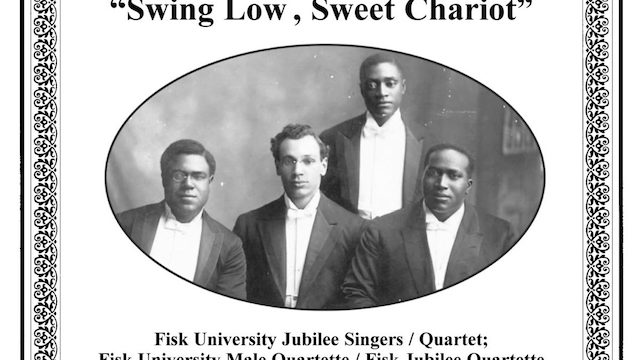

The original Fisk University Jubilee Quartet (from left): James A. Myers (second tenor), Noah W. Ryder (second bass), Alfred G. King (first bass, standing) and John W. Work II (first tenor). This quartet is featured on the Jubilee Singers’ earliest recordings.

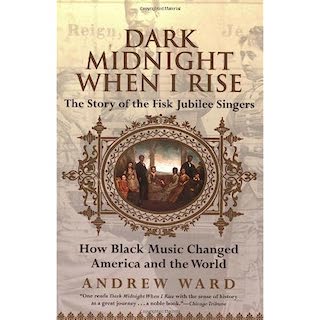

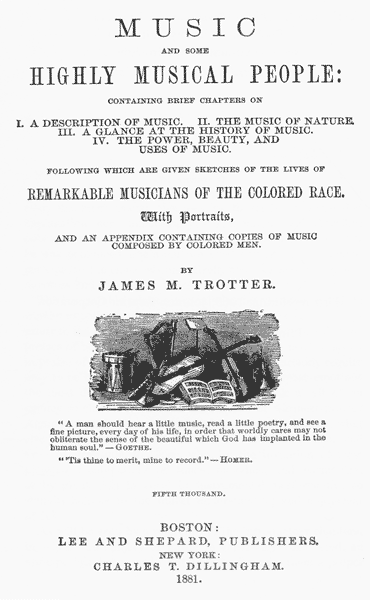

Editor’s Note: The Fisk Jubilee Singers have now been in existence 152 years. Superlatives weighty enough to describe their profound, lasting contributions to American music fail us. In this Black History Month, it behooves us to note the Singers’ difficult journey “from whipping post and auction block to concert hall and throne room,” in the words of the Singers’ biographer Andrew Ward, writing in his definitive history Dark Midnight When I Rise: The Story of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, Who Introduced the World to the Music of Black America (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2000). Mr. Ward was not the group’s first biographer; to G.D. Pike goes that honor, via his 1873 chronicle, The Jubilee Singers and Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars, focused on the near-mythological, trying concert tour the Singers undertook in 1871 to literally fund and make solvent Nashville’s Fisk University. Seven years later, however, journalist James M. Trotter published the remarkable, and invaluable, Music and Some Highly Musical People, comprised of several elements but most importantly, in its own words, “sketches of the lives of remarkable musicians of the colored race.” Chapter 19 of Trotter’s book, devoted solely to the Jubilee Singers, expands upon Pike’s account with fresh reporting and, obviously, a longer timeframe for appraising the results of the wildly successful—against all odds—1871 fundraising expedition into the northern states and subsequently across the Atlantic into Britain and Europe, where their music landed with resounding impact with royals and average citizens alike. Here and abroad the group refused to play for segregated audiences. And as their popularity rose, “fame did not make them cautious,” Ward writes. “In fact, it emboldened them. With increasing vehemence and eloquence, they denounced racism wherever they encountered it.”

Consider these powerful passages from Ward’s Preface:

Consider these powerful passages from Ward’s Preface:

“In October 1871, a troupe of young former slaves and freedmen set out from Nashville, Tennessee, under the direction of a white Northern missionary named George Leonard White. Their purpose was to raise enough money to rescue their school, Fisk University, from bankruptcy. For months, they journeyed through Ohio and Pennsylvania and into New York, singing the secret soul music of their ancestors. Expelled from hotels, their clothes running to rags, they struggled in obscurity, performing at small-town churches, halls, street corners, and train stations. But as word of their extraordinary artistry spread, they began one of the most remarkable trajectories in American history: from whipping post and auction block to concert hall and throne room.

“For most white Americans, the music of the Jubilee Singers was their first lesson in African American culture, the promise of emancipation, and the meaning of the Civil War. The Jubilees introduced vast white audiences to slave hymns; the first authentic African American music most whites had ever heard. In a tradition that continues to this day, they established the spiritual as a permanent part of the universal liturgy, a staple of religious expression. In their wake has rolled wave after wave of African American song.

