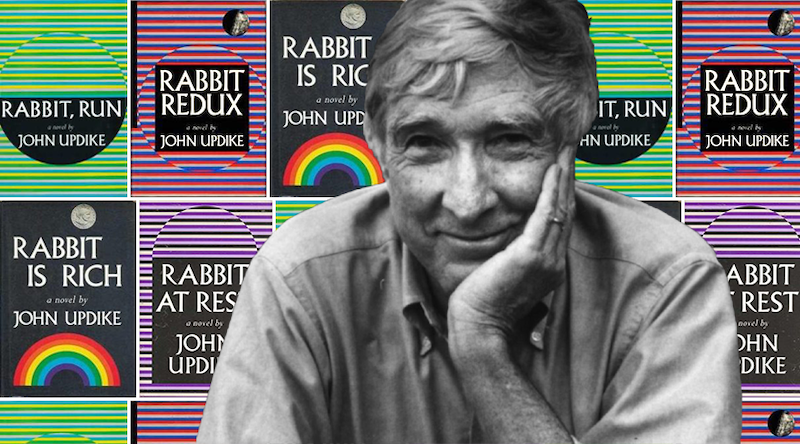

In the April 2011 issue of our predecessor, www.TheBluegrassSpecial.com, we began pondering the meaning and weight of John Updike’s poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter” via the perspectives of various theologians, ministers, religious philosophers, pundits and seminary students. A year later, in our April 2012 issue, we expanded the feature to “Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas,” and now here we are in 2023 with our 12th installment of this Easter perennial in our pages. This year’s edition is a mix of new voices and some golden oldies culled from the previous 10 years of voices weighing in and vividly illustrating in words the passions evoked and inflamed by Updike’s provocative reflection on Christianity’s defining event.

***

Seven Stanzas at Easter

By John Updike

(from Telephone Poles and Other Poems, 1963)

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft Spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That-pierced-died, withered, paused, and then

Regathered out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-maché,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

Opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

Embarrassed by the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

***

The Story Behind ‘Seven Stanzas’

By Kathleen Kastilahn

April 2001

Norman D. Kretzmann remembers John Updike as a young Harvard graduate who sought out Clifton Lutheran Church in Marblehead, Mass., because it “nurtured the roots of faith he had grown up with in Pennsylvania.” Kretzmann, pastor of Marblehead at the time, proudly recalls that Updike was among the 96 adults who entered the congregation’s Religious Arts Festival in 1960–and that his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” won $100 for “Best of Show.”

“People in the parishes I served became quite accustomed to my quoting his poem in my Easter sermons at least every few years,” says Kretzmann, who lives in a Minneapolis retirement center and regularly contributes to the Metro Lutheran newspaper.

Kretzmann closely follows Updike’s work, which includes more than 50 novels and books of poems. In a Metro Lutheran review of John Updike and Religion (Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000) he wrote: “I was John Updike’s pastor during the time which the writer later described as his ‘angst-besmogged period.’ Who was the rabbi and who was the disciple of our years together is hard to say.”

The pastor still has Updike’s 41-year-old typed copy of “Seven Stanzas”–“marked up with all sorts of irrelevant notes by me, instructions to me for homiletical purposes or for various secretaries,” he said. And Kretzmann has one more fond memory from the festival: Updike gave the $100 prize back to the congregation.

Originally published at The Lutheran.org (now defunct)

***

Seven Voices on Steven Stanzas at Easter, 2023 Edition

I

Unpacking Seven Stanzas at Easter

By Dave Schelhaas

Published April 14, 2020 at in all things, a publication of the Andreas. Center at Dordt University.

During the 1950’s, John Updike worshipped at a Lutheran church in Marblehead, MA, a church similar in some respects to the Lutheran church of his youth in Pennsylvania. When the congregation sponsored a Religious Arts Festival and offered a $100 prize for the best artwork, Updike submitted the poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” He won and received the $100 which he promptly gave back to the church and over the years “Seven Stanzas at Easter” has become a much-loved poem.

