Seven Voices (+1) on ‘Seven Stanzas’

In the April 2011 issue of our predecessor, www.TheBluegrassSpecial.com, we began pondering the meaning and weight of John Updike’s poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter” via the perspectives of various theologians, ministers, religious philosophers, pundits and seminary students. A year later, in our April 2012 issue, properly headlined the feature “Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas,” and now here we are in 2024 with our 13th installment. This year’s edition offers a couple of new voices joining other of our “greatest hits.” One is John Updike himself (the “+1” of the headline), via the text of a talk he gave on faith and fiction upon being awarded the 1997 Campion Award, given by the Jesuit publication America to a prestigious Christian person of letters. No, it’s not about “Seven Stanzas” per se, but it does offer a window into the role of faith in a major writer whose faith informed his every work. Another is that of Gretchen E. Ziegenhals, Managing Director of Leadership Education at Duke Divinity writing in Faith & Leadership, the online magazine of Duke Divinity School, in 2021 in the wake of “a year of suffering” that “reminds us of Christ’s embodiment and of our own.” Reflecting on the intersection between the assertions, conditional and otherwise, made in “Seven Stanzas” and how those summon us to “embodied work” that benefits humanity in crisis, Ms. Ziegenhals cites three inspiring examples of selfless work being done in “embodied ministries.” Yet another new voice, James Laurence, Pastor of First Lutheran Church of Albemarle (NC), offers a brief, to the point reflection, “The Resurrection is No Metaphor.” Add to these new viewpoints those of some golden oldies culled from previous years’ voices weighing in and vividly illustrating in words the passions evoked and inflamed by Updike’s provocative reflection on Christianity’s defining event, including a respectful dissent by the Rev. Bruce Bode of Quimper Unitarian Universalist Fellowship, who believes Updike “seems to want us to walk through the door into scientific absurdity and irrationality.” Food for thought, indeed.

This year we’ve added additional context, if you will, in the form of four YouTube clips of gospel artists performing songs related to Easter and the Resurrection. We welcome to our flock Albertina Walker and James Cleveland, the ministry of Richard Smallwood, the impressive young Mass choir Youthful Praise, and the gospel giant Shirley Caesar accompanied by Patti Labelle and Gladys Knight on a rousing, uplifting version of “I Knew It Was the Blood.” This, in addition to a regular component of our “Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas” feature in the only musical setting of “Seven Stanzas at Easter” we’ve encountered, by Gregg Smith, Saint Peter’s Choir and Thomas Schmidt from the album Music for an Urban Church, released 2014 on Albany Records. Happy Easter!

***

Seven Stanzas at Easter

By John Updike

(from Telephone Poles and Other Poems, 1963)

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft Spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That-pierced-died, withered, paused, and then

Regathered out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-maché,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

Opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

Embarrassed by the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

***

‘Seven Stanzas’: The Origin Story

By Kathleen Kastilahn

April 2001

Norman D. Kretzmann remembers John Updike as a young Harvard graduate who sought out Clifton Lutheran Church in Marblehead, Mass., because it “nurtured the roots of faith he had grown up with in Pennsylvania.” Kretzmann, pastor of Marblehead at the time, proudly recalls that Updike was among the 96 adults who entered the congregation’s Religious Arts Festival in 1960–and that his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” won $100 for “Best of Show.”

“People in the parishes I served became quite accustomed to my quoting his poem in my Easter sermons at least every few years,” says Kretzmann, who lives in a Minneapolis retirement center and regularly contributes to the Metro Lutheran newspaper.

Kretzmann closely follows Updike’s work, which includes more than 50 novels and books of poems. In a Metro Lutheran review of John Updike and Religion (Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000) he wrote: “I was John Updike’s pastor during the time which the writer later described as his ‘angst-besmogged period.’ Who was the rabbi and who was the disciple of our years together is hard to say.”

The pastor still has Updike’s 41-year-old typed copy of “Seven Stanzas”–“marked up with all sorts of irrelevant notes by me, instructions to me for homiletical purposes or for various secretaries,” he said. And Kretzmann has one more fond memory from the festival: Updike gave the $100 prize back to the congregation.

