Editor’s Note: Attentive Deep Roots readers are aware of our acclaimed kids’ lit blogger Jules’s (Julie Danielson) decision to shutter her Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast blog. However, since books have a longer “shelf life” than records, we will continue publishing 7 Imp for some period of time, drawing on the trove of features she’s published in the past year or so that did not appear in Deep Roots when originally posted. We blame this on Jules—she uncovered so many great books for young readers that we simply could not cover them all adequately. So, with her permission, we’re keeping Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast alive in Deep Roots, for the time, by mining the 7 Imp archive for treasures unpublished.

Jules (Julie Danielson)

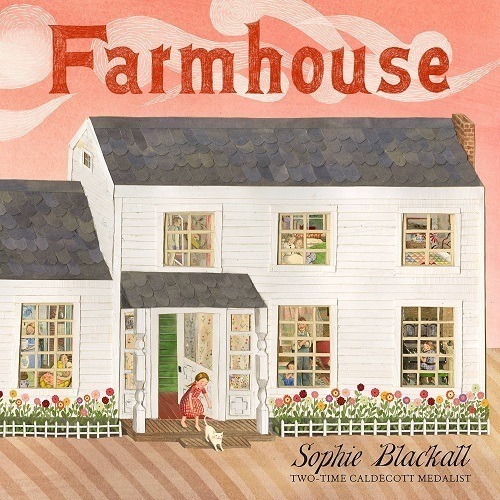

This month’s installment is Jules’s final, official 7 Imp blog, and let us say she is going out in style—it is arguably her finest hour. The book is titled Farmhouse, by Sophie Blackall. It seems simple: From the confines of her and her husband’s upstate “creative retreat for the children’s book community,” called Milkwood, Ms. Blackall spotted through a clearing in the landscape a dilapidated farmhouse, a “falling-down house,” as she refers to it. It’s when she goes to the house and discovers evidence of its previous inhabitants that things get interesting, very interesting. Here’s how she puts it in the book:

“The very first time I stepped inside the house, pushing my way through nettles and weeds and tangled vines, I knew there was a story here. Not just the story of this particular house, or of a family with 12 children growing up during the Great Depression, or of the plight of small farms across the country — but about how a place can hold the stories of the people who pass through it, long after they’re gone, and how those stories connect us to the past, to the people who came before us, and before them, and before them, and to those who will come after us, layers of stories, like the peeling wallpaper I found in the house.”

It gets more interesting with each succeeding paragraph as Ms. Blackall sets out on her self-appointed mission to “preserve the stories, to honor the house before it returned to the earth.” As Jules notes below, ‘This book. It’s a thing of beauty.” Not wanting to spoil the emotional impact the author achieves in documenting her journey, we’ll leave it at that and urge readers to behold the riches Jules and Ms. Blackall offer in this, Jules’s presumable sign-off from Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast. Frankly, we can’t image Deep Roots without it. Thanks for enlarging our world in so many positive ways, Jules. —D.M

***

Hey, imps. If you read my official farewell post — in which I announced that I’m finally going to sit down for some breakfast (which is, delightfully, how Siân Gaetano put it on Instagram)–you may remember that I said I had one more post left. That is today’s post in which author-illustrator Sophie Blackall visits to talk about the making of Farmhouse (Little, Brown, September 2022), which I reviewed over at BookPage.

This book. It’s a thing of beauty. Thanks to Sophie for visiting and sharing so generously.

***

Sophie: I first visited Jules here at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast way back in 2008, and it is such a privilege to be invited back again, at the end of an era, to chat about Farmhouse.

Thank you, Jules, for giving so many of us the opportunity to talk about our books and our processes and our lives–and for building an archive of interviews where we can learn how other people make their books and live their lives. You have given us an extraordinary gift.

