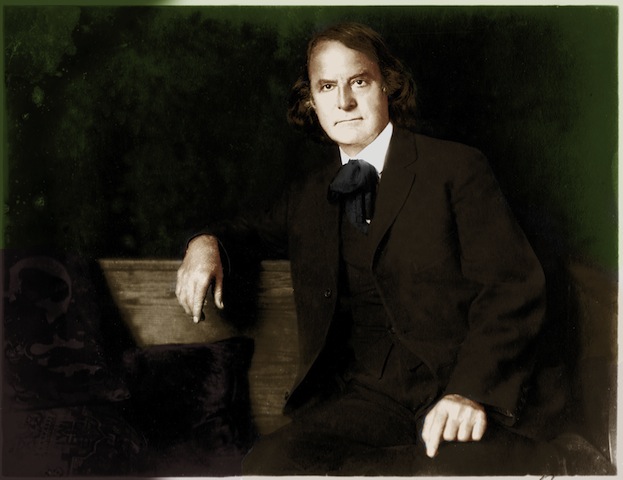

Elbert Green Hubbard (June 19, 1856-May 7, 1915) was an American writer, publisher, artist, and philosopher. Raised in Hudson, Illinois, he met early success as a traveling salesman with the Larkin soap company. Today Hubbard is mostly known as the founder of the Roycroft artisan community in East Aurora, New York, an influential proponent of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

His masterwork was a 14-volume collection of biographical sketches under the title Little Journeys to, with the 14 volumes being: (v. 1) To the homes of good men and great; (v. 2) To the homes of famous women; (v. 3) To the homes of American statesmen; (v. 4) To the homes of eminent painters; (v. 5) To the homes of English authors; (v. 6) To the homes of eminent artists; (v. 7) To the homes of eminent orators; (v. 8) To the homes of great philosophers; (v. 9) To the homes of great reformers; (v. 10) To the homes of great teachers; (v. 11) To the homes of great business men; (v. 12) To the homes of great scientists; (v. 13) To the homes of great lovers; (v. 14) To the homes of great musicians.

In 1912, the famed passenger liner the Titanic was sunk after hitting an iceberg. Hubbard subsequently wrote of the disaster, singling out the story of Ida Straus, who as a woman was supposed to be placed on a lifeboat in precedence to the men, but she refused to board the boat: “Not I—I will not leave my husband. All these years we’ve traveled together, and shall we part now? No, our fate is one.” Hubbard then added his own stirring commentary:

“Mr. and Mrs. Straus, I envy you that legacy of love and loyalty left to your children and grandchildren. The calm courage that was yours all your long and useful career was your possession in death. You knew how to do three great things—you knew how to live, how to love and how to die. One thing is sure, there are just two respectable ways to die. One is of old age, and the other is by accident. All disease is indecent. Suicide is atrocious. But to pass out as did Mr. and Mrs. Isador Straus is glorious. Few have such a privilege. Happy lovers, both. In life they were never separated and in death they are not divided.”

Ironically, a little more than three years after the sinking of the Titanic, Hubbard and his wife, Alice Moore Hubbard, had boarded the RMS Lusitania in New York City. On May 7, 1915, while at sea 11 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, it was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-boat U-20.

In a letter to Elbert Hubbard II dated 12 March 1916, Ernest C. Cowper, a survivor of this event, wrote:

I cannot say specifically where your father and Mrs. Hubbard were when the torpedoes hit, but I can tell you just what happened after that. They emerged from their room, which was on the port side of the vessel, and came on to the boat-deck

Neither appeared perturbed in the least. Your father and Mrs. Hubbard linked arms—the fashion in which they always walked the deck—and stood apparently wondering what to do. I passed him with a baby which I was taking to a lifeboat when he said, “Well, Jack, they have got us. They are a damn sight worse than I ever thought they were.”

They did not move very far away from where they originally stood. As I moved to the other side of the ship, in preparation for a jump when the right moment came, I called to him, “What are you going to do?” and he just shook his head, while Mrs. Hubbard smiled and said, “There does not seem to be anything to do.”

The expression seemed to produce action on the part of your father, for then he did one of the most dramatic things I ever saw done. He simply turned with Mrs. Hubbard and entered a room on the top deck, the door of which was open, and closed it behind him.

