Holiday Beauty from Doris and Edie

By David McGee

COMPLETE CHRISTMAS COLLECTION

COMPLETE CHRISTMAS COLLECTION

Doris Day

Collectors’ Choice (Released: 2008)

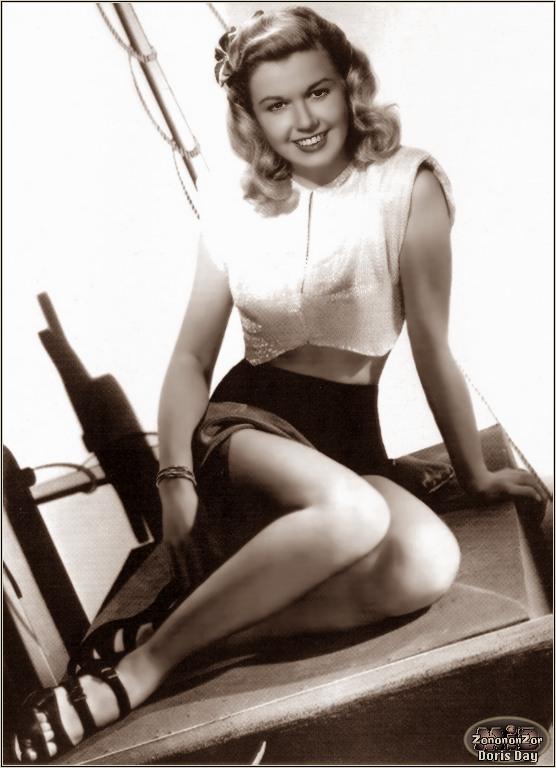

Doris Day occupies rarified rare in show business history. In 2009 she became the all-time female box office champ and sixth among the top 10 box-office stars, irrespective of gender. She was honored with a Golden Globe, a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement in motion pictures, a Legend Award from the Society of Singers and a well-deserved Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. She appeared in 39 films, released 29 albums and logged 460 weeks in the Top 40 charts. Though she started her career as a big band singer (her first hit, “Sentimental Journey,” came in 1945), but after director Michael Curtiz cast her in her first film, 1948’s Romance On the High Seas, she was suddenly a movie star as well. Sometimes immensely gifted artists are undervalued because they go about their work with such ease; Doris Day had that effortless style to go with a wholesome girl-next-door image that, even as the box office receipts piled up, led critics to deride the virginal qualities she projected onscreen. Oscar Levant uttered the most famous dig, saying he knew Doris Day “before she was a virgin.” Annoying, uninformed and unfair, such criticisms ignored the range of roles Ms. Day tackled with flair and the progressive female characters she brought to life on screen well ahead of women’s lib gaining steam.

Doris Day and Rock Hudson in Pillow Talk (1959), featuring Day singing ‘Possess Me.’ Ms. Day’s performance earned her Golden Globe and Academy Award nominations as best actress.

Ms. Day herself addressed the image issue in her 1975 autobiography. Doris Day: Her Own Story, in noting: “The succession of cheerful, period musicals I made, plus Oscar Levant’s highly publicized comment about my virginity (‘I knew Doris Day before she became a virgin.’) contributed to what has been called my ‘image,’ which is a word that baffles me. There never was any intent on my part either in my acting or in my private life to create any such thing as an image.”

Thomas Santopietro, author of the book-length discourse and examination of Ms. Day’s artistry and appeal, Considering Doris Day, in an interview with About.com, says the cultural upheavals of the ‘60s did her no favors: “When the sexual revolution hit in the ’60s, people turned their backs on Doris Day, simplistically deriding her film persona as that of the perennial virgin. It’s a view exemplified by Oscar Levant’s wisecrack ‘I knew Doris Day before she was a virgin.’ That’s a funny line, but it’s all wrong. Doris Day was the only movie star of her time who consistently played independent career women with great jobs, never desperate for a husband, yet people have distorted that fact and as a result have underrated her.”

Doris Day, ‘It All Depends On You,’ from 1955’s Love Me or Leave Me, directed by Charles Vidor and co-starring James Cagney.

At her death on May 13, 1997, the 97-year-old Doris Day was one of only eight recording artists to also have been a four-time top box office earner in the U.S. She lived long enough to see her reputation slowly but surely burnished to its proper bright sheen, with her movies being reconsidered in light of their solid performances and subtle messages of female empowerment. Next, a greater appreciation of her truly formidable musical achievements will be in order. Which would take her back to where she began her journey, back to first aspirations long since fulfilled.

