By Jules

‘My leaves gave people shade. My branches gave birds a place to rest.

And each year, I was one of the first trees to blossom.

My flowers let everyone know that spring was coming.’

(Click spread to enlarge)

We will soon mark the 20th anniversary of 9/11. It’s hard to believe. Children’s literature will acknowledge this with more than one book. This month we focus on author-illustrator Sean Rubin’s This Very Tree, released in May, and author Marcie Colleen and illustrator Aaron Becker’s Survivor Tree (Little Brown) now on the shelves.

Sean Rubin’s This Very Tree (Henry Holt, May 2021) is based on, as Sean explains below, research around trauma and its treatment. Dr. Lucy Guarnera (Sean’s wife) taught him, as he notes in the book’s acknowledgments, what it would look like for the survivor tree–the Callery pear tree planted near the Towers in the 1970s, which survived the Towers’ falls–to “experience its trauma and recovery as a human would.”

Opening with an excerpt from E. B. White’s Here Is New York, the book tells the tree’s story of 9/11, and its recovery and rebirth, in a reverent first-person voice. It addresses the day’s tragedy in an age-appropriate way; is paced with a measured and lovely gentleness when the tree, after being found in the rubble, is sent away to heal (“I was grateful to be somewhere quiet”); and is anchored by Sean’s detailed, research-driven illustrations in which color and shadow communicate great emotion. (One of the book’s delightful design details: The book’s typefaces were chosen for their appearance on the cornerstone of the current One World Trade Center.)

Sean visits today to talk about the book, share some process images, and explain why the book never explicitly mentions 9/11 in the narrative itself. I thank him for visiting.

* * *

Jules: I’d like to start by asking about the E.B. White poem that opens this book. Did that come first or last for you?

Sean: Oh my goodness, what a great first question. The quote definitely came first. Honestly, I’ve been obsessed with that quote for years. I think, back in 2011, I put it on my Instagram account for the tenth anniversary of 9/ll. And interestingly enough, the willow tree E.B. White was writing about lived until around 2010. When I was invited to submit a proposal for this book, I realized I wouldn’t be able to write an entire manuscript by the deadline. But I knew the quote and I already knew I wanted to (try to!) write something that recaptured some of the emotion White had captured, so I included the quote as the second page of proposal (as pictured below).

(Click image to enlarge)

Although it’s not originally a poem, the art director, Jen Keenan, formatted it to look that way. White’s prose is so spare and lyrical at the same time; it totally works in that format. We included the quote at the beginning of the book for the same reason I included it at the beginning of my pitch: By getting readers to understand how the New York community felt about that willow tree, we hoped they would better understand how the community feels about the Survivor Tree–and about the whole city, really. It’s a sort of lens through which to read the rest of the story.

Jules: You dedicate the book, in part, to your cousin Stephen. Is there a 9/11 story there? If it’s too personal, you certainly don’t have to share.

Sean: There’s an allusion to the story in the dedication. My Uncle Stephen (older cousins are often called “uncle” in my family) worked with New York City Fire Department as a safety inspector for a number of years. After 9/11, he was assigned to the pile (what the workers there called Ground Zero) as a sort of safety sheriff for the area. When I was officially offered the book, I actually called him to ask for his blessing. That conversation was very meaningful to me for a number of reasons. For one thing, it was the first time I had really asked him about his experience working there. His descriptions of the pile–and what it would be like for the tree to be buried there–were haunting. They ultimately inspired the spread where the tree is in the dark. The book would be much poorer without this insight and his willingness to talk about a difficult set of memories. I’m grateful to him for both.

Sketch of the pile (Click image to enlarge)

Jules: Can you talk about how the book draws heavily on research about the nature of trauma? Your wife, a clinical psychologist, received training at a research center in South Carolina, and their research informed this book, yes?

Sean: Lucy has specialized training in trauma assessment and treatment from the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center in Charleston, South Carolina. Our family spent a year there before she completed her PhD in 2019. I remembered that she found that training to be very effective (and affecting), so at one point early in the writing process, I had hit a little writer’s block and went to talk to her about it.

I already knew the story should somehow acknowledge traumatic experience, but during that conversation I realized the book wasn’t going to work unless the tree’s trauma actually determined the entire narrative arc. So I asked Lucy, “If the tree was a patient that came to your practice, what would you expect it to say? How would it feel? What would be its trajectory in therapy?” I quickly wrote down her answers on a couple of Post-it notes.

Reconstructing the World Trade Center (Click to enlarge)

There were a number of insights that were taken directly from Lucy’s training and experience treating patients. For example, the tree withdraws from others; it’s sensitive to reminders of what happened; it feels both excited and anxious about its return to Manhattan. For many trauma survivors, community is a defining part of the recovery process, so our tree’s reliance on other trees became important.

The idea I’m probably most fond of is that the tree had a “job.” I wanted to communicate that the tree had a purpose and daily activities that were interrupted by the attacks, so that its recovery could be tracked by the way the tree thinks about that purpose–and how that purpose changes over time. Of course, the tree was planted in Manhattan’s Financial District, so I imagined it had adopted a business perspective, hence being proud of its “job.”

Jules: Did you labor over how to depict the actual tragedy (the collapse of the Towers) in such a way that is honest? You handle it well. You hear a lot of people say such heavy topics shouldn’t exist in picture books (which I disagree with–and clearly you do too).

Reference images (Click first two to enlarge)

Sean: I appreciate that. More than anything I tried to capture the chaos. In that moment, everyone was confused and scared, and it was impossible to really understand what was happening. I took forever on that illustration. I finished it last after working on the art, piecemeal, for months. But I was getting to the deadline, so I delivered what you see in the book. A day after the deadline, I called my editor, Christian Trimmer, to say I was recalling that spread. I told him I didn’t like the art and that was making me uncomfortable. He paused and said something like, “Sean, it’s supposed to make you uncomfortable. It’s doing its job.” I realized he was right.

So, I think the topic is heavy, but I hope the book is a gentle way of approaching it. Picture books are a medium that can be both gentle and genuinely surprising. We rely on page-turns as a storytelling device, after all, although I know some readers may expect every picture book to be gentle all the time. I think that may shortchange the medium. Picture books are remarkable for their ability to tell virtually any type of story and to tell difficult stories in ways that are appropriate for younger ages. I love that about picture books, and I hope to make more books with a startling spread or two, whether their topics are heavy or not.

“It was an ordinary morning. Until it wasn’t.” (Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: Yes, I love how your use of off-kilter panels in that spread [not pictured here] communicates so much of the confusion and chaos. And the use of the panels in the “it was weeks before they found me” spread, and the perspective you provide there, are effective. It must have been such a joy to paint those final spreads with all the many trees and what seems like every shade of green! It is so beautiful to see.

Sean: I was thinking about collapse and falling with those panels, of course, but also broken glass. I wound up studying layouts for action scenes in superhero and fantasy comics to make that work, especially some of Ramón Pérez‘s art in Jim Henson’s Tale of Sand, where he really perfects using panels to show many things happening all at once.

The “found me” spread was part of my original proposal, and it’s still one of my favorites. Panels are really helpful for covering longer stretches of time, and that spread is one example. Originally, when the tree is looking up, it was about seeing that spot of light and the light getting brighter and bigger over the spread. But we could do a lot with depth and distance in those images too, so the top of the pile getting closer became the focus as well.

Sketch of finding the tree (Click image to enlarge)

In regards to those final spreads, thank you! Green is my favorite color (which I don’t think is always apparent from my art, I’ll admit). It was great to “mix” a number of greens in Photoshop and layer them to create the leaves, and I think some orange and periwinkle snuck in as well. I learned a ton about painting trees while working on The Passover Guest, and it was a joy to get back into that painting mindset. I love drawing, but there’s nothing on earth like painting. The tree is starting to relax at that point, and so was the illustrator.

Sketch (Click to enlarge)

“Years passed. I regrew.

I wondered if my city was regrowing too.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

Jules: Now I have to ask: What’d you learn about painting trees on The Passover Guest?

Sean: Ha! Well, cross-hatching is good for a lot of things, but for some reason when I try to crosshatch trees, the leaves (or flowers) feel way too heavy. In Bolivar, I started to experiment with digital watercolor for tree tops, and I liked that effect, but it was a bit too cartoony for The Passover Guest. When I started to paint the cherry blossoms for The Passover Guest, I was still doing a lot of digital watercolor but eventually added gouache and crayon to the trees to create different kinds of weight and levels of transparency–and also value differences (how light or dark something is). By the time I got to This Very Tree, I was using this “digital mixed media” approach extensively.

The result may have a kind of abstract expressionism vibe, for better or worse, but for me, it captures the movement and visual complexity of a tree better than cross-hatching can. At least I hope it does. One of the oddities of being an illustrator is that you often have to figure out your craft on the job. So you can definitely see a development in how I paint trees if you look at my books from, say, 2017 till now. It’s only mildly embarrassing!

Winter sketch (Click to enlarge)

Jules: This book doesn’t explicitly mention 9/11 in the actual narrative. (It shows up in the backmatter.) Can you talk about why?