“Over the years, however, many came to regard the Jubilee Singers as accommodationists: the meek and pious agents of Northern white missionaries. But what astonished me as I read through their diaries and clippings were their militancy and fierce autonomy. After writing this book, I have come to believe they deserve to be included with Douglass and Du Bois and Martin Luther King, Jr., in the pantheon of great African American champions of civil rights; that the impression they made, their uncompromising artistry and faith, the dignity and outspoken courage they showed as representatives of American freedmen were like a constellation in the dark midnight from which they rose.”

We publish Trotter’s text in its original form, with his punctuation and spellings intact.

***

MUSIC

AND SOME

HIGHLY MUSICAL PEOPLE:

CONTAINING BRIEF CHAPTERS ON

- A DESCRIPTION OF MUSIC. II.THE MUSIC OF NATURE.

III. A GLANCE AT THE HISTORY OF MUSIC.

IV. THE POWER, BEAUTY, AND

USES OF MUSIC.

FOLLOWING WHICH ARE GIVEN SKETCHES OF THE LIVES OF

REMARKABLE MUSICIANS OF THE COLORED RACE.

With Portraits,

AND AN APPENDIX CONTAINING COPIES OF MUSIC

COMPOSED BY COLORED MEN.

BY

JAMES M. TROTTER.

“A man should hear a little music, read a little poetry, and see a fine picture, every day of his life, in order that worldly cares may not obliterate the sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul.”—Goethe.

“‘Tis thine to merit, mine to record.”—Homer.

FIFTH THOUSAND.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM.

1881.

Copyright, 1878,

By JAMES M. TROTTER.

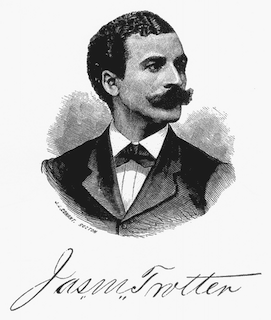

About this book: James Monroe Trotter (1842-1892) was born into slavery in Mississippi. His mother escaped with Trotter and his brother via the Underground Railroad, and they settled in Cincinnati, where Trotter became a teacher. He moved to Boston and fought in the Civil War, becoming the first African-American to achieve the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Union Army. He later became the first African-American to be employed by the U.S. Post Office, but resigned in protest when discrimination prevented his promotion. His Music and Some Highly Musical People, written in 1878, is said to be the first comprehensive study of music written in the United States. In 1887, President Cleveland appointed Trotter to the office of Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, succeeding the great African-American statesman Frederick Douglass in what was then the highest government position to be attained by an African-American. (Source: Wikipedia.)

PREFACE.

The purposes of this volume will be so very apparent to even the most casual observer, as to render an extended explanation here unnecessary. The author will therefore only say, that he has endeavored faithfully to perform what he was convinced was a much-needed service, not so much, perhaps, to the cause of music itself, as to some of its noblest devotees and the race to which the latter belong.

The inseparable relationship existing between music and its worthy exponents gives, it is believed, full showing of propriety to the course hereinafter pursued—that of mingling the praises of both. But, in truth, there was little need to speak in praise of music. Its tones of melody and harmony require only to be heard in order to awaken in the breast emotions the most delightful. And yet who can speak at all of an agency so charming in other than words of warmest praise? Again: if music be a thing of such consummate beauty, what else can be done but to tender an offering of praise, and even of gratitude, to those, who, by the invention of most pleasing combinations of tones, melodies, and harmonies, or by great skill in vocal or instrumental performance, so signally help us to the fullest understanding and enjoyment of it?

As will be seen by a reference to the introductory chapters, in which the subject of music is separately considered, an attempt has been made not only to form by them a proper4 setting for the personal sketches that follow, but also to render the book entertaining to lovers of the art in general.

While grouping, as has here been done, the musical celebrities of a single race; while gathering from near and far these many fragments of musical history, and recording them in one book,—the writer yet earnestly disavows all motives of a distinctively clannish nature. But the haze of complexional prejudice has so much obscured the vision of many persons, that they cannot see (at least, there are many who affect not to see) that musical faculties, and power for their artistic development, are not in the exclusive possession of the fairer-skinned race, but are alike the beneficent gifts of the Creator to all his children. Besides, there are some well-meaning persons who have formed, for lack of the information which is here afforded, erroneous and unfavorable estimates of the art-capabilities of the colored race. In the hope, then, of contributing to the formation of a more just opinion, of inducing a cheerful admission of its existence, and of aiding to establish between both races relations of mutual respect and good feeling; of inspiring the people most concerned (if that be necessary) with a greater pride in their own achievements, and confidence in their own resources, as a basis for other and even greater acquirements, as a landmark, a partial guide, for a future and better chronicler; and, finally, as a sincere tribute to the winning power, the noble beauty, of music, a contemplation of whose own divine harmony should ever serve to promote harmony between man and man,—with these purposes in view, this humble volume is hopefully issued.

