Cache la Poudre River, Colorado, from the series Stillwater. Gelatin silver print, 2000. William Wylie, from the exhibition “From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry Lopez,” Sheldon Museum of Art, 2023.

Terry Tempest Williams contemplates her friendship with the late author and what he left behind.

By Terry Tempest William

Barry Lopez once showed me how to drive the back roads of Oregon near Finn Rock at night with no headlights. Why? I asked. “So you can learn to see in the dark like animals do and not be afraid.” He was disarming. Playful. Beyond serious. Demanding. At times, exhausting. Always, illuminating. And like all writers, sometimes self-absorbed. I loved him. He taught me to not only see the world differently, but to feel it more fully. I cannot believe he is gone. Now where do I look?

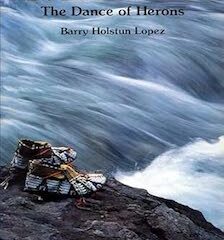

Before he was a writer, he was a photographer. A good one. In fact, the cover image of River Notes, his collection of short fictions based on his own experience of living along the McKenzie River, was taken by him. It is a soft-focus rush of river met by a pair of moccasins placed on a rock facing the water. A credit is given inside the flap of the book: “Western Sioux moccasins courtesy of Lane County Museum, Oregon.” The composition is studied and deliberate, aesthetically pleasing and evocative like each of his stories.

Before he was a writer, he was a photographer. A good one. In fact, the cover image of River Notes, his collection of short fictions based on his own experience of living along the McKenzie River, was taken by him. It is a soft-focus rush of river met by a pair of moccasins placed on a rock facing the water. A credit is given inside the flap of the book: “Western Sioux moccasins courtesy of Lane County Museum, Oregon.” The composition is studied and deliberate, aesthetically pleasing and evocative like each of his stories.

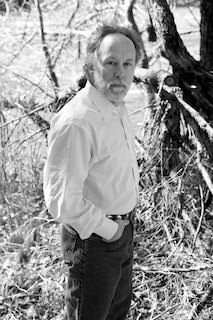

On the back of River Notes is a horizontal strip of four black-and-white photographs of the author, reminiscent of the four flashes of pictures one would spontaneously pose for inside a photo booth with friends. The first shot is Barry looking down, with his index finger resting vertically on his upper lip, the tip of his finger just below his nose; he is deep in thought. The second frame shows him looking upward, his eyes glancing to the right. The third frame is a straightforward gaze, direct. In the last frame, he is looking down, slightly toward the left. Had there been a fifth frame, I imagine Barry’s eyes would have been closed, his head in a slight bow with his two hands pressed together in prayer.

In our long, deep and complicated friendship, I came to rely on his varied moods of mind and heart. I believe part of his genius as a writer was rooted in his access to the extremities between his vulnerability and strength; his knowing and unknowing — call it doubt; and the exquisite arc of revelations created from the depth of his searing intellect to what some critics saw as the naiveté of his beliefs in Nature. In truth, this is where the urgency and wisdom of Barry Lopez dwelled. His hunger to understand the roots of cruelty was located in his wounds. His longing to believe in our species was housed in his faith. When my grandmother died, I gave Barry her silver cross with a small circle of turquoise placed at its center. His own particular devotion to God and the power of our own creativity landed elegantly on each page he wrote, be it his fascination with travel and the intricacies of a ship or plane or an imagined community of resistance on behalf of peace with Earth, where people took care of one another in the midst of darkness. Very little escaped his closely set eyes. You could say, with a smile, that Barry was the Michael Jordan of environmental writing, and when my father gave us his tickets to see the 1987 NBA championship game in Salt Lake City between the Chicago Bulls and the Utah Jazz, Barry never spoke; he was transfixed on Jordan’s every move, with his game stats squarely on his lap. We were rooting for different teams. When the Bulls won, he just looked at me and said, “It wasn’t even a contest with Jordan in the game.” Barry brought this same kind of dramatic intensity to every occasion. His fidelity was to his work where his devotion to language and landscape gave birth to stories — many beautiful stories.

BARRY AND I MET in 1979 in Salt Lake City when he came to read at the University of Utah, paired with Edward Abbey for a special fundraiser for the Utah Wilderness Association. Two thousand people came to hear the rowdy irreverence of “Cactus Ed” court and cajole disruptive behavior. He did not disappoint. People howled like coyotes after Abbey finished reading. When the next speaker took the stage quietly, elegantly, with his head bowed, few had heard of Barry Lopez. But after he read from River Notes, with his deep, sonorous voice, a great and uncommon silence filled the ballroom. No one wanted to leave. A spell had been cast by a Storyteller. We left the reading altered, recognizing that we had not only heard a different voice, one of reverence and grace, but a voice that offered “a forgotten language,” which brought us back into relationship with the sensual world of humans and animals living in concert.

BARRY AND I MET in 1979 in Salt Lake City when he came to read at the University of Utah, paired with Edward Abbey for a special fundraiser for the Utah Wilderness Association. Two thousand people came to hear the rowdy irreverence of “Cactus Ed” court and cajole disruptive behavior. He did not disappoint. People howled like coyotes after Abbey finished reading. When the next speaker took the stage quietly, elegantly, with his head bowed, few had heard of Barry Lopez. But after he read from River Notes, with his deep, sonorous voice, a great and uncommon silence filled the ballroom. No one wanted to leave. A spell had been cast by a Storyteller. We left the reading altered, recognizing that we had not only heard a different voice, one of reverence and grace, but a voice that offered “a forgotten language,” which brought us back into relationship with the sensual world of humans and animals living in concert.

