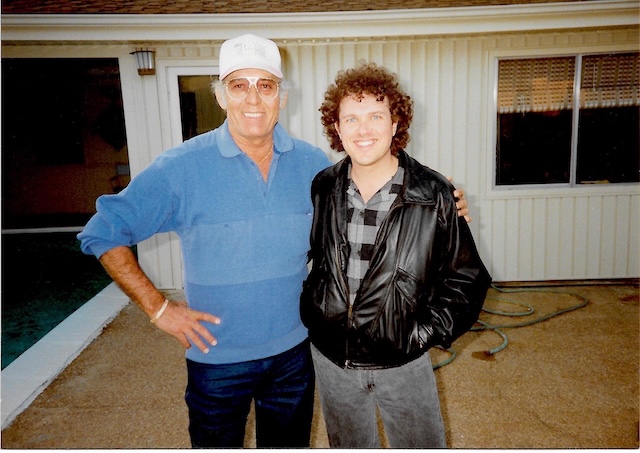

Carl Perkins & Bill Lloyd 1990 Jackson TN

A new Carl Perkins album, recorded in 1990, surfaces in 2025, but its mystery endures

By David McGee

In 1989 Carl Perkins harbored high hopes for an album he had recorded with producers Brent Maher and Don Potter, the creative studio team behind The Judds’ recordings. Yet the favorably reviewed Born to Rock, as the album was titled, collapsed commercially when the label issuing it, Universal Nashville, folded after its president, Jimmy Bowen, took the helm of Capitol Records in Los Angeles. This latest of many professional setbacks Carl had experienced since leaving Sun Records in 1958 led his manager, Ken Stilts (who also managed The Judds), to have a heart-to-heart talk with his charge about the road ahead.

“I told him, ‘I admire and respect where you’re coming from, but I think it’s hurt the commercial aspect of your songwriting’” Stilts recalled when I interviewed him for Carl’s authorized biography, Go, Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly. “Because everything he wrote was very spiritual stuff. I said ‘If you ever get your frame of mind to the point where you were when you were writing things like ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and some of the stuff the Beatles did, you can still have big, big hits. Not just country, but pop.’”

Yet in that same year, in the midst of his despair, Carl had a hit single, one he wrote (with a smidgen of polish added by Paul Kennerley and Brent Maher) and to which he contributed a tough guitar solo, “Let Me Tell You About Love,” a #1 country hit for The Judds. It wasn’t like he had lost his touch. Unfortunately, his next album, released in 1992, would be the disappointing Friends, Family & Legends. Struggling vocally through those sessions, Carl was ultimately diagnosed with throat cancer and fought through seven and a half weeks of radiation treatments that put his career on hold for the better part of three years. In 1996, as he was returning to public life, what would be his final album, Go, Cat, Go!, produced by the formidable Bob Johnston and released on Johnston’s independent Dinosaur label, faded into obscurity as Carl and another heavyweight guest lineup (including George Harrison and Ringo Starr) failed to generate anything memorable, and descended into folly with the inclusion of Jimi Hendrix’s version of “Blue Suede Shoes,” an archival recording absent Carl Perkins’s presence entirely.

