Double Dynamite: Mike Zito (left) and Tinsley Ellis, two Deep Roots 2024 Albums of the Year winners, playing the blues in Boston

As our regular readers know, Deep Roots has a different approach to year-end accolades. Given our broad definition of roots music, we’ve never limited our best-of lists to, say, one Album of the Year and/or a Top 10 best of the rest. No, our best-of lists reflect our opinion of the best of the genres we cover: blues, traditional country, bluegrass, World Music, jazz, Classical (also broadly defined), classic pop, early rock ‘n’ roll-soul-R&B-group harmony-doo-wop. Our the course of our 16-going-on-17-year history (starting as TheBluegrassSpecial.com, transitioning to Deep Roots in September 2012), we’ve anointed anywhere from five to 10 long-players as our Albums of the Year. This list is then supplemented by the Deep Roots Elite Half-Hundred, this being 50 albums across all the genres that we found most meaningful, most lasting.

This year’s Albums of the Year selections reflect a 2024 in which several artists near and dear to our hearts issued deeply personal albums, milestone albums in some cases marking significant career or personal inflection points. Our #1 album, for instance, Mike Zito’s Life is Hard, is the blues-rock titan’s first album since the July 2023 passing of his beloved wife Laura and his subsequent struggle to stay whole while coming to grips with the magnitude of his and his family’s loss. Blues harmonica veteran Corky Siegel, who has spent the bulk of his long career working (as both composer and instrumentalist0 at the nexus of blues and classical music, issued what appears to be the final chapter of the 81-year-old harmonica master’s efforts to mate blues and classical in Corky Siegel’s. Symphonic Blues No. 6, a composition that has been performed in concert for years and now finally makes it onto disc. Acclaimed classical violinist Daniel Hope, born in South Africa but exiled with the rest of his immediate family in the early 1970s, ultimately winding up in London, is descended from an Irish family that migrated to South Africa in the late 1800s. To Ireland the exiled family returned, and Daniel grew up learning of his forebears’ Irish roots (“That background was always present,” he says) and developing a deep love of Irish music. So 2024 brought us Daniel Hope’s impassioned tribute to his family history in the form of Irish Roots, a survey of not only great Irish music of the past (Turlough O’Carolan, for instance) along with classical pieces by non-Irish composers whose compositions helped introduce the influence of music from other lands into the Irish musical culture. Hence, Daniel Hope’s Irish Roots. Eric Bibb, who for years has been exploring social justice issues as expressed in folk music from here and abroad, went way inward on In the Real World, charting a more personal journey in his songs while at the same time offering both spiritual and existential guidance. The same can be said of singer-songwriter James Talley, who embraces topicality on his Bandits, Ballads and Blues, a beautiful collection of Talley originals reflecting on everything from the plight of Vietnam veterans, that of an immigrant child, that of a world in chaos, and not least of all, of his own heart’s passion for his loved ones. Talley, now 81, says the album will be his last; if so, it would certainly cap a distinguished and transformative (in that his trio of late ‘70s albums helped steer country music away from its woeful Urban Cowboy fad) career, but we’re hoping he’s fooling.

