Angéle Dubeau (center) & La Pietà: Noël stands out as a classical holiday album with a difference.

By David McGee

A STAR’S LIGHT DOES FALL

Margaret Slovak & Chris Maresh

Slovak Music (2024)

NOËL

Angéle Dubeau & La Pietà

Analekta (2010)

WINTER SONGS

Ola Gjeilo

Decca Classics (2017)

Though this review takes its headline from the title of a soothing and beautiful beloved Austrian Christmas carol dating back to 1865, it serves in this instance as a summation of the collective feeling evoked by the three albums in question here. The titular artists offer music of serenity, of contemplation, of restoration, of reverence, of intimacy, performed on stringed acoustic instruments, honoring the Christmas season and the event the season celebrates and worships, with the only voices to be heard being those of the acclaimed U.K.-based collegiate Choir of Royal Holloway on composer-pianist Ola Gjeilo’s Winter Songs. Despite its absence from any of these long-players, “Still, Still, Still” does provide a lyric snippet as the most succinct formulation of the magic and majesty found herein. To wit: While angel hosts from heav’n come winging/Sweetest songs of joy are singing.

Though this review takes its headline from the title of a soothing and beautiful beloved Austrian Christmas carol dating back to 1865, it serves in this instance as a summation of the collective feeling evoked by the three albums in question here. The titular artists offer music of serenity, of contemplation, of restoration, of reverence, of intimacy, performed on stringed acoustic instruments, honoring the Christmas season and the event the season celebrates and worships, with the only voices to be heard being those of the acclaimed U.K.-based collegiate Choir of Royal Holloway on composer-pianist Ola Gjeilo’s Winter Songs. Despite its absence from any of these long-players, “Still, Still, Still” does provide a lyric snippet as the most succinct formulation of the magic and majesty found herein. To wit: While angel hosts from heav’n come winging/Sweetest songs of joy are singing.

‘O Come, O Come, Emanuel,’ Margaret Slovak and Chris Maresh, from A Star’s Light Does Fall

The songs comprising one of 2024’s finest Christmas releases, A Star’s Light Does Fall, feature sensitive dialogues between Margaret Slovak’s nylon string guitar and Chris Maresh’s acoustic bass. Fun fact about this duo: Austin residents both, Ms. Slovak and Mr. Maresh began collaborating little more than a year ago and recorded this album only six months later. In addition to residing in the same town, the two musicians both count Czech musicians as fathers and having grown up in households they were as likely to hear classical music as much as polkas. Nominally jazz musicians, they demonstrate striking improvisational skills throughout, as they demonstrate in opening the album with a tender dialogue on “O Come, O Come Emanuel,” subtly rendering theme and variation passages so subtly as to take a listener deep into their shared reverie. At 4:28 the song slowly fades and re-emerges as “I Wonder as I Wander”—as if the two songs are in fact one, and the listener is floating along while the musicians reimagine the latter with all its wonder intact. Again, the instruments complement each other, with Ms. Slovak fashioning delicate variations on the melody as Mr. Maresh supports with minimalist bass counterpoint. On “What Child is This” the concept expands even farther out, embracing a seamless interpolation of “Greensleeves,” with Ms. Slovak adding some fleeting dissonance to her explorations as the tune fades out. In slightly less than 15 minutes, the duo has fashioned something truly mesmerizing. It only gets better. Vince Guaraldi’s holiday classic from A Charlie Brown Christmas, “Christmas Time is Here,” offers playful ambience fashioned by the guitar-bass conversations, with both instruments improvising on the melody line in a way completely empathetic to Guaraldi’s sweet seasonal serenade.

‘Infant Eyes,’ written by Wayne Shorter, performed by Margaret Slovak and Chris Maresh on A Star’s Light Does Fall

‘Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,’ Margaret Slovak and Chris Maresh, from A Star’s Light Does Fall