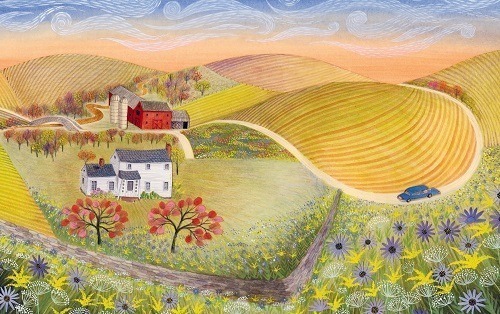

I am writing this on a late summer morning from Milkwood, the creative retreat for the children’s book community in upstate New York that my husband, Ed, and I opened this year. Through the open door I can see hills and fields sloping away to a glittering stream that twists and turns through the trees.

(Click image to enlarge)

There’s a clearing amongst the trees, where there used to be a farmhouse, a falling-down house that inspired the book I am excited to tell you about, Farmhouse.

(Click cover to enlarge)

The very first time I stepped inside the house, pushing my way through nettles and weeds and tangled vines, I knew there was a story here. Not just the story of this particular house, or of a family with 12 children growing up during the Great Depression, or of the plight of small farms across the country — but about how a place can hold the stories of the people who pass through it, long after they’re gone, and how those stories connect us to the past, to the people who came before us, and before them, and before them, and to those who will come after us, layers of stories, like the peeling wallpaper I found in the house.

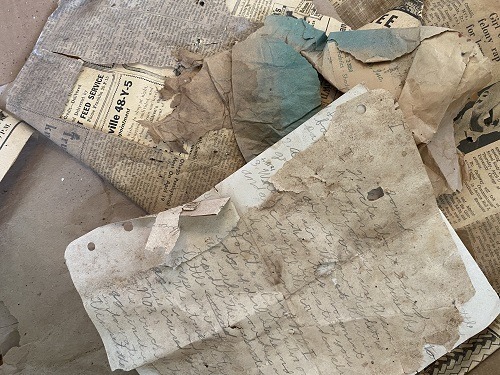

(Click image to enlarge)

Once I began exploring the falling-down house, I couldn’t stop, even though it was a little foolhardy. The ceiling was open to the sky. A sapling was growing in the kitchen. The basement had caved in, and more than once I put my foot through the floor. But there were stories to collect! I gathered sheaves of wallpaper scraps, moldy old school books, and even 21 hand-sewn dresses that were covered in mud and leaves that I hung in a tree to dry.

(Click image to enlarge)

I wanted to record everything I could to preserve the stories, to honor the house before it returned to the earth. And as my piles of things grew, I realized I could use these actual materials to make the pictures, that the fabric and wallpaper and pages from school books could be used to build the house in the book. And that I could make the experience of reading this book feel as close as possible to the experience of being in the farmhouse, that you would follow the story from page to page and slowly realize you were making your way through the house and through time, room by room, that everything that was happening was connected, that the celebrations and arguments, moments of grief and of joy had all become part of the house itself.

(Click image to enlarge)

Around this time I realized with a thud that, while I knew what I wanted to say, I had no idea how to write it. I had written draft after draft and, though my beloved editor Susan Rich was very patient (and I mean VERY PATIENT), I could tell she was beginning to worry. Deadlines were looming. So this is what happened.

I was driving down to the Virginia Children’s Book Festival, a seven-hour drive from New York City, and the engine of my old car began to make an ominous sound. I called a mechanic in Farmville, Virginia, and they said they could look at it if I could get there by 5 p.m. It was noon on the dot and Google said it was a five-hour drive. If I didn’t stop–and if I didn’t break down—I could make it.

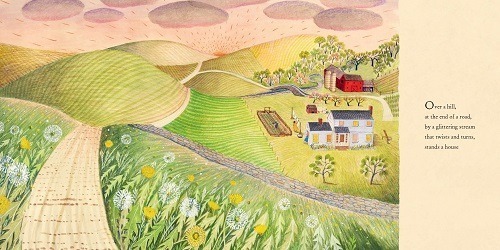

Hunched over the wheel, I turned my thoughts to Farmhouse. If only I could get the first line, if only I could find my way in. Then the line came: “Over the hill, at the end of a road, by a glittering stream that twists and turns stands a house …”

I couldn’t stop to write it down, so I kept saying it over and over. And as I repeated it, I would add another phrase. Over the hill, at the end of a road, by a glittering stream that twists and turns stands a house where twelve children were born and raised…

I pulled into the mechanic at 4:59 p.m, threw him the keys, spoke the whole long sentence into my phone, and sent it to Susan.