It was apparent that his idea was that they should die together, and not risk being parted on going into the water.

Elbert Hubbard’s life was in many ways as colorful, if not as influential, as those whom he profiled in his Great books series. The following chapter about Mozart is a perfect example: it begins not with the young musical genius dazzling the elders, but with Hubbard’s account of how he left his manuscript of this chapter unattended on a train and returned to find the porter had tossed it out a window thinking it was trash. Another passenger told him she had seen its pages blowing across the prairie. He explains it all below, before he starts in on Mozart. It’s highly entertaining.

The following chapter is from Hubbard’s 1901 volume, Little Journeys To the Homes of the Great: Great Musicians.

Mozart composed nine hundred twenty-two pieces of which we know. He is considered the greatest composer the world has ever seen, judged by the versatility and power of his genius. In every kind of composition he was equally excellent. Beside being a great composer he was a great performer, being the most accomplished pianist of his day. He was also an excellent player on the violin. -—Dudley Buck

Little Journeys To the Homes of the Great

Elbert Hubbard

Printed and made into a Book by

The Roycrofters, who are in East

Aurora, Erie County, New York

Wm. H. Wise & Co.

New York

WOLFGANG MOZART

pology: The Mozart “Little Journey” was written, and as over a month had been taken to do the task, the result was something of which I was justly proud. It was quite unlike anything ever before written. The printers were ready to take the work in hand, but I begged them to allow me two more days for careful revision; and as I was just starting away to give a lecture at Janesville, Wisconsin, I took the manuscript with me, intending to do the final work of revision on the train.

All went well on the journey, the lecture had been given with no special tokens of disapproval on part of the audience, and I was on board the early morning train that leaves for Chicago. And as my mind is usually fairly clear in the early hours, I began work retouching the good manuscript. We were nearing Beloit when I bethought me to go into the Buffet-Car for a moment.

Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (complete) (1788)

When I returned the manuscript was not to be seen. I looked in various seats, and under the seats, asked my neighbors, inquired of the brakeman, and then hunted up the porter and asked him if he had seen my manuscript. He did not at first understand what I meant by the term “manuscript,” but finally inquired if I referred to a pile of dirty, dog-eared sheets of paper, all marked up and down and over and crisscross, ev’ry-which-way.

I assured him that he understood the case.

He then informed me that he had “chucked the stuff,” that is to say, he had tossed it out of the window, as he was cleaning up his car, just as he always did before reaching Chicago.

I made a frantic reach for the bell-cord, but was restrained. A sympathetic passenger came forward and explained that five miles back he had seen the sheets of my precious manuscript sailing across the prairie. We were going at the rate of a mile a minute and the wind was blowing fiercely, so there was really no need of backing up the train to regain the lost goods.

“I hope dem scribbled papers was no ‘count, boss!” said the porter humbly, as I stood sort of dazed, gazing into vacancy.

I shook myself into partial sanity. “Oh, they were of no value—I was looking for them so as to throw them out of the window myself,” I answered.

“Brush?” said he.

“Yes,” said I.

I placed the expected quarter in his dusky palm, still pondering on what I should do.

To reproduce the matter was impossible, for I have no verbal memory—something must be written, though. I decided to leave Chicago in an hour by the Lake Shore Railroad, and have the copy ready for the Roycroft boys when I reached home.

Glenn Gould, Mozart Fantasia in C minor K475 (1/2)

Glenn Gould, Mozart Fantasia in C minor K475 (2/2)

This I did, and as I had no reference-books, maps or memoranda to guide me, the matter seems to lack synthesis. I say seems to lack—but it really doesn’t, for the facts will all be found to be as stated. Still the form may be said to be slightly colored by the environment, so some explanation is in order—hence this apology to the Gentle Reader. And further, if the Reader should find in these pages that, at rare intervals, I use the personal pronoun, he must bear in mind that I live in the country, and that it is the privilege and right, established by long precedent and custom of country folk, to talk about themselves and their own affairs if they are so minded.

hicago: Talent is usually purchased at a high price, and if the gods give you a generous supply of this, they probably will be niggardly when it comes to that. But one thing the artist is usually long on, and that is whim. Let us all pray to be delivered from whim—it is the poisoner of our joys, the corrupter of our peace, and Dead-Sea fruit for all those about us.