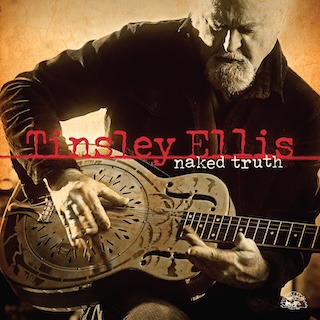

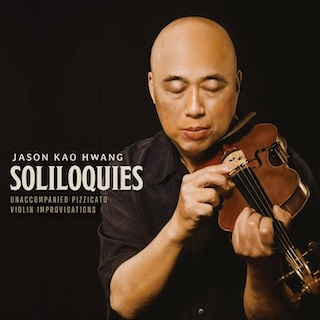

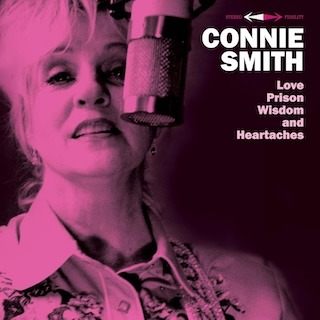

Otherwise our list includes the most pleasant surprise of 2024 in the emergence of Lance Cowan, heretofore known in the music business as publicist to some pretty fair singer-songwriters such Michael Martin Murphey, Guy Clark, the individual Flatlanders and others, immediately took his place among our time’s finest singer-songwriters with his well-crafted, acutely observed and beautifully told character portraits comprising his debut album, So Far, So Good. Another extraordinary singer-songwriter, Regina Vandereijk, emerged with a stunning Christian gospel EP, Love Called Her Home, a frank, unflinching song cycle telling of her journey from a depraved life to spiritual salvation. A North Carolina native now married and living in the Netherlands and partnering with her husband Willo in a discipleship school called Royal Increase. The poetry of her original songs and the startling power of her singing voice—both in its sensitive ballad mode and in the house wrecking quality of her bluesy belting mode (which brooks favorable comparison to that of Wynonna Judd)—is the stuff of an artist who will be heard. Her debut album is due on January 24 and it should be an Event. Then we have two veterans who made major statements in 2024: blues-rocker Tinsley Ellis, delivered Naked Truth, a long-awaited gem: deep, potent acoustic blues, featuring Ellis, his lived-in voice, his 1937 National Steel O Series guitar, his 1969 Martin D-35 and percussive flourishes provided by his clapping hands and stomping feet; and Connie Smith, at 82 continued the recent octogenarian juggernaut on record, aided by the spot-on production of husband Marty Stuart, with the impeccable backing of his Fabulous Superlatives. Connie confidently assays a dozen tracks–including “The Other Side,” her lacerating, self-penned steel- and honky tonk piano-drenched missive addressing a two-faced paramour, recorded in 1965 on her first studio album–drawn mostly from ‘60s contemporaries such as George Jones (the bonafide heartbreaker, “Beneath Still Waters”), Loretta Lynn (“World of Forgotten People”), even Perry Como (“Seattle”). And with something completely different, consider Jason Kao Hwang’s Soliloquies, a mesmerizing album of unaccompanied pizzicato violin improvisations, best described in Scott Currie’s liner notes as a unique accent distinguishing [the artist’s] musical idiom, one that expresses the challenge of speaking one language through another, while giving voice to the aesthetic life history that shaped it. Indeed he does, packing his work with so much cultural, psychological and emotional density in spare formulations in which even the sound of silence carries the weight of ages.

So welcome to the Deep Roots Albums of the Year honorees for 2024. The forthcoming Deep Roots Elite-Half Hundred for 2024 contains a wealth of music that made the year memorable across multiple genres and out of the mainstream music press’s narrow gaze. Please check it out. -–David McGee, January 8, 2025

***

1. LIFE IS HARD, Mike Zito (Gulf Coast Records)

1. LIFE IS HARD, Mike Zito (Gulf Coast Records)

It’s not often that an artist leaves as graphic and intimate a record of his trials, tribulations and tragedies, along with the jubilant moments, as Mike Zito has been doing since February of 2013, when he published the first installment of Mike Zito, A Bluesman in Recovery, a personal online blog. It begins in his tenth year of recovery from debilitating drug and alcohol addiction, chronicles the lifesaving love and commitment of his wife Laura, charts the upward progress of his career in his sobriety, and details the highs and lows of the fight he, Laura and their children fought against cancer’s merciless advance following her diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Now having released Life Is Hard, his first new album since Laura’s passing in July 2023, it seems instructive to appraise the new work in light of the entire journey it encompasses, from the triumph of hard-won sobriety (which informed his gritty, unvarnished 2013 confessional masterpiece, Gone to Texas, a Deep Roots Album of the Year) to the onset and progression of Laura’s illness right up to her final breath. For that we turn to the blog. At least in the music world there’s nothing quite like it, and so let us weigh the backstory, as told in Zito’s own words, against what he, working with producers/guitarists Joe Bonamassa and Josh Smith, has wrought in his first in-depth musical statement since losing Laura. …