I still have that voice message and the book is still one long sentence.

“Over a hill, at the end of a road, by a glittering stream that twists and turns, stands a house …” (Click spread to enlarge)

The road to Milkwood (Click image to enlarge)

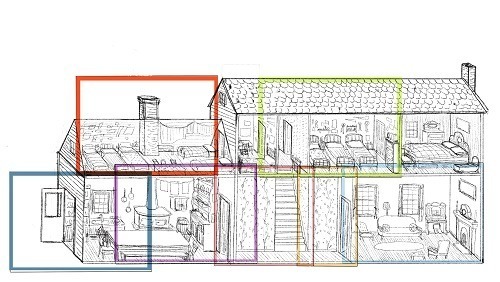

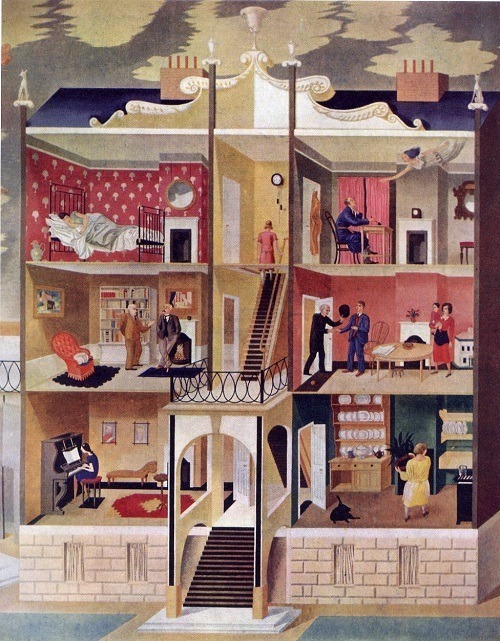

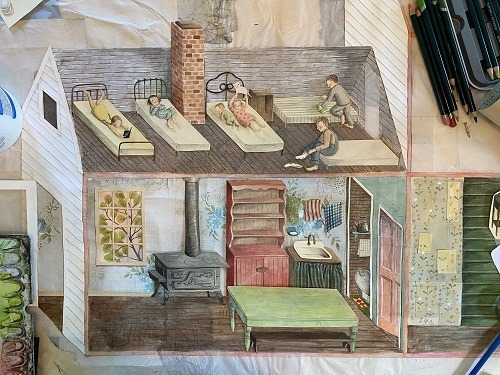

Once I had the story written in actual words, I could get going with the illustrations in earnest, but first I needed a plan. I used the original layout of the house and drew a cutaway, or elevation, then placed a frame that was the proportions of a double-page spread over the sketch of the house to figure out how I would use different rooms to stage each scene and move through the farmhouse so that each page would connect. I color-coded the frames. It was a fun puzzle.

(Click image to enlarge)

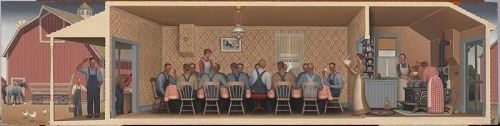

I came across this wonderful painting by Grant Wood called Dinner for Threshers, which gave me all sorts of ideas…

(Click image to enlarge)

… and this beautiful mural, lost in a bombing in World War II, by Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden:

(Clock to enlarge)

I bought up old books of Farm Security Administration and WPA photographs of rural America and pored over pictures of families living in incredible poverty.