Originally published at The Lutheran.org (now defunct)

***

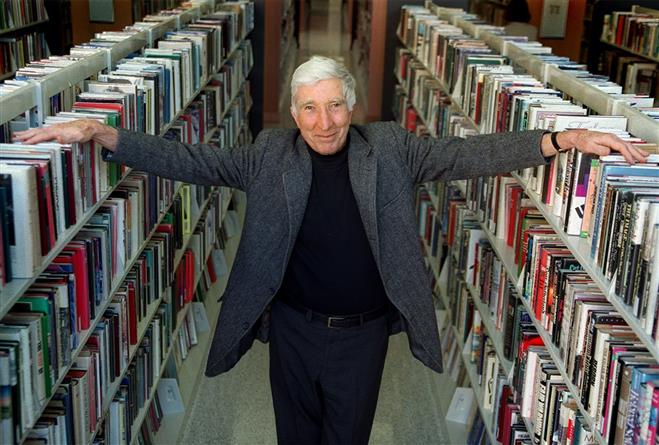

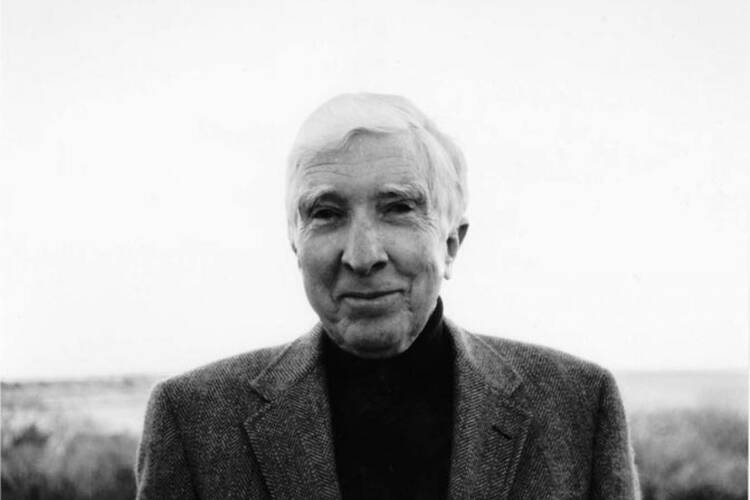

Updike in 2008: ‘… the Christian faith has given me comfort in my life and, I would like to think, courage in my work.’ (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

A Disconcerting Thing

John Updike

October 04, 1997

In 1997 the editors of America (“The Jesuit Review”) awarded John Updike the Campion Award, given to a distinguished Christian person of letters. Upon receiving the prize, Updike gave a talk at America on faith and fiction that later appeared in the magazine under the title “A Disconcerting Thing.” It is reprinted here with permission.

It is a thought-provoking, even disconcerting thing to be given an award as a “distinguished Christian person of letters,” especially an award named for St. Edmund Campion. This brilliant Jesuit, a convert to Catholicism, was, history records, placed on the rack three times in an effort to make him recant his faith. But, though tortured in body, he continued to debate brilliantly with Protestant theologians and won converts among them. He eloquently refuted the prosecutions trumped-up charges of sedition, but was nevertheless hanged, drawn and quartered at the age of 41 in 1581.

How much of such persecution and agony, a recipient of the Campion Award cannot but wonder, would he endure for the sake of his religious convictions? It is all too easy a thing to be a Christian in America, where God’s name is on our coinage, pious pronouncements are routinely expected from elected officials, and churchgoing, though far from unanimous, enjoys a popularity astounding to Europeans. As good Americans we are taught to tolerate our neighbors’ convictions, however bizarre they secretly strike us, and we extend, it may be, something of this easy toleration to ourselves and our own views.

In my own case, I came of intellectual age at a time, the 1950s, when a mild religious revival accompanied our reviving prosperity, and the powerful rational arguments against the Christian tenets were counterbalanced by an intellectual fashion that, a generation after Chesterton and Belloc, saw the Middle Ages still in favor, as a kind of golden era of cultural unity and alleviated anxiety. Among revered literary figures, a considerable number were professing Christians-T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden, Flannery O’Connor and Marianne Moore, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene, Rose Macaulay and Muriel Spark.

The first recipient of the Campion Award, Jacques Maritain in 1955, was the leading but far from the only figure in a movement to give Thomism a vital modern face; at another pole, philosophical existentialism looked to the Danish Lutheran Soren Kierkegaard as a founder, and the stark but expressive crisis-theology of the Calvinist Karl Barth boldly sounded its trumpet against the defensive attenuations of liberal theology. Which is simply to say that when I showed a personal predilection not to let go entirely of the Lutheran faith in which I had been raised, there was no lack of companionship and support in the literary and philosophical currents of the time.

Had I been a young man in an atheist Communist state, or a literary man in the days when Menckenesque mockery was the dominant fashion, I am not sure I would be as eligible as I am to receive this award. But in fact yes, I have been a churchgoer in three Protestant denominations–Lutheran, Congregational, Episcopal–and the Christian faith has given me comfort in my life and, I would like to think, courage in my work. For it tells us that truth is holy and truth-telling, a noble and useful profession, that the reality around us is created and worth celebrating, that men and women are radically imperfect and radically valuable.

