Maria Muldaur: She’s made the repertoires of the distaff blues singers a vital part of her identity from the time she first set foot on a stage or in a recording studio.

By David McGee

ONE HOUR MAMA: THE BLUES OF VICTORIA SPIVEY

Maria Muldaur

Nola Blue (released July 11, 2025)

Maria Muldaur holds an almost singular place in contemporary blues in devoting so much of her career to honoring the great female blues singers who preceded and influenced her. In 2001 she stirred the pot with Richland Woman Blues, a tribute to Memphis Minnie, Bessie Smith, and Mamie Smith; in 2005 she offered an entire album tribute to Memphis Minnie on Sweet Lovin’ Ol’ Soul; in 2012 she paid Minnie another tribute on …First Came Memphis Minnie; and in 2007 she surveyed the ribald side of blues from the ‘20s to the ‘40s in Naughty, Bawdy and Blue in songs associated with Alberta Hunter, Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, Sippie Wallace, and Ms. Spivey. Maria, along with Rory Block (with her Mentor Series tributes to the great male blues masters she knew and learned from), are pretty much on this trail alone.

In short, the lives and music of pioneering distaff blues singers has been a vital component of Ms. Muldaur’s vital part of her identity from the time she first set foot on a stage or in a recording studio. Let the rest of the world genuflect at the altars of Disney-trained pop tarts; Maria Muldaur sings of mature women and their inner lives and lusts. In some of these endeavors she’s been backed by James Dapogney’s Chicago Jazz Band, as she is on three tunes on this new tribute to a woman without whom there might not be the Maria Muldaur we’ve known since the ‘60s, namely one Victoria Spivey. Growing up in Greenwich Village, the young Maria Grazia Rosa Domenica D’Amato was drawn to her fellow Village resident and performer, Ms. Spivey, at the outset of her professional career. The liner notes for One Hot Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey recount the deep influence Ms. Spivey exerted on Maria’s entire approach to the professional musician’s life. And why not? Victoria Spivey was no mere blues singer, as Dr. Warren Davies documents in liner notes he penned for the Journal of Jazz Studies and reprinted in One Hour Mama, to wit:

She was, at one point or another: a bar room pianist, a top selling “race” recording artist, a staff composer for a music publishing company, one-half of a vaudeville double-act, a Hollywood actress, a church music director, a record producer and label owner [Ed. Note: she was the first to record Bob Dylan], a booking agent, and a jazz critic.

Victoria herself, in a column she wrote for Record Research in 1964 (Issue #63, also reprinted in the liner booklet), recalled her first impressions upon meeting young Maria, who was then playing in “a certain revival jug band”: “I studied her voice, her looks, and her personality very well. I can tell you that I found nothing but success for this little lady. I called her aside and told her to go for herself and to find a spot in which she could show off her talents instead of being in the background.”

‘My Handy Man, written by Andy Razaf; Maria Muldaur, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

’T-B Blues,’ written by Victoria Spivey; Maria Muldaur, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

From the short-lived Even Dozen Jug Band to the Jim Kweskin Jug Band to her duo with (and marriage to) Geoff Muldaur to the celebrated start of her solo career with “Midnight at the Oasis” on to the present day, Maria has followed Ms. Spivey’s advice to “go for herself,” and we the fans are the beneficiaries of that sage dictum. Case in point, Maria’s latest album (released in 2025), a full-on tribute to her mentor in a mere dozen songs (seven written or co-written by Ms. Spivey) with the singer backed by three different groups so steeped in the sounds of Spivey’s prime years as to seem as if they plunged through a time warp fresh from the Roaring ‘20s. Three of the songs feature James Dapogney’s Chicago Jazz Band, an aggregate familiar to Muldaur’s fans. This lively outfit gets down and dirty behind Maria on Andy Razaf’s “My Handy Man,” a delightfully lusty double-entendre litany hinting at pleasures of the flesh first popularized by Ethel Waters in her secular incarnation and reprised here from Maria’s Naughty, Bawdy and Blue album. Then there’s the title track, a slow, swaggering come-on written by Porter Grainger and recorded by Spivey in 1937, in which the female protagonist credibly yearns for a 60-minute man. Spivey’s 1926 deep blues, “T-B Blues,” blurs the line between real, debilitating illness of the body and existential illness stemming from the social stigma connected to the disease, underscored vocally by Maria’s a lowdown, ominous reading, her voice deep and despairing, seemingly accepting of consumption’s creeping, agonizing toll. “T-B Blues” was also featured on Naughty, Bawdy and Blue.