(Click image to enlarge)

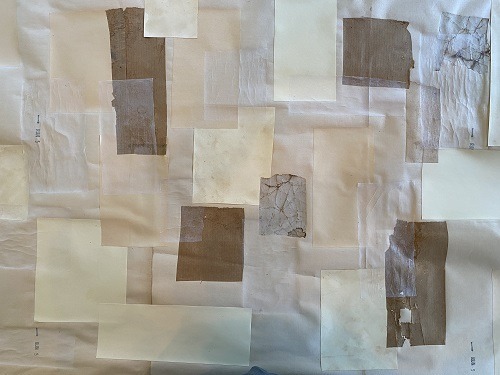

Then I drew up the elevation of the house on a giant roll of tracing paper and, because I knew I wanted a lot of detail in there, the drawing was enormous! It took up my whole studio table. At this stage, I had a decision to make. If I was going to make all the pages join up as though we were moving through the house, then the house needed to be one giant, layered piece of art. And once I began making this house, I wouldn’t be able to move it. I would be pretty much stuck in one place until I finished it. I decided to work on it in the country, near the site of the falling-down house. Spreading out my enormous tracing paper drawing, I had the feeling it needed some history behind it, so I unfurled a roll of wallpaper I found in the attic of the old house and turned it over to the blank side which was a pleasing sludgy color, speckled with age and damp. I began to arrange scraps of paper over the surface — newspaper, rumpled paper bags, more wallpaper — and I glued these layers down. Then I brushed the whole surface with wallpaper paste and lay the tracing paper house elevation on top of that, smoothing out the wrinkles. At this point, I thought I should let Susan know what I was up to. I wrote to her: “I’ve been thinking about the layers of a house, the generations of inhabitants, layers of memories, and actual physical layers of paint and wallpaper. And how that begins to peel away as it disintegrates and the layers become exposed again, as though we are going back in time. And I’ve been thinking of the word palimpsest, which I think refers more to layers of writing but is the same idea. And so the fabric of this house is built of many, many layers of paper scraps I found in the rubble.”

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

(Click image to enlarge)

Most of these layers are invisible now, but I know they’re there.

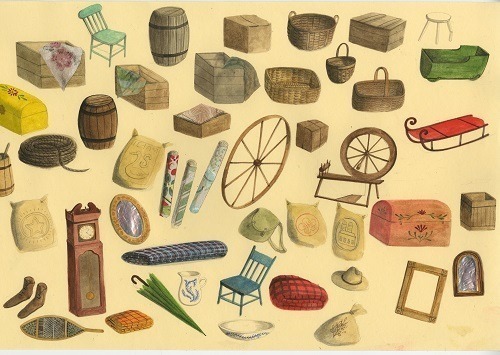

Just as I was hitting my stride, working long hours into the night and stooped over my house, my body rebelled and I came down with shingles. I was bedridden for weeks and, for weeks after that, I could only manage a few hours a day at my desk. So I worked on details from bed, painting and cutting out tiny dishes and shoes and fish, napping amongst the offcuts. It was a slightly delirious time as summer turned into fall and I immersed myself in my falling-down house with my paper family.

Details to be cut out (Click image to enlarge)