Heaven deliver us from whim!

I am told by a famous impresario, who gained some valuable experience by marrying a prima donna, and therefore should know, that whim is purely a feminine attribute. This, though, is surely a mistake, for there have lived men, as well as women, who had such an exaggerated sense of their own worth, that they lost sight, entirely, of the rights and feelings of everybody else. All through life they kept the stage waiting without punctilio. These men thought dogs were made to kick, servants to rail at, the public to be first crawled to and then damned, and all rivals to be pooh-poohed, cursed or feared, as the mood might prompt. Further than this they considered all landlords robbers, every railroad-manager a rogue, and businessmen they bunched as greedy, grasping Shylocks. They always used the word “commercial” as an epithet.

Devotees of the histrionic art can lay just claim to having more than their share of whim, but the musical profession has no reason to be abashed, for it is a good second. However, the actor’s and the musician’s art are often not far separated. In speaking to James McNeil Whistler of a certain versatile musician, a lady once said, “I believe he also acts!”

“Madame, he does nothing else,” replied Mr. Whistler.

Mozart, Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra in B Major KV 191. RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Alpasian Ertungealp, soloist Aleksandar Ranisavljev. Ljubljana, Slovenia, February 26, 2012.

Art is not a thing separate and apart—art is only the beautiful way of doing things. And is it not most absurd to think, because a man has the faculty of doing a thing well, that on this account he should assume airs and declare himself exempt along the line of morals and manners? The expression “artistic temperament” is often an apologetic term, like “literary sensitiveness,” which means that the man has stuck to one task so long that he is unable to meet his brother men on a respectful equality.

The artist is the voluptuary of labor, and his fantastic tricks often seem to be only Nature’s way of equalizing matters, and showing the world that he is very common clay, after all. To be modest and gentle and kind, as we all can be, is just as much to God as to be learned and talented, and yet be a cad.

Still, instances of great talent and becoming modesty are sometimes found; and in no great musician was the balance of virtues held more gracefully than with Mozart. He had humor.

Ah! that is it—he knew values—had a sense of proportion, and realized that there is a time to laugh. And a good time to laugh is when you see a mighty bundle of pretense and affectation coming down the street. Dignity is the mask behind which we hide our ignorance; and our forced dignity is what makes the imps of comedy, who sit aloft in the sky, hold their sides in merriment when they behold us demanding obeisance because we have fallen heir to tuppence worth of talent.

aporte: Mozart had a sense of humor. He knew a big thing from a little one. When yet a child the tendency to comedy was strong upon him. When nine years of age he once played at a private musicale where the Empress, Maria Theresa, was present. The lad even then was a consummate violinist. He had just played a piece that contained such a tender, mournful, minor strain that several of the ladies were in tears. The boy seeing this, relentingly dashed off into a “barnyard symphony,” where donkeys brayed, hens cackled, pigs squealed and cows mooed, all ending with a terrific cat-fight on a wood-shed roof. This done, the boy threw his violin down, ran across the room, climbed into the lap of the Empress and throwing his arms around the neck of the good lady, kissed her a resounding smack first on one cheek, then on the other. It was all very much like that performance of Liszt, who one day, when he was playing the piano, suddenly shouted, “Pitch everything out of the windows!” and then proceeded to do it—on the keyboard, of course.

On the same visit to the palace, when Mozart saluted Maria Theresa in his playful way, he had the misfortune to slip and fall on the waxed floor.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmzyD5zo7i4

Leonard Bernstein conducts the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks in Mozart’s Requiem K. 626. Marie McLaughlin, soprano; Maria Ewing, mezzo-soprano; Jerry Hadley, tenor; Cornelius Hauptmann, bass; Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks.

