Johnny Marks (1909-85), who specialized in Christmas songs, among them ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

You know Dasher and Dancer and Prancer and Vixen… But do you know the real-life tragedy that spurred Robert May to write a poem for his four-year-old daughter that became a cultural and multimedia phenomenon? Rudolph, with his nose so bright, takes flight.

Robert May was a short man, barely five feet in height, born at the turn of the 20th Century. Bullied at school, he was ridiculed and humiliated by other children because he was smaller than other boys of the same age. Even as he grew up, he was often mistaken for someone’s little brother.

After college he found work as a copywriter with Montgomery Ward, the big Chicago mail order house and department store. He married, and in due course his wife presented him with a daughter. Two years later, tragedy struck: his wife Barbara was diagnosed with cancer. Nearly everything he earned went towards paying for her medication and doctor’s bills. Money was short and life was hard.

One evening in early December of 1938, two years after the onset of his wife’s illness, and only days before her death, his four-year-old daughter climbed onto his knee and asked, “Daddy, why isn’t Mummy like everybody else’s mummy?” Such a simple question, asked with childlike curiosity, it was, and it struck a personal chord with Daddy. As a child, Robert was short, petite in frame. He had often posed the question: “Why can’t I be tall, like the other kids?” The stigma attached to those who are different is hard to bear

Robert May with his creation, Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer

Groping for an answer that would give comfort to his daughter, he began to tell her a story. It was about someone else who was different, someone who was ridiculed, humiliated and excluded because he wasn’t like all the others in his circle—a reindeer with a luminous red nose. May’s first name for his beleaguered subject was Rollo; then he changed it to Reginald; and finally settled on Rudolph, which passed the acid test of gaining his daughter’s enthusiastic approval.

Robert told the story in a humorous way, making it up as he went along. His daughter laughed, giggled and clapped her hands as the misfit finally triumphed at the end. She then made him start all over again from the beginning, and thus began what became a nightly bedtime ritual of repeating the story until the little girl fell asleep.

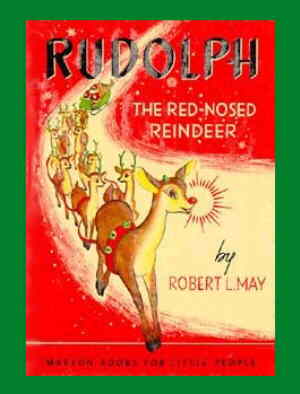

Because he had no money for fancy presents, Robert decided that he would put the story into book form. He had some artistic talent and he created illustrations. This was to be his daughter’s Christmas present: the book of the story that she loved so much.

Because he had no money for fancy presents, Robert decided that he would put the story into book form. He had some artistic talent and he created illustrations. This was to be his daughter’s Christmas present: the book of the story that she loved so much.

On the night before Christmas Eve, he was persuaded to attend his office Christmas party. He took the poem along and showed it to a colleague. The colleague was impressed and insisted Robert read it aloud to the partygoers. Somewhat embarrassed by the attention, he took the small hand-written volume from his pocket and began to read. At first the noisy group listened in laughter and amusement. Soon, though, they fell silent; when he finished, they broke into raucous applause.

Later, feeling quite pleased with himself, he went home, wrapped the book in Christmas wrapping and placed it under the modest Christmas tree. To say that his daughter was thrilled with her present would be an understatement.

When Robert returned to work after the holiday, he was summoned by his department head, who wanted to talk to about Robert’s poem. It seemed word had got around about his reading at the Christmas party. The head of marketing was looking for a promotional tool and wondered if Robert would be interested in having his poem published.

However, Montgomery Ward’s publicity department requested some alterations in the text May’s daughter loved so well. Red noses smacked of drunkenness, he was told, which made them inappropriate for a sweet, gentle, parent-friendly Christmas story. Instead of changing the story, May enlisted the help of illustrator Denver Gillen, a co-worker in the advertising department, to show just how parent-friendly Rudolph could be. With Gillen’s artwork, the original tale passed muster, and the department store chain gave away 2.4 million copies that year. Millions more were given away over the next several years. It eventually was published in hard cover and became an international best seller, making Robert a rich man. With his new-found wealth he bought a big house and moved out of his small, rented apartment and provided handsomely for his growing daughter.

Max Fleischer’s ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ cartoon from 1944, the first animated Rudolph, and the last production of Fleischer’s legendary career.

Rudolph’s story proved so popular that hard covers could not contain it. In 1944 it became an animated sensation when Max Fleischer, in a rare commercial credit following the closure of his studio, produced an animated version of the Rudolph story for The Jam Handy Organization (a Detroit studio) that became a staple of TV holiday fare in the 1950s and early ’60s. Unlike most Rudolph products, it’s fallen out of copyright and is now available on many inexpensive videotapes and DVDs of public domain Christmas shorts. It was the final cartoon production from the man who had produced Popeye, Betty Boop and Koko the Clown cartoons from 1910 into the 1940s.

Gene Autry’s original version of Johnny Marks’s ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,’ 1949.

The ‘Holly Jolly Christmas’ scene, with Sam the Snowman (Burl Ives) leading the singalong, from Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

In 1947, May negotiated ownership of the Rudolph property, which had hitherto been held solely by Montgomery Ward. It was shortly afterward that his brother-in-law, Johnny Marks, turned the poem into a song that was in turn pitched to the reigning western box office champ, Gene Autry. The Singing Cowboy’s original version, released in 1949, sold two million copies; in the years since it has sold more than 150 million copies. (The song had been introduced on radio by Sinatra-like crooner Harry Brannon before Autry’s record was released, making Brannon’s now-forgotten rendition the first commercial version.)

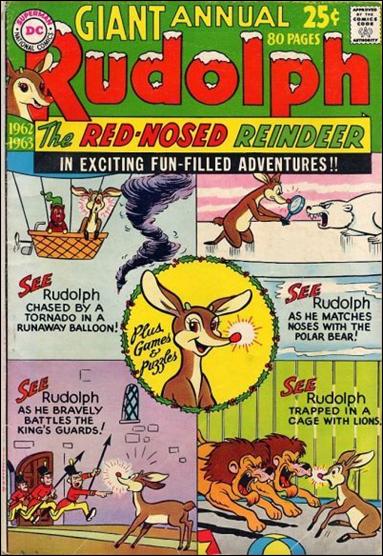

Next came a comic book that recounted Rudolph’s adventures after he’d become an accepted part of Santa Claus’s team. DC Comics published a new issue each December from 1950-62. Most were drawn by Rube Grossman (Peter Panda, Three Mouseketeers). The DC version was revived briefly in 1972 as a tabloid, written and drawn by Sheldon Mayer (Sugar & Spike, The Red Tornado). While the DC version was running, Little Golden Books produced its own version of the story and followed it with Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer Shines Again.

Next came a comic book that recounted Rudolph’s adventures after he’d become an accepted part of Santa Claus’s team. DC Comics published a new issue each December from 1950-62. Most were drawn by Rube Grossman (Peter Panda, Three Mouseketeers). The DC version was revived briefly in 1972 as a tabloid, written and drawn by Sheldon Mayer (Sugar & Spike, The Red Tornado). While the DC version was running, Little Golden Books produced its own version of the story and followed it with Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer Shines Again.

Rankin/Bass Productions (Thundercats, Silverhawks, Frosty the Snowman, Frosty Returns) did the best-known animated version, narrated by Burl Ives as Sam the Snowman, which debuted on NBC on December 6, 1964. Rather than traditional cel animation, Rankin-Bass used a stop-motion technique with puppets, similar to George Pal’s Puppetoons, but which they promoted under the trademarked name “Animagic.” Rudolph’s voice was done by Billie Mae Richards (Bobby in King Kong). Richards reprised her role in a couple of follow-ups, Rudolph’s Shiny New Year (1976) and Rudolph & Frosty’s Christmas in July (1979).

Rudolph’s first feature-length movie was titled, appropriately enough, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer: The Movie, and was released to video October 16, 1998. It boasted a star-studded cast, with voices by Whoopi Goldberg, Bob Newhart and, as Santa, John Goodman. Rudolph was voiced by Kathleen Barr (Dot Matrix in Reboot, various voices in Sonic the Hedgehog and Ranma ½). Barr played Rudolph again in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer & The Island of Misfit Toys, released to video October 30, 2001.

A Johnny Marks lyric promised Rudolph that he would “go down in history.” Who knew?

(Thanks to Don Markstein’s Toonopedia for the multimedia history of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”)