‘What Makes You. Act Like That,’ written by Lonnie Johnson; Maria Muldaur and Elvin Bishop, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

‘Any-Kind-a-Man,’ written by Hattie McDaniel; Maria Muldaur, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

One of the album’s most striking tunes finds the singer ably supported by the lineup featured on seven of the dozen tunes, including swinging guitarist Danny Caron, saxophonist Johnny Bones, bassist Steve Height, pianists Neil Fontano and David K. Mathews, and drummer Beaumont Beaullieu. One of many highlights with this configuration comes early in a freewheeling version of Lonnie Johnson’s comedic take on diva behavior, “What Makes You Act Like That,” wherein male and female characters air their grievances against each other, with the male voice being supplied by Elvin Bishop, strikingly weathered and weary and a bit perplexed to boot, as Maria continues the dialogue in convincing fed-up mode, all to hilarious effect. Arguably Maria’s finest performance here is with this lineup on Spivey’s tortured, self-explanatory slow blues, “Don’t Love No Married Man,” with a pronounced noir-ish ambience supplied by Johnny Bones’s dark sax rumblings and guest Chris Burns’s mournful piano. With so many themes of disappointment and deceit informing these songs, some sunshine does break through the clouds, impressively so when it appears. Consider Maria’s cheery, vulnerable vocal (with a dip into her lower smoky register to coo, “‘cause I love you” here and there) on Spivey’s “Dreaming of You” recalls the lighthearted flight she took on “Midnight at the Oasis.” The biggest surprise among the song selections is the swinging kissoff blues, “Any-Kind-a-Man,” another instance when the pianist’s ragtime-influenced jaunts add a buoyant lift to the singer’s rather cheery adieu to a feckless fellow, “‘cause any kinda man is better than you.” Recorded by Spivey in 1936, “Any-Kind-a-Man” is notable for its original 1926 recording by none other than the woman who wrote it, Hattie McDaniel, more than a decade before she became the first African-American actress to win an Oscar, so honored for her role as Mammy in Gone With the Wind. McDaniel recorded only 16 sides between 1926 and 1929 and is widely credited with being the first black woman to sing on radio in the U.S., but her recording career is only a footnote to her work in film. Nice touch to add her to the mix and with a Spivey connection to boot. And let’s not discount the incredible chemistry between Maria and Taj Mahal on a 1930 Spivey co-write with Harold Grey (aka Porter Grainger) on “Gotta Have What It Takes,” a hokum-style set-to with Taj firing back witty retorts to Maria’s potshots at his masculinity and commitment (or lack thereof). For instance:

Maria: I’m full of pep—

Taj: Oh you is?

Maria: I’m afraid.

Taj: Afraid of what?

Maria: You are so old/you can’t make the grade.

Taj: Oh yes I can!

Maria: You got to have what it takes.

Taj: I got this, baby!

It’s a great moment on the album, and between Maria, Elvin, and Taj, the senior citizens performing on One Hour Mama set a high bar for the relative youngsters backing their efforts.

‘Gotta Have What It Takes,’ written by Victoria Spivey and Harold Grey; Maria Muldaur and Taj Mahal, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

‘Organ Grinder Blues,’ written by Clarence Williams, recored by Clarence Williams, Victoria Spivey, and Ethel Waters in 1928; Maria Muldaur, from One Hour Mama: The Blues of Victoria Spivey

The New Orleans sound is familiar territory for Maria, and she returns to it here twice, on “Funny Feathers” (a 1929 co-write between Spivey and Reuben Floyd, one of Spivey’s four husbands), a lighthearted tale of a “chicken clown” who’s “the best dressed rooster in town” and the effect he has on the “chicks…who call him pa.” The musical backdrop is a raucous clarinet-trombone-tuba-piano-driven attack by Tuba Skinny (featured on Maria’s 2021 Let’s Get Happy Together album), who give Maria that celebratory Crescent City swing in supporting her warm approach; on the Clarence Williams-penned melding of blues and jazz on “Organ Grinder Blues” (recorded in 1928 by the Clarence Williams Orchestra, Ms. Spivey and Ethel Waters alike) the same lineup dips into a more ruminative mode, appropriately injecting the je ne sais quoi to underpin Maria’s low moaning, lower-register dips bringing unusual sizzle to lubricious observations such as “if you’re tired, let mama grind a while for you” and “it’s not the organ but the way you grind,” with Shaye Cohn’s suggestive trumpet fills fleshing out, so to speak, the lyrics’ intent.

The past is not prologue in this artist’s hands. It’s the stuff of life. This One Hour Mama is timeless.

More Maria Muldaur coverage in Deep Roots

“Something Old, Something New, Lots of Blues”

Review of …First Came Memphis Minnie

“Shimmying Down the Chimney”

Review of Christmas at the Oasis

Review of Let’s Get Happy Together

***

Johnnie Johnson: ‘They call me Johnnie J/and I sure like to play/people, I can’t help myself, I guess I was just born that way…’

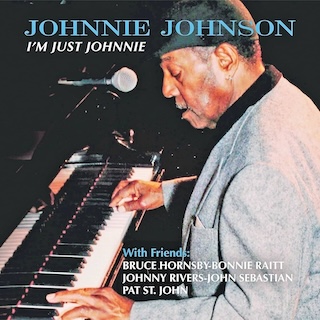

Just Johnnie? How About The Johnnie?