It’s not all standards with these musicians. Pleasant surprises surface here and there, one being Wayne Shorter’s lovely “Infant Eyes,” written by Shorter for his infant daughter. Not a Christmas song per se, but Christmas is for children, as Glen Campbell reminded us years ago, and Shorter’s warm melody captures the child’s awe-struck spirit in seeing the world with, truly, new eyes. In the duo’s hands, the Shorter gem fits perfectly into the album’s overarching themes. “It captures the essence of hope and renewal,” Ms. Slovak told Jazz Guitar Today’s Joe Barth, adding: “[It’s] a feeling I wanted to convey during this season.” Among the other selections, a most relevant message emerges in Paul Stookey’s “Christmas Dinner,” a 1963 offering from the Peter, Paul & Mary founder, handled with the sensitivity and inclusivity Stookey’s lyrics (unheard here) describe in welcoming to the table those less fortunate in life. Also on the light but no less sincere side: a beautiful exploration of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” an 1943 evergreen by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane introduced by Judy Garland in the Vincent Minnelli-directed film, Meet Me in St. Louis. There’s a whole story about the lyrics being rewritten to be more optimistic, first by Garland and later by Frank Sinatra, requests the songwriters fulfilled, but this lovely instrumental version need only evoke the song’s sense of reunion and fellowship, as it does in fine fashion, which in turn sets up a moving benediction in the introspective instrumental version of Leonard Cohen’s well-traveled “Hallelujah.” The jazz world has no shortage of exceptional guitar/bass albums to offer, and indeed, Ms. Slovak points to the Pat Metheny-Charlie Haden collaboration on Beyond the Missouri Sky as the inspiration for A Star’s Light Does Fall, citing “their magical interplay, their incredible improvisational explorations, and the lyrical nature of the songs. I also love the way that they use space throughout the album; the music really breathes.” Everything she admires about the Metheny-Haden project is in abundant evidence on her and Mr. Maresh’s work. When they play, something refreshing arises from the familiar; and in the silence underpinning their performances, Margaret Slovak and Chris Maresh create a seasonal moment both transcendent and unforgettable.

‘Some Children See Him,’ Margaret Slovak and Chris Maresh, from A Star’s Light Does Fall

In the abovementioned interview with Jazz Guitar Today, Ms. Slovak attributes her preference for the Godin ACS Koda solid body nylon-string guitar to the physical aftermath of injuries she suffered in a 2003 car accident that required eight surgeries and “years of physical therapy” to correct damage to her right hand, arm, shoulder, and brachial plexus nerves. Consequently, “I can no longer play full-bodied guitars; I have to keep my right arm close to my side when I play.” The Godin, she explains, “allows me to keep my arm in the best possible position to reduce pain and increase the function of the nerves that control my hand.”

Not unlike Margaret Slovak, Canadian violin virtuoso Angéle Dubeau has had her career altered by injury. In fact, this past October she announced the end of her performing career due to a nerve injury in her right index finger. In a statement posted on her website she explained: ’My right hand, specifically my index finger—the master of the bow—has lost its sensitivity and is permanently numb. For 58 years, I have applied pressure and precision to the same spot. The nerve has become worn and severely damaged.”

Not unlike Margaret Slovak, Canadian violin virtuoso Angéle Dubeau has had her career altered by injury. In fact, this past October she announced the end of her performing career due to a nerve injury in her right index finger. In a statement posted on her website she explained: ’My right hand, specifically my index finger—the master of the bow—has lost its sensitivity and is permanently numb. For 58 years, I have applied pressure and precision to the same spot. The nerve has become worn and severely damaged.”

Now 58, Ms. Dubeau began playing the violin at age four; at the age of 15 she earned the first of two Master’s degrees from the Montreal Conservatory of Music, followed by studies at the Juilliard School, followed by studies in Romania with Stefan Gheorghiu from 1981 to 1984. Over the course of 45 years as a performing and recording artist she became her country’s most acclaimed and honored violinist. Honors accorded her include being made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1996, Knight of the National Order of Quebec in 2004, and most recently the 2022 Medal of the National Assembly, Quebec and was inducted into the CBC Radio In Concert Hall of Fame in 2023. Her 48-album catalogue includes both solo projects and, more often than not, recordings made with the all-female string ensemble she founded in 1997, La Pietà. Among the many gems in her discography (which includes well-received tributes to Philip Glass and Ludovico Einaudi), 2010’s Noël stands out as a classical holiday album with a difference.

‘Silent Night,’ Angéle Dubeau and La Pietà, from Noël

Noël is in fact a dynamic, engaging global trek through the Christmas music of cultures and traditions far removed from those of Ms. Dubeau’s time. The unison strings’ lush, long lines and the softly rising and falling measures animating this version of Franz Gruber’s “Silent Night” heighten the solemnity of the night like no others in 3:44 of inestimable beauty. Thus Germany’s contribution to Noël. This Nativity celebration journeys elsewhere to find evocations of the Nativity scene in works by composers representing Finland, Italy, France, Austria, the United Kingdom, Russia, Mexico and Canada. According to Lucie Renaud’s liner notes (printed in French and English), Ms. Dubeau’s aim was to answer the question, Has Christmas turned into mere nostalgia, or can we rediscover the true meaning of the celebration? Well, based on the evidence on this disc, asked and answered, in the affirmative. In addition to Ms. Dubeau, this La Pietà configuration numbers 17 musicians, and their cohesiveness, their breathtaking restraint, and the vivid colors coaxed from their instruments reflect their obvious passion for the depth of the texts at hand.