‘Without Loving You,’ a Mike Zito original from Life is Hard

Not that you, dear reader, need to know all this background in order to appreciate what Mike Zito delivers on Life Is Hard, blessed as he is with the empathetic support from Bonamassa, Smith and the gifted musicians accompanying him on 11 tracks (12 if you count the radio edit of “Forever My Love,” two minutes shorter than the unabridged version featured earlier). But it would be fair to say the unadorned confessions he’s shared publicly for the past 11 years give the attentive listener a, oh, panoramic appreciation of the depth of feeling Zito conveys in 54 minutes, five seconds of nothing less than the truth of his interior life. For your faithful friend and narrator, only two albums compare to Life Is Hard in all respects: the late, great Joe South’s 1975 masterpiece, Midnight Rainbows, which I reviewed for Rolling Stone upon its release and which haunts me still, given how South’s unsettling songs were penned in the wake of his brother Tommy’s suicide and I was appraising it at a moment when the memory of my own brother’s death a few years earlier, in the prime of his life, was still fresh in my memory; and Dale Watson’s Every Song I Write is For You, from 2001, a touching, string-drenched but often jubilant outpouring of love and loss following his fiancée Terri Smith perishing in a car crash. The tragic accident sent Watson spiraling into an abyss of drug and drink, only to regain his footing–and his soul–through his music. That the songs often have an upbeat quality (Watson has said the original numbers are his love letters to Terri) only deepens the tragedy shadowing them.

Follow this link to the full review, ‘The Knight of Faith,’ by David McGee in Deep Roots

***

2. CORKY SIEGEL’S SYMPHONIC BLUES NO. 6, Corky Siegel (Dawnserly Records)

Community funding has allowed Symphonic Blues No. 6, otherwise performed live all over the world to great acclaim, to be preserved on disc at last. It’s a different approach to what is arguably the most affecting of all Siegal’s blues-classical hybrids. Seventeen musicians are employed, a dozen being symphonic players, with the Chamber Blues Ensemble members rounding out the lineup (Dr. Jaime Gorgojo, violins; Chihsuan Yang, violins; Jocelyn Butler Shoulders, cellos; Allegra Montenari, cello; and Jeff Yang, violas). From there it really gets interesting: the musicians were all recorded separately, with no reference to the music in any way aside from their own part and tempo markings. “Therefore,” Siegel writes, “each part is a solo part and each performer a soloist throughout the whole work. My style of composition incorporates extreme dynamic markings on almost every note of the part to help ensure expression. Our mixing guru Ken Goerres and the rest of the production team agreed that we didn’t want to try replicate a symphony orchestra. That would be limiting. We just wanted to do whatever we could to create a magnificent sonic experience.”

Movement I: Filisko’s Dream, from Corky Siegel’s Symphonic Blues No. 6

When absorbing the whole of Symphony Blues No, 6, reflect for a moment on how American music has been enriched over time by folk and blues meeting up with classical music. Think of Antonìn Dvorák and George and Ira Gershwin. Think of Mark O’Connor and his past 30 years of creating and promoting a new American classical style with a roots music foundation. Listen closely on this album to Movement I: “Filisko’s Dream” and you might hear a fleeting quote from Aaron Copland’s evocation of southwestern wonders. Thus the company in which Siegel, now 81, finds himself on the incredible and fruitful journey that began so inauspiciously when he crossed paths with Seiji Ozawa at Big John’s club in Chicago in 1966. If this be the final recording of Corky Siegel’s remarkable career, then know it as a masterpiece of concept and execution in which elevated technique serves the greater purpose of elevating harmony—musical, inner, social–in the hearts of all who listen. Follow this link to the full review, “Elevating Harmony,” by David McGee in Deep Roots.

***

3. IRISH ROOTS, Daniel Hope (Deutsche Grammophon)

Ireland flows through Daniel Hope’s blood courtesy of his paternal great-grandfather, who left his home in the seafaring city of Waterford in the 1890s to build a new life in South Africa. Daniel McKenna gave his great-grandson his name. The music of Ireland, from barroom reels and country jigs to concert pieces that captivated audiences in Dublin and beyond, also runs deep in the violinist’s soul. Released on 5 July 2024, his latest Deutsche Grammophon album, Irish Roots, takes the listener on an expedition of discovery filled with familiar landmarks, creative adventures and musical surprises.