By David McGee

I’M JUST JOHNNIE

Johnnie Johnson

Missouri Morning Records (released 08-29-2025)

The late, great Johnnie Johnson holds the distinction of being a musical artist many have heard but may well have never heard of. He’s the versatile piano player enlivening many of Chuck Berry’s hits over the first two culture defining rock ‘n’ roll decades of Chuck’s career. Millions heard and bought those records but fewer of Chuck’s fans heard Johnnie Johnson as an in-demand accompanist and band leader at the forefront of the St. Louis blues scene prior to his hiring young Chuck to replace a disabled member of Johnson’s Sir John Trio for a New Year’s Eve gig to ring out 1952, and later, in the ‘80s, as a member of the St. Louis-based The Sounds of the City and as an accompanist for other blues artist passing through the Gateway City. Not the least of Johnnie’s honors: his Congressional Gold Medal, awarded posthumously in 2019 for his WWII service as one of the first African-Americans to serve in the Marine Corps as part of a group of black recruits trained at Camp Montford Point in Jacksonville, NC, now memorialized by the nonprofit Montford Point Marine Association (MPMA).

After parting ways with Chuck in 1973, Johnson continued working with other artists’ bands (including a lengthy tenure backing Albert King) until reuniting, briefly, with Chuck for the Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll concert film in 1987, after which Johnnie recorded his first solo album, Blue Hand Johnnie, and spent a few fruitful years backing some of the 20th Century’s blues greats and blues-steeped rockers of his time (including Keith Richards and Eric Clapton). In late 2004, he returned to St. Louis to record another album, Johnnie Be Eighty. And Still Bad!, containing all-new original songs co-written with producer Jeff Alexander. The album was released in 2005, in the same week Johnny died of a kidney ailment.

‘School Days,’ Chuck Berry with Johnnie Johnson on piano (1957)

‘Wee Wee Hours,’ Chuck Berry with Johnnie Johnson on piano (1955)

However, there were other sides in the vault from sessions recorded in 2003 and 2004, a dozen songs at least, with a few being Johnnie Johnson originals, and featuring a number of high-profile guests making significant contributions to what sound like high-spirited sessions. Thus the content of a most welcome new Johnnie Johnson long player, released last year, titled I’m Just Johnnie, on which he sings some but mostly plays like a man possessed and with a vitality belying his years. Also, humility being one of Johnnie Johnson’s defining character traits, listeners will find him not calling attention to himself but playing exactly what needs to be played and not one note more. He does not shy away from dropping in stride, blues, honky tonk, R&B, and jazz touches in his solos but always serves the song, serves the mood, and always respects what his bandmates have built before he enters the action.

One of those Johnson originals is a co-write with session bassist Dickie Steltenpohl and album produced Gene Ackmann bearing the familiar titled of “Heebie Jeebies,” although it’s far from the like-titled tune from Little Richard’s golden era. This semi-autobiographical swaggering workout recounts how a “stalking woman” sends a man running for the hills whenever she materializes, with Charles Glenn, better known for singing the national anthem for the St. Louis Blues hockey team for the past 19 years, bringing the anxiety-ridden tale to vivid life with a stressed-out vocal reading every bit as hilarious as it is reflective of a man at wit’s end as a robust horn section and a chirping female chorus, along with Johnnie’s boogie-woogie piano, underpin the churning atmospherics. With pumping horns and a strutting rhythmic attack, Johnnie kicks off the long-player with the title track, an original ode to self-reliance co-written with producer Ackman again, in which Johnson makes his only reference to his tenure with Chuck when he sings, “I’m just Johnnie and I’m trying to be good” (this, despite Johnnie insisting over the years that he was not “Johnny B. Goode” nor did he have any part in the song’s creation, no matter that Chuck declared it to be a tribute to Johnnie well after its release). On Johnnie’s grinding slow blues about a fellow putting his romantic travails behind him, “I Get Weary,” his right-hand rolls and trills on the 88s gain some oomph from Paul Willett’s humming B3 and set the stage for the late Max Baker’s searing guitar solo that explodes off the track like the buried anger it seems to articulate.

