Blues fans in Houston, Texas, knew something was wrong with one of their favorite artists when the ace guitarist and songwriter known as Texas Johnny Brown-although he hailed from Mississippi-cancelled one of his regular gigs at the Big Easy Social and Pleasure Club earlier this year.

On July 1 word came that Brown had succumbed to lung cancer. Diagnosed with the illness this past May, he kept news of his condition to himself and continued gigging. “He didn’t want to announce anything, wanted simply to keep gigging till the end,” reported his friend, blues historian Roger Wood in a statement to reporter Andrew Densby in the Houston Chronicle. Brown’s son Shawn cared for his father, who declined chemotherapy and was being treated in a hospice, and was at his bedside when he crossed over on the evening of July 1.

Although Brown released two acclaimed albums–1998’s Nothin’ But the Truth and 2001’s Blues Defender (both on the Choctaw Creek label based in his native Mississippi)–he wrote his name large in blues history with his original song “Two Steps from the Blues,” which his friend Bobby “Blue” Bland recorded as the title track of his now-legendary 1961 album, which became a monument in Bland’s storied career. Bland hired Brown as his guitarist and bandleader, and the two toured extensively in the ’50s and ’60s; they died within a week of each other, with Bland passing on June 23. (See the Deep Roots tribute to Bobby “Blue” Bland here.)

Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland’s monumental recording of Texas Johnny Brown’s song, ‘Two Steps from the Blues’

Texas Johnny Brown, an instrumental version of Carolyn Franklin’s ‘Ain’t No Way’ from his 1998 album, Nothin’ But the Truth

Brown’s family made the trip from Texas to his native Ackerman, Mississippi on the weekend of July 12-14 to honor his final wish to have his ashes spread at Mt. Salem Baptist Church in Ackerman in Choctaw County.

Brown had been a rock of Houston’s blues community since he arrived in town in 1946 to begin a four-year tenure playing with Amos Milburn and the Chickenshackers; it was, in fact, Milburn’s manager who suggested to Brown that he adopt a stage name that reflected his popularity in and around Houston, to wit, Texas Johnny Brown, and Brown agreed, saying simply, “That’s all right with me.”

As “Texas” Johnny Brown and His Blues Rockers (featuring Milburn on piano), Brown recorded the 45 “There Goes the Blues”/”The Blues Rock” for Atlantic in a 1949 session in which he and his band backed Ruth Brown on her first recordings for the label that came to be known in its early days as “the house that Ruth built.”

From Texas Johnny Brown’s first Atlantic session, 1949, ‘Blues Rock’

While working primarily as a session player at Duke/Peacock in the ‘60s, Texas Johnny Brown, billed as Johnny Brown and the Joy Boys, cut a few hot tracks, including the cinematic ‘Suspense’ and the twangy, horn-fired R&B workout, ‘Snakehips

Two other cuts from the 1949 session, “Bongo Boogie” and “Blues Rock,” surfaced on a 1986 Atlantic compilation, and he cut some obscure sides in the ‘60s at Duke/Peacock, where he was employed primarily backing many of the label’s top-drawer blues and R&B artists. After Duke/Peacock, he would not release another recording until the abovementioned albums on Choctaw Creek surfaced in ’98 and ’01. The blue community took notice of those long players in fine fashion. Nothin’ But the Truth, his debut full-length CD, included 11 of his original compositions and featured his elegant guitar playing and his earthy vocals trumpeting the blues with some touches of jazz, soul and zydeco and some spirited brass on the uptempo numbers. The album was nominated for a W.C. Handy Blues Award (1999) for Comeback Album of the Year and received Real Blues Magazine’s Real Blues Award as Best Texas Blues CD (New) and Best Independently Released Blues CD of 1998. Blues Defender included a stirring treatment of Lil Green’s “In the Dark” in addition to ten Brown originals.

In September 2011 Brown was honored by the state of Mississippi with his own plaque, hailing him as being “foremost among Ackerman’s African-American musicians,” on the Mississippi Blues Trail. Brown and his Quality Blues Band attended the unveiling in Ackerman and played a concert celebrating the event. More recently he was a featured artist at the 2012 Chicago Blues Festival.

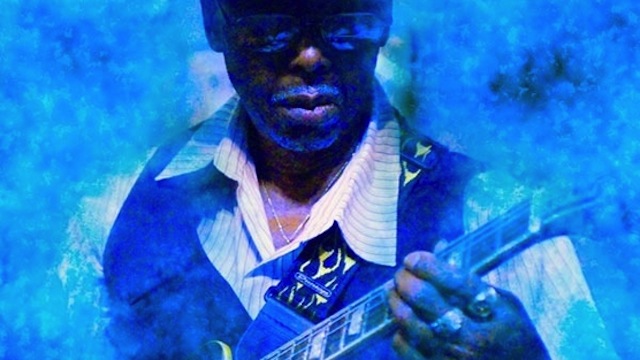

A photo from September 2011 captures Texas Johnny Brown performing in downtown Ackerman, Mississippi, his hometown, after the unveiling of a Mississippi Blues Trail marker in his honor.