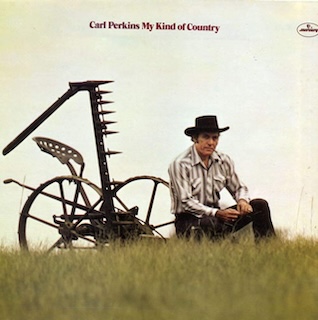

However, in 1990, unbeknownst to hardly anyone beyond the personnel involved in it, Carl had recorded an album’s worth of new songs with producer Bill Lloyd (recruited by Carl’s and The Judds’ booking agent Rick Shipp), the more pop-oriented half of the popular New Traditionalist country duo Foster & Lloyd, which had broken out in 1986 with a #1 country single, “Crazy Over You,” and had opened shows for Carl in four cities while touring in 1989-1990. With the aim of pitching an album project to RCA Nashville’s VP of A&R Mary Martin (Stilts, as The Judds’ manager, had some clout with the label when he came calling), Lloyd guided six days of recording (four in May 1990, three in June) at Carl’s Pool House Studio, so named for its location behind the back yard swimming pool at Carl’s ranch-style house in Jackson, TN. When tape rolled, Carl in turn rolled out some of the finest songs he had penned since his 1973 Mercury Records masterpiece, My Kind of Country—all replete with his gift for colorful wordplay, many of them deeply blues oriented in exploring the vagaries of love and relationships in addition to a couple of lighthearted autobiographical reflections on his life and times, sung in a freewheeling style he rarely cut loose with on record after Sun, and amply showcasing the depth and breadth of his guitar mastery, ranging from blues, rockabilly, country blues, and classic pop, to complex, multi-textured solos to tenderhearted, delicate, Les Paul-style fingerpicking. The lineup was the Perkins touring band: Carl, his son Stan on drums, his son Greg on bass, and, on piano, young Joe Schenk, who had grown up in Carl’s hometown, Tiptonville, Tennessee, and began accompanying Carl on the road in 1987 (after Carl’s passing in 1998, Schenk retired from music, returned to Tiptonville and took up farming full time until his death this past May at age 77). Upon hearing the Pool House Studio sessions, Mary Martin agreed to fund three demos at Nashville’s high-end 16th Avenue Sound, which occurred over four days in mid-September 1990. In recapturing his Sun fire, Carl had indeed recalibrated his “frame of mind,” as Stilts had suggested, delivering strong original material that the collective aggregate played with precision and passion. In a mystery yet unsolved, RCA passed, with no further explanation, not even to Carl Perkins, whose signature song helped create not simply the rock ‘n’ roll business, but an entire culture. Crickets.