One of the most popular and frequently recorded traditional fiddle tunes, ‘Red Haired Boy’ is the English translation of the Gaelic title ‘Giolla Rua’ (or, Englished, ‘Gilderoy’), and is generally thought to commemorate a real-life rogue and bandit. Throughout the British Isles the song was quite common under the Gaelic and the alternate title ‘Little Beggarman (The)’ (or ‘The Beggarman,’ ‘The Beggar’). However, in Scotland the ‘Beggar’ of the title is also identified with King James V. Daniel Hope’s version is included on Irish Roots.

Although Hope has never lived in Ireland, he cherishes the place that provided him and his stateless family with citizen status almost half a century ago, after they were forced to leave South Africa to seek political asylum. His fascination with its culture and family tales of the old country led him to make a documentary for ARTE and WDR entitled Celtic Dreams: Daniel Hope’s Hidden Irish History, first aired in spring 2022. He also began exploring the connections between folk and classical music in Ireland, supported by musicologist Olivier Fourés and performance experiences with award-winning Irish band Lúnasa.

Follow this link to the interview with Daniel Hope in Deep Roots, courtesy Deutsche Grammaphon

***

4. IN THE REAL WORLD, Eric Bibb (Stony Plain)

In a career entering its sixth decade, Eric Bibb is in top form. 2023’s Grammy-nominated Ridin’, April’s Live at the Scala Theatre, and 2021’s Dear America all proved essential and edifying. In the Real World is no exception. Like Ridin’, it contains 15 songs spanning an hour. Bibb and longtime musical partner Glen Scott (producer, arranger, and multi-instrumentalist) helmed the sessions at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios with an international cast of collaborators that includes a string quartet, a fiddler, a gospel-inspired backing chorus, and a guest spot by actress/vocalist Lily James.

‘Got to change the way we take for granted all the gifts/all the gifts Mother Nature provides…Wanna see a change in the world/make a change in you”—’Make a Change,’ Eric Bibb, from In the Real World

The album is poignant, alternating between tension, narrative reflection, and hope. “Taking the Stage” is the opening (and longest) track here. While the song’s melody and lyrics are pure Bibb, it reflects the influences of Mississippi John Hurt and Taj Mahal. Part folk song, part spiritual, part blues, Bibb’s protagonist reflects on the world of the present: burning, crumbling, violent, filled with fear, pain, and rage, but he also points to a new world of freedom emerging. Bibb’s fingerpicked acoustic is backed by electric slide, B-3, and gentle backing vocals. “Walking Steady On” is a spiritual blues. Bibb’s banjo and steel strings are backed by thudding kickdrums, tom-toms, and organ. He references trouble in the present before the “fire next time” that arrives to tear the world asunder. His exhortation to …”keep walkin’ in the gospel way,” is the path to the new world referred to in the previous song. “Best I Can” is a sparse folk-blues delivered with canny melodic skill and a subtly arranged string section. “Everybody’s Got a Right” and “Make a Change” are drenched in country/urban blues and rhythms, with entwining guitars –acoustic, electric, and slide–underscoring the prophetic authority in Bibb’s vocal. “This River” is a haunted gospel-blues showcasing Esbjörn Hazelius’ fiddle and a soulful women’s chorus ad libbing. “Stealin’ Home” is a sung blues narrative about Jackie Robinson. “If There’s Any Rule” is a lithe, rocking, Americana tune; the lyric is painted by a marching snare, Hazelius’ fiddle, Robbie McIntosh’s resonant slide guitar, and a faraway piano. Its message, “If there is any rule we’re born to follow/It’s love each other/If any rule is gonna guarantee tomorrow/It’s love.…” … At once poignant and hopeful, Bibb has upped his own creative ante here. Follow this link to Thom Jurek’s full review at AllMusic.com

***

5. BALLADS, BANDITS AND BLUES, James Talley (Cimarron Records)– In the mid- to late ’70s, when Nashville was mired in the Urban Cowboy fad, along came James Talley, signed to Capitol Records and thus boasting major label clout, almost single handedly returning the industry to its proper roots with four successive tradition-oriented albums released between 1975 and 1977, which also signaled the onset of the fruitful New Traditionalist movement that would flower in the ‘80s. Even Rolling Stone was hailing him as a savior and heavyweight critics such as Peter Guralnick were extolling his ascendancy and authenticity. Then Talley disappeared until 1985, when he resurfaced on his own Cimarron Records label while making ends meet as a successful Music City real estate agent. In the ’90s, through Cimarron, he continued issuing acclaimed albums rooted in his love of folk, blues, Western swing, all things roots, with 1999’s Woody Guthrie and Songs of My Oklahoma Home being by far the finest of several Woody Guthrie tributes materializing that year. But again, following 2009’s Heartsong, Talley disappeared, resurfacing only this year with what he told The Nashville Scene will be his final album, Bandits, Ballads and Blues. So be it, and if it’s true, he’s going out in style.