‘La vierge à la crèche’ (‘The Virgin at the Nativity’),’ Angéle Dubeau and La Pietà, from Noël

‘Huron Carol Interlude,’ by contemporary Canadian composer Kelly-Marie Murphy and based on a 1641 Huron carol. Performed by ngéle Dubeau and La Pietà on Noël

Not for Ms. Dubeau and La Pietà is the obvious path to seasonal bliss. Yes, the strings do coalesce in a moving, hymn-like reading of Franz Gruber’s “Silent Night” in an arrangement that allows for the slightest improvisational digressions to melt right back into the familiar heart tugging melody; but the program challenges with fare written for the season but rarely surfacing on disc or in concert airings by mainstream outlets. There are a few composers whose names will ring a bell with the casual classical fan—Vivaldi, Torelli, Sibelius, Glazunov—along with that of Dave Brubeck and possibly British composer (not the actor) John Ireland. This is not to diminish the works of other composers here, no matter their standing in the Classical pantheon, if at all. For instance, French composer Alexander Pèrilhou (1846-1936), a prolific composer for both orchestra and voice, is represented with his “La vierge à la crèche” (“The Virgin at the Nativity),” set to a text by Alphonse Daudet) in which Ms. Dubeau leads La Pietà into the delicate, expressive territory the composer preferred to sheer virtuosic displays, the better to elevate passion over technique. What can only ever be speculated upon—Mary’s emotional state as she was giving birth to the Christ child—is suggested on the one hand by the sumptuousness of the strings in unison and on the other by the poignance of Ms. Dubeau’s lead violin evoking Mary’s inner ruminations. From Germany, from whence the Christmas tree tradition sprang, comes a riveting presentation of late Baroque composer Johann Melchior Molter’s four-part “Concerto Pastorale,” inspired by the scene of the adoration of the shepherds, here being an occasion when the musicians flex the power of their combined instruments—violins, violas, double bass, cellos, harpsichord and glockenspiels—in creating the most exquisitely plaintive adagio, tender and tentative at once, much as the shepherds approaching the cradle must have felt, on through the graceful closing movement, an a tempo di minuetto passage expressing the shepherds’ joy and awe at the unfolding scene. John Ireland’s well-known carol, “The Holy Boy,” described by Ireland’s biographer Muriel Searle, as “simple to the point of austerity,” serves beautifully as a wistful precursor to the album’s coda, “Huron Carol Interlude” by contemporary Canadian composer Kelly-Marie Murphy. This dramatic piece, four and a half minutes in length, is based on the 1641 Huron carol “Jesus Ahatonhia” (“Jesus is Born”) by Jesuit Jean de Brèbeuf, who adapted the original text to reference the culture of the First Nations people, with Jesus wrapped in rabbit skins and sleeping in a bark lodge, with hunters supplanting the shepherds and the Magi represented as three Indian chiefs. Ms. Murphy’s adaptation wends it ways through a variety of shifting, unsettling moods, even bringing in dissonant passages to suggest danger looming in the world outside the manger. Some may find the imagery scandaleux (and Ms. Dubeau, a major fan of Philip Glass’s music, perhaps feeds such a feeling with Impressionistic Glass-like effects infiltrating her arrangement and solos); others may find, upon reflection, that the programming selections and the performances thereof, interior and probing as they are, might well be the “yes, a thousand times yes!” answer to the question of whether we can rediscover the true meaning of Christmas by elevating reverence and respect above nostalgia.

Born in Norway in 1978, pianist-composer Ola Gjeilo moved to the U.S. in 2001 to study composition at Juilliard, moved back to London to finish his Bachelor’s degree at the Royal College Music, returned to Juilliard to finish his Master’s degree and now lives in Laguna Beach, California. A 2023 interview with the Sheet Music Direct Blog credits Gjeilo with more than 70 works for solo piano and chorus. Improvisation is important to Gjeilo—by his own admission, both his solo piano music and choral music begin with improvisation. “It’s really the basis for everything I do,” he says, also citing Keith Jarrett and film composer Thomas Newman’s film music (“which incorporates a lot of improv”) as major influences along with the broad genre of film music (“I think some of our best composers today are working in film”).