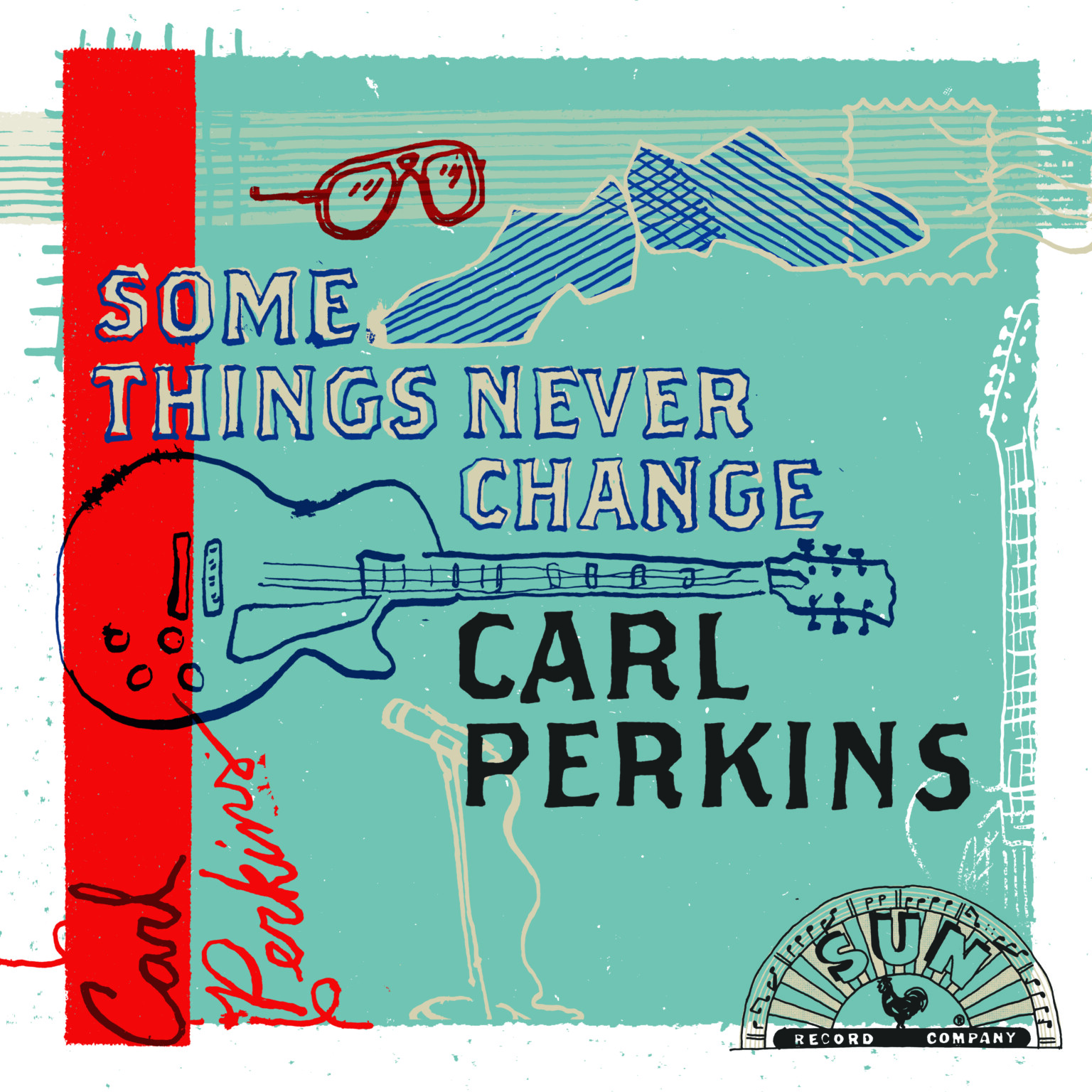

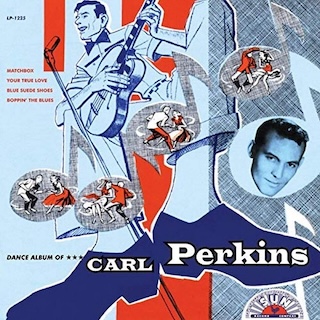

Only now, ahead of next year’s 70th anniversary marking the release of “Blue Suede Shoes,” are the complete sessions seeing the light of day, fittingly on the revitalized Sun Records label under the aegis of New York-based music and media company Primary Wave. Seven new Perkins songs and three covers comprise an album titled Some Things Never Change, after one of the strongest of the original numbers, and bearing a cover design reminiscent of Carl’s only Sun album, 1958’s Dance Album of Carl Perkins (a collection of singles and B sides issued after Carl left the label).

So what happened in 1990? How did it all end with such finality as to confine these recordings to a DAT in Bill Lloyd’s personal archive for 35 years? And how did the music finally get a proper release?

***

The sessions, 10 days in Jackson and Nashville, were drama-free: there was back-and-forth about song selection, with Bill Lloyd championing his favorites among the numerous songs Carl offered for consideration, Carl declining Bill’s suggestion that he record Joe Ely’s “I Had My Hopes Up High,” and Carl embracing his sons’ suggestion that he cover a Jimbeau Hinson-penned love song, “Heart of My Heart.” Not incidentally, it was a cost-efficient endeavor given RCA’s funding the Nashville demos, the use of Carl’s home studio, and, not incidentally, Bill Lloyd offering his services gratis. “I did that on my own dime,” he says. “I just wanted to land the gig,” meaning to produce the official album. “I approached it as if I were on trial as much as anything, y’know. The idea was to walk out with something that I could play for Mary Martin, or somebody.”

In Primal Wave’s press materials, Lloyd mentions a goal of aligning Carl’s music with the dominant country radio trend. Elaborating in this interview, he recalled the early ‘90s era harboring “a faction of country music where Radney and I fit in, where Dwight Yoakam was, where Steve Earle was, and the O’Kanes, and the Desert Rose Band, and just a whole batch of acts seemingly outside the genre but part of the genre. So I thought, Well, why not Carl in that same vibe? It’s rockin’ country–that kind of vibe.”

After sending the finished demos to RCA, he recounts, “I just didn’t hear anything. It all went pear-shaped, as the British say. It just languished, and The Judds were leaving RCA, and Ken Stilts was no longer Carl’s manager, and…” His voice trails off. “It was a real disappointment, a moment when you reach for the brass ring and get kicked in the teeth by fate.” Lloyd transferred the recordings to a master DAT, stored it away, and moved on, as did Carl.

‘Some Things Never Change,’ Carl Perkins, title track from his rediscovered, previously unreleased 1990 album

Cut to the present day and to a fellow named Ben Vaughn, a true multi-hyphenate phenom as a solo artist, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, producer, composer and syndicated radio host, likely best known to the general public for his music for hit TV shows such as Third Rock from the Sun and That ‘70s Show, among many others. A few years back, he and Bill Lloyd convened for a songwriting session, during which Lloyd shared his account of the shelved Perkins project. Vaughn, well versed in music history himself, subsequently got involved with Primary Wave. While working on the company’s 70th anniversary Sun anthology (curated by Chris Isaak), he mentioned the hibernating Perkins album to his colleagues, contact was made, a deal was struck, Stan Perkins gave it the family seal of approval, and Some Things Never Change ended three-and-a-half decades of tender loving care in Bill Lloyd’s possession.