Early on, she was aiming for a career as a dancer, a dream derailed when her legs were severely injured in a car accident in 1937, after which she started taking singing lessons, and at age 17 began performing professionally around her home town of Cincinnati. In 1945, while working with bandleader Les Brown, she had her first hit record, a big one it was, too, in “Sentimental Journey,” now one of the beloved songs in the Great American Songbook. In 1948, though, fed up with the business and having separated from her second husband, Day was ready to go back home to Cincinnati when her agent persuaded her to join him at a party at the home of composer Jule Styne. We now have Styne and his collaborator Sammy Cahn to thank for one of the truly remarkable recording careers in pop history. When she sang “Embraceable You” at the party, Styne and Cahn recommended her for a role in the film they were working on, Romance On the High Seas, which produced another hit for her in “It’s Magic.” The movie roles came regularly and with them great songs–by 1953 she had notched her fourth chart topping hit in the wonderful “Secret Love,” from Calamity Jane. In 1956, her role in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much gave her a signature song in “Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be),” which Day reportedly despised even as it became her theme song and showed up in two other of her movies, 1960’s Please Don’t Eat the Daisies and as a duet with Arthur Godfrey in 1966’s The Glass Bottom Boat. Her last top 10 hit came in 1958, with “Everybody Loves a Lover,” but she continued recording into 1967, with her final LP being The Love Album, which did not see a commercial release until 1994. For the Columbia label she recorded more than 650 songs; all are not gems, of course, but her voice had personality to burn and a sweet charm that would not be denied. She didn’t do melancholy; hers was an incessantly sunny disposition–feel-good music (before the term was coined) that convinced this singer was your friend and confidante, speaking in a friendly, welcoming tone in bringing you into her confidence. In 2011 she surprised everyone by releasing what would be her final album, My Heart, co-produced by her son. Terry Melcher, himself a legendary rock ‘n’ roll producer (Paul Revere and The Raiders, among others). Most of the song selections were actually recorded in the mid-‘80s for a television special, while four tracks were from previously issued albums.

Only one Doris Day Christmas album exists, from 1964, and its title is as straightforward as her singing: The Doris Day Christmas Album. The folks at Collectors’ Choice, however, have included another nine tracks of Christmas fare, most from non-album singles sides, and put it all together on one CD as Complete Christmas Collection. It’s pretty amazing and pretty much beyond criticism—sure, you can hear her strain for a couple of fleeting moments when she tries to belt out a refrain, but she quickly reins it back in and makes a smooth, seamless transition back to the original melody line and to the vocal place where she thrives. The first dozen cuts on the CD are from the album proper, and feature wonderfully low-key, richly textured orchestral arrangements by Frank Comstock and/or Pete King. Her “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” is a breathtaking balance of subdued, thoughtful singing on Day’s part over a sumptuous, perfectly calibrated string-rich arrangement–one of the best versions ever of this holiday chestnut. Her tender “Snowfall,” with its cascades of strings and muted, heralding horns, achieves an ethereal quality on the strength of Day’s impressionistic musings on the fanciful, whimsical nature of snowflakes and the beauty of their appearance–it’s the model for a similarly poetic discourse four years later by Tony Bennett on his classic Snowfall album.

Doris Day, ‘Christmas Story,’ from the 1951 film On Moonlight Bay, directed by Roy Del Ruth, co-starring Gordon MacRae and loosely based on Booth Tarkington’s Penrod stories. In 1953 the entire cast returned for a sequel, By The Light Of the Silvery Moon.

Doris Day, ‘I’ll Be Home for Christmas,’ from Complete Christmas Collection, and featured on the 1964 Doris Day Christmas Album.

Interestingly, the span of years represented by these recordings happens to chronicle the singer’s maturation as a song stylist. On the earliest cut, a 1946 rendition of the Mel Tormé-Robert Wells evergreen “The Christmas Song,” heavier on horns than the usual arrangement of this standard, Day staggers her phrasing, singing behind and even ahead of the beat at points and sharply clipping the lines at the end of stanzas instead of flowing along with the melody before taking a breath to start another verse; contrast this with the version on her 1964 Christmas album: the vocal is smooth and creamy, she’s stretching out certain passages, adding extra syllables and subtly playing with the tempo. The voice is older, of course, and has a weight absent from the chirpy youth of 18 years earlier, but with that also comes a more reflective, knowing subtext–listen to the clipped, upbeat “though it’s been said/many times, many way/merry Christmastoyou,” as opposed to the later version’s graceful, low-key “merry Christmas…to…you,” as comforting as it is heart tugging.

Doris Day, ‘Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow’ from her 1964 Doris Day Christmas Album

Doris Day, ‘The Christmas Song,’ from her 1964 Doris Day Christmas Album. Ms. Day’s first recording of the Mel Tormé-Robert Wells classic came in 1946, when she was singing with Les Brown and His Orchestra. Both recordings are included on Complete Christmas Collection.