I was drawn as a reader to the short stories of Updike before I encountered his poetry, and it was the richness of his prose along with the frequent religious content that drew me. My favorite Updike piece to this day is the short story “Pigeon Feathers.” It ends with a boy (a thinly disguised young Updike) burying some pigeons he had shot. You will see in this quotation, the character’s certainty (and Updike’s hope?) that when he dies, God will raise him from the dead:

As he fitted the last two, still pliant, on the top, and stood up, crusty coverings were lifted from him, and with a feminine, slipping sensation along his nerves that seemed to give the air hands, he was robed in this certainty: that the God who had lavished such craft upon these worthless birds would not destroy His whole Creation by refusing to let David live forever.

In response to questions about his faith, Updike has said, “I have been a churchgoer in three Protestant denominations–Lutheran, Congregational, Episcopal–and the Christian faith has given me comfort in my life and, I would like to think, courage in my work. For it tells us that truth is holy, and truth-telling a noble and useful profession; that the reality around us is created and worth celebrating; that men and women are radically imperfect and radically valuable” (Yerkes 4). Serious readers will agree, based on his personal statements as well as his fiction and poetry, that Updike was a believer.

The two great theological heroes of his life were Karl Barth and Soren Kierkegaard. In 1959 while he was going through a spiritual crisis, “he got through it by clinging to the stern neo-orthodoxy of Swiss theologian Karl Barth.” In his autobiographical poem Midpoint, Updike quotes Karl Barth’s assertion that “a drowning man cannot pull himself out by his own hair.” In an interview about the poem he said that he believed this meant “here is no help from within–without the supernatural, the natural is a pit of horror. I believe that all problems are basically insoluble and faith is a leap out of despair” (Hunt 17).

The two great theological heroes of his life were Karl Barth and Soren Kierkegaard. In 1959 while he was going through a spiritual crisis, “he got through it by clinging to the stern neo-orthodoxy of Swiss theologian Karl Barth.” In his autobiographical poem Midpoint, Updike quotes Karl Barth’s assertion that “a drowning man cannot pull himself out by his own hair.” In an interview about the poem he said that he believed this meant “here is no help from within–without the supernatural, the natural is a pit of horror. I believe that all problems are basically insoluble and faith is a leap out of despair” (Hunt 17).

Updike writes that he fell in love with Kierkegaard, the Danish Christian existentialist, in his early twenties. He read the naturalistic existentialists at that time also, but they “didn’t seem to solve any problems the way Kierkegaard’s approach did” (Hunt 12).

Now, understanding more about Updike, what do we need to unpack in this poem? Let’s start with the title. Why seven stanzas? Perhaps it’s simply how many stanzas it took to say what he wanted to say, but it’s more likely that knowing seven represents completeness, he uses that number in his title to suggest the completion of Christ’s work in his resurrection.

And why that irksome if in line one? Is Updike revealing his doubt that the resurrection occurred? I don’t think so. More likely he recognizes he is writing in a secular age where many clerics and church members are explaining away the supernatural elements of their Christianity and therefore also the very possibility of resurrection. All of stanza four is devoted to chastising the liberal church for its attempt to reduce the resurrection to something explainable, something natural.

‘Seven Stanzas at Eater,’ a musical interpretation by Gregg Smith, Saint Peter’s Choir and Thomas Schmidt, from Music for an Urban Church, released 2014 on Albany records

Updike’s task in this poem is to convince readers in our scientific age that, unnatural though it be, resurrection has happened. A dominant feature of the poem is its use of scientific language as a way of establishing what happened when Christ arose and what will happen when we are resurrected: “molecules will reknit,” “amino acids rekindle.” Just as he had before he died, the resurrected Christ will have a “hinged thumb,” “valved heart,” and so forth. If this is not the case, the “church will fall.”

I have always been puzzled by that angel in stanza six “weighty with Max Planck quanta.” What in the world does this mean? My friend, physicist John Zwart, says, “the idea of light quanta (or photons as they came to be called) fundamentally changed our understanding of the creation . . . Planck’s ad hoc assumption that the energy of light was not a continuously variable quantity, but instead came in integer multiples of hf. . . became one of the fundamentals that physicists and other science folk use to understand the creation.”

Zwart concludes, “I expect that Updike is expanding on his ‘make it a real angel’ by stating that the angelic light is real light as we currently understand it.” (I thank you, John, for helping me to understand this puzzling line.)

Updike ends stanza four with “Let us walk through the door,” thus urging us to enter into the world of faith, the world of those who believe in the resurrection. Stanza five, beginning with “The stone is rolled back. . . ” reveals the open door of stanza four.

At the same time, the stone continues the theme of realism. After insisting that it is a real stone, Updike asks that it also be seen as the vast rock of materiality that “will eclipse for each of us/the wide light of day.” In other words, all of us are going to die and this death as well as a gravestone or some other material substance is going to eclipse for us “the wide light of day.” But, in the day of resurrection we shall walk through the door that Christ opened into eternal life.

In the last stanza we find two words with the same Latin root, monstrum: “monstrous” and “remonstrance.” Here, it seems to me that Updike, like the metaphysical poets of old is making a complex pun. The first meaning of “monstrous” is “large, huge, enormous.” The common meaning of “monstrance” is (from the Roman Catholic Church) “a receptacle in which the consecrated Host is exposed for adoration.” Taking these words as they are used in the last stanza, we might paraphrase them by saying, “Let us not diminish the enormity of the Biblical account of the resurrection, for if we do we might in the day of resurrection be deeply shamed, by the reappearance of the living host, Jesus Christ. If we have doubted the reality of the resurrection, we might be filled with remonstrance, that is, shame and regret, when we see the little communion wafer next to the life-sized Christ (the monstrance eclipsed by Re-monstrance).

“Seven Stanzas at Easter” is not an especially lyrical poem, though Updike is capable of marvelous lyricism. Rather, it is down-to-earth in its tone and language (except for one marvelous pun). Updike does not intend to charm us with flights of eloquence, great swaths of words that roll over us like ocean waves. Nope. His language here is scientific, prosaic, as down to earth as hinged toes.

Works Cited

Hunt, George W., S. J. John Updike and the Three Great Secret Things: Sex, Religion, and Art. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1980.

Yerkes, James. John Updike and Religion. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999.

About the Author: Dave Schelhaas is Professor Emeritus of English at Dordt University.

***

The Empty Tomb (Mikhail Nesterov, 1889)

Steadfast and Immovable

John M. Buchanan

Pastor, Fourth Presbyterian Church

(Excerpt from a longer sermon delivered on Easter Sunday, April 12, 2009 and published at the Fourth Presbyterian Church website, www.fourthchurch.org)

John Updike wrote a wonderful poem in 1961 for, I am happy to say, the Christian Century: “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” Updike was a very distinguished author, essayist, literary critic, and poet. He was also a believer, a church member, a Sunday School teacher. He died on January 27, and those of us who were regularly enriched by his writing greatly miss him. ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter” will find its way into a lot of Easter sermons this year I suspect:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

Updike has walked through that door. Remarkably, in his last months of life he wrote a group of wonderful poems, which were published in the New Yorker after he died. When he realized he might be seriously sick, he wrote,

How not to think of death? I see clear through to the ultimate page . . . Be with me, words, a little longer.

He wrote the last poem December 22; he thinks about Sunday School and Christmas pageants, the ordinary mystery of ordinary people believing and trusting, and concludes, in the last lines he ever wrote, remembering the words of the beloved Twenty-Third Psalm:

Surely—magnificent, that “surely”—goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, my life forever.

That’s it finally. Because Jesus Christ is risen, because of Easter, we know surely that mercy shall follow all the days of our lives and the lives of our dear ones and beyond, forever.

The Gospel says simply that when that astonishing day was over, Peter and John returned to their homes. So may we return to our homes, our lives in the world, steadfast and immovable, with resolve to follow him all the days of our lives, with laughter and great joy in our hearts.

For Christ our Lord is risen. He is risen indeed.

Amen.

Sermon © Fourth Presbyterian Church

***

III

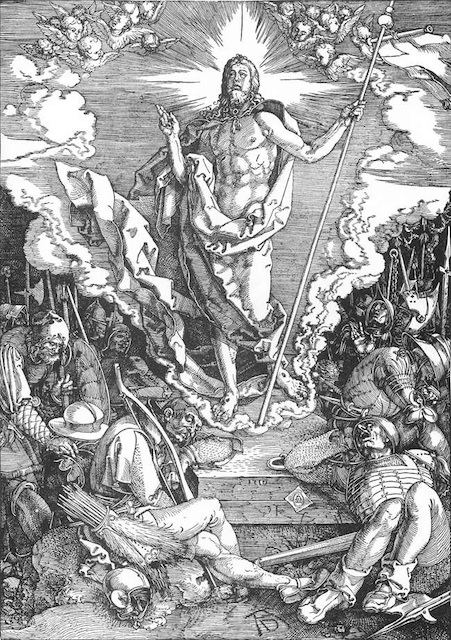

The Resurrection of Christ by Albrecht Durer, 1510

‘Without the Resurrection, Jesus Was Just Another Wise Teacher’

PASTOR’S PONDERINGS, MARCH 2011

Rev. Dr. Bradley J. Donahue

The celebration of Easter is as late as can be on the calendar so we have a better chance this year of warm weather for Easter Sunday. Likewise Lent starts later so we have spent more time in the church season of Epiphany then we usually do.

Both occurrences can be a little unsettling for us, we are not use to such lateness in the church calendar. We usually move through the seasons fairly quickly. But not this year, this year Easter will take its own sweet time coming.

Church historian tells us the in the early church Easter not the celebration of Christ’s birth was the most important holiday. The early church was slow in recognizing the celebration of Christmas. There is some theological soundness in this. I love Christmas but what is most significant to the faith is that God worked a marvelous miracle on Easter morning.

Without the resurrection, Jesus was just another wise teacher, who taught some very important things.

What sets him apart from all others is the proclamation of the angel, “He is not here. He is risen.”

American author John Updike in his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter” writes:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

Maybe Updike has a point, maybe we don’t take the power of the resurrection seriously enough.

It was the event that drove the early church and empowered them to proclaim the good news.

As we enter Lent 2011 perhaps this would be a good time to reflect on what the Resurrection means for us.

1 Cor 15:14-17

…and if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain. We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified of God that he raised Christ-whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.

Grace and Peace,

Dr. Bradley J. Donahue

VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3

TEMPLE TALK

Originally posted at the website of Lorain Christian Temple Disciples of Christ, Lorain, OH

***

IV

‘Uncompromisingly Biblical’

By Tom Grosh IV

When considering the correspondence theory of truth in Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice (Christian Worldview Integration Series. InterVarsity Press. 2011), David Lyle Jeffrey and Gregory Maillet refer to John Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter” (1960). *Enjoy this excerpt from a “bold, wonderfully learned manifesto … [which] breathes a prophetic passion — bracing, salutary and sometimes uncomfortable — that transcends mere academic discussion and leaves the reader interrogated as well as taught.” (Dennis Danielson, Professor of English, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and editor of The Cambridge Companion to Milton. at InterVarsity Press.)

Historically, the predominant way of looking at truth is the one that occurs first to common sense. According to the correspondence theory of truth, a verbal claim is true only if it corresponds to pertinent fact or external reality. If there is no correspondence (e.g., if I claim that the sky is falling and some of my students run outside to check and confirm, sensibly, this it is not), the claim is evidently false at the literal level. On this view, if a speaker or writer claims that the earth is flat or that it will come to a catastrophic end in Y2K (A.D. 200) or that drinking a certain beverage will make us irresistible to the opposite sex, there are ways to investigate the veracity of each claim.

