sand often refers to Chopin as “My Little One,” and when some one spoke of him as “The Chopinetto,” the name seemed to stick.

That she was the man in the partnership is very evident. He really needed some one to look after him, provide mustard-plasters and run for the camphor and hot-water bottle. He was the one who did the weeping and pouting, and had the “nerves” and made the scenes; while she, on such occasions, would viciously roll a cigarette, swear under her breath, console and pooh-pooh.

Liszt has told us how, on one occasion, she had gone out at night for a storm-walk, and Chopin, being too ill, or disinclined to go, remained at home. Upon her return she found him in a conniption, he having composed a prelude to ward off an attack of cold feet, and was now ready to scream through fear that something had happened to her. As she entered the door he arose, staggered and fell before her in a fainting fit.

A whole literature has grown up around the relations of Chopin and George Sand, and the lady in the case has, herself, set forth her brief with painstaking detail in her “Histoire de Ma Vie.” With De Musset, George Sand had to reckon on dealing with a writing man, and his accounts of “The Little White Blackbird” had taught her caution. Thereafter she abjured the litterateurs, excepting when in her old age she allowed Gustave Flaubert to come within her sacred circle—but her friendship with Flaubert was placidly platonic, as all the world knows. And so were her relations with Chopin, provided we accept her version as gospel fact.

Claudio Arrau, Chopin, Fantasie Impromptu Op. 66 in C sharp minor

George Sand lacked the frankness of Rousseau; but I think we should be willing to accept the lady’s statements, for she was present and really the only one in possession of the facts, excepting, of course, Chopin, and he was not a writer. He could express himself only at the keyboard, and the piano is no graphophone, for which let us all be duly thankful. So we are without Chopin’s side of the story. We, however, have some vigorous writing by a man by the name of Hadow.

Mr. Hadow enters the lists panoplied with facts, and declares that the friendship was strictly platonic, being on the woman’s side of a purely maternal order. Chopin was sick and friendless, and Madame Dudevant, knowing his worth to the art world, succored him—nursing him as a Sister of Charity might, sacrificing herself, and even risking her reputation in order to restore him to life and health.

And this view of the case I am quite willing to accept. Mr. Hadow is no joker, like that man who has recently written an appreciation of Xantippe, showing that the wife of Socrates was one of the most patient women who ever lived, and only at times resorted to heroic means in order to drive her husband out into the world of thought. She willingly sacrificed her own good name that another might have literary life.

Hadow has gotten all the facts together and then dispassionately drawn his conclusions; and these conclusions are eminently complimentary to all parties concerned.

It was only a few months after Chopin met George Sand that he was attacked with a peculiar hacking cough. His friends were sure it was consumption, and a leading physician gave it as his opinion that if the patient spent the approaching Winter in Paris, it would be death in March.

The facts being brought to the notice of George Sand, she had but one thought—to save the life of this young man. He was too ill to decide what was best to do, and was never able by temperament to take the initiative, anyway, so this strong and capable woman, forgetful of self and her own interests, made all the arrangements and took him to the Isle of Majorca in the Mediterranean Sea. There she cared for him alone as she might for a babe, for six long, weary months. They lived in the cells of an old monastery at Valdemosa, away up on the mountainside overlooking the sea. Here where the roses bloomed the whole year through, surrounded by groves of orange-trees, shut in by vines and flowers, with no society save that of the sacristan and an aged woman servant, she nursed the death-stricken man back to life and hope.

To better encourage him she sent for and surprised him with his piano, which had to be carried up the mountain on the backs of mules. In the quiet cloisters she cared for him with motherly tenderness, and there he learned again to awake the slumbering echoes with divine music. Several of his best pieces were composed at Majorca during his convalescence, where the soft semi-tropical breeze laved his cheek, the birds warbled him their sweetest carols, and away down below, the sea, mother of all, sang her ceaseless lullaby. When they returned to France the following Spring, M. Dudevant had accommodatingly vacated the family residence at Nohant in favor of his wife. It was here she took the convalescent Chopin. He was charmed with the rambling old house, its walled-in gardens with their arbors of clustering grapes, and the green meadows stretching down to the water’s edge, where the little river ran its way to the ocean.

Back of the house was a great forest of mighty trees, beneath whose thick shade the sun’s rays never entered, and a half-mile away arose the spire of the village church. There were no neighbors, save a cheery old priest, and the simple villagers who made respectful obeisance as they passed. Here it was that Matthew Arnold came to pay his tribute to genius, also Liszt and the fair Countess d’Agoult, Delacroix, Renan, Lamennais, Lamartine, and so many others of the great and excellent. Chopin was enchanted with the place, and refused to go back to Paris. Madame Dupine insisted, and explained to him that she took him to Majorca to spend the Winter, but she had no intention or thought of caring for him longer than the few months that might be required to restore him to health. But he cried and clung to her with such half-childish fright that she had not the heart to send him away.

The summer months passed and the leaves began to turn scarlet and gold, and he only consented to return to Paris on her agreeing to go with him. So they returned together, and had rooms not so very far apart.

He went back sturdily to his music-teaching, with an occasional musicale, yet gave but one public concert in the space of ten years.

The exquisite quality of Chopin’s playing appealed only to the sacred few, but his piano scores were slowly finding sale, through the advertisement they received by being played by Liszt, Tausig and others. Yet the critics almost uniformly condemned his work as bizarre and erratic.

Each Summer he spent at lovely Nohant, and there found the rest and quiet which got nerves back to the norm and allowed him to go on with his work. So passed the years away. Of this we are very sure—no taint exists on the record of Chopin excepting possibly his relationship with George Sand. That he endeavored to win her full heart’s love, for the purpose of honorable marriage, Mr. Hadow is fully convinced. But when his suit failed, after an eight years’ courtship, and the lover was discarded, he ceased to work. His heart was broken; he lingered on for two years, and then death claimed him at the early age of forty years.

here is a tendency to judge a work of art by its size. Thus the sculptor who does a “heroic figure” is the man who looms large to the average visitor at the art-gallery.

Chopin wrote no lengthy symphonies, oratorios or operas. His music is poetry set to exquisite sounds. Poetry is an ecstasy of the spirit, and ecstasies in their very nature are not sustained moods.

The poetic mood is transient. A composition by Chopin is a soul-ecstasy, like unto the singing of a lark.

No other man but Chopin should have been allowed to set the songs of Shelley to music. With such names as Shelley, Keats, Poe and Crane must Chopin’s name be linked.

In Chopin’s music there is much loose texture; there are wide-meshed chords, daring leaps and abrupt arpeggios. These have often been pointed out as faults, but such harmonious discords are now properly valued, and we see that Chopin’s lapses all had meaning and purpose, in that they impart a feeling—making their appeal to souls that have suffered—souls that know.

More of Chopin’s music is sold in America every year than was sold altogether during the lifetime of the composer. His name and fame grow with each year. Everywhere—wherever a piano is played—on concert platform, in studio or private parlor, there you will find the work of Frederic Chopin. That such a widespread distribution must have a potent and powerful effect upon the race goes without argument, although the furthest limit of that influence no man can mark. It is registered with Infinity alone. And thus does that modest, mild and gentle revolutionist Frederic Chopin live again in minds made better.