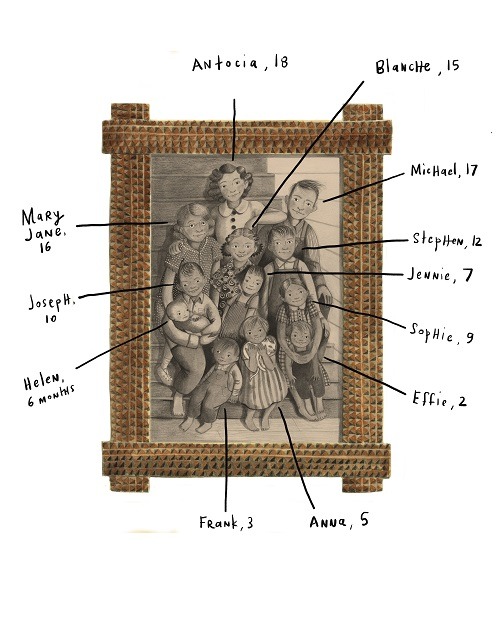

I had spent many hours talking to surviving members of the Swantak family, whose family had lived on the farm for generations, and they had been generous with their time and memories. I knew the names and birth dates of the twelve children and began to imagine and draw them. I pored over the disintegrating school books they left behind with their earnest compositions in wonky cursive and wondered about what sort of adults they grew into and whether they had dreams–and whether those dreams came true. And I thought about my own children, now young adults, and how–when I look at them–I see the wobbly-headed babies they once were. And the hilarious seven-year-olds, the curious 11-year-olds, the anxious 15-year-olds, and the confident 18-year-olds. We are all palimpsests, writing and rewriting ourselves.

Sketch of the children in Farmhouse (Click image to enlarge)

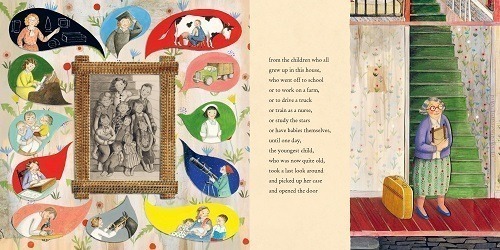

The children’s portraits (with names) (Click image to enlarge)

The final spread in the book (with the portrait): “from the children who all grew up in this house, who went off to school or to work on a farm, or to drive a truck or train as a nurse, or study the stars or have babies themselves, until one day, the youngest child, who was now quite old, took a last look around and picked up her case and opened the door” (Click image to enlarge)

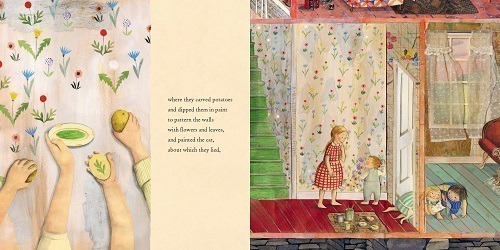

I knew I wanted the children to make potato-print wallpaper, which was something my mother did with my brother and me. I did some samples with potatoes, but the scale was too big, so I switched to stencils. The keen reader will notice the area of wall printed by the youngest, shortest children is more exuberantly stamped than the higher reaches.

Potato prints (Click image to enlarge)

Stencils (Click image to enlarge)

The final spread in the book (with the walls): “where they carved potatoes and dipped them in paint to pattern the walls with flowers and leaves, and painted the cat, about which they lied …” (Click image to enlarge)

I began to incorporate fabric from the hand-sewn dresses into the illustrations, like the skirt below the kitchen sink.

(Click image to enlarge)

The curtains in the living room were made from the real, old curtains in the house. Meanwhile, I was sewing full-size curtains for windows in the real barn, which we were transforming into bedrooms for future Milkwood guests. As I was arranging paper furniture in Farmhouse, we were moving real furniture into rooms at Milkwood. It was all a bit meta.

Curtains in the book (Click image to enlarge)

Sewing curtains for Milkwood (Click image to enlarge)

The Goat Room at Milkwood (Click image to enlarge)

The Farmhouse rooms (Click image to enlarge)

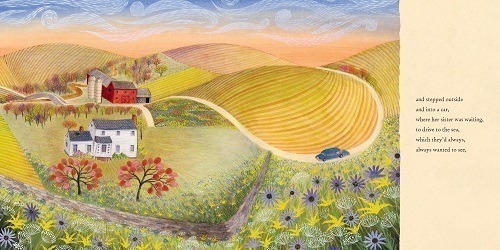

By now I was well enough to go outside again and I was documenting the landscape and painting the exterior spreads. Inside, at Milkwood, I was painting murals, practicing those rolling hills.

