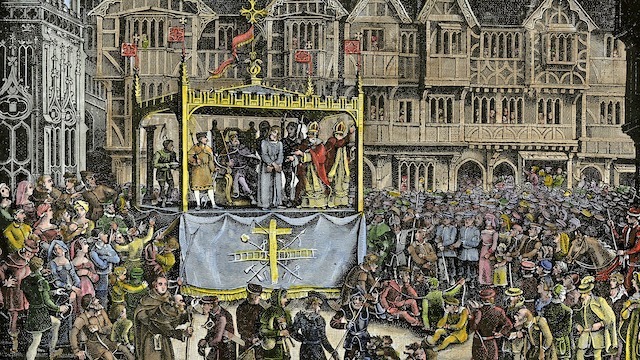

Illustration of a mystery play performance from Thomas Sharp’s ‘Coventry Mysteries’, 1825

“Lully, lullay, thou little tiny child/ Bye bye, lully, lullay…”

Sung from the perspective of women soothing their soon-to-be-slaughtered babies, the “Coventry Carol” is surely the darkest of all Christmas songs. First written down in 1534, this maternal lament was originally part of a medieval mystery play, performed annually in the city from the late 12th century until 1579. Mounted in June, on the Feast of Corpus Christi, The Shearmen and Tailors’ Pageant was a Nativity play retelling events from the Annunciation to the Massacre of the Innocents.

Tableaux and songs were used to bring Bible stories to life in church services as early as the fifth century. But they evolved into popular entertainments that would inspire the Elizabethan dramatists. Pageants performed by guilds of tradesmen drew bawdy, boozy crowds in York, Chester and Lincoln.

In Coventry–where Richard III attended plays shortly before he was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field–the plays lasted for longer than in other cities. There, the boos and hisses would all have been aimed at the original pantomime villain: King Herod.

According to the Gospel of Matthew, the Magi (AKA three wise men) told the Roman client king of Judea that a boy destined to become “king of the Jews” had been born in Bethlehem. To neutralise the threat to his position, Herod ordered the execution of all baby boys under the age of two. An angel warned Joseph to flee to Egypt with Mary and baby Jesus, but parents of other local infants didn’t get the divine tip-off.

‘Coventry Carol,’ the original 1591 version as performed by the Columbine Chorale

Singing from large stages mounted on wheels, three distraught mothers delivered the carol: “Herod the king in his raging/ Set forth upon this day/ By his decree, no life spare thee/ All children young to slay.”

Matthew’s tale of infanticide appears nowhere else in the New Testament. Most historians doubt that it occurred, and suspect the story is a conflation of events including the murder of children in Egypt at Passover. (Herod is also now widely believed to have died four years before Jesus was born.) But the story reflects Herod’s genuinely despotic rule, during which he ordered the execution of three of his own sons as well as one of his 10 wives.

Although the carol’s melody sounds melancholy to modern ears, medieval music lovers are believed to have found its minor key uplifting. The haunting tune makes use of the “Picardy third”— passages written in a minor key resolve on a major chord. It’s an unusual technique, but you can still hear it in pop songs such as The Beatles’ “I’ll Be Back,” The Zombies’ “Time of the Season”and Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy”.

The Protestant monarchy eventually banned the mystery plays because of their Catholic origins. But an original prompt book belonging to an actor/manager called Robert Croo survived long enough to be transcribed by a local antiquarian in the early 19th century. The carol was restored to popularity after the Coventry blitz of November 1940.

Codenamed “Moonlight Sonata,” the 11-hour German raid targeted the city’s munitions factories. More than 550 people were killed and 43,000 homes were destroyed, along with the medieval cathedral. Two charred roof-beams which had fallen in the shape of a cross were bound and placed at the site of the ruined altar.

That Christmas, BBC radio broadcast a service from the ruins during which the provost Dick Howard offered a message of peace. “We are trying,” he said, “hard as it may be, to banish all thoughts of revenge… We are going to try to make a kinder, simpler, a more Christ Child-like sort of world in the days beyond this strife.” The broadcast (part of which is accessible online) ended with the “Coventry Carol.”

‘Coventry Carol/God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,’ medley by Chet Atkins, from his Christmas With Chet Atkins album (1961)

Since then the carol has remained a somber standard, regularly recorded by choral groups. It has also been taken up by an odd spattering of pop artists. In 1961 Tennessee-born country guitarist Chet Atkins brought the moreishness of that Picardy third to the fore. Fourteen years later John Denver assumed a courtly tone as he sang over tinkling ye olde harpsichord and slow-bowed strings. In 1987 Alison Moyet dug deeper into the grief, ululating towards the end of her synth-backed recording. Indie icon Sufjan Stevens tipped the tune into a prettily doomed waltz in 2012.

‘Lullay Lullay (Coventry Carol),’ Annie Lennox, from her A Christmas Cornucopia album

But the most powerful recording was made by Annie Lennox and the African Children’s Choir in 2010. As she sings over raw lute and pounding drums, Lennox’s fury at injustice–both ancient and modern–punches through every spine-tingling syllable.

Republished by permission of Financial Times. Originally published in FT on December 20, 2021.