In the story “Drought,” from that collection, Barry Lopez shows us how one sincere act born out of love and a desire to help had the power to bring forth rain in times of drought if someone was “foolish” enough to dance. “I would exhort the river,” his narrator says, and then a few paragraphs on, “With no more strength than there is in a bundle of sticks, I tried to dance, to dance the dance of the long-legged birds who lived in the shallows. I danced it because I could not think of anything more beautiful.” And, with a turn of the page, we learn, “A person cannot be afraid of being foolish. For everything, every gesture is sacred.”

The next day, I drove Barry back to the airport, located near Great Salt Lake. Curious, he asked me questions about the inland sea. I must have gotten lost in my enthusiasm about the lake, how it was our Serengeti of birds — with avocets and stilts, ruddy ducks and terns — how one could float on one’s back and lose all track of time and space and emerge salt-crusted and pickled, and how the lake was a remnant puddle from the ancient Lake Bonneville whose liquid arm reached as far west as Oregon 30,000 years ago. Before Barry boarded the plane, he turned to me and said, “I exhort you to write what you know as a young woman living on the edge of Great Salt Lake.”

There was that word again, exhort. I went home and looked it up in my dictionary: “to strongly encourage or admonish.” It is a biblical word, “a fifteenth-century coinage (that) derives from the Latin verb hortari, meaning ‘to incite,’ and it often implies the ardent urging or admonishing of an orator or preacher.”

Barry Lopez had given me an assignment. I took his assignment seriously.

‘A person cannot be afraid of being foolish. For everything, every gesture is sacred.’ Barry Lopez, Finn Rock, Oregon, 2013. Photo: David Liitschwager, used by permission.

IN 1983, I FIRST VISITED Barry and Sandra, the artist he was married to for 30 years, at their enchanted home in Finn Rock, Oregon. Sandra Barry taught me early on that the color of the river is light. For him, the river was the McKenzie, which fed his life force for 50 years and where salmon spawned each year in the shallows just east of Eugene, Oregon. As an exercise, he would often put on his waders and walk across the river as the mergansers swam around him.

For more than 40 years, I have known that wherever Barry Lopez was in the world — whether he was kneeling on the banks of the McKenzie in prayer awaiting the return of the salmon or watching polar bears standing upright on the edge of the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic or flying his red kite in Antarctica with unbridled joy — the world was being seen by someone who dared to love what could be lost, retrieve what could be found, and know he was listening to those whose voices were being silenced as he was finding an intimacy with, rather than a distance from, the ineffable. In those luminous moments, he would find the exact words to describe what we felt, but didn’t know how to say. He exhorted his readers to pay attention through love.

After a pause in our friendship, we met in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. We held each other close for a long time — and then, for several days, our conversation continued where we had left off. We spoke of home, health, family and shared stories. Always, the stories. And we laughed about all we had learned since we had become older. He had a cane due to a knee injury and he momentarily hung it in a tree. We stood on top of Signal Mountain facing the Teton Range. It began to snow, with large goose-down flakes in full sunlight against a clear blue sky. He looked up and said, “Well, I’ve never seen this before.”

He was of the forest and I was of the desert. Our friendship grew from what was hidden and what was exposed.

Barry Lopez’s very presence incited beauty. Even as his beloved trees in Finn Rock burned to ash in 2020, his eyes were focused on the ground in the name of the work that was now his — “the recovery and restoration of Finn Rock,” the phrase he used in our last correspondence, even as Barry understood what was coming — his own death.

In one of his last essays, “Love in a Time of Terror,” Barry wrote, “In this moment, is it still possible to face the gathering darkness, and say to the physical Earth, and to all its creatures, including ourselves, fiercely and without embarrassment, I love you, and to embrace fearlessly the burning world?”

In one of his last essays, “Love in a Time of Terror,” Barry wrote, “In this moment, is it still possible to face the gathering darkness, and say to the physical Earth, and to all its creatures, including ourselves, fiercely and without embarrassment, I love you, and to embrace fearlessly the burning world?”

Grief is love. Barry’s heartbreak, wisdom, and love in the world remain. At the end of the story “Drought,” the narrator tells us, “Everyone has to learn how to die, that song, that dance, alone and in time. … To stick your hands in the river is to feel the cords that bind the earth together in one piece.”

Peace, my dear Barry. The color of the river is light. You are now light. Hands pressed together in prayer. We bow.

***

This essay is excerpted from Going to See: 30 Writers on Nature, Inspiration, and the World of Barry Lopez, edited by James Perrin Warren and Kurt Caswell, from Mountaineers Books. (It was originally published by ASLE.) All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Terry Tempest Williams is the author of over 20 books, including Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, The Hour of Land, and most recently Erosion: Essays of Undoing. She is writer-in-residence at the Harvard Divinity School and divides her time between Castle Valley, Utah, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Republished by permission of Deep Roots Media Partner High Country News (hcn.org), where it appeared on April 1, 2024.