THE AUTHOR.

XIX.

THE FAMOUS JUBILEE SINGERS

OF

FISK UNIVERSITY.

| “The air he chose was wild and sad:… Now one shrill voice the notes prolong; Now a wild chorus swells the song. Oft have I listened and stood still As it came softened up the hill.” Sir Walter Scott. |

“If, in brief, we might give a faint idea of what it is utterly impossible to depict, we would adopt three words,—soft, sweet, simple.”

“The Jubilee Singers:” London Rock.

THE dark cloud of human slavery, which for over two hundred weary years had hung, incubus-like, over the American nation, had happily passed away. The bright sunshine of emancipation’s glorious day shone over a race at last providentially rescued from the worst fate recorded in all the world’s dark history. Up out of the house of bondage, where had reigned the most terrible wrongs, where had been stifled the higher aspirations of manhood, where genius had been crushed, nay, more, where attempts had been made to annihilate even all human instincts,—from this accursing region, this charnel-house of human woe, came the latter-day children of Israel, the American freedmen.

How much like the ancient story was their history! The American nation, Pharaoh-like, had long and steadily refused to obey the voice of Him who said, between every returning plague, “Let my people go;” and, after long waiting, he sent the avenging scourge of civil strife to compel obedience. The great war of the Rebellion (it should be called the war of retribution), with its stream of human blood, became the Red Sea through which these long-suffering ones, with aching, trembling limbs, with hearts possessed half with fear and half with hope hitherto so long deferred, passed into the “promised land” of blessed liberty.

Slavery, then, ended, the first duty was to repair as far as possible its immense devastations made upon the minds of those who had so long been its victims. The freedmen were to be educated, and fitted for the enjoyment of their new positions.

In this place I may not do more than merely touch upon the beneficent work of those noble men and women who at the close of the late war quickly sped to the South, and there, as teachers of the freedmen, suffered the greatest hardships, and risked imminent death from the hands of those who opposed the new order of things; nay, many of them actually met violent death while carrying through that long-benighted land the torch of learning. Not now can we more than half appreciate the grandeur of their Heaven-inspired work. In after-times the historian, the orator, and the poet shall find in their heroic deeds themes for the most elevated discourse, while the then generally cultured survivors of a race for whose elevation these true-hearted educators did so much will gratefully hallow their memories.

‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,’ Fisk University Jubilee Quartet (John Wesley Work II, Noah Walker Ryder, James Andrews Myers, Alfred Garfield King). Single issued on Victor 16453, recorded in Camden, NJ, December 1, 1909. This is the first recording of ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.’

Among the organizations (I cannot mention individual names: their number is too great) that early sought to build up the waste places of the South, and to carry there a higher religion and a much-needed education, was the American Missionary Association. This society has led all others in this greatly benevolent work, having reared no less than seven colleges and normal schools in various centres of the South. The work of education to be done there is vast, certainly; but what a very flood of light will these institutions throw over that land so long involved in moral and intellectual darkness!

The principal one of these schools is Fisk University, located at Nashville, Tenn.; the mention of which brings us to the immediate consideration of the famous “Jubilee Singers,” and to perhaps the most picturesque achievement in all our history since the war. Indeed, I do not believe that anywhere in the history of the world can there be found an achievement like that made by these singers; for the institution just named, which has cost thus far nearly a hundred thousand dollars, has been built by the money which these former bond-people have earned since 1871 in an American and European campaign of song.

But what was the germ from which grew this remarkable concert-tour, and its splendid sequence, the noble Fisk University?