(Click image to enlarge)

(Clock image to enlarge)

The departure spread in Farmhouse: “and stepped outside and into a car, where her sister was waiting, to drive to the sea, which they’d always, always wanted to see …” (Click image to enlarge)

Painting the mural at Milkwood (Click image to enlarge)

As the book began to take shape, I realized I wasn’t sure about the ending. Susan and I had talked and talked about where this story needed to go, but I couldn’t figure out how to get there. The real falling-down house had well and truly fallen down. A bulldozer had come and crunched it up in its great big jaws, and the house had been buried in a giant hole.

The thrill of the bulldozer aside, wasn’t this too sad a place to end? After all the life that had filled this house and the previous pages? And then Susan, genius that she is (or maybe it was her husband, the writer Josh Greenhut–as with many of the best ideas, no one can quite remember who the genius was), had an epiphany: “You have a real, true story about the falling-down house. And it is this: before it crumbled to nothing, you collected its papers and fabrics and made it into a book. This book.”

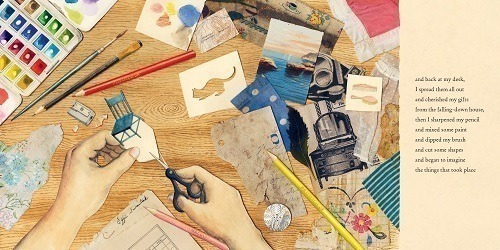

A final spread from the book: “and back at my desk, I spread them all out and cherished my gifts from the falling-down house, then I sharpened my pencila and mixed some paints and dipped my brush and cut some shapes and began to imagine the things that took place” (Click image to enlarge)

The idea, of course, is that houses fall down and people grow old and most things come to an end, but stories live on, long after we’re gone, so long as they’re told.

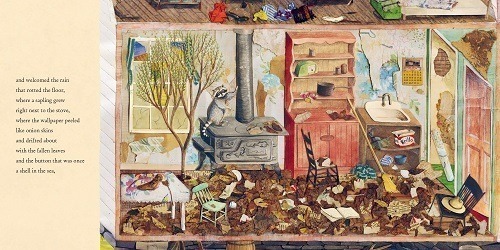

A final spread from the book: “and welcomed the rain that rotted the floor, where a sapling grew right next to the stove, where the wallpaper peeled like onion skins and drifted about with the fallen leaves and the button that was once a shell in the sea …” (Click image to enlarge)

The last spreads I worked on were the ones where the house becomes derelict. I made the decision to ravage the actual artwork, to peel back the wallpaper and crack the windowpanes and break down the surfaces. I had to steel myself a little bit, because there was no turning back once I started, but it felt right. I began painting and cutting out tiny dried leaves to scatter on the floor and realized with a clap to the forehead that the ground outside was covered in them and I could use real leaves.

Snow fell and covered the buried house and when it melted with the spring, I scattered wildflower seeds in its place. Susan sent a hammock, which swings where the house once stood.

(Click image to enlarge)

We salvaged the front door from the house, which is now the front door to the barn, which is now Milkwood:

(Click image to enlarge)

And, already, so many people have come through this door and told so many wonderful stories and added their books to the library–and brought new life to this farm.

The inaugural retreat group (Click image to enlarge)

There’s a moment in Finding Winnie, written by Lindsay Mattick, when Cole says, “Is that the end?” And his mother says, “Sometimes you have to let one story end so the next one can begin.” Many people have told me over the years that this idea has been meaningful to them in times of transition — growing up, leaving a house, ending a blog.

A new beginning–and new stories–are thrilling, but the wonderful thing about stories is that we can read them–and tell them–again and again.

I just spent a very happy hour on this blog, dipping into random interviews and 7-imp “kicks,” reading comments from people who are no longer with us, feeling how lucky I am to be part of this wonderful community. I am so grateful to Jules for leaving us this treasury–to read and reread so long as we live.

FARMHOUSE. Copyright © 2022 by Sophie Blackall. Published by Little, Brown, New York. All images and videos here reproduced by permission of Sophie Blackall.

This video about Farmhouse includes some more making-of kinds of glimpses: