Celia Johnson as Jenny, Ralph Richardson as Irish clergyman Martin Gregory in The Holly & The Ivy

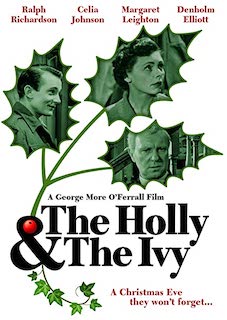

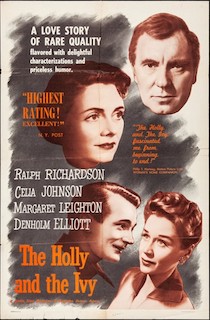

For decades, fans of the small holiday gem that is 1952’s The Holly & The Ivy, directed by George More O’Ferrall from a script by the film’s producer, Anatole de Grunwald, and playwright Wynard Browne (from his like-titled 1950 stage play) and starring a cast comprised of top-tier British actors of the day, led by Ralph Richardson and Margaret Leighton had no recourse but to wait for the British film’s seasonal TV airings. A VHS release in the ’80s came and went in record time. Until very recently, maybe three years ago, Region 1 DVD versions of the movie were non-existent. To the rescue came King Lorber (formerly Kino International) and the French film production/distribution company StudioCanal issued the long-awaited Region 1 version complete with informed, insightful audio commentary by film historian Jeremy Arnold-an outstanding package for fans and film buffs alike. In the absence of a home video version of the film, the Turner Classic Movies channel often programmed The Holly & The Ivy during the holiday season, but once the New Year rang in it disappeared until the next Yuletide rolled around. The drought has now ended.

Sir Ralph is brilliant in his role as a recently widowed Irish clergyman Martin Gregory, whose devotion to his parishioners blinds him to the needs of his own family, And those needs are myriad and serious–the growing alcoholism of estranged daughter Margaret (Margaret Leighton), a London-based magazine writer (and atheist) who has been hiding a dark secret: that an affair with a WWII soldier left her an unwed mother whose four-year-old son recently died of meningitis; son Michael (young Denholm Elliott in a typically understated but commanding performance well before he became one of the movies’ most persuasive bad guys), rebelling against his father’s religion and plans to send him to university when the son completes service in the Royal Artillery; daughter Jenny (Celia Johnson), caretaker for her father but desiring to marry her beau, David, an engineer, and join him when he leaves for a five-year job in South America but stuck at home with dad unless her sister or one of her aunts will become his  caretakers. To say that things are at loggerheads is an understatement, and the ensuing tensions, along with a few fireworks, play out with varying degrees of intensity and introspection as Christmas approaches. The Holly & The Ivy is not a Christmas movie per se, but rather a movie in which Christmas becomes a beckoning presence in subtle ways–the soft voices of a choir singing low in the background at various points, and especially the sound of church bells pealing in the distance every so often as a nuanced reminder of the approaching Yule, and of what it means. The bells peal ever louder as family issues are resolved in a perfectly heartwarming way, absent all sentimentality, on Christmas Day, leading to an exquisite closing shot of the principals together in church, as moving in its depiction of familial love as its brevity is profound.

caretakers. To say that things are at loggerheads is an understatement, and the ensuing tensions, along with a few fireworks, play out with varying degrees of intensity and introspection as Christmas approaches. The Holly & The Ivy is not a Christmas movie per se, but rather a movie in which Christmas becomes a beckoning presence in subtle ways–the soft voices of a choir singing low in the background at various points, and especially the sound of church bells pealing in the distance every so often as a nuanced reminder of the approaching Yule, and of what it means. The bells peal ever louder as family issues are resolved in a perfectly heartwarming way, absent all sentimentality, on Christmas Day, leading to an exquisite closing shot of the principals together in church, as moving in its depiction of familial love as its brevity is profound.