Marie Antoinette, daughter of Maria Theresa, just budding into womanhood, ran and picked him up and rubbed his knee where it was hurt. “You are a dear, good lady,” said the boy in gratitude, “and when I grow up I am going to marry you.” Liszt never made any such promise as that. Liszt never offered to marry anybody. But it is too bad that Marie Antoinette did not hold the lad to his promise. It would have probably proved a valuable factor for her in the line of longevity; and her husband’s circumstances would have saved her from making that silly inquiry as to why poor people don’t eat cake when they run short of bread. These moods of merriment continued with Mozart, as they did with Liszt, all his life—not always manifesting themselves, though, in the way just described.

As a companion I would choose Mozart—generous, unaffected, kind—rather than any other musician who ever played, danced, sang or composed—excepting, well, say Brahms.

outh Bend: We take an interest in the lives of others because we always, when we think of another, imagine our relationship to him. “Had I met Shakespeare on the stairs I would have fainted dead away,” said Thackeray.

Another reason why we are interested in biography is because, to a degree, it is a repetition of our own life.

There are certain things that happen to every one, and others we think might have happened to us, and may yet. So as we read, we unconsciously slip into the life of the other man and confuse our identity with his. To put yourself in his place is the only way to understand and appreciate him. It is imagination that gives us this faculty of transmigration of souls; and to have imagination is to be universal; not to have it is to be provincial. Let me see—wouldn’t you rather be a citizen of the Universe than a citizen of Peoria, Illinois, which modest town the actors always speak of as being one of the provinces?

As I read biography I always keep thinking what I would have done in certain described circumstances, and so not only am I living the other man’s life, but I am comparing my nature with his. Everything is comparative; that is the only way we realize anything—by comparing it with something else. As you read of the great man he seems very near to you. You reach out across the years and touch hands with him, and with him you hope, suffer, strive and enjoy: your existence is all blurred and fused with his.

And through this oneness you come to know and comprehend a character that has once existed, very much better than the people did who lived in his day and were blind to his true worth by being ensnared in cliques that were in competition with him.

lkhart: I intimated a few pages back that I would have liked to have Mozart for a friend and companion. Mozart needed me no less than I need him. “Genius needs a keeper,” once said I. Zangwill, probably with himself in mind. We all need friends—and to be your brother’s keeper is very excellent if you do not cease being his friend. And poor Mozart did so need a friend who could stand between him and the rapacious wolf that scratched and sniffed at his door as long as he lived. I do not know why the wolf sniffed, for Mozart really never had anything worth carrying away. He was so generous that his purse was always open, and so full of unmixed pity that the beggars passed his name along and made cabalistic marks on his gateposts. Every seedy, needy, thirsty and ill-appreciated musician in Germany regarded him as lawful prey. They used to say to Mozart, “I can not beg and to dig I am ashamed—so grant me a small loan, I pray thee.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zPkWVqdJXI

The Haydn Ensemble of Berlin performs Mozart’s Concerto for Flute and Orchestra G-dur K 313 (285C)

Yes, Mozart needed me to plan his tours and market his wares. I’m no genius, and although they say I was an infant terrible, I never was an infant prodigy. At the tender age of six, Mozart was giving concerts and astonishing Europe with his subtle skill. At a like age I could catch a horse with a nubbin, climb his back, and without a saddle or bridle drive him wherever I listed by the judicious use of a tattered hat. Of course I took pains to mount only a horse that had arrived at years of discretion, matronly brood-mares or run-down plow-horses; but this is only proof of my practical turn of mind. Mozart never learned how to control either horse or man by means of a tattered hat or diplomacy: music was his hobby, and it was long years after his death before the world discovered that his hobby was no hobby at all, but a genuine automobile that carried him miles and miles, clear beyond all his competitors: so far ahead that he was really out of shouting distance.

Indeed, Mozart took such an early start in life and drove his machinery so steadily, not to say so furiously, that at thirty-five all the bearings grew hot for lack of rebabbitting, and the vehicle went the way of the one-horse shay—all at once and nothing first, just as bubbles do when they burst.

At the age which Mozart died I had seen all I wanted to of business life, in fact I had made a fortune, being the only man in America who had all the money he wanted, and so just turned about and went to college. This I firmly hold is a better way than to be sent to college and then go into trade later and forget all you ever learned at school. I had rather go to college than be sent. Every man should get rich, that he might know the worthlessness of riches; and every man should have a college education, just to realize how little the thing is worth.