Texas Johnny Brown’s reputation was built not on a deep body of work but on pure, unadulterated musicianship of the highest caliber. “The word ‘unique’ gets misused often, but in some respects it accurately describes TJB,” Wood, who wrote about Brown in his book Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues, told the Houston Chronicle. “For one, he’s the only person so clearly linked to Texas to have a historical marker devoted exclusively to his musical career on the Mississippi Blues Trail. I guess he’s the only person playing regularly in Houston over the last decade who recorded under his own name for Atlantic Records in New York City in 1949. And to my ear, his exquisite guitar playing does not sound like anyone else’s.”

Moreover, his death closes the book on one of the most colorful careers in post-war American music. This was a man who, as a child, played on the streets with his musician father, and their dog, the delightfully named Carburetor, who “strummed the guitar on cue” (all seen on screen in the opening sequence of their only film appearance, in 1940’s Virginia) according to Brown’s son Shawn, whose self-penned obituary of his father reads, in part:

John Riley Brown was born February 22, 1928, in Ackerman, MS, to blind bluesman Cranston Exerville “Clarence” Brown and his wife. He had two brothers and three sisters: Cranston Exerville “Pete,” Robert, Daisy Mae, Maureen, and Margie.

Johnny attended Mount Salem Baptist Church and school and later lived in town with his mother until she died when he was nine.

Texas Johnny Brown & the Quality Blues Band live at Houston’s Big Easy, April 24, 2011. Posted at YouTube by David Burkhard.

Johnny went to live with his father, a blind street singer-guitarist and former railroad employee. Young Johnny danced and played tambourine with him, while their dog, Carburetor, strummed the guitar on cue. The Browns lived in New Orleans, LA, and Natchez, MS, in between trips to towns in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

In Natchez, a Hollywood producer, impressed by their act, invited them to Virginia in 1940 to appear in the film Virginia. Twelve-year-old Johnny, his dad, and their dog were featured in the opening sequence.

A few years later, Johnny decided he wanted to join the Merchant Marines. He left home, but only had enough money to buy a train ticket to Alexandria, LA. He knew a few people in Alexandria, including a certain young lady he had a particular fondness for. While working in a music store in Alexandria the owner offered to teach guitar to his 16-year-old employee. The rest is history.

Johnny began his professional musical career in Houston in the mid-1940s with Amos Milburn’s Aladdin Chickenshackers. He played guitar on many of Milburn’s recordings on Aladdin Records, and Milburn and other members of his band backed Johnny during his Atlantic Records recording session in 1949. Johnny also appeared on Ruth Brown’s first Atlantic Records recordings, which were cut during those sessions.

On September 17, 1950, Johnny married the love of his life, Rosie Lee Jones. They had met as teenagers, when she was 13 and he was 16. They were the proud parents of Lynville and Shawn.

Texas Johnny Brown with Bobby Mack at Houston’s Big Easy (Jimmy Pate on drums, Larry Evans on bass), ‘Just Can’t Do It’

Johnny’s musical career was interrupted briefly when he was drafted into the United States Army. After returning from his tour of duty in Korea Johnny resumed his musical career, touring with Bobby “Blue” Bland and Junior Parker in the 1950s and 1960s as guitarist and band leader. He was also a studio musician for Houston’s Duke/Peacock Records. He recorded a number of his own compositions for Duke/Peacock, including “Snakehips” and “Suspense,” and his distinctive guitar style graced the recordings of numerous other Duke/Peacock blues artists, including Bland, Parker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Larry Davis, Lavelle White, Buddy Ace and Joe Hinton. Johnny also wrote the beautiful blues classic, “Two Steps from the Blues,” one of Bland’s biggest hits.

Over the years, Brown took odd jobs but he became a mainstay of Houston’s local blues scene in 1991 after retiring from other work.

After returning to music full-time in 1991, Johnny and his Quality Blues Band performed monthly at the Big Easy Social and Pleasure Club in Houston for years, as well as all across the United States, Canada, and Europe. They also played many prestigious festivals, including the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Washington, D.C.; the Chicago Blues Festival; the Pocono Blues Festival; the Arkansas Blues and Heritage Festival; the Lucerne Blues Festival, Lucerne, Switzerland and numerous others.

Johnny was honored as Blues Artist of the Year at the Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton Blues Festival September 22, 2001 in Houston, TX, and September 22, 2001 was declared Texas Johnny Brown Day in Houston.

He was also been featured on the cover of Juke Blues magazine (England) and Southwest Blues magazine, in Soul Bag magazine (France) and several times in Living Blues Magazine.

A tasty 15 minutes of Texas Johnny Brown performing at Harlingen, Texas’s annual concert series, Blues On the Hill, 2001

Johnny won numerous Houston Press Music Awards for Best Blues, Best Guitarist and Best Male Vocalist.

Despite his many professional accolades, his true legacy is his beautiful smile, warm heart and undying love for his family, fans and the music that brought all of us so much joy.

Johnny was preceded in death by his parents, five siblings, and loving son Lynville.

He leaves to mourn his passing his devoted wife of 63 years, Rosie L. Brown; his dedicated son Shawn (Pflugerville, TX); granddaughters Brooke and Amaya Brown (Pflugerville, TX), and Victoria Colston (Cuero, TX); grandsons Dominique Colston and Kristopher Calhoun (Houston, TX); and a host of in-laws, nieces, nephews, and cousins.