Shortly after the close of the war, a number of philanthropic persons from the North gathered into an old government-building that had been used for storage purposes, a number of freed children and some grown persons living in and near Nashville, and formed a school. This school, at first under the direction of Professor Ogden, was ere long taken under the care of the American Missionary Association. The number of pupils rapidly increasing, it was soon found that better facilities for instruction were required. It was therefore decided to take steps to erect a better, a more permanent building than the one then occupied. Just how this was to be done, was, for a while, quite a knotty problem with this enterprising little band of teachers. Its solution was attempted finally by one of their number, Mr. George L. White, in this wise: He had often been struck with the charming melody of the “slave songs” that he had heard sung by the children of the school; had, moreover, been the director of several concerts given by them with much musical and financial success at Nashville and vicinity. Believing that these songs, so peculiarly beautiful and heart-touching, sung as they were by these scholars with such naturalness of manner and sweetness of voice, would fall with delightful novelty upon Northern ears, Mr. White conceived the idea of taking a company of the students on a concert-tour over the country, in order to thus obtain sufficient funds to build a college. This was a bold idea, seemingly visionary; but the sequel proved that it was a most practical one.

All arrangements were completed; and the Jubilee Singers, as they were called, left Nashville in the fall of 1871 for a concert-tour of the Northern States, to accomplish the worthy object just mentioned. Professor White, who was an educated and skilful musician, accompanied them as musical director. Mr. Theodore F. Seward, also of fine musical ability, was, after a while, associated in like capacity with the singers. The following are the names of those who at one time and another, since the date of organization, have been members of the Jubilee choir:—

| Miss ELLA SHEPARD, Pianist. | |

| Mr. THOMAS RUTLING, Mr. H. ALEXANDER, Mr. F.J. LOUDIN, Mr. G.H. OUSLEY, Mr. BENJAMIN M. HOLMES, Mr. ISAAC P. DICKERSON, Mr. GREENE EVANS, Mr. EDMUND WATKINS, |

Miss MAGGIE PORTER, Miss JENNIE JACKSON, Miss GEORGIE GORDON, Miss MAGGIE CARNES, Miss JULIA JACKSON, Miss ELIZA WALKER, Miss MINNIE TATE, Miss JOSEPHINE MOORE, |

| Miss MABEL LEWIS, and Miss A.W. ROBINSON. | |

This list might well be called the Roll of Honor.

I have not space to follow in detail this ambitious band of singers in their remarkable career throughout this country and in Great Britain. The wonderful story of their journey of song is fully and graphically told in a book (which I advise all to read) written by Mr. G.D. Pike, and published in 1873 (Ed. Note: The Jubilee Singers and Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars, available to read free online at Smithsonian Libraries.) A brief survey of this journey must here suffice.

The songs they sang were generally of a religious character,—”slave spirituals,”—and such as have been sung by the American bondmen in the cruel days of the past. These had originated with the slave; had sprung spontaneously, so to speak, from souls naturally musical; and formed, as one eminent writer puts it, “the only native American music.”

‘I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray,’ Fisk Jubilee Quartet (John Wesley Work II, Noah Walker Ryder, James Andrews Myers, Alfred Garfield King), released 1909, reissued on the Document collection, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, In Chronological Order, Volume 1 (1909-1911)

The strange, weird melody of these songs, which burst upon the Northern States, and parts of Europe, as a revelation in vocal music, as a music most thrillingly sweet and soul-touching, sprang then, strange to say, from a state of slavery; and the habitually minor character of its tones may well be ascribed to the depression of feeling, the anguish, that must ever fill the hearts of those who are forced to lead a life so fraught with woe. This is clearly exemplified, and the sad story of this musical race is comprehensively told, in Ps. cxxxvii.:—

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

“We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

“For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion.

“How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?”

And yet, ever patient, ever hopeful of final deliverance, they did sing on and on, until at last the joyful day of freedom dawned upon them.

To render these songs essentially as they had been rendered in slave-land came the Jubilee Singers. They visited most of the cities and large towns of the North, everywhere drawing large and often overwhelming audiences, creating an enthusiasm among the people rarely ever before equalled. The cultured and the uncultured were alike charmed and melted to tears as they listened with a new enthusiasm to what was a wonderfully new exhibition of the greatness of song-power. Many persons, it is true, were at first attracted to the concert-hall by motives of mere curiosity, hardly believing, as they went, that there could be much to enjoy. These, however, once under the influence of the singers, soon found themselves yielding fully to the enchanting beauty of the music; and they would come away saying the half had not been told. The musical critics, like all others in the audiences, were so lost in admiration, that they forgot to criticise; and, after recovering from what seemed a trance of delight, they could only say that this “music of the heart” was beyond the touch of criticism.

‘Ezekiel Saw De Wheel,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Every Time I Feel the Spirit, In Chronological Order, Volume 3 (1924-1940). Personnel on this track: James A. Myers, Carl Barbour (tenors); Mrs. James A. Meyers (alto); Horatio O’Bannon (baritne); Ludie David Collins (bass).