Even when we account for variance in the way people see things, this theory tends to apply to most situations quite serviceably. In each case of this sort, actuality (or as we might say, reality) takes precedence and is indispensable to the claims made regarding it, as well as the plausibility of inferences that may be drawn or actions recommended in consequence. In a famous example from the New Testament, St. Paul insists that if Christ did not literally rise from the dead, then all discussions of the event and our faith in it are meaningless and a waste of time (1 Cor 15:12-20). The poetic commentary of John Updike in his “Seven Stanzas at Easter” (1960) is thus historically and logically on the mark when he says

if he rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle

the Church will fall.

Updike is in this poem uncompromisingly biblical in his insistence on a correspondence theory of truth; no soft metaphorizing of the resurrection, given the explicit factual claims of Scripture and the church, can be other than a lie-–especially if created, as Updike says, “for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty.” Updike was in this poem reacting to common liberal theological platitudes and, in the fashion recommended by Paul to Titus, giving such revisionary constructions a stiff rebuke. To turn the essential truth given in historical event into an evasive and naturalistic trope is here to pervert the proper business even of poetry, especially for the poet who wants to think like a Christian.

About Tom Grosh IV: Enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa, four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church, on campus as part of InterVarsity’s Graduate & Faculty Ministry, in the culture at large, and in God’s creation.

About Tom Grosh IV: Enjoys daily conversations regarding living out the Biblical Story with his wife Theresa, four girls, around the block, at Elizabethtown Brethren in Christ Church, on campus as part of InterVarsity’s Graduate & Faculty Ministry, in the culture at large, and in God’s creation.

***

V

‘What Door Now Stands Open?”

excerpt from Easter Day Sermon 2004

by the Bishop of Meath and Kildare,

the Most Revd Dr. Richard Clarke

at St. Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare, Easter Day, 11 April 2004

Revelation 3.8 “I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

Richard Clarke

The Gospels are of course certainly talking about the Resurrection as a real event, an event in human history. There is, as we know, a condescending and superior approach to the whole matter which suggests that the Gospel writers were speaking of a symbolic resurrection, that Jesus remained very much dead, and that what we call Easter was merely a realization on the part of the disciples that this man Jesus Christ was possibly on the right lines after all. His resurrection was in their heads and in their imagination, but nowhere else. This is, it seems to me, staggeringly patronizing–patronizing about the Gospel writers who would have known perfectly well how to make it clear if they were writing metaphor, patronizing about generation upon generation of great Christian thinkers and writers who were in fact not gullible idiots, patronizing about us who don’t like to think of ourselves either as fools or as fantasists. It’s actually patronizing about God as well. As the American writer and poet John Updike puts it so neatly, in one of his “Seven Stanzas at Easter,”

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

faded credulity of earlier ages;

let us walk through the door.

The question accordingly becomes a matter, not only of the objective reality of Resurrection, but also of the impact on the lives of disciples. disciples of the twenty-first century as of the first century–of how disciples walk through this door of which both the writer of the Book of Revelation and John Updike speak to us. The question becomes, “What effect does the resurrection of Jesus Christ have on our lives?” “What door now stands open?”

*The Resurrection means first that, as individuals, we must look at Christ in a different way. Mary Magdalene, who had loved and admired him before, now finds herself utterly transformed by him. She becomes different, because everything falls into place. All that he had said and had done were no longer the words and actions of a good man, even the best man there had ever been, it had all been given an eternal reality for her which could not be contradicted or ever destroyed. No matter how often we are told that it will not do to patronize Christ, and to treat him as an amiable carpenter with a good line in stories (who would however not have survived for very long in any real grown-up world), we still do it. The resurrection is the playing of the trump card which tells us that if we not treat him with the utmost seriousness and with total reverence, it is we who are the buffoons.