‘In These Times,’ James Talley, from Bandits, Ballads and Blues

Trusted friend and longtime collaborator Dave Pomeroy produced, plays bass and leads an all-star Nashville band featuring Doyle Grisham, Jeff Taylor, Billy Contreras, and Mike Nobel (let it be said that Talley has always recorded with the cream of the crop musicians–he’s an artist other musicians love to accompany). The formidable gospel force that is The McCrary Sisters makes its presence felt here too. The album title reveals the stylistic range Talley covers in his songs and has explored throughout this career. A man with a deeply sensitive soul, and a keen sense of social justice, or injustice as the case may be, Talley doesn’t shrink from topicality: “Christmas on the Rio Grande,” for example, examines the plight of an immigrant child in crisis at the southern border. A penetrating perspective on the fate of Vietnam Vets returning to be forgotten informs “For Those Who Can’t,” which is really a song for too many Vets beyond those who served in Southeast Asia. And few contemporary singer-songwriters have addressed a nation in crisis as effectively and poetically as does Talley, with the McCrary women humming deep and low behind him, in “In These Times” (…in these times with crazy all around us/in the times when our reality confounds us/in these times when compassion dies around us/give us strength…) in what might be prayer for someone in his personal orbit–maybe a child–but speaks to the common welfare as well. His voice has aged well and, it can be argued, is at its warmest and most expressive right here right now; but it’s his plainspoken delivery, enhancing his messages in a nuanced, conversational style, that hits with more moral force than any belting vocalist could muster. And when he returns to home and hearth, his tenderness towards his loved ones brings thoughts too deep for tears, as Wordsworth would have it–consider the love overflowing in “The Dreamer,” a tribute to his father, and especially to his wife Jan, in “You Always Look Good in Red.” Here’s hoping his “retirement” is along the lines of Bob Dylan’s Neverending Tour. –David McGee

***

6. SO FAR, SO GOOD, Lance Cowan (Lantzapalooze Müzik)

Veteran Nashville publicist for the likes of Michael Martin Murphey, Nanci Griffith, Guy Clark and the individual Flatlanders, Lance Cowan, having honed his singer-songwriter skills, does nothing less than deliver, in his debut album, one of 2024’s big surprises. Echoes of Steve Goodman, John Prine (especially his first album, when he was little known outside of Chicago and stunned a generation with his vivid, lived-in—and often beautiful—dissections of a world rife with myriad disfunction and alienation among the populace young and old), and Murph, among others, surface in his literate, intimately detailed perspective, but mostly you’ll hear the elevated songcraft common to the best of the New Traditionalist movement of yore set in a soothing string-rich soundscape defined by acoustic guitars, mandolin, pedal steel and fiddle, all pristine as fresh waters.

‘Little Johnny Pierce,’ Lance Cowan, from So Far, So Good

Cowan’s clear, appealing tenor is the voice of a close friend, gently speaking of “the spirit of tender hearts broken/the wish of a falling star/the thunder of a new generation” (“For You”) and telling poignant tales of characters both disillusioned (teenage “Little Johnny Pierce,” who freaked out strait-laced neighbors with his “Lennon glasses” and counterculture lifestyle, only to find, upon being drafted, that talk of “love and brotherhood” wasn’t a simple concept in real life) and worldly wise, namely 93-year-old lifelong farmer “Mr. Ben McGhee” nightly restoring his soul and burnishing his memories with music. And the binding ties of home and hearth beckon, always, underpinning almost every song; this, even though the album title, So Far, So Good, suggests the known unknown—the challenges ahead and how life could change for ill or good in a beat. This one will hit you where you live and stay there for a long, long time. –David McGee