Though, as St. Paul as well as Luther and Kierkegaard knew, some intellectual inconvenience and strain attends the maintenance of our faith, at the same time we are freed from certain secular illusions and monochromatic tyrannies of hopeful thought. The bad news can be told full out, for it is not the only news. Indeed it is striking how dark, even offhandedly and farcically dark, the human condition appears as pictured in the fiction of Waugh and Spark and Graham Greene and Flannery O’Connor.

While one can be a Christian and a writer, the phrase “Christian writer” feels somewhat reductive, and most writers so called have resisted it. The late Japanese novelist Shusaku Endo, a Roman Catholic and the Campion medalist in 1990, observed of his Western peers: “Mr. Greene does not like to be called a Catholic writer. Neither did Francois Mauriac. Being a Christian is the opposite of being a writer, Mr. Mauriac said. According to him, coming in contact with sin is natural when you probe the depths of the human heart. Describing sin, a writer himself gets dirty. This contradicts his Christian duty.” Endo went on to say that he could consider himself a Christian writer only insofar as he believed that “there is something in the human unconscious that searches for God.”

And, indeed, in describing the human condition, can we, as Christians, assert more than that? Is not Christian fiction, insofar as it exists, a description of the bewilderment and panic, the sense of hollowness and futility, which afflicts those whose search for God is not successful? And are we not all, within the churches and temples or not, more searcher than finder in this regard?

I ask, while gratefully accepting this award, to be absolved from any duty to provide orthodox morals and consolations in my fiction. Fiction holds the mirror up to this world and cannot show more than this world contains. But I do admit that there are different angles at which to hold the mirror, and that the reading I did in my 20s and 30s, to prop up my faith, also gave me ideas and a slant that shaped my stories and, especially, my novels.

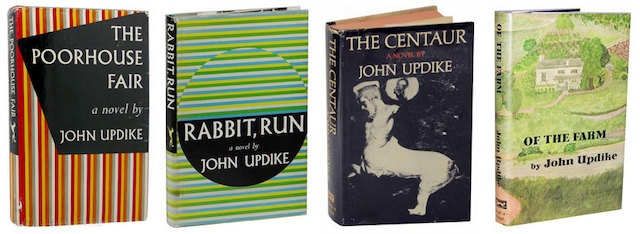

The first, The Poorhouse Fair, carries an epigraph from the Gospel of St. Luke; the next, Rabbit, Run, from Pascal; the third, The Centaur, from Karl Barth; and the fifth, Couples, from Paul Tillich. I thought of my novels as illustrations for texts from Kierkegaard and Barth; the hero of Rabbit, Run was meant to be a representative Kierkegaardian man, as his name, Angstrom, hints. Man in a state of fear and trembling, separated from God, haunted by dread, twisted by the conflicting demands of his animal biology and his human intelligence, of the social contract and the inner imperatives, condemned as if by otherworldly origins to perpetual restlessness–such was, and to some extent remains, my conception.

The modern Christian inherits an intellectual tradition of faulty cosmology and shrewd psychology. St. Augustine was not the first Christian writer nor the last to give us the human soul with its shadows, its Rembrandtesque blacks and whites, its chiaroscuro; this sense of ourselves, as creatures caught in the light, whose decisions and recognitions have a majestic significance, remains to haunt non-Christians as well, and to form, as far as I can see, the raison d’etre of fiction.

***

Seven Voices on Steven Stanzas at Easter, 2023 Edition

1.

Walking Through Closed Doors This Easter

By Gretchen E. Ziegenhals

Managing Director of Leadership Education, Duke Divinity

(March 23, 2021)

I know Easter as a season of hope and renewal. But this Easter, what I most need is an affirmation of the resurrection of the body. After more than a year of global suffering and death, of functioning in virtual spaces, I yearn for a fully embodied Easter.

We are about to mark the first time in the COVID-19 era when we’ve “lapped” a Christian holiday, having completed one full circuit of the liturgical track.

Once again, I won’t physically be in church either for Holy Week or on Easter morning–no sneezing at the lilies, no reveling in the trumpet descants, no hugging friends or admiring children’s shiny Easter shoes.

Like many, I have spent the past year physically isolating from family, friends and colleagues. And I am missing unmasked smiles and handshakes, celebrations, mourning rituals, shared meals.

All that our physical presence means to being community, to being the body of Christ, has been radically altered. Even one-on-one relationships have changed in subtle ways as we keep six feet apart and flap our arms to symbolize cheerful hugs.

‘I Know It Was the Blood,’ Shirley Caesar, with Patti Labelle and Gladys Knight, from the album Shirley Caesar and Friends

This Easter, perhaps like never before, I need to name and reaffirm the embodied nature of our lives and of our resurrection faith. I need the kind of physical resurrection John Updike describes in his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” He writes in the first stanza:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

This Easter–as exhausted doctors, nurses, chaplains and paramedics might agree–we need the assurance that cells and molecules will “reknit,” that amino acids will “rekindle.”

This is an Easter for families who have suffered the untimely loss of loved ones to know that the resurrection hope is a tangible, flesh-and-blood promise of the resurrection of the body.

This is an Easter for us–like Thomas–to put our fingers in the nail holes of Jesus’ palms, so that we can believe.

Updike explains:

It was not as the flowers,

each soft Spring recurrent;

it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

it was as His flesh: ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that — pierced — died, withered, paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.

This is not an Easter to soft-peddle the gospel in our pulpits and everyday workings and words. Updike admonishes:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

We need this Jesus of Luke 24 who, having suddenly, mysteriously appeared in the room where the disciples cower, thinking they’ve seen a spirit, says, “See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me, and see; for a spirit has not flesh and bones as you see that I have.” And then, “Have you anything here to eat?” (Luke 24:39, 41 RSV).

What does it mean for us to celebrate the kind of savior who can unexpectedly materialize–who can walk through closed doors (John 20:19)–yet who wants to eat a meal?

Updike’s “let us walk through the door” this Easter might mean that we embrace and affirm both the miracle and the resurrection of the body to those who look to us for hope and for direction. We and they need it more than ever.

And if we believe in the resurrection of the body, we will respect all bodies here among us–Black, brown and white bodies; rich and poor; male, female, trans and nonbinary; straight and gay; friend and stranger; young and old.

And we will do that by supporting economic policies that make it possible for these bodies to be well fed, provided with equitable health care, and housed in neighborhoods that are safe, vibrant and just.

While we wait for the resurrection–for our bodies and those of our loved ones to be “regathered,” as Updike describes–there is embodied work for us to do now, despite our pandemic limitations: the work of justice and equity; the work of feeding and housing; the work of sharing bread, employment and fellowship; the work of making room for other voices and bodies; the work of ministering to the sick and the lonely in whatever ways we can.

We can look to examples of those working in such embodied Ministries:

The Rev. Dr. Heber Brown III, the pastor of Baltimore’s Pleasant Hope Baptist Church, is helping Black churches and Black farmers create a more secure food system and reconnect with the land. Through the Black Church Food Security Network, which he founded in 2015, Brown is building a community-led system of church gardens and church farmers markets to help Black people grow and access healthy food.

The Rev. Liz Walker, the pastor of Boston’s Roxbury Presbyterian Church, is caring for the body of Christ in multiple ways during this time as well. Leveraging her background in broadcasting, Walker is engaged in faith-based outreach to help neighbors access information and make informed decisions about the COVID-19 vaccines for their bodies.

All Saints Church in Pasadena began sheltering unhoused people on their campus during the pandemic and went on to create the Safe Haven Bridge to Housing ministry, which includes cooperation with social service agencies and health care workers, to make sure their overnight guests have the structures in place to keep them safe and healthy.

These are only a few examples of embodied ministries that honor the resurrected Christ we worship and serve.

Inaugural poet Amanda Gorman writes of the pandemic, in her poem “The Miracle of Morning”:

The question isn’t if we can weather this unknown,

But how we will weather this unknown together.

Gorman continues:

For it’s our grief that gives us our gratitude,

Shows us how to find hope, if we ever lose it.

So ensure that this ache wasn’t endured in vain:

Do not ignore the pain. Give it purpose. Use it.

Alleluia! He is risen indeed!

©Faith & Leadership, the online magazine of Leadership Educatiopn at Duke Divinity, which designs educational services, develops intellectual resources, and facilitates networks of institutions.

***

II.

The Resurrection is No Metaphor

By James Laurence

Pastor, First Lutheran Church of Albemarle (NC)

If Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation is in vain and your faith is in vain … But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died. 1 Corinthians 15: 14, 20

James Laurence

I was pleasantly surprised to learn that “Seven Stanzas at Easter” by John Updike was first written for a Lutheran congregation. But that’s not why I am sharing it here. I am sharing it here because it is, to me, a great re-telling of 1 Corinthians 15, and a timely reminder that our faith is entirely based on the historical fact that Jesus of Nazareth rose from the dead. If “Christ has not been raised” then we are “of all people most to be pitied.” But if he did, then it changes everything. Absolutely everything. And I have staked my life and my hope on this wonderful belief that his resurrection is real, as real as his life and his death. The gospel is true, all of it. Everything depends on this.

What John Updike invites us to do, in this poem, is to double-down on this belief, and remind ourselves that the resurrection is no metaphor–it is a historical fact on which the Church stands. So let us “walk through the door” of this truth and have our lives changed forever.

Posted April 10, 2023 at My Pastoral Ponderings

***

III.

Updike, The Believer

By Dave Schelhaas

April 14, 2020

During the 1950’s, John Updike worshipped at a Lutheran church in Marblehead, MA, a church similar in some respects to the Lutheran church of his youth in Pennsylvania. When the congregation sponsored a Religious Arts Festival and offered a $100 prize for the best artwork, Updike submitted the poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” He won and received the $100 which he promptly gave back to the church and over the years “Seven Stanzas at Easter” has become a much-loved poem.

I was drawn as a reader to the short stories of Updike before I encountered his poetry, and it was the richness of his prose along with the frequent religious content that drew me. My favorite Updike piece to this day is the short story “Pigeon Feathers.” It ends with a boy (a thinly disguised young Updike) burying some pigeons he had shot. You will see in this quotation, the character’s certainty (and Updike’s hope?) that when he dies, God will raise him from the dead:

As he fitted the last two, still pliant, on the top, and stood up, crusty coverings were lifted from him, and with a feminine, slipping sensation along his nerves that seemed to give the air hands, he was robed in this certainty: that the God who had lavished such craft upon these worthless birds would not destroy His whole Creation by refusing to let David live forever.

In response to questions about his faith, Updike has said, “I have been a churchgoer in three Protestant denominations—Lutheran, Congregational, Episcopal—and the Christian faith has given me comfort in my life and, I would like to think, courage in my work. For it tells us that truth is holy, and truth-telling a noble and useful profession; that the reality around us is created and worth celebrating; that men and women are radically imperfect and radically valuable” (Yerkes 4). Serious readers will agree, based on his personal statements as well as his fiction and poetry, that Updike was a believer.

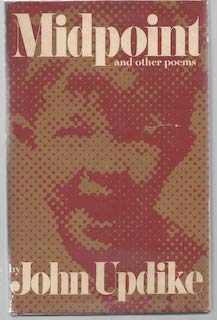

The two great theological heroes of his life were Karl Barth and Soren Kierkegaard. In 1959 while he was going through a spiritual crisis, “he got through it by clinging to the stern neo-orthodoxy of Swiss theologian Karl Barth.” In his autobiographical poem Midpoint, Updike quotes Karl Barth’s assertion that “a drowning man cannot pull himself out by his own hair.” In an interview about the poem he said that he believed this meant “here is no help from within—without the supernatural, the natural is a pit of horror. I believe that all problems are basically insoluble and faith is a leap out of despair” (Hunt 17).

The two great theological heroes of his life were Karl Barth and Soren Kierkegaard. In 1959 while he was going through a spiritual crisis, “he got through it by clinging to the stern neo-orthodoxy of Swiss theologian Karl Barth.” In his autobiographical poem Midpoint, Updike quotes Karl Barth’s assertion that “a drowning man cannot pull himself out by his own hair.” In an interview about the poem he said that he believed this meant “here is no help from within—without the supernatural, the natural is a pit of horror. I believe that all problems are basically insoluble and faith is a leap out of despair” (Hunt 17).

Updike writes that he fell in love with Kierkegaard, the Danish Christian existentialist, in his early twenties. He read the naturalistic existentialists at that time also, but they “didn’t seem to solve any problems the way Kierkegaard’s approach did” (Hunt 12).

Now, understanding more about Updike, what do we need to unpack in this poem? Let’s start with the title.

Why seven stanzas? Perhaps it’s simply how many stanzas it took to say what he wanted to say, but it’s more likely that knowing seven represents completeness, he uses that number in his title to suggest the completion of Christ’s work in his resurrection.

‘Seven Stanzas at Easter,’ a musical interpretation by Gregg Smith, Saint Peter’s Choir and Thomas Schmidt, from Music for an Urban Church, released 2014 on Albany Records

And why that irksome if in line one? Is Updike revealing his doubt that the resurrection occurred? I don’t think so. More likely he recognizes he is writing in a secular age where many clerics and church members are explaining away the supernatural elements of their Christianity and therefore also the very possibility of resurrection. All of stanza four is devoted to chastising the liberal church for its attempt to reduce the resurrection to something explainable, something natural.

Updike’s task in this poem is to convince readers in our scientific age that, unnatural though it be, resurrection has happened. A dominant feature of the poem is its use of scientific language as a way of establishing what happened when Christ arose and what will happen when we are resurrected: “molecules will reknit,” “amino acids rekindle.” Just as he had before he died, the resurrected Christ will have a “hinged thumb,” “valved heart,” and so forth. If this is not the case, the “church will fall.”

I have always been puzzled by that angel in stanza six “weighty with Max Planck quanta.” What in the world does this mean? My friend, physicist John Zwart, says, “the idea of light quanta (or photons as they came to be called) fundamentally changed our understanding of the creation . . . Planck’s ad hoc assumption that the energy of light was not a continuously variable quantity, but instead came in integer multiples of hf. . . became one of the fundamentals that physicists and other science folk use to understand the creation.”

Zwart concludes, “I expect that Updike is expanding on his ‘make it a real angel’ by stating that the angelic light is real light as we currently understand it.” (I thank you, John, for helping me to understand this puzzling line.)

Updike ends stanza four with “Let us walk through the door,” thus urging us to enter into the world of faith, the world of those who believe in the resurrection. Stanza five, beginning with “The stone is rolled back. . .” reveals the open door of stanza four.

At the same time, the stone continues the theme of realism. After insisting that it is a real stone, Updike asks that it also be seen as the vast rock of materiality that “will eclipse for each of us/the wide light of day.’’ In other words, all of us are going to die and this death as well as a gravestone or some other material substance is going to eclipse for us “the wide light of day.” But, in the day of resurrection we shall walk through the door that Christ opened into eternal life.

In the last stanza we find two words with the same Latin root, monstrum: “monstrous” and “remonstrance.” Here, it seems to me that Updike, like the metaphysical poets of old is making a complex pun. The first meaning of “monstrous” is “large, huge, enormous.” The common meaning of “monstrance” is (from the Roman Catholic Church) “a receptacle in which the consecrated Host is exposed for adoration.” Taking these words as they are used in the last stanza, we might paraphrase them by saying, “Let us not diminish the enormity of the Biblical account of the resurrection, for if we do we might in the day of resurrection be deeply shamed, by the reappearance of the living host, Jesus Christ. If we have doubted the reality of the resurrection, we might be filled with remonstrance, that is, shame and regret, when we see the little communion wafer next to the life-sized Christ (the monstrance eclipsed by Re-monstrance).

“Seven Stanzas at Easter” is not an especially lyrical poem, though Updike is capable of marvelous lyricism. Rather, it is down-to-earth in its tone and language (except for one marvelous pun). Updike does not intend to charm us with flights of eloquence, great swaths of words that roll over us like ocean waves. Nope. His language here is scientific, prosaic, as down to earth as hinged toes.

Works Cited

Hunt, George W., S. J. John Updike and the Three Great Secret Things: Sex, Religion, and Art. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1980.

Yerkes, James. John Updike and Religion. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999.

About the Author

About the Author

David Schelhaas taught high school English for 23 years and English at Dordt College in Sioux Center for 20 years. He is retired and lives in Sioux Center with his wife, Jeri. Dave Schelhaas is Professor Emeritus of English at Dordt.

Copyright 2020, In All Things, a publication of the Andreas Center at Dordt University

***

IV.

Steadfast and Immovable

John M. Buchanan

Pastor, Fourth Presbyterian Church

(Excerpt from a longer sermon delivered on Easter Sunday, April 12, 2009 and published at the Fourth Presbyterian Church website, www.fourthchurch.org)

John Updike wrote a wonderful poem in 1961 for, I am happy to say, the Christian Century: “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” Updike was a very distinguished author, essayist, literary critic, and poet. He was also a believer, a church member, a Sunday School teacher. He died on January 27, and those of us who were regularly enriched by his writing greatly miss him. ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter” will find its way into a lot of Easter sermons this year I suspect:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

Updike has walked through that door. Remarkably, in his last months of life he wrote a group of wonderful poems, which were published in the New Yorker after he died. When he realized he might be seriously sick, he wrote,

How not to think of death? I see clear through to the ultimate page . . . Be with me, words, a little longer.

He wrote the last poem December 22; he thinks about Sunday School and Christmas pageants, the ordinary mystery of ordinary people believing and trusting, and concludes, in the last lines he ever wrote, remembering the words of the beloved Twenty-Third Psalm:

Surely—magnificent, that “surely”—goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, my life forever.

That’s it finally. Because Jesus Christ is risen, because of Easter, we know surely that mercy shall follow all the days of our lives and the lives of our dear ones and beyond, forever.

‘He Lives,’ Youthful Praise

The Gospel says simply that when that astonishing day was over, Peter and John returned to their homes. So may we return to our homes, our lives in the world, steadfast and immovable, with resolve to follow him all the days of our lives, with laughter and great joy in our hearts.

For Christ our Lord is risen. He is risen indeed.

Amen.

Sermon © Fourth Presbyterian Church

***

V.

The Empty Tomb (Mikhail Nesterov, 1889. Mikhail Nesterov’s career spanned the pre-Revolutionary era, when he studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, through the Communist era. He began painting religious themes as a young man in the 1890s.)

‘What Door Now Stands Open?”

excerpt from Easter Day Sermon 2004

by the Bishop of Meath and Kildare,

the Most Revd Dr. Richard Clarke

at St. Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare, Easter Day, 11 April 2004

Revelation 3.8 “I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

Most Revd. Richard Clark

The Gospels are of course certainly talking about the Resurrection as a real event, an event in human history. There is, as we know, a condescending and superior approach to the whole matter which suggests that the Gospel writers were speaking of a symbolic resurrection, that Jesus remained very much dead, and that what we call Easter was merely a realization on the part of the disciples that this man Jesus Christ was possibly on the right lines after all. His resurrection was in their heads and in their imagination, but nowhere else. This is, it seems to me, staggeringly patronizing–patronizing about the Gospel writers who would have known perfectly well how to make it clear if they were writing metaphor, patronizing about generation upon generation of great Christian thinkers and writers who were in fact not gullible idiots, patronizing about us who don’t like to think of ourselves either as fools or as fantasists. It’s actually patronizing about God as well. As the American writer and poet John Updike puts it so neatly, in one of his “Seven Stanzas at Easter,”

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages;

let us walk through the door.

The question accordingly becomes a matter, not only of the objective reality of Resurrection, but also of the impact on the lives of disciples. disciples of the twenty-first century as of the first century–of how disciples walk through this door of which both the writer of the Book of Revelation and John Updike speak to us. The question becomes, “What effect does the resurrection of Jesus Christ have on our lives?” “What door now stands open?”

*The Resurrection means first that, as individuals, we must look at Christ in a different way. Mary Magdalene, who had loved and admired him before, now finds herself utterly transformed by him. She becomes different, because everything falls into place. All that he had said and had done were no longer the words and actions of a good man, even the best man there had ever been, it had all been given an eternal reality for her which could not be contradicted or ever destroyed. No matter how often we are told that it will not do to patronize Christ, and to treat him as an amiable carpenter with a good line in stories (who would however not have survived for very long in any real grown-up world), we still do it. The resurrection is the playing of the trump card which tells us that if we not treat him with the utmost seriousness and with total reverence, it is we who are the buffoons.

‘Calvary,’ Richard Smallwood

*It means also that we cannot look at others in the same way. Most of the resurrection stories are stories of Christ’s friends meeting together–in a room, in a boat, on a beach, walking to a village. The Easter event is about sharing faith, being part of a community which celebrates the presence of Jesus Christ. We are pushed again and again in the Easter stories to realize that Christ is real and present with us in the Eucharist, the meal of the Church, as he shares food in a village room, as he asks for food on a shore, as he eats with his disciples in a room in Jerusalem. The risen Christ joins with his followers as they meet together. This is why it is so immensely foolish to imagine that we are somehow doing God a favor when we turn up in church for a service. Worship should never be seen as anything other than an immense privilege to be treated with the greatest humility and reverence, as the God who created us, who keeps us in being and who has smashed through the dreadfulness of death ahead of us, is ready to join us as companion and friend. Christian worship, Christian community and Christian fellowship become Easter gifts to be prized and revered, and for which we should be ever and profoundly thankful to God.

*It means that we can face ourselves in a new way. What are we as individuals without the resurrection? A moderately sophisticated organism which, simply because it has a thing called a “mind,” gets ideas far above its station, but which nevertheless ceases to exist after a few brief spins of a grubby little planet around the nearest, rather insignificant star. It is God in Christ, God in the risen Christ, who gives us a real dignity and a true purpose. This is not the bogus dignity we so readily give ourselves. This is the dignity of being a child of God, given a function and given a purpose to bring others into loving fellowship with him. I have no doubts that the value of our earthly life will be measured in the context of eternity, neither by how much we accumulated for ourselves, nor by how much others feared us or envied us, but by how much more Christian this world became, because we lived in it. And this conviction, if you think about it, only makes any sense in the light of Easter.

Easter is of course far, far more than a good reason for being a Christian. This is why we must never trivialize it or reduce it to a happy ending or a pious parable. It is an open door to faith, to hope, to love, and thus to the fullness of eternal life.

“I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

Published at Diocesan News-Church of Ireland

The Resurrection, Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), circa 1715

***

VI.

‘This Is Poetry in Action’

By Judge Bill Swann

I wrote some lines earlier in Five Proofs of Christianity (WestBow, 2016):

I know as a Christian that Easter is our bedrock. Thirty-three years after the birth of Christ the resurrection occurred, without which, as Paul says, we are nowhere. Our hope is in vain. And we are of all people most to be pitied because we have believed in vain, Easter is for me a coldly rational, magnificent moment.

Perhaps I was wrong. Easter need not be a coldly rational moment, at least not from John Updike’s perspective. Its s a monstrous, shocking moment, literally true in its screaming scientific detail; impossible but true. It is not to be toned down, rationalized, prettified. It is to be confronted and accepted or confronted and fled. There is no compromise:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

Christ rose from the grave, Updike says, with the same hinged thumbs and toes we ourselves have, the same valved heart we have—but with Christ it was a heart that had been pierced, a heart that had died, that withered, and then regathered new strength.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable

No, says Updike, it is Christ himself, body reconstituted, raised from the dead who emerges when the stone is rolled back. A real stone, the same stone which for each of us will someday eclipse our own wide light of day, just as it did for Christ.

John Updike (1932-2009) wrote this 35-line poem in 1960 while attending a Lutheran congregation in Marblehead, Massachusetts. He entered it in the church’s poetry competition, won its hundred-dollar prize, and gave the money back to the congregation.

![Updike at Easter, 2024 Edition 16 Dailey & Vincent - By the Mark (Live] ft. Bill & Gloria Gaither](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Dw-uklIlQE0/hqdefault.jpg)

‘Visceral clarity’: Dailey and Vincent, ‘By the Mark,’ written by David Rawlings and Gillian Welch

He was twenty-eight years old and already wise enough to see, as many gospel singers do, the view from inside the cave, the end of our daylight, approaching death, “the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of time will eclipse for each of us the wide light of day.”

This is visceral clarity Jamie Dailey and Darrin Vincent deal out in “By the Mark,” a new gospel song.

More than fifty years have passed since Updike wrote his poem, and still it drives our thoughts. It makes us decide. This is poetry in action. Christ is for real, or he isn’t. We must decide.

—Excerpt from Politics, Faith, Love: A Judge’s Notes on Things That Matter by Judge Bill Swann (Balboa Press, 2017)

***

VII.

‘A Sermon Without Reason’

By Rev. Bruce Bode

(excerpt from a longer sermon delivered on October 26, 2014 at Quimper Unitarian Universalist Fellowship and posted online in full here.)

For years I’ve been carrying around with me a poem from the modern novelist John Updike, the novelist most well-known for his Rabbit series of novels; he died in 2009. And the poem I carry with me has to do with this notion of breaking the hold of the rational mind through believing something that is unbelievable.

I’ve never quite known what to do with this poem, but now I think I’ve found the spot for it. It’s titled, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” and has to do with believing in a literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus.

Is John Updike, this modern, scientific person, really behind this?

Does he really believe in a literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus?

Perhaps so, as there are many modern, scientifically minded people, who compartmentalize religion, who, for whatever reasons, have areas that are, let us say, “unreconstructed” by modern thought. And, perhaps, this is the case with John Updike.

But mainly I see this poem as Updike protesting against religion that thinks that it can explain everything, that is too rational in its orientation, too much of the head and not enough of the heart, soul, and body.

And this would be a charge that Updike would level against liberal religion, which has emphasized the use and value and importance of reason and thought and science in relation to religion.

But here I believe that Updike, who I appreciate in many respects, is taking us down a wrong path, pitting religion against science and modern cosmology. In protesting against what he regards as the dry rationality of liberal religion, he has dismissed science–and that is not good either for science or religion.

My own main mentor in the ministry, Dr. Duncan Littlefair, after a lifetime of reflecting on the relation of science and religion, came up with a two-part formula that goes like this:

“Part I: To the extent that religion dismisses science, it is invalid.

Part II: To the extent that religion depends on science, it is invalid.”

In Updike’s poem, it would seem that he is dismissing science and modern thought. He calls upon us to “walk through the door,” but I think he’s got the wrong door. He seems to want us to walk through the door into scientific absurdity and irrationality.

‘Wounded for Me,’ Albertina Walker with James Cleveland

So I want to suggest another option, not the door into scientific absurdity and irrationality, but the door into non-rationality and mystery, the kind of mystery that a scientist like Albert Einstein was seized by and spoke of in words such as these:

“The most beautiful and deepest experience a person can have is the sense of the mysterious. It is the underlying principle of religion as well as all serious endeavors in art and science. Anyone who never had this experience seems to me, if not dead, then at least blind. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is a something that our mind cannot grasp and whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly and as a feeble reflection, this is religiousness. In this sense I am religious. To me it suffices to wonder at these secrets and to attempt humbly to grasp with my mind a mere image of the lofty structure of all that there is.”

In this regard, theologian Paul Tillich speaks of two different kinds of “mystery.”

The first kind is the mystery of a puzzle: something not yet known but which could be known; something not yet solved but which could be solved. It’s the kind of mystery that you get in a “mystery novel.” You read the mystery novel to unravel the mystery. The unsolved puzzle carries you until the end when, finally, the mystery is solved; and once solved, the mystery is dissolved–no more mystery.

But there’s a second kind of mystery that is never solved, and this is the kind of mystery that Einstein is talking about. It’s the mystery of being itself, what the Buddhists call the “suchness” of things.

This is the mystery that of its nature cannot be solved. Indeed, one’s sense of mystery–and one’s awe and wonder in the face of the mystery–only deepens as you learn more about its reality. The more you understand, the less you understand. The deeper you probe, the larger grows your sense of wonder. The keener your mind, the greater your humility.

And this is the mystery that religion is–-or ought–-to be, first of all, about.

The Ascension of Christ, Rembrandt (1636)