I have spoken of the origin and the character of these songs. Those who so charmingly interpreted them deserve most particular notice. The rendering of the Jubilee Singers, it is true, was not always strictly in accordance with artistic forms. The songs did not require this; for they possessed in themselves a peculiar power, a plaintive, emotional beauty, and other characteristics which seemed entirely independent of artistic embellishment. These characteristics were, with a most refreshing originality, naturalness, and soulfulness of voice and method, fully developed by the singers, who sang with all their might, yet with most pleasing sweetness of tone.

But, as regards the judgment passed upon this “Jubilee melody” from a high musical stand-point, I quote from a very good authority; viz., Theo. F. Seward of Orange, N.J.:—

“It is certain that the critic stands completely disarmed in their presence. He must not only recognize their immense power over audiences which include many people of the highest culture, but, if he be not entirely incased in prejudice, he must yield a tribute of admiration on his own part, and acknowledge that these songs touch a chord which the most consummate art fails to reach. Something of this result is doubtless due to the singers as well as to their melodies. The excellent rendering of the Jubilee Band is made more effective, and the interest is intensified, by the comparison of their former state of slavery and degradation with the present prospects and hopes of their race, which crowd upon every listener’s mind during the singing of their songs; yet the power is chiefly in the songs themselves.”

‘In Bright Mansions Above,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, In Chronological Order, Volume 1 (1909-1911). Personnel: John Wesley Work II (1st tenor); James Andrews Meyers (2nd tenor); Alfred Garfield King (1st bass); Noah Walker Ryder (2nd bass).

It would not do, of course, to assume that to the almost matchless beauty of the songs and their rendering was due alone the intense interest that centred in these singers. They were on a noble mission. They sang to build up education in the blighted land in which they themselves and millions more had so long drearily plodded in ignorance; and it was a most striking and yet pleasing exhibition of poetic justice, when many of those who really, in a certain sense, had been parties to their enslavement, were forced to pay tribute to the signs of genius found in this native music, and to contribute money for the cause represented by these delightful musicians.

But I must not give only my own opinion of these singers, as I am supposed to be a partial witness. Many, many others, among whom are the most talented and cultured of this country and England, have spoken of them in terms the most laudatory. Some of these shall now more than confirm my words of praise.

The Rev. Theodore L. Cuyler of Brooklyn, writing in January, 1872, to “The New-York Tribune,” thus spoke of them:—

“When the Rev. Mr. Chalmers (the younger) visited this country as the delegate of the Scotch Presbyterian General Assembly, he went home and reported to his countrymen that he had ‘found the ideal church in America: it was made up of Methodist praying, Presbyterian preaching, and Southern negro-singing.’ The Scotchman would have been confirmed in his opinion if he had been in Lafayette-avenue Church last night, and heard the Jubilee Singers,—a company of colored students, male and female, from Fisk University of Freedmen, Nashville, Tenn. In Mr. Beecher’s church they delighted a vast throng of auditors, and another equally packed audience greeted them last evening.

‘Golden Slippers,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Every Time I Feel the Spirit, Volume 3 (1924-1940). Personnel: W. Nathaniel Dickerson, William Collier, Herbert Rutherford (tenor); Arthur Bostic, Oswald Lampkins (baritone); Carl Weems (bass); Mrs. James A. Myers (alto & vocal director).

“I never saw a cultivated Brooklyn assemblage so moved and melted under the magnetism of music before. The wild melodies of these emancipated slaves touched the fount of tears, and gray-haired men wept like children….

“The harmony of these children of nature, and their musical execution, were beyond the reach of art. Their wonderful skill was put to the severest test when they attempted ‘Home, Sweet Home,’ before auditors who had heard these same household words from the lips of Jenny Lind and Parepa; yet these emancipated bondwomen, now that they knew what the word ‘home’ signifies, rendered that dear old song with a power and pathos never surpassed.

“Allow me to bespeak through your journal … a universal welcome through the North for these living representatives of the only true native school of American music. We have long enough had its coarse caricature in corked faces: our people can now listen to the genuine soul-music of the slave-cabins before the Lord led his ‘children out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.'”

The welcome thus eloquently bespoken for the singers was enthusiastically extended to them all over the North. The journals of the day fairly teemed with praises of them; and often, in the larger cities, hundreds of persons were turned away from the concert-hall, unable to obtain admittance, so great was the rush.