‘Memphis in the Meantime,’ written by John Hiatt, covered by Carl Perkins on Some Things Never Change

Of the finished product, Lloyd offers: “We’re not talking about Bad Bunny and TikTok. We’re talking about music for the ages, but my generation is about the only one that remembers a lot of it. I don’t believe there’s any sense of a huge amount of sales here, but it is important for the people who care about this kind of music. The young crew at Sun is really passionate, they know their stuff, and they’re doing a lot of good things to make hay while they can.”

So what’s it all about? It’s all about what might have been, this missing link in the Original Cat’s recording history: Some Things Never Change might well have altered Carl Perkins’s disappointing late career trajectory, as sure as American Recordings did for Johnny Cash. Given Carl’s hard-luck odyssey, that’s a very big might. But these sessions did showcase his best writing and most soulful performances since the aforementioned My Kind of Country, about which something Carl said in an interview for his biography also applies to Some Things Never Change, to wit: “Most of the things I wrote touched on my own soul. I’m roamin’ around in those songs.”

Consider a few highlights of Carl Perkins “roamin’ around” on Some Things Never Change:

‘Miss Muddy,’ arguably the wildest vocal Carl ever recorded outside of his most bizarre Sun side, 1957’s ‘Her Love Rubbed Off.’ Featured on Some Things Never Change.

“Miss Muddy”—One of the hardest, rawest blues Carl ever recorded, featuring a solid workout on the 88s from Joe Schenk. Deeply invested in his love song to the Mississippi River (a body of water that had a major impact on Carl’s childhood when it overflowed its banks in Tiptonville, TN, and forced the Perkins family to run for their lives in the dead of night), Carl is growling at points, rising to a fragile upper register howl at others, and dropping into a talking blues mode as the song winds down—it’s arguably the wildest vocal he ever recorded outside of his most bizarre Sun side, 1957’s “Her Love Rubbed Off,” which Carl laid down in an all-night Sun session during which, by his own admission, “we were all pretty high.”

“Where Does Love Go”—if “Miss Muddy” belongs in the upper tier of Carl’s rawest performances, “Where Does Love Go” ranks among his most tender laments over lost love, comparing it to the turning of the earth as the seasons change while wondering how certain monuments remain curiously untouched over time. Sweetening the deal, Carl accompanies his musings with understated, Les Paul-indebted fingerpicking, acoustic in effect, solemnly enhancing the wounded wonder his lyrics convey.

“Some Things Never Change”—A warm love song, quintessentially sentimental Carl, marveling at the persistence of love in a bright, chirpy melody betraying a Lennon-McCartney lilt, set in a soothing ambience defined by Joe Schenk’s sensitive piano fills and Carl’s rich but economical guitar solos.

“Memphis In the Meantime”—John Hiatt’s rock ‘n’ roll steamroller celebrating the Bluff City’s style and allure, with an Elvis echo in the fleeting “Mystery Train” lick in Carl’s opening guitar solo before the proceedings become a driving rhythm attack fueled by Carl’s extended spitfire guitar soloing underpinning his wry vocal delivery. A good-time, rockabilly conflagration, this, and a meaningful moment for Carl personally, even if he didn’t write the song.

‘Messin’ Around with Rock ‘n’ Roll,’ Carl Perkins, from Some Things Never Change

“Messin’ Around with Rock ‘n’ Roll”— A thoroughly greasy romp that lyrically tracks perfectly with Carl’s story of creating music that had no name when he first walked into the Sun studio in 1954. Consider this a sequel to one of Carl’s finest post-Sun songs, “The Birth of Rock & Roll,” written for the 1986 reunion with Cash, Jerry Lee, and Roy Orbison issued as Class of ’55. The real story is the energy emanating from Carl’s singing, along with his richly textured guitar work (single note runs, double stops, alternating bursts of syncopated upper and lower neck punctuations)—the Original Cat in full flower.

“Baby, Bye Bye” Kicking off with another “Mystery Train” lick, this stinging rockabilly workout emphasizes Carl’s indebtedness to the blues.

Given all the missteps and misfortunes in Carl’s career, the title Some Things Never Change is rich in irony. But the power—and the truth—of its performances at least takes some sting out of being kicked in the teeth by fate.

Carl’s only Sun album, released in 1959, after he had left the label for Columbia Records