***

7. NAKED TRUTH, Tinsley Ellis (Alligator Records)

Tinsley Ellis, normally fronting a blistering blues-rock juggernaut, has delivered a long-awaited gem: deep, potent acoustic blues, featuring Ellis, his lived-in voice, his 1937 National Steel O Series guitar, his 1969 Martin D-35 (a treasured gift from this father), and percussive flourishes provided by his clapping hands and stomping feet. Of the dozen songs, only three are covers, including a lovingly rendered version of Leo Kottke’s instrumental beauty, “Sailor’s Grave on the Prairie,” complete with those evocative Kottke slide swoops, precision-picked single note lines and poignant melody evoking the feel of an endless horizon. Ellis also burns righteously in covering Son House’s monument, “Death Letter Blues,” delivered in a deep, frighteningly wounded voice spitting out the verses with unalloyed, self-lacerating fury while complementing the horror he experiences with a powerhouse guitar attack alternating between banshee-like slide howls and angry comping. His own songs assay blues styles from the Mississippi hill country (the spooky “Devil in the Room”) to the Delta’s dark heart in the spare Bentonia blues and wounded, upper register 12-bar lamentations of “Windowpane,” with a touch of Robert Johnson’s saucy humor in the lusty bounce fueling “Grown Ass Man”’s come-on. Blues album of the year? You read it here first. –David McGee

‘Death Letter Blues,’ the Son House classic as performed by Ainsley Ellis on Naked Truth

***

8. SOLILOQUIES, Jason Kao Hwang (True Sound Recordings

In his elegant, loving opening statement published apart from Scott Currie’s essential liner notes for Soliloquies, Jason Kao Hwang lays out his mission in poignant terms. To wit: For the children of warm survivors there are conversations with our parents we wish we had and could not. I often wonder about my parents’ vague allusions to atrocities they survived in China during World War II because their trauma was far greater than I can imagine, even now, over twenty years since their passing. In Soliloquies, I honor their courage by embracing their values within mine, to sing into our unknowable silence encircling dreams. I am especially playing for my father, who endured multiple strokes, the last of which took his voice.

‘Bending Branches into Roots,’ Jason Kao Huang, from Soliloquies

Scott Currie’s liner notes, which deserve to be read in full, help listeners understand the complexities and rich history informing Jason Kao Hwang’s artistry. A sampling:

Even across Jason’s vast and diverse body of work, a careful listener can thus discern a unique accent distinguishing his musical idiom, one that expresses the challenge of speaking one language through another, while giving voice to the aesthetic life history that shaped it. In this respect, his professional endeavors to apprehend East Asian musical traditions through his collaborative contemporary jazz conception seem to echo his personal struggles, as a monolingual English speaker growing up in a bilingual Chinese-American household, to make sense of his parents’ musical-sounding conversations, gleaning meaning from words he couldn’t understand by attuning his ears to the native nuances of prosody and rhythm that also accented their adopted English, hinting at deeper meanings otherwise lost in translation.

‘Where the River Runs Both Ways,’ Jason Kao Huang, from Soliloquies

As it happens, the extraordinary pizzicato technique Jason showcases on the recordings at hand harkens back to his earliest attempts–dating from his emergence on the New York scene in the late 1970s–to engage such intercultural dynamics, accompanying choreographer Theodora Yoshikami’s dance productions at Chinatown’s Basement Workshop with his downtown loft-jazz colleague Will Connell by his side. As one can hear in selections like “Silhouettes Lean Forward” or “Bending Branches Into Roots,” the percussive punch of his plucked violin strings could easily send a whole company in motion across the floor, as he shuffles through various rhythm section roles, evoking drummer, bassist, and occasionally even guitarist by turns. At the same time, though, the portamento slides ending the former’s phrases point toward mutually reinforcing African and Asian diasporic resonances, between the sounds of tension and talking drums on the one hand and those of zithers from the gayageum-koto-qin family on the other. Similar pitch-bending portamentos, particularly reminiscent of the Korean gayageum, open “Where the River Runs Both Ways” and define key sections of “Before God.” Bell-like harmonics closely associated with East-Asian zither traditions also end “Hungry Shadows” and punctuate the first section of “Remembering Our Conversation.”