Yes, Mozart needed a good friend whose abilities could have rounded out and made good his deficiencies. Most certainly I could not do the things that he did, but I should have been his helper, and might, too, had not a century, one wide ocean, and a foreign language separated us.

aterloo: Friendship is better than love for a steady diet. Suspicion, jealousy, prejudice and strife follow in the wake of love; and disgrace, murder and suicide lurk just around the corner from where love coos. Love is a matter of propinquity; it makes demands, asks for proofs, requires a token. But friendship seeks no ownership—-it only hopes to serve, and it grows by giving. Do not say, please, that this applies also to love. Love bestows only that it may receive, and a one-sided passion turns to hate in a night, and then demands vengeance as its right and portion.

Friendship asks no rash promises, demands no foolish vows, is strongest in absence, and most loyal when needed. It lends ballast to life, and gives steadily to every venture. Through our friends we are made brothers to all who live.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c91sftnGkZY

Mozart Piano Concerto No. 25 C Major K 503. Riccardo Muti conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, Mitsuko Uchida, piano.

I think I would rather have had Mozart for a friend than to love and be loved by the greatest prima donna who ever warbled in high C. Friendship is better than love. Friendship means calm, sweet sleep, clear brain and a strong hold on sanity. Love I am told is only friendship, plus something else. But that something else is a great disturber of the peace, not to say digestion. It sometimes racks the brain until the world reels. Love is such a tax on the emotions that this way madness lies. Friendship never yet led to suicide.

oledo: Yes, just at the age when Mozart wrote and played his “Requiem,” getting ready to die, I was going to school and incidentally falling in love. I was thirty-four and shaved clean because there were gray hairs coming in my beard. Love has its advantages, of course, and the benefits of passionate love consist in scarifying one’s sensibilities until they are raw, thus making one able to sympathize with those who suffer. Love sounds the feelings with a leaden plummet that sinks to the very depths of one’s soul. This once done the emotions can return with ease, and so this is why no singer can sing, or painter paint, or sculptor model, or writer write, until love or calamity, often the same thing, has sounded the depths of his soul. Love makes us wise because it makes room inside the soul for thoughts and feelings to germinate; but passionate love as a lasting mood would be hell. Henry Finck says that is why Nature has fixed a two-year limit on romantic or passionate love. “War is hell,” said General Sherman. “All is fair in Love and War,” says the old proverb. Love and War are one, say I. Love is mad, raging unrest and a vain, hot, reaching out for nobody knows what. Of course the kind which I am talking about is the Grand Passion, not the sort of sentiment that one entertains towards his grandmother.

“But it is good to fall in love, just as it is well to have the measles,” to quote Schopenhauer. Still, there is this difference: one only has the measles once, but the man who has loved is never immune, and no amount of pledges or resolves can ere avail.

Just here seems a good place to express a regret that the English language is such a crude affair that we use the same word to express a man’s regard for roast-beef, his dog, child, wife and Deity. There are those who speedily cry, “Hold!” when one attempts to improve on the language, but I now give notice that on the first rainy day I am going to create some distinctions and differentiate for posterity along the line just mentioned.

lyria: As intimated in a former chapter, I was a successful farmer before I went to college. I was also a manufacturer, and made a success in this business, too. I made a fortune of a hundred thousand dollars before I was thirty, and should have it yet had I sat down and watched it. If you go into a railroad-car and sit down by the side of your valise (or manuscript), in an hour your valuables will probably be there all right.

But if you leave the valise (or the manuscript) in a seat and go into another car, when you come back the goods may be there and they may not. That is the only way to keep money—fasten your eye right on it. If you leave it in the hands of others, and go away to delve in books, the probabilities are that, when you get back, certain obese attorneys have divided your substance among them.

However, there is good in every exigency of life, and to know that your fortune is gone is a great relief. When the trial is ended and the prisoner has received his sentence, he feels a great relief, for it is only the unknown that fills our souls with apprehension.

leveland: In all the realm of artistic history no record of such extremes can be found in one life as those seen in the life of Mozart. The nearest approach to it is found in the career of Rembrandt, who won fame and fortune at thirty, and then holding the pennant high for ten years, his powers began to decline. It took twenty-six years of steady down grade to ditch his destinies in a pauper’s grave.

