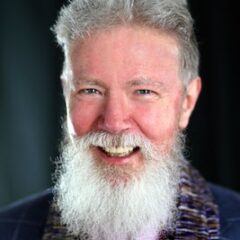

Randall Scotting: a full, rich voice that projects text as an important contributor. (Image: ioulex–Julia Koteliansky & Alexander Kerr)

By Robert Hugill

LOVESICK

LOVESICK

Randall Scotting and Stephen Stubbs

Signum Classics

A program of songs of heartbreak and loss from the American countertenor, exploring a wide range of traditional and 17th-century song in a finely music and expressive performances

I interviewed American countertenor Randall Scotting in October last year, when he released his debut recital disc, The Crown: Heroic Arias for Senesino recorded with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and Lawrence Cummings and released on the Signum Classics label [see my interview]. Having made his Royal Opera House debut in 2019 (in Britten’s Death in Venice), Scotting’s 2022 appearances included the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and his Bavarian State Opera debut, in Georg Friedrich Haas’ Thomas. On 28 May 2023, Scotting will be creating the role of Adone in the world premiere of Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino’s Venere e Adone (Venus and Adonis) at Staatsoper Hamburg, with soprano Layla Claire as Venere, conducted by Kent Nagano.

Randall Scotting’s latest disc, with lutenist Stephen Stubbs on Signum Classics, is called Lovesick and was released, most appropriately, in time for Valentine’s Day this year. It is a program of anti-Valentines, songs of heartbreak and loss from the 17th century featuring music by William Lawes, Étienne Moulinié, Henry Purcell, John Blow, Antonio Cesti, Henry Lawes, John Dowland, Daniele da Castrovillari, and Pierre Guédron, along with a selection of Gaelic, Scottish, Irish and English traditional songs.

‘Black is the Colour off My True Love’s Hair,’ arranged for tenor and lute by John Jacob Niles. Randall Scotting, countertenor, and Stephen Stubbs, lute. From Lovesick.

It is an eclectic mix, ranging widely but the focus is firmly on the 17th century. And the program is arranged thematically, rather than by era or region, so that the recital opens with William Lawes’ “I’m sick of love,” setting a Robert Herrick poem that is a clever play on words, followed by an English version of the traditional Gaelic song, “There’s none to soothe my soul to rest,” and Étienne Moulinié’s “Enfin la beauté que j’adore” (Moulinié was lutenist to Louis XIII’s younger brother). The focus is firmly on the British Isles (with excursions to France, Innsbruck and Venice), with Scotting and Stubbs including traditional songs (usually from collections published in the 18th or early 19th centuries) to highlight the links that the music of Lawes, Purcell and Blow had to these songs. There are songs by both Lawes brothers, and by John Blow, in rather cheeky mode, and the generous selection of Purcell includes music from King Arthur, “O lead me to some peaceful gloom” from Bonduca, and the recital ends with Purcell’s “O solitude.”

This latter gives an indication of the emotional trajectory, we begin with wordplay, then move between a variety of love sicknesses, with John Dowland’s “Time stands still” at the emotional center, before we end with Purcell hymning the joys of solitude, away from the beloved.

‘O, Lead Me to Some Peaceful Gloom,’ written by Henry Purcell. Randall Scotting, countertenor, and Stephen Stubbs, lute. From Lovesick.

There are two 17th-century Italian opera arias. “Luci belli” is from Daniele da Castrovillari’s La Cleopatra, which debuted in Venice in 1662; not much is known about the composer, but the score of his opera survives and Scotting sang the role of Marc’Antonio in the modern premiere of the work in 2015 with Ars Minerva in San Francisco. “Intorno all’idol mio” comes from Cesti’s somewhat better-known L’Orontea; premiered in Innsbruck in 1656, the opera would go on to become one of the most popular in the 17th century.

The idea of the ethereal sound of a countertenor voice in lute songs begins, as far as the modern era is concerned, with Alfred Deller. This sound is now something of a standard trope. Yet John Potter rather provocatively suggests that Dowland, who sang lute songs to his own accompaniment, may well have sounded more like Sting than Deller. Potter and Neil Sorrell’s A History of Singing is a useful corrective for those who believe that singing styles have remained unchanged over the centuries and it is indeed worth taking a listen to Sting’s Songs from the Labyrinth album, which presents another way of performing the lute song (if you can get over the singer’s poor breath control). And, of course, many authorities suggest that the countertenor voice in the early 17th century was closer to a tenor with a high falsetto extension!

‘There’s None to Soothe My Soul to Rest’ (a traditional Gaelic song arranged for tenor and lute by Robert A. Smith). Randall Scotting, countertenor, and Stephen Stubbs, lute. From Lovesick.

So, we shouldn’t listen to this album as an ancient recreation, but as a modern performance. Two distinguished American artists recorded in Los Angeles, exploring 17th-century songs. And there is little that is ethereal about Scotting, standing well over a muscular six feet, he has a substantial voice, yet is a stylish interpreter of 17th-century music. He sings with a lovely burnished, well-filled line and is no stranger to warming the voice with vibrato, but his diction is excellent. This isn’t text sung on the thread of a voice, but a full, rich voice that projects text as an important contributor.

‘She Loves and She Confesses, Too,’ written by Henry Purcell. Randall Scotting, countertenor, and Stephen Stubbs, lute. From Lovesick.

Stubbs makes a fine co-conspirator. I have no idea what the two sound like live (voices tend to project far better than lutes), but as recorded they form a very balanced duo and the rich detail and timbre of Stubbs’ playing supports and surrounds Scotting’s powerfully expressive voice.

‘Time stands still,’ by John Dowland, performed by Randall Scotting, coutertenor, and Stephen Stubb, bass lute, from Lovesick.

The disc ends with an intriguing pairing. First, the traditional Scottish ballad, “Black is the colour of my true love’s hair,” in a version by the American composer, singer and collector John Jacob Niles (1892-1980) that many will recognize from versions by folk singers; but in fact this song has been recorded by many including Burl Ives, Pete Seeger, Nina Simone, Joan Baez, Cathy Berberian and Alfred Deller, showing that we can never quite take for granted how a particular song should be sung.

Then comes Purcell’s “O, Solitude” in a version that stays firmly close to the work’s ground bass. Scotting’s line unfolds flexibly in the time and rhythms provided by Stubb’s firmly walking bass, and this is definitely a lute song (rather than a larger scale version as is sometimes done in concert). The speed is, perhaps, surprising, but in the context of just one voice and a lute (an instrument without a long acoustic delay) this makes sense in context, whilst Scotting and Stubbs use the song in an expressive way.

Reviews published here by permission of Robert Hugill at Planet Hugill (www.planethugill.com), a singer, composer, journalist, lover of opera and all things Handel. To receive Robert’s lively “This month on Planet Hugill” e-newsletter, sign up on his Mailing List. (Robert Hugill photo by Robert Piwko. This review was published at Planet Hugill on 19 May 2023.

Reviews published here by permission of Robert Hugill at Planet Hugill (www.planethugill.com), a singer, composer, journalist, lover of opera and all things Handel. To receive Robert’s lively “This month on Planet Hugill” e-newsletter, sign up on his Mailing List. (Robert Hugill photo by Robert Piwko. This review was published at Planet Hugill on 19 May 2023.