How it Became the Quintessential Processional Hymn

Once in royal David’s city

stood a lowly cattle shed,

where a mother laid her baby

in a cradle for his bed.

Mary, loving mother mild,

Jesus Christ, her little child.

One of the Christmas traditions celebrated by many persons in the English-speaking world is to tune in on Christmas Eve, either on radio or television, to the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols, originating from King’s College, Cambridge. This tradition began in 1918, was first broadcast in 1928, and is now heard by millions around the world.

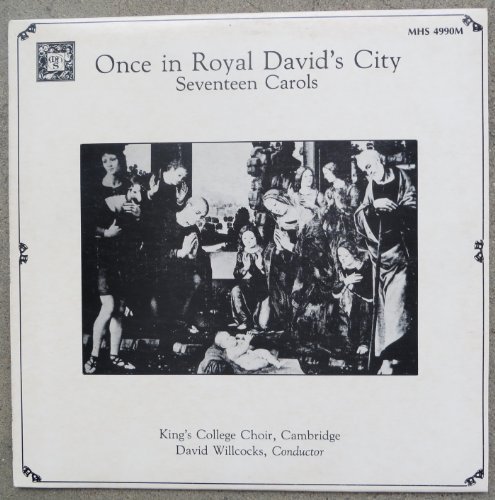

In 1919, Arthur Henry Mann, organist at King’s College (1876-1929), introduced an arrangement of “Once in Royal David’s City” as the processional hymn for the service. In his version, the first stanza is sung unaccompanied by a boy chorister. The choir and then the congregation join in with the organ on succeeding stanzas. This has been the tradition ever since. It is a great honor to be the boy chosen to sing the opening solo-a voice heard literally around the world.

The author of this text, Cecil Frances Alexander (1818-1895), was born in Dublin, Ireland, and began writing in verse from an early age. She became so adept that by the age of 22, several of her hymn texts made it into the hymnbook of the Church of Ireland. Alexander [née Humphreys] married William Alexander, both a clergyman and a poet in his own right who later became the bishop of the Church of Ireland in Derry and later archbishop. Aside from her prolific hymn writing, Mrs. Alexander gave much of her life to charitable work and social causes, something rather rare for women of her day.

‘Once in Royal David’s City,’ The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, from the BBC production of Carols from King’s 2016

“Once in Royal David’s City” first appeared in her collection, Hymns for Little Children (1848), in six stanzas. This particular text was included with others as a means to musically and poetically teach the catechism. It is based on the words of the Apostles’ Creed, “Born of the Virgin Mary,” and is in six stanzas of six lines each. Even though this text is included in the Christmas liturgical sections of most hymnals, the narrative painted by Alexander truly relates to the entire “youth” of Christ and not just his birth.

The first time the text appeared with its most popular tune pairing, IRBY, composed by Henry John Gauntlett (1805-1876), was in the Appendix to the First Edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern (1868). Gauntlett, born in Wellington, Shropshire, England, was trained in the fields of law and music, and is said to have composed over 10,000 hymn tunes. IRBY is the primary tune for which he is known in the United States.

This is one of Alexander’s most narrative and vivid texts, shattering perceptions of the picturesque Nativity with the realities of the lowly stable, and the weak and dependent baby. The hymn’s controversial nature comes from the language expressing the cultural patronizing of children during the Victorian era (words such as “little,” “weak” and “helpless” are ones found particularly appalling in a 21st-century context).

‘Once in Royal David’s City,’ The Choir of Trinity College Cambridge recorded in Trinity College Chapel. Conductor: Stephen Layton; Soprano: Molly Noon; Organ: Harrison Cole. Descant and organ part by David Willcocks

In the spirit of the Romantic poetic era, Alexander speculates in stanza three that Jesus was “little, weak, and helpless” when there is no biblical account to support this. To the contrary, the one biblical witness we have of Jesus’ boyhood in Luke 2:41-52 indicates that he strayed from his parents and caused quite a stir in the temple when teachers “who heard him were amazed at his wisdom and his answers.” (Luke 2:47)

One could make a case that Alexander’s third stanza was more concerned with supporting Victorian child-rearing principles-children as submissive and “seen, but not heard”-rather than providing an accurate account of Jesus’ life. On the other hand, the child who is God incarnate surely felt the human and childlike feelings that all children face.

The final stanza moves from actual childhood to a metaphorical family in which we are all children of God. The poet explores the paradox that this “child, so dear and gentle” is actually the “Lord in heaven” who “leads his children on the place where he has gone.”

The original final stanza explores another paradox-the journey from the “lowly stable” to a place “at God’s right hand.” The little child who sings this song then joins the throngs in heaven who will shine “like stars”:

Not in that poor lowly stable,

with the oxen standing round,

we shall see him; but in heaven,

set at God’s right hand on high;

when like stars his children crowned,

all in white shall wait around.

Dr. Hawn is professor of sacred music at Perkins School of Theology, SMU. Ms. Hanna is a candidate for the Master of Sacred Music degree at Perkins.

Published by permission of Discipleship Ministries, 1908 Grand Avenue, Nashville, TN 37212