But Rembrandt, during his lifetime, was scarcely known out of Holland, whereas Mozart not only won the nod of nobility, and the favor of the highest in his own land, but he went into the enemy’s country and captured Italy. Mozart’s art never languished: he held a firm grip on sublime verities right to the day of his death. The high-water mark in Mozart’s career was reached in those two years in Italy, when in his thirteenth and fourteenth years. The arts all go hand in hand, for the reason that strong men inspire strong men, and each does what he can do best. In painting, sculpture and music (not to mention Antonio Stradivari of Cremona) Italy has led the world. A hundred years ago no musician could hope for the world’s acclaim until Italy had placed its stamp of approval upon him.

Savants in Milan, Florence, Padua, Rome, Verona, Venice and Naples, tested the powers of young Mozart to their fullest; and although he had to overcome doubt and the prejudice arising from being “a barbaric German,” yet the highest honors were at the last ungrudgingly paid him. He was enrolled as an honorary member of numerous musical societies, old musicians gave their blessings, proud ladies craved the privilege of kissing his fair forehead, and the Pope conferred upon the gifted boy the Order of the Golden Spur, which gave him the right to have his mail come directed to “The Signor Cavaliere Mozarti.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N-mA9OMP3DE

Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K 216. Gustavo Dudamel conducts the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hilary Hahn, violin

At Naples the result of his marvelous playing was ascribed to enchantment, and this was thought to be centered in a diamond ring that had been presented to the lad by a fair lady in a mood of ecstasy. To convince the Neapolitans of their error Mozart was obliged to accept their challenge and remove the ring. He wrote home to his mother that he had no time to practise, as in every city where he went artists insisted on his sitting for his portrait.

The acme of attention and applause was reached at Milan, where he was commissioned to write an opera for the Christmas festivities. The production of this opera at La Scala was the most glorious item in the life of Mozart. A boy of fourteen conducting an opera of his own composition before enraptured multitudes is an event that stands to the credit of Mozart, and Mozart alone. “Evviva the Little Master—Evviva the Little Master!” cried the audience. “It is music for the stars,” and against all precedent aria after aria had to be repeated. The boy, always rather small for his age, stood on a chair to wield his baton, and the flowers that were rained upon him nearly covered the lad from view.

htabula: The place of a man’s birth does not honor him until after he is dead, and every man of genius has been distrusted by his intimate kinsmen. If he is granted recognition by the outside world, those who have known him from childhood wink slyly and repeat Phineas T. Barnum’s aphorism, a free paraphrase of which the Germans have used since the days of the Vandals.

Leopold Mozart returned home with his wonderful boy not much richer than when he went away. He had left the management of finances to others, and was quite content to travel in a special carriage, stop at the best hotels, and have any “label” he might order, just for the asking.

Reports had reached Germany of the wonderful success of the youthful Mozart in Italy, but Vienna smiled and Salzburg sneezed.

orth East: It is not so very long ago that all the beautiful things of earth were supposed to belong to the Superior Class. That is to say, all the toilers, all the workers in metals, all the bookmakers, authors, poets, painters, sculptors and musicians, did their work to please this noble or that. All bands of singers were singers to His Lordship, and if a man wrote a book he dedicated it to His Royal Highness. At first these thinkers and doers were veritable slaves, and no court was complete that did not have its wise man who wore the cap and bells, and made puns, epigrams and quoted wise saws and modern instances for his board and keep. This man usually served as a clerk or overseer, during his odd hours, and only appeared to give a taste of his quality when he was sent for.

It was the same with the musicians and singers—they were cooks, waiters and valets, and when there were guests these performers were notified to be in readiness to “do something” if called upon. It was the same with painters—every court had its own. Rubens, as we know, was looked upon by the Duke of Mantua as his private property, and the artist had to run away, when the time was ripe, to save his soul alive. Van Dyck was court painter to Charles the First, and married when he was told to do so.