*It means also that we cannot look at others in the same way. Most of the resurrection stories are stories of Christ’s friends meeting together–in a room, in a boat, on a beach, walking to a village. The Easter event is about sharing faith, being part of a community which celebrates the presence of Jesus Christ. We are pushed again and again in the Easter stories to realize that Christ is real and present with us in the Eucharist, the meal of the Church, as he shares food in a village room, as he asks for food on a shore, as he eats with his disciples in a room in Jerusalem. The risen Christ joins with his followers as they meet together. This is why it is so immensely foolish to imagine that we are somehow doing God a favor when we turn up in church for a service. Worship should never be seen as anything other than an immense privilege to be treated with the greatest humility and reverence, as the God who created us, who keeps us in being and who has smashed through the dreadfulness of death ahead of us, is ready to join us as companion and friend. Christian worship, Christian community and Christian fellowship become Easter gifts to be prized and revered, and for which we should be ever and profoundly thankful to God.

*It means that we can face ourselves in a new way. What are we as individuals without the resurrection? A moderately sophisticated organism which, simply because it has a thing called a “mind,” gets ideas far above its station, but which nevertheless ceases to exist after a few brief spins of a grubby little planet around the nearest, rather insignificant star. It is God in Christ, God in the risen Christ, who gives us a real dignity and a true purpose. This is not the bogus dignity we so readily give ourselves. This is the dignity of being a child of God, given a function and given a purpose to bring others into loving fellowship with him. I have no doubts that the value of our earthly life will be measured in the context of eternity, neither by how much we accumulated for ourselves, nor by how much others feared us or envied us, but by how much more Christian this world became, because we lived in it. And this conviction, if you think about it, only makes any sense in the light of Easter.

Easter is of course far, far more than a good reason for being a Christian. This is why we must never trivialize it, or reduce it to a happy ending or a pious parable. It is an open door to faith, to hope, to love, and thus to the fullness of eternal life.

“I have set before you an open door which no one can shut.”

Published at Diocesan News-Church of Ireland

The Resurrection, Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), circa 1715

***

VI

‘A Sermon Without Reason’

By Rev. Bruce Bode

(excerpt from a longer sermon delivered on October 26, 2014 at Quimper Unitarian Universalist Fellowship and posted at www.quuf.org)

For years I’ve been carrying around with me a poem from the modern novelist John Updike, the novelist most well-known for his Rabbit series of novels; he died in 2009. And the poem I carry with me has to do with this notion of breaking the hold of the rational mind through believing something that is unbelievable.

I’ve never quite known what to do with this poem, but now I think I’ve found the spot for it. It’s titled, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” and has to do with believing in a literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus.

Is John Updike, this modern, scientific person, really behind this?

Does he really believe in a literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus?

Perhaps so, as there are many modern, scientifically-minded people, who compartmentalize religion, who, for whatever reasons, have areas that are, let us say, “unreconstructed” by modern thought. And, perhaps, this is the case with John Updike.

But mainly I see this poem as Updike protesting against religion that thinks that it can explain everything, that is too rational in its orientation, too much of the head and not enough of the heart, soul, and body.

And this would be a charge that Updike would level against liberal religion, which has emphasized the use and value and importance of reason and thought and science in relation to religion.

But here I believe that Updike, who I appreciate in many respects, is taking us down a wrong path, pitting religion against science and modern cosmology. In protesting against what he regards as the dry rationality of liberal religion, he has dismissed science–and that is not good either for science or religion.

My own main mentor in the ministry, Dr. Duncan Littlefair, after a lifetime of reflecting on the relation of science and religion, came up with a two-part formula that goes like this:

“Part I: To the extent that religion dismisses science, it is invalid.

Part II: To the extent that religion depends on science, it is invalid.”

In Updike’s poem, it would seem that he is dismissing science and modern thought. He calls upon us to “walk through the door,” but I think he’s got the wrong door. He seems to want us to walk through the door into scientific absurdity and irrationality.