Despite her squeaky-clean onscreen image, Day had plenty of turmoil in her personal life (four marriages, for starters), and there was a reason Oscar Levant once said he knew her “before she was a virgin.” But whereas her friend and contemporary Frank Sinatra–who admittedly recorded far more Christmas material far longer into his life than did Day–brought a measure of his own personal pain and regrets to his later seasonal work, Day leaned towards being either swooningly romantic–most tantalizingly in her dreamy, torch rendition of “Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!”–or playful and frisky, as she demonstrates with a gentle but smoldering treatment of “I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm”; you won’t hear Sinatra’s swagger in her version of “The Christmas Waltz,” but you will hear sincere good tidings with a frisson of flirtiness, a little personal twist, a tinge of romantic possibility in her sunny tone. Almost every song has something in it to grab the attention, whether it be the seductive, deliberate approach to “Toyland,” so full of wonder, or the sincere, spiritually resonant reading of a call for fellowship, tolerance and unity in “Let No Walls Divide,” a 1961 cut off a Christmas album featuring an all-star lineup of Columbia recording stars. Wonderful technique is at work in all of Day’s recordings, but what she wrought in her Christmas material is something beyond technique, something abiding in the exalted realm of the heart, where pure feeling produces the peace that passes all understanding. This is beautiful.

‘Listening to these Christmas recordings from the 1950s, it’s clear to me that Edie Adams and Ernie Kovacs were hopelessly and totally in love.’

THE EDIE ADAMS CHRISTMAS ALBUM featuring ERNIE KOVACS (1952)

Omnivore Recordings (Released 2012)

Certainly one of the benefits of the DVD era has been the reissuing of brilliant, nigh on to surreal TV shows Ernie Kovacs presented on various networks in the 1950s. Mustachioed, with an ever-present cigar and impish twinkle in his eye, Kovacs was as unpredictable a live TV presence as the medium has ever seen, with his clever sight gags and verbal agility paving the way for a more sophisticated–and subversive–brand of humor than the mainstream big-name comedians of the ‘50s were offering. Kovacs was more than a decade ahead of his time, but his wife and co-conspirator, Edie Adams, served as a façade of normalcy in the Kovacs troupe but was never a second banana.

Certainly one of the benefits of the DVD era has been the reissuing of brilliant, nigh on to surreal TV shows Ernie Kovacs presented on various networks in the 1950s. Mustachioed, with an ever-present cigar and impish twinkle in his eye, Kovacs was as unpredictable a live TV presence as the medium has ever seen, with his clever sight gags and verbal agility paving the way for a more sophisticated–and subversive–brand of humor than the mainstream big-name comedians of the ‘50s were offering. Kovacs was more than a decade ahead of his time, but his wife and co-conspirator, Edie Adams, served as a façade of normalcy in the Kovacs troupe but was never a second banana.

A Juilliard-trained vocalist, a graduate of the Columbia School of Drama, a student at the Actors Studio and at the Traphagen School of Fashion Design, a “Miss U.S. Television” beauty contestant winner in 1950, Adams–born Edith Elizabeth Enke in Kingston, Pennsylvania–had a number of appealing career options ahead of her when Kovacs’ producer saw her on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts in 1951 and invited her to audition for the Kovacs show. So immersed in classical was she that she knew only three contemporary pop tunes–so she sang those and got the job. Kovacs was smitten instantly upon meeting her, and eventually won her hand, in 1954 (his wooing of her included mariachi bands materializing at odd moments to serenade the girl of his dreams). On a show known variously as Kovacs Unlimited, The Ernie Kovacs Show and The Ernie Kovacs Rehearsal, airing on three different networks (CBS, NBC and DuMont), from late 1952 through April 1955, Edie Adams became something akin to the ballast on a ship Kovacs purposely steered into choppy comedic waters. A beautiful woman with an air of sophistication about her but also great personal warmth of the girl-next-door kind, Adams proved a versatile player on the Kovacs roster: she could do comedic bits on her own, was a perfect foil for her boss’s unpredictable antics; and being a skilled, expressive singer with a nice touch on ballads and a cheery delivery of uptempo songs, she was an isle of serenity amidst the turbulence of Hurricane Kovacs.

His genius has long been recognized and honored for its barrier-breaking qualities in TV’s golden age, but Edie wasn’t just along for the ride. She had real thespian chops: on the Broadway stage she introduced “Ohio” with Rosalind Russell in Betty Comden, Adolph Green, and Leonard Bernstein’s 1953 Wonderful Town, winning a Theatre World Award for her performance; in the 1956 musical based on Al Capp’s Li’l Abner comic strip adapted for the stage by Norman Panama, Melvin Frank, Johnny Mercer and Gene DePaul, she portrayed Daisy Mae opposite Peter Palmer’s Li’l Abner and took home a Tony Award. When Rodgers and Hammerstein produced their first television musical version of Cinderella starring Julie Andrews, Adams was memorably cast as the Fairy Godmother.