After a while they visited England, where they sang before the Queen and others of the nobility, everywhere repeating the triumphs that had been theirs in this country. In fact, it was proved that their power as singers held sway wherever they sang; wherever was found a soul in unison with melodious sound, a heart capable of human emotion. It was not so much the words of their songs—these, it is true, were not without merit in a religious sense—as the strangely pathetic and delightful melody of their music, and the freshness and heartiness of the rendering, that gave them their greatest charm. This has since been most pointedly demonstrated in Holland and Switzerland, where these singers have drawn crowded and delighted audiences that neither speak nor understand a word of English: such is the beautiful, far-reaching power of this, in the truest sense, “music of the heart.”

‘The Great Camp Meeting,/ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Roll Jordan Roll, In Chronological Order, Volume 2 (1915-1920). Personnel: John Work II, James A. Meyers (tenors); J. Everett Harris (baritone); Lemuel L. Foster (bass). Note: the album cover shown in the YouTube video above shows the wrong volume in which ‘The Great Camp Meeting” is found.

I now present a few of the many tributes of admiration which their performances drew from cultured English people. Thus spoke Mr. Colin Brown, Ewing Lecturer on Music, Andersonian University, Glasgow:—

“As to the manner of their singing, it must be heard before it can be realized. Like the Swedish melodies of Jenny Lind, it gives a new musical idea. It has been well remarked, that in some respects it disarms criticism; in others it may be truly said that it almost defies it. It was beautifully described by a simple Highland girl: ‘It filled my whole heart.’

“Such singing (in which the artistic is lost in the natural) can only be the result of the most careful training. The richness and purity of tone both in melody and harmony, the contrast of light and shade, the varieties and grandeur in expression, and the exquisite refinement of the piano as contrasted with the power of the forte, fill us with delight, and at the same time make us feel how strange it is that these unpretending singers should come over here to teach us what is the true refinement of music; make us feel its moral and religious power.”

Others spoke as follows:—

“I never so enjoyed music.”—Rev. C.H. Spurgeon.

“They have beautiful voices.”—London Graphic.

“Their voices are clear, rich, and highly cultivated.”—London Daily News.

“This troupe sing with a pathos, a harmony, and an expression, which are quite touching.”—London Journal.

“There is something inexpressibly touching in their wonderfully sweet, round, bell voices.”—Rev. George MacDonald.

Mr. Gladstone, while prime-minister of England, honored them with a complimentary breakfast, and listened to their songs, as Newman Hall writes, “with rapt, enthusiastic attention, saying, ‘Isn’t it wonderful? I never heard any thing like it.'”

“We never saw an audience more riveted, nor a more thorough heart entertainment. Men of hoary hairs, as well as those younger in the assembly, were moved even to tears as they listened with rapt attention to some of the identical slave-songs which these emancipated ones rendered with a power and pathos perfectly indescribable.”—London Rock.

I might now, if it were necessary, fill many pages with the comments made upon these charming singers by the American press both before and after their trip to England; but these would only be repetitions of the laudatory notices just given. The following is quoted because it is descriptive of the improvement made by the singers. Said “The Boston Journal,”—

“The Jubilee Singers.—The students of Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn., whose sweet voices made such a popularity for the Jubilee Singers in this city two or three years ago, and won royal favor on the other side of the Atlantic, gave their first concert since their return at Tremont Temple last evening. The audience numbered some two thousand persons, and manifested an enthusiasm seldom witnessed at a concert in this city. From the initial to the finale of the programme the singers were applauded and encored, and now and then the enthusiasm broke forth in the interludes. So many thousands have listened with delight to the full, rich voices of the ‘Jubilees,’ and the sweet undertone which disarms criticism while it charms the popular ear, that it is needless to speak of them at length. The simple purity of the rendering of the Lord’s Prayer, which initiated the programme, gave evidence that they had lost none of their natural grace and simplicity of expression by their tour across the water; and this was confirmed by the peculiar and plaintive melodies of the South-land in the days of slavery, which made up the major part of the programme. A few selections of more artistic composition were introduced, for the purpose of demonstrating, as they did most fully, that the students have been educated to an appreciation of the higher grades of vocalization. The great charm of these singers will, however, remain in the reproduction of the melodies of an era that has gone, happily never to return,—melodies which were the natural expression of the fancies and sympathies of an emotional race, and which no musical culture or refinement can ever render with the sweet simplicity and charming grace that flow from the lips of those to whom they are the native music.”

“In the summer of 1874 they returned to Nashville, having given two seasons of concerts in this country, and one in Great Britain. The best evidence of the appreciative and enthusiastic welcome given them in both countries is the fact that the net result for Fisk University was over $90,000.” The “problem” of the little band of faithful teachers had been nobly, gloriously solved. The old government-building in which they began their labors was soon discarded. To-day, on a beautiful, commanding site of twenty-five acres, with all the appliances of the best modern colleges, stands a noble building, forever dedicated to learning and to Christianity.