Mozart Violin Sonata No 18 in G Major, K 301, Hilary Hahn, violin; Natalie Zhu, piano

There is no such office as “Poet Laureate of England”—the Laureate is poet to the King, and used to dine with the Master of the Hounds. Later he was allowed to choose his domicile and live in his own house, like Saint Paul, the prisoner at Rome. His yearly stipend is yet that tierce of Canary.

ilver Creek: Leopold Mozart, and the son who caused his name to endure, were in the employ of the Archbishop of Salzburg. The Archbishop was a veritable prince, with short breath and a double chin, and no shade of doubt ever came to him concerning the divinity of his succession. He ruled by divine right, and everybody and everything were made to minister to the well-being of his person and estate. The Mozarts were too poor to escape from the employ of the Archbishop, and he took pains to warn all interested persons not to harbor, encourage or entice his servants away on penalty of dire displeasure. Mozart ate with the servants, and we have his letters written to his sister showing how his seat was next below that of the coachman. When he was to play before invited guests he was made to wait in the entry until the footman called him, and there he often stood for hours, first on one foot, then on t’ other.

It is easy to ask why a man of such sublime talent should endure such treatment, but the simple fact is Mozart was gentle, yielding, kind—immersed in his music—with no power to set his will against the tide of tendency that ‘compassed him round. The Archbishop forbade his playing at concerts or entertainments, and blocked the way to all advancement. The Archbishop didn’t have a diplomat like Rubens to cope with, or a fighter like Wagner, or a plotter like Liszt, or a stiletto-bearing man like Paganini, and so Mozart wrote his music on a table in one corner of a beer-garden, and waltzed with his wife, Constance, to keep warm when there was no fire and the weather was cold, and all the time danced attendance on the Archbishop of Salzburg. All of his feeble, spasmodic efforts at freedom came to naught, because there was no persistency behind them.

Gladly would he have sold his services for three hundred gulden a year, but even this sum, equal to one hundred fifty dollars a year, was denied him. He was always composing, always making plans, always seeing the silver tint in the clouds, but all of his music was taken by this one or that in whom he foolishly trusted, and only debt and humiliation followed him.

When at long intervals a sum would come his way from a generous admirer touched with pity, all the beggars in the neighborhood seemed to know it at once. Then it was that music filled the air at the beer-garden, carking care and unkind fate were for the time forgot, and all went merry as a wedding-bell.

Finally the position of Court Musician to the Emperor of Austria fell vacant, and certain good friends of Mozart secured him the place. But the Emperor was not like Frederick the Great, for he could not distinguish one tune from another, and did not consider it any special virtue so to do. The result was that his musicians were looked after by his valet, and Mozart found that his position was really no better than it had been with the Archbishop of Salzburg.

And still his mind proved infirm of purpose, and he had not the courage to demand his right, for fear he might lose even the little that he had.

uffalo: Mozart was in his twentieth year when he met Aloysia Weber. She was a gifted singer, surely, and was needlessly healthy. She was of that peculiar, heartless type that finds digression in leading men a merry chase and then flaunting and flouting them. Young Mozart, the impressionable, Mozart the delicate and sensitive, Mozart the Æolian harp, played upon by every passing breeze, loved this bouncing bundle of pink-and-white tyranny.

She encouraged the passion, and it gradually grew until it absorbed the boy and he grew oblivious to all else. He lived in her smile, bathed in the sunshine of her presence, fed on her words, and as for her singing in opera it was not so much what her voice was now but what he was sure it would be.

Mozart, Sonata for Keyboard Four-hands in D major, K 381. Anastasia Gromoglasova (primo) and Liubov Gromoglasova (secondo) performing at their duo recital at the Small hall of the Moscow Conservatoire.

His glowing imagination made good her every deficiency. He thought he loved the girl. It was not the girl at all he loved: he only loved the ideal that existed in his own heart. His father opposed the mating and hastily transferred the youth from Vienna to Paris; but who ever heard of opposition and argument and forced separation curing love? So matters ran on and letters and messages passed, and finally Mozart made his way back to Vienna and with breathless haste sought out the object of his whole heart’s love.

She had recently met a man she liked better, and as she could not hold them both, treated Mozart as a stranger, and froze him to the marrow.

He was crushed, undone, and a fit of sickness followed. In his illness, Constance, a younger sister of Aloysia, came to him in pity and nursed him as a child. Very naturally, all the love he had felt for Aloysia was easily and readily transferred to Constance. The tendrils of the heart ruthlessly uprooted cling to the first object that presents itself.

And so Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constance Weber were married. And they were happy ever afterward. It would have been much better if they had quarreled, but Mozart’s gentle, yielding character readily adapted itself to the weaker nature of his wife. In his music she took a sort of blind and deaf delight and guessed its greatness because she loved the man. But when two weak wills combine, the net result is increased weakness—never strength.

Constance was as beautiful a specimen of the slipshod housekeeper as ever piled away breakfast dishes unwashed, or swept dirt under a settee. If they had money she bought things they did not need, and if there was no money she borrowed provisions and forgot to return the loan. Irregularity of living, deprivation and hope deferred, made the woman ill and she became a chronic sufferer. But she was ever tended with loving, patient care by the overburdened and underfed husband.

A biographer tells how Mozart would often arise early in the morning to set down some melody in music that he had dreamed out during the night. On such occasions he would leave a little love-letter for his wife on the stand at the head of the bed, where she would find it on first awakening. One such note, freely translated, runs as follows: “Good-morning, Dear Little Wife. I hope you rested well and had sweet dreams. You were sleeping so peacefully that I dare not kiss your cheek for fear of disturbing you. It is a beautiful morning and a bird outside is singing a song that is in my heart. I am going out to catch the strain and write it down as my own and yours. I shall be back in an hour.”

ast Aurora: Aloysia married the man of her choice—an actor by the name of Lange. They quarreled right shortly, and soon he used to beat her. This was endured for a year or more, then she left him. For a while she lived with Wolfgang and Constance, and Mozart, true to his nature, gave her from his own scanty store and deprived himself for her benefit. He stood godfather to one of her children and was a true friend to her to the last.

After Aloysia lived to be an old woman, and long after Mozart had passed out, and the world had begun to utter his praises, she said: “I never for a moment thought he was a genius—I always considered him just a nice little man.”

Mozart’s soul was filled with melody, and all of his music is faultless and complete. He possessed the artistic conscience to a degree that is unique. Careless and heedless in all else, if his mood was not right and the product was halting, he straightway destroyed the score. He was always at work, always hearing sweet sounds, always weighing and balancing them in the delicate scales of his judgment.

Midsummer Mozart Festival Orchestra Ensemble: George Cleve, music director with Robin Hansen/Christina Mok/Lylian Guion/Adrienne Sengpiehl/Candace Guirao, violins/Patrick Kroboth/ David Bowes, violas/Dawn Foster-Dodson/Wanda Warkentin, cellos/Tim Spears, bass/Maria Tamburrino, flute perform Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Serenade No.13 for strings in G Major, K. 525 ‘Eine kleine Nachtmusik,’ June 7, 2011 at San Francisco’s Noontime Concerts, Old St. Mary’s Cathedral

So absorbed was he in his art that he fell an easy victim to the designing, and never stopped his work long enough to strike off the shackles that bound him to a vain, selfish and unappreciative court.

Worn by constant work, worried by his wife’s continued illness, dogged by creditors, and unable to get justice from those who owed it to him, his nerves at the early age of thirty-five gave way.

His vitality rapidly declined and at last went out as a candle does when blown upon by a sudden gust from an open door.

It was a blustering winter day in December, Seventeen Hundred Ninety-one, when his burial occurred. A little company of friends assembled, but no funeral-dirge was played for him, save the blast blown through the naked branches of the trees, as they hurried the plain pine coffin to its final resting-place. At the gate of the cemetery the few friends turned back and left the lifeless clay to the old gravedigger, who never guessed the honor thus done him.

It was a pauper’s grave that closed over the body of Mozart—coffin piled on coffin, and no one marked the spot. All we know is, that somewhere in Saint Mark’s Cemetery, Vienna, was buried in a trench the most accomplished composer and performer the world has ever known. It was a hundred years afterward before the city made tardy amends by erecting a fitting monument to his memory.

His best monument is his work. The melody that once filled his soul is yours and mine; for by his art he made us heirs to all that wealth of love that was never requited, and the dreams, that for him never came true, are our precious and priceless legacy.