So I want to suggest another option, not the door into scientific absurdity and irrationality, but the door into non-rationality and mystery, the kind of mystery that a scientist like Albert Einstein was seized by and spoke of in words such as these:

“The most beautiful and deepest experience a person can have is the sense of the mysterious. It is the underlying principle of religion as well as all serious endeavors in art and science. Anyone who never had this experience seems to me, if not dead, then at least blind. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is a something that our mind cannot grasp and whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly and as a feeble reflection, this is religiousness. In this sense I am religious. To me it suffices to wonder at these secrets and to attempt humbly to grasp with my mind a mere image of the lofty structure of all that there is.”

In this regard, theologian Paul Tillich speaks of two different kinds of “mystery.”

The first kind is the mystery of a puzzle: something not yet known but which could be known; something not yet solved but which could be solved. It’s the kind of mystery that you get in a “mystery novel.” You read the mystery novel to unravel the mystery. The unsolved puzzle carries you until the end when, finally, the mystery is solved; and once solved, the mystery is dissolved–no more mystery.

But there’s a second kind of mystery that is never solved, and this is the kind of mystery that Einstein is talking about. It’s the mystery of being itself, what the Buddhists call the “suchness” of things.

This is the mystery that of its nature cannot be solved. Indeed, one’s sense of mystery–and one’s awe and wonder in the face of the mystery–only deepens as you learn more about its reality. The more you understand, the less you understand. The deeper you probe, the larger grows your sense of wonder. The keener your mind, the greater your humility.

And this is the mystery that religion is–-or ought–-to be, first of all, about.

The Ascension of Christ, Rembrandt (1636)

VII

‘This Is Poetry in Action’

By Judge Bill Swann

I wrote some lines earlier in Five Proofs of Christianity (WestBow, 2016):

I know as a Christian that Easter is our bedrock. Thirty-three years after the birth of Christ the resurrection occurred, without which, as Paul says, we are nowhere. Our hope is in vain. And we are of all people most to be pitied because we have believed in vain, Easter is for me a coldly rational, magnificent moment.

Perhaps I was wrong. Easter need not be a coldly rational moment, at least not from John Updike’s perspective. Its s a monstrous, shocking moment, literally true in its screaming scientific detail; impossible but true. It is not to be toned down, rationalized, prettified. It is to be confronted and accepted or confronted and fled. There is no compromise:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

Christ rose from the grave, Updike says, with the same hinged thumbs and toes we ourselves have, the same valved heart we have—but with Christ it was a heart that had been pierced, a heart that had died, that withered, and then regathered new strength.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable

No, says Updike, it is Christ himself, body reconstituted, raised from the dead who emerges when the stone is rolled back. A real stone, the same stone which for each of us will someday eclipse our own wide light of day, just as it did for Christ.

John Updike (1932-2009) wrote this 35-line poem in 1960 while attending a Lutheran congregation in Marblehead, Massachusetts. He entered it in the church’s poetry competition, won its hundred-dollar prize, and gave the money back to the congregation.

![Updike at Easter (2023 Edition) 11 Dailey & Vincent - By the Mark (Live] ft. Bill & Gloria Gaither](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Dw-uklIlQE0/hqdefault.jpg)

‘Visceral clarity’: Dailey and Vincent, ‘By the Mark,’ written by David Rawlings and Gillian Welch

He was twenty-eight years old and already wise enough to see, as many gospel singers do, the view from inside the cave, the end of our daylight, approaching death, “the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of time will eclipse for each of us the wide light of day.”

This is visceral clarity Jamie Dailey and Darrin Vincent deal out in “By the Mark,” a new gospel song.

More than fifty years have passed since Updike wrote his poem, and still it drives our thoughts. It makes us decide. This is poetry in action. Christ is for real, or he isn’t. We must decide.

—Excerpt from Politics, Faith, Love: A Judge’s Notes on Things That Matter by Judge Bill Swann (Balboa Press, 2017)