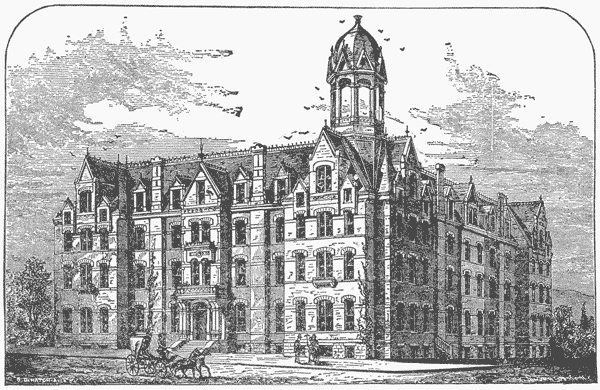

Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn.

Since the events whose record is just closed, it has been determined by the faculty of Fisk University to raise by other concert tours $100,000 as an endowment fund. At the present writing (June, 1877) the Jubilee Singers are making a tour of the Continent. They are now in Holland. Thus far their success continues unabated; and undoubtedly they will succeed in amply endowing the institution which, in a manner so praiseworthy and remarkable, they have erected. The following extract from a letter affords a pleasant glimpse at the European life of the singers:—

… “I will tell you something of our summer’s experience. The company had passed through a hard year’s work, and were greatly in need of rest. A charming country-seat was rented in the suburbs of Geneva at a very reasonable rate, and the months of July and August were spent there with great benefit to all. The citizens were evidently astonished at this introduction of a new shade of humanity; and the singers seldom passed along the streets without hearing some remark about ‘les nègres,’ or ‘les noirs.’ But they were invariably treated with the greatest respect, and, in fact, were never once annoyed by a rabble in the streets, as they frequently are elsewhere, gathering around with a rude and impertinent curiosity.

“Among other pleasant experiences, there was an afternoon spent with Père Hyacinthe. We found him very genial and agreeable, and his American wife no less so. He speaks no English at all, but Madame acted as interpreter; and there was none of the stiffness or awkwardness that might have been expected under the circumstances.

‘Blessed Assurance,’ the present-day Fisk Jubilee Singers with guest vocalist CeCe Winans, from Celebrating Fisk! The 150th Anniversary Album (2020)

“… The most notable event of our stay at Geneva was a concert given, just before leaving, in the Salle de la Réformation. It had been a question of much interest, as to whether the slave-songs would retain any thing of their power where the words were not understood. The result was a new triumph for those mysterious melodies, showing that the language of nature is universal, and that emotion is capable of expressing itself without the intervention of words. The hall was packed to its utmost capacity, and the enthusiasm at fever-heat. When asked how they could enjoy the songs so much when they knew nothing of the sentiment that was conveyed, the reply was, ‘We cannot understand them; but we can feel them.’ Père Hyacinthe presided at the concert as chairman, and evidently enjoyed it as keenly as the rest of the vast audience.”

And now to discriminate; for the writer, while disclaiming all censorious or pretentious aim, yet, for reasons which may be readily understood and fully appreciated by the reader, intends this volume to inculcate the lessons of advancement by always attempting to honestly distinguish between that which is progressive in music and that which is the reverse. Have, then, these famous Jubilee Singers, who everywhere thrilled the hearts of their hearers, and whose charming melody of voice, and style of rendition, “disarmed the critic,”—have they established by all this a model for the present and the future? In some respects they have; in others they have not. And is there to be no aim beyond the singing of “Jubilee songs”? Professors White and Seward and all these talented singers will say, I am quite sure, that there is to be a higher aim. The songs they sang were for the present, forming a delightful novelty, and serving a noble purpose. Still it must be sadly remembered that these Jubilee songs sprang from a former life of enforced degradation; and that, notwithstanding their great beauty of melody, and occasional words of elevated religious character, there was often in both melody and words what forcibly reminded the hearer of the unfortunate state just mentioned; and to the cultured, sensitive members of the race represented, these reminders were always of the most painful nature. And yet such persons could not have the heart to utter words of discouragement to an enterprise having an object so noble. They, like all others, could not but enjoy the rich melody and harmony of the wonderful Jubilee voices. They, too, often listened spell-bound; and when inclined, as at times they were, to murmur, the inspiriting voice of hope was heard bidding them to turn from a view of the dark and receding past to that of a rapidly-dawning day, whose coming should bring for these singers, and all others of their race, increase of opportunities, and therefore increase of culture.