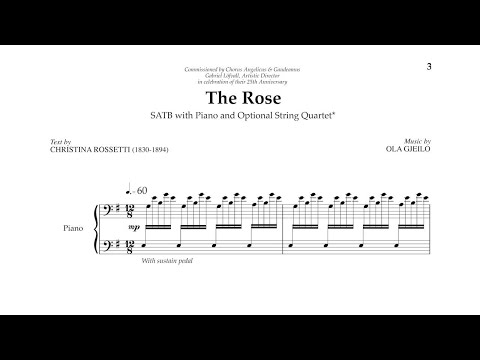

‘The Rose,’ based on a poem by Christina Rosetti. Ola Gjeilo with the Choir of Royal Holloway, 12 Ensemble, conducted by Rupert Gough, performed by Ola Gjeilo on Winter Songs

‘Wintertide,’ a Norwegian folk song, performed by performed by Ola Gjeil owith the Choir of Royal Holloway, 12 Ensemble, conducted by Rupert Gough, on Winter Songs

In addition to being exceedingly captivating in its stark beauty, Gjeilo’s 2017 seasonal album, Winter Songs, goes far in explaining the artist’s growing popularity in the Classical world. That the album embraces and explores two specific seasons at once is recommendation enough but note that the historical sweep of music honoring the true meaning of Christmas further answers the question animating Angéle Dubeau’s Noël. project. In this endeavor, Gjeilo has formidable support: the Choir of Royal Holloway, which dates its origins to 1886, upon the founding of Royal Holloway College in England, features 20 choral scholars and an organ scholar under the direction of Rupert Gough; the Choir in turn is supported by the 12 Ensemble, acclaimed as one of Europe’s leading string orchestras, dedicated to core-classical repertoire along with, as its website notes, “exceptional new commissions and collaborators from a broad range of artistic spheres.” This winning combination has produced a Yuletide album of classic dimensions. There’s nary a misstep on it, and at times it simply seems utterly celestial, as if it has escaped earth’s surly bonds and is communing from the heavens, if not Heaven.

‘The Holly and The Ivy,’ performed by Ola Gjeilo with the Choir of Royal Holloway, 12 Ensemble, conducted by Rupert Gough, on Winter Songs

The album is bookended by two versions of musical settings of Christina Rosetti’s impassioned homage to and cautionary warning about “The Rose,” the “lady of all beauty” that is also a “rose upon a thorn.” The version opening the album features the Choir ascendant over Gjeilo’s ostinato patterns and the 12 Ensemble’s plaintive, soaring solo; the album ending version is an instrumental arrangement featuring violin prominently in front, both urgent and melancholy, its dichotomy betraying Gjeilo’s pronounced affection for film music—the end credits rolling are conspicuous by their absence. Between these two numbers is a set of timeless and time-honored Classical hymns and carols with original instrumental passages featuring Gjeilo and 12 Ensemble with titles revealing their character: “Home,’ “First Snow,” “Dawn” (not the Four Seasons hit!), which is contemplative, introspective, Impressionistic, certainly cinematic and emitting echoes of Vince Guaraldi in Gjeilo’s light, expressive touch across the keys.

‘Silent Night,’ Ola Gjeilo on piano, from Winter Songs

When it’s time to sing, the Royal Holloway Choir turns in masterfully nuanced performances under Gough’s unerring direction. The set list includes a setting of Emily Bronté’s bittersweet “Days of Beauty” (or “When days of beauty deck the vale”); a deeply reverent rendering, with complex harmonies, of Hildegard von Bingen’s “Ave Generoso,” composed in 1555; “Across the Vast Eternal Sky,” an original piece Gjeilo commissioned from poet Charles A. Silvestri that builds and builds in intensity as the Choir, in a deliberate, restrained narrative, rolls out the tale of the phoenix that is, unlike Icarus, not consumed by the sun but reborn by its flames; and the penultimate track, preceding the second iteration of “The Rose,” a tender Norwegian folk song, “Wintertide,” with a gorgeous arrangement of cascading voices and a striking descant. With no disrespect to alluring arrangements of old warhorses “Away in A Manger” and “Silent Night” (a touching solo piano meditation with tender, improvised melodic detours) the standouts among the traditional tunes are clearly “Coventry Carol” and “The Holly and The Ivy,” the latter fueled by slight key and tempo changes to underpin a startling polyphonic cascade bringing a patina of lament to the reading.

“Still, still, still/One can hear the falling snow.” So says the song. Considering the immersive introspective experience these artists generously provide in their seasonal offerings, this bit of 19th Century poetry beckons us in a chaotic time. Listen. Just listen.