Edie Adams, ‘Christmas in Killarney,’ from The Ernie Kovacs Show. This song and dance piece first aired December 19, 1955 on the NBC Television Network.

Edie Adams also did a great service for historians in paying a transcription service to record the show’s audio so she could review her musical performances with an eye towards improving her presentations on future shows. Sourced from acetates made from those rare kinescopes, Adams’s son, Josh Mills (from Edie’s marriage to Marty Mills, a few years after Kovacs’s death in a car accident in 1962), compiled a delightful collection of Yuletide songs his mother sang on the Kovacs show from the early to mid-’50s. Ernie, of course, makes his presence felt, literally, in both comical and straight man fashion: no great shakes as a singer he, Ernie nevertheless contributes a warm harmony vocal to Edie’s on a lovely treatment of “Silver Bells,” accompanied only by a piano that takes on a music box quality at points. But there’s more than meets the ear here when Ernie and Edie sing together, and Josh nails it in his affectionate liner notes: “Listening to these Christmas recordings from the 1950s, it’s clear to me that Edie Adams and Ernie Kovacs were hopelessly and totally in love.”

Edie Adams offers a merry take on Carl Sigman’s ‘It’s a Marshmallow World,’ from The Edie Adams Christmas Album

Most of the songs, though, are simply Edie solo, with only a piano backing her, giving the album the feel of either a rehearsal or a recital in its plain, unadorned offerings, some of them clearly done with no consideration of mic placement—no strings, no brass, no small combos, only an unidentified pianist who impresses with his witty, nimble excursions on Edie’s cheery rendering of “Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!” and the sensitivity of his reverent backing on “I Wonder As I Wander.” But it’s Edie’s show, and hearing her clear, bright voice again—so reminiscent of Doris Day’s–and being reminded of her savvy as a singer—a wonderful sense of phrasing and an acute ear for a song’s dynamics—makes this one of those Christmas albums worthy of being cued up periodically throughout the year. Her take on “The Christmas Song”—with the pianist embroidering it with periodic glissando runs—really heightens the song’s beauty in its unadorned, stripped-down form. On a deeply felt version of “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” there’s nothing casual about her vocal—deeply invested emotionally in the song’s message, she brings the full force of her classical training to bear on the song’s abiding yearning for home, family and friends with rich, full phrasing at points, a wondrously sustained falsetto at others, and throughout a genuine effort to reach the listener with the song’s message. Elsewhere she does a terrific job with a blues-tinged pop treatment of “Blue Christmas” (this would have been a few years before Elvis cut his classic version); skips merrily along in Carl Sigman’s “It’s a Marshmallow World” (despite some Kovacs antics that trip her up momentarily) and in “Winter Wonderland”; adopts her best Irish brogue in romping through “Christmas in Killarney” (something’s going on with Ernie on this one, as about midway through, the sound of birds chirping suddenly appears and we hear Kovacs laugh and announce “No rehearsal!”); and closes with a touching, saloon-style treatment of “What Are You Doing New Year’s Eve.”

Edie Adams, ‘Blue Christmas,’ predating Elvis’s classic treatment. From The Edie Adams Christmas Album (1952)

Not the least of this album’s virtues are the liner notes penned by Josh Mills. These fill in some of the historical details about how the album came to be but are even more valuable for the history he shares of his memories of Christmas with his mother. On the one hand, he describes indulging her fondness for cooking, even though “she wasn’t a good cook” (and describes our great good fortune in not having to eat her microwave lasagna, “made with tofu instead of ricotta cheese”); on the other, he describes spending Christmas Eves in Jack Lemmon’s home with a big spread catered by Chasen’s restaurant and how one of Lemmon’s other guests, Walter Matthau, taught young Josh a “mind reading card trick.”

Edie Adams, ‘What Are You Doing New Year’s Eve,’ from The Edie Adams Christmas Album (1952)

So this most unexpected holiday albums—because who knew?—turned out to be one of the gems of the 2012 crop. Its informality may not be to everyone’s taste, but that same seeming informality also gives it a greater intimacy than some larger-scale Christmas projects have to offer. It does right in reminding us what a gifted all-around artist Edie Adams was (did I mention she was perfect as a manic Sid Caesar’s wife in Stanley Kramer’s great screen comedy, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World?), but especially shines a much-deserved spotlight on her vocal artistry. One of her albums is titled There’s So Much More, and boy if that’s not an understatement. Here, her charming personality, intelligent and respectful approach to the material and uplifting spirit have produced a seasonal outing that sounds like home. What better recommendation for a Christmas album, I ask you?

Reviews of the Edie Adams Christmas Collection (1952) and Doris Day’s Complete Christmas Collection were published and reviewed separately in TheBluegrassSpecial.com. This 2023 Deep Roots update combines, expands and updates the original reviews.