‘Steal Away to Jesus,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Roll Jordan Roll, In Chronological Order, Volume 2 (1915-1920). Personnel: John Work II, James A. Meyers (tenors); J. Everett Harris (baritone); Lemuel L. Foster (bass).

On the foregoing pages but little has been said of the secular songs with which at times the troupe indulged their audiences. Even in music of this kind they were exceedingly pleasing; and it is very gratifying to reflect that the members of the company constantly aimed to obtain a scientific knowledge of general music. No fears need be entertained that the students of Fisk University will ever lack for instruction in music of the highest order, as ample provision is there made for the same. Of course the model of slave “spirituals” will in a short while give place to such music as befits the new order of things. The students themselves will wish to aim higher, as the spirit of true progress will demand it. Nevertheless, some of the characteristics displayed by the great Jubilee choir it will be well for them to ever retain, and for all other singers to imitate: I mean the heartiness, the soulfulness, of their style of rendition. Indeed, in their striking exhibitions of these latter qualities, I think they may justly claim the honor of standing quite peerless and alone, and of having presented a model for the present and the future,—a model founded on that power of the singer, which enables him to melt, to stir to its innermost recesses, the human heart; that power that enables him to sing as one inspired.

And here let me conclude by venturing a brief prediction. My mind goes a few years into the future. I attend a concert given by students or by graduates of Fisk University; I listen to music of the most classical order rendered in a manner that would satisfy the most exacting critic of the art; and at the same time I am pleasantly reminded of the famous “Jubilee Singers” of days in the past by the peculiarly thrilling sweetness of voice, and the charming simplicity and soulfulness of manner, that distinguish and add to the beauty of the rendering.

***

Editor’s Note: And what has it amounted to, the Jubilee’s century and a half-plus of music making? Noting that the popularity of spirituals rises and falls according to the state of race relations at any given time in our history, Ward writes, “the singers’ contribution to American music is as permanent as it is incalculable. The Jubilees helped to rescue American music from its obsequious bondage to the often insipid, secondhand trappings of the English and European tradition. They contributed to the creation of a music so all-embracing as to accommodate not only African American strains but Latin, Asian, Jewish, and Native American influences as well. (Nashville’s own reputation as the ‘Music City’ began not with the Grand Ole Opry but with the Jubilee Singers.) In 1895, the Czech composer Anton Dvorák, then head of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, declared that if America ever intended to develop its own music, it need look no further than the African American songs to which the Jubilee Singers had provided the gateway.

“You can hear an echo of the Jubilees in the works of Gershwin, Copland, and Ellington. It infuses the chords and cadences of jazz, even down to the disposition of instruments and the improvisational matrix of the classic jazz quartet. The Jubilees haunt the arrangements of Fletcher Henderson and Benny Goodman; the muted lyricism of early Miles Davis; Charles Mingus’s “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting”; the riffs of Thelonious Monk, Mose Allison, and Jimmy Smith; the call and response of Little Richard, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston.”

‘In the Great Getting Up Mawnin’,’ Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Document collection, Roll Jordan Roll, In Chronological Order, Volume 2 (1915-1920). Personnel: John Work II, James A. Meyers (tenors); J. Everett Harris (baritone); Lemuel L. Foster (bass).

Ward concludes his essential biography with an anecdote dating to August 1897, when Mark Twain, “now a nearly impoverished old man of sixty-one, grieving on the first anniversary of the death of his beloved daughter Susy,” on a visit to Lucerne, Switzerland, visited a beer garden where the Jubilees were performing. Amidst Swiss patrons Twain described as sitting impassively “at round tables with their beer mugs in front of them…an indifferent, unposted and disheartened audience,” Twain found himself renewed by the Jubilees’ soulful outpourings: “There rose and swelled out above those common earthly sounds one of those rich chords the secret of whose make only the Jubilees possess, and a spell fell upon that house. It was fine to see the faces light up with the pleased wonder and surprise of it. No one was indifferent any more…

“Arduous and painstaking has not diminished or artificialized their music, but on the contrary—to my surprise—has mightily reinforced its eloquence and beauty. Away back in the beginning—to my mind—their music made all other vocal music cheap; and that early notion is emphasized now. It is utterly beautiful, to me; and it moves me infinitely more than any other music can.”

In the Jubilees and their songs, Twain concluded, “American has produced the perfectest flower of the ages.”

James M. Trotter’s Music and Some Highly Musical People is available free in e-book form at Project Gutenberg, from which this chapter is excerpted.

Fisk Jubilee Singers, 2023