‘Heeby Jeebies,’ Johnnie Johnson with lead vocalist Charles Glenn, from I’m Just Johnnie

‘Let the Good Times Roll,’ Johnnie Johnson, with co-lead vocal by Bruce Hornsby, and Bonnie Raitt on slide guitar, from I’m Just Johnnie

On the old warhorse “Every Day I Have the Blues,” the rhythmic sprint is fueled by Johnnie’s romping across the keys and lively vocals by Johnnie and Bruce Hornsby that recede a couple of times to accommodate ferocious howling slide guitar sorties courtesy Bonnie Raitt in high dudgeon. Ms. Raitt and her slide guitar return later on a seriously stomping workout on “Let the Good Times Roll,” responding to vocalist-drummer Kenny Rice’s directive to “play the blues, Bonnie!” with an aggrieved howl, as heated as it is penetrating, which in turn sets up Johnnie for a frolic on the keys, with Bonnie returning near song’s end to support the assembled chorus’s shouted title sentiment (out of the seven voices, you don’t even have to listen closely to hear Bonnie’s ebullient contribution rise above the others) with subtle slide punctuations goosing the party along to its celebratory conclusion. The Raitt profile expands exponentially on this project’s second disc featuring interviews with Johnnie conducted near the end of his life by the veteran rock DJ (and Radio Hall of Fame inductee) Pat St. John, which also feature Bonnie offering her perspective on Johnny’s legacy.

‘Let the Good Times Roll,’ Johnnie Johnson, with co-lead vocal by Bruce Hornsby, and Bonnie Raitt on slide guitar, from I‘m Just Johnnie

‘Broke the Bank’ Johnnie Johnson, with John Sebastian on harmonica, Tom Maloney on guitar, Gus Thornton on bass, Kenny Rice on drums, from I’m Just Johnnie

On another rocking Johnnie original, “Broke the Bank,” fueled by Johnnie’s frisky, trilling right-hand runs and driving percussion (the tune kicks off with cannon shots from Kenny Rice’s drums), none other than John Sebastian bursts in with a muscular harmonica solo of the sit-up-and-take-notice variety, complementing Johnnie’s personable baritone vocal before guitarist Tom Maloney and the pulsing horn section bring it all home in a boffo finale. Making a significant contribution above and beyond the call of duty, Johnny Rivers appears twice, both times on new songs he wrote for this project and on which he plays guitar. The bluesy “Lo Down” gets an appropriately disconsolate, retaliatory (against the woman who done him wrong) lead vocal by Henry Lawrence, better known to the general public as a former Oakland Raiders All-Pro offensive tackle, albeit one able to pack a punch vocally, with Rivers offering howling interjections along the way before meshing with the horns at fadeout. Another new Rivers tune, “Johnnie Johnson Blues,” a swaying, laid-back 12-bar blues, finds Johnnie in mission statement mode, with Johnnie, via the Rivers lyrics, stating for the record (no pun intended) something vital he’s learned in his time: “They call me Johnnie J/and I sure like to play/people, I can’t help myself, I guess I was just born that way/I don’t like to travel and I don’t like to roam/I just want to stay here, ‘cause St. Louis is my home/I don’t want to be a lawyer, I can’t do no income tax/I just want to play the blues…I don’t want no woman telling me what to do/I might just want to stay out all night long, or I might just want to make love to you…” A stop-time pause ensues at the 3:44 mark before Johnnie breaks into boogie-woogie mode romping with the band through the track’s last 90 seconds.

‘Johnnie Johnson Blues,’ written by Johnny Rivers, vocal by Johnnie Johnson, with Rivers on guitar, Gus Thornton on bass, Kenny Rice on drums, from I’m Just Johnnie

‘I’m Just Johnnie,’ a Johnnie Johnson-Gene Ackmann original, with Johnnie on piano, Tony T on guitar, Gus Thornton on bass, Kenny Rice on drums, Jim Manley on trumpet, Ray Vollmar on sax, from I’m Just Johnnie

All the guest artists make their mark when called upon, but the big tip of the hat should go to the basic band behind Johnnie in various configurations on these 2003-2004 sessions, all tight, lively, inspired, and perfectly attuned to the repertoire’s moods and energy. Hardly the best-known names here, are these, but apart from Johnnie himself, they are most responsible for letting the good times roll from start to finish. Six of these musicians have since passed away, including Max Baker (guitar), Bob Hammett (guitar), Andy O’Connor (drums), Tony T (guitar), Gus Thornton (bass), and Larry Smith (baritone sax). Two long-time members of Johnnie’s band, who also worked with Johnnie backing Albert King, stand out as well, these being drummer-vocalist Kenny Rice and bassist Gus Thornton, who form the powerhouse rhythm section on most of the cuts here (Mr. Thornton “left mortality to immortality” on November 13, 2024, according to an obituary posted at Serenity Memorial). And not least of all, kudos to producer Gene Ackmann for a great job behind the board and also for befriending Johnnie, helping him realize his dream of making a new album (logistically, financially and otherwise), co-writing some new mtunes with him, and generally insuring this legacy moment would stand the test of time for an artist who used his gift honorably in service to many other important artists, was a gentleman, performed heroically in service to his country in wartime, and is enshrined as an important component in post-war America’s cultural revolution.