In 2008, long before the DVD was available in this country, Jeremy Arnold penned a summary essay about The Holly & The Ivy that touched on themes he developed further in his DVD audio commentary. Here’s what he had to say about this essential holiday movie. –David McGee

***

On The Holly & The Ivy: A Slight but Gripping Tale

By Jeremy Arnold

Published at TCM.com, 10-07-08

The Holly and The Ivy (1952) takes one of the most common “Christmas movie” storylines–a dysfunctional family reuniting over the holidays–and applies it to rural England circa 1948. The result is a small gem that shows off a fine ensemble of prominent British actors of the era. Chief among them is Ralph Richardson, who plays a widowed country vicar named Martin Gregory living with his grown daughter, Jenny (Celia Johnson). Martin is a kind-hearted man but consumed with his church life to such an extent that he cannot sense that Jenny yearns to leave this small town and go off and marry her boyfriend (John Gregson); instead she stays out of a self-sacrificial sense of duty to look after her father, and hasn’t even told him that she has a boyfriend. Jenny’s sister Margaret (Margaret Leighton) and brother Michael (Denholm Elliott) arrive from London and an Army training camp, respectively, but each has his or her own issues with their father–and they assume that he wouldn’t understand their troubles, or worse, that he would judge them according to a strict religiosity. There’s also a cousin (Hugh Williams) on hand, as well as two spinster aunts who supply light comic relief (Margaret Halstan and Maureen Delany.

As the story develops, the vicar gradually uncovers the turmoil going on within his family, and things start coming out into the open. Richardson delivers a beautifully controlled performance, and his interplay with the other actors builds an intensity that makes this slight tale feel gripping. The tale unfolds almost entirely over Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, and the snowy stillness of the holidays, along with passing carolers and occasional church bells, lend a distinct holiday feel that enhances the sense of place and the family drama. More than many films, The Holly and The Ivy captures the unique experience of adult siblings–who grew up together and shared strong bonds in childhood–now unsure of what is really happening in each other’s lives and struggling to reconnect during the one time of year, Christmas, when they are thrown together again.

A short interview with Professor Mark Connelly commenting on The Holly & The ivy. The Professors is the author of the definitive Christmas at the Movies.

Producer Anatole de Grunwald, who was born in Russia but worked in Britain, wrote the screenplay himself, adapting a 1950 play by Wynyard Browne, who had based it on his own family. To direct, Grunwald hired George More O’Ferrall, a pioneer of British television who directed only a few feature films. The picture was financed and distributed by British Lion, in which the mogul Alexander Korda held a controlling interest.

The cast rehearsed for three weeks on the finished sets, then shot the film in fourteen days, in sequence. This greatly helped the actors inhabit their roles and build steadily toward the story’s emotional final act, in which Richardson dominates. One of England’s great 20th-century stage performers, he’d recently been nominated for an Academy Award for his supporting turn in The Heiress (1949), and he would be nominated again, posthumously, for Greystoke (1984). In the interim, he appeared in such films as Richard III (1955), Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965), as well as countless works for the stage.

Celia Johnson did not make many movies–only around a dozen in all–with the bulk of her career dominated by the theater. Still, she acted in several famous British films, including In Which We Serve (1942), This Happy Breed (1944), The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969), and, most famously, Brief Encounter (1945), for which she was Oscar-nominated. Her role in The Holly and The Ivy, in fact, isn’t that different from her character in Brief Encounter; in both, she is in some way bound to one man but drawn to another. In private life, Johnson was married for decades to Peter Fleming, elder brother of James Bond novelist Ian Fleming.

Celia Johnson did not make many movies–only around a dozen in all–with the bulk of her career dominated by the theater. Still, she acted in several famous British films, including In Which We Serve (1942), This Happy Breed (1944), The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969), and, most famously, Brief Encounter (1945), for which she was Oscar-nominated. Her role in The Holly and The Ivy, in fact, isn’t that different from her character in Brief Encounter; in both, she is in some way bound to one man but drawn to another. In private life, Johnson was married for decades to Peter Fleming, elder brother of James Bond novelist Ian Fleming.

Margaret Leighton is perhaps less remembered today, but she did have a thirty-year film career that included an Oscar nomination for The Go-Between (1971). She was also a mainstay of the British stage, acting with Ralph Richardson–who was infatuated with her–in a famous production of Cyrano de Bergerac and then on screen in four films overall (The Holly and the Ivy was the second).

Two of the cast members originated their roles on stage: Margaret Halston, as the ever-complaining Aunt Lydia, and Maureen Delany, who plays the talkative Aunt Bridget.

The Holly and The Ivy caused no great shakes upon its release in the U.S. in 1954 (two years after opening in Britain), though The New York Times called it “literate and deftly played by the cast of fine performers.” It was shot by cinematographer Ted Scaife, who went on to shoot such visually stylish gems as Curse of the Demon (1957), Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959), and Play Dirty (1969). Seen today, the film is a worthy addition to anyone’s annual holiday viewing plans.