‘Shards,’ Jason Kao Hwang, from Soliloquies

By the same token, dramatic tremolos, characteristic of the Chinese pipa (plucked lute) masters with whom Jason has collaborated, appear prominently throughout, especially the high and fast single-note strumming that launches “At the Beginning,” and “Encirclement,” and lends additional rhythmic impetus to the emphatic tonal-language inflections of “Dreams Dream.” The high transient plucks foregrounded at the beginning and end of “Shards” suggest pipa technique as well, while also sounding like percussive wood blocks or claves, with timbral commonalities pointing back full circle in the direction of another Afro-Asian sonic nexus.

These notes cannot be improved upon as being the most informed guide to Jason Kao Hwang’s powerful statement that is Soliloquies—so much cultural, psychological and emotional density in spare formulations in which even the sound of silence carries the weight of ages. –DM

***

9. LOVE, PRISON, WISDOM AND HEARTACHES, Connie Smih (Fat Possum)

Let’s hear it for the octogenarians! In the past year Sylvia Tyson (83), Jack Jones (86), Taj Mahal (82), Tom Rush (83), James Taley (81) and now Connie Smith (82) have produced some of the most memorable work of their storied careers. Aided by the spot-on production of husband Marty Stuart, with the impeccable backing of his Fabulous Superlatives (along with notable guest appearances by Hargus “Pig” Robbins on the 88s and Gary Carter on steel), Connie confidently assays a dozen tracks–including “The Other Side,” her lacerating, self-penned steel- and honky tonk piano-drenched missive addressing a two-faced paramour, recorded in 1965 on her first studio album–drawn mostly from ‘60s contemporaries such as George Jones (the bonafide heartbreaker, “Beneath Still Waters”), Loretta Lynn (“World of Forgotten People”), even Perry Como (“Seattle”). Stuart couches Connie’s solid, mature vocals—deeply invested emotionally, exquisitely phrased, assertive or tender as the narratives demand—in discrete backdrops with unobtrusive soloing, delicate washes of strings and weeping steel, and strictly sotto voce background support. The most atmospheric setting is saved for the wanderlust narrative of “The Wayward Wind,” with whispering strings cushioning Smith’s anguished reflections and Marty’s B-Bender howls adding a surreal southwestern edge to the soundscape. Connie Smith is country incarnate. –David McGee

‘The Wayward Wind,’ Connie Smith, from Love, Prison and Heartaches, produced by Marty Stuart

***

10. LOVE CALLED HER HOME (EP), Regina Vandereijk (Royal Increase Music)

Sometimes you come across a singer of significant sensitivity and sometimes you come across a skillful songwriter, but rarely do you come across someone who combines both. Regina Vandereijk has both attributes in abundance.

Regina is a worship leader and co-founder of a discipleship school called Royal Increase in Gouda, NL, where she co-leads a collective of artists, with her husband, Willo. Regina was born and raised in the mountains of North Carolina, but currently resides with Willo in Gouda, Netherlands. Regina’s style of sacred music, grounded in the acoustic singer-songwriter tradition, is on full display on her four-track EP Love Called Her Home. To her folk style she adds doses of blues, gospel, and country. The result is a mix of the Christian balladry of Lauren Daigle and the earthiness and commanding conviction of Wynonna Judd.

‘Mighty Waters (Midnight Moon),’ Regina Vandereijk, from Love Called Her Home

The title track is just as strong melodically and even more powerful lyrically as “Oh Jesus (The Glory of the King).” With country crossover appeal, “Love Called Her Home” is her riveting personal testimony of finding salvation after years of indulging in sinful ways. “Mighty Waters (Midnight Moon)” is a metaphorical testimony of the healing waters of baptism. Regina’s opening shouts of “freedom” and the swampy guitar and organ on “Victory” might well be a triumphant Civil Rights song as much as it is her declaration of commitment to her faith.You have to go back to Aretha Franklin’s 1968 hit “Think” to hear a more meaningful and deeply felt cry of “Freedom!”

Although she now lives in the Netherlands, Regina Vandereijk gets her rootsy groove from her North Carolina birthplace. Her first full album is due this month. It could part the waters. Stay tuned. –Reviewed in Deep Roots by Bob. Marovich

Follow this link to the reviews/videos of the Elite Half-Hundred 2024 honorees.