Sean: When we were talking about the tree’s voice, a big part of the conversation centered on what she would know and what she wouldn’t know. I thought she’d know she lived in New York, but I didn’t think she’d have too much of a sense of what state or country she lived in. Similarly, I didn’t think she’d have any sense of geopolitics or what terrorism is–or even understand airplanes. For her, airplanes cast shadows and that’s it. All this is to say that the book is from the perspective of the tree, so the explanation of 9/11 is also limited to the tree’s experience. And her experience is very immediate.

This meant the book could focus on 9/11 as a personal tragedy, something that occurred to individuals and families, and as a local tragedy, something that had an specific effect on particular communities. I’m concerned the local/personal narrative of 9/11 has become lost – or at least very overshadowed. I think many of us (myself included) have difficulty knowing how to discuss 9/11, because we are uncomfortable with the politics surrounding it. My hope is that by focusing on the local and the personal, This Very Tree creates a space for children to ask questions and for adults to answer. But the book avoids easy answers and simple explanations because, frankly, I don’t think they exist.

(Click cover to enlarge)

THIS VERY TREE. Copyright© 2021 by Sean Rubin. Final illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Henry Holt and Company, New York. All other images reproduced by permission of Sean Rubin. Posted: August 17th, 2021 by jules

***

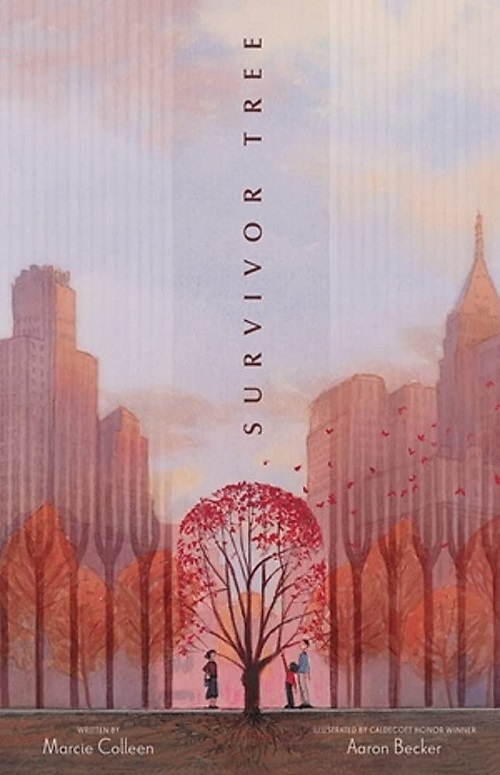

Survivor Tree

“A tree stood steel-straight and proud at the foot of the towers that filled its sky.

It grew, mostly unnoticed, silently marking the seasons.” (Click spread to enlarge)

As does Sean Rubin’s book, Survivor Tree, by author Marcie Collen and illustrator Aaron Becker shines its light on the Callery pear tree that once stood near the Twin Towers (see spread above); was found “crushed and burned” under the rubble after the attacks (“the last living thing pulled from the rubble,” as the author puts in a closing note); was moved to the Arther Ross Nursery in the Bronx on November 11, 2001, with little hope it would survive; and was sent back to near where the Towers once stood after it finally recuperated.

Colleen’s text captures with a spare lyricism the way in which the growing tree changes, pre-9/11, in response to the seasons. One particular spread, pictured below, plays with this in an elegant yet chilling way, a brilliant design choice that captures the moment before one of the planes hit the first Tower.

“Fall.” (Click to enlarge)

With reverence, Colleen communicates the grief and shock of the attacks, as seen through the effects it had on this tree, which becomes “a shattered stump” that is moved to a place with “a different sky.” Her measured pacing is perfect as we see the tree, in its new home with two stone blocks placed next to it (“a memorial of makeshift towers in a makeshift home”), quietly recover–just as many Americans attempted to do.

Becker’s watercolor and colored pencils illustrations truly extend the text with a visual story line about one particular family, whose lives were radically altered by the attacks. He also works wonders with leaves; pay close attention to them throughout the book. Given that Colleen describes the tree in autumn as blazing “red with a million hearts” (capturing the shape and color of the leaves), Becker uses this heart/leaf motif throughout the book and also communicates much emotion with this deep red hue. I love to see what Becker communicates in merely the shadows: When we see in Spring that a bird has built a nest in the tree, while healing away from the Towers, we don’t see the mama bird–but do see her shadow on the book’s verso in a spread that gracefully captures the shift from Winter to Spring.

This isn’t a text that delves into the reasons for the attack; this is not even covered in the book’s closing notes, Colleen explaining that she was teaching on September 11, 2001, and felt unable to tell her high schoolers at the time why this had occurred. She adds, however, that telling the tree’s story may serve as a springboard for conversation:

“I hope readers and their caregivers will find an entry point to a topic that is difficult to comprehend. I still do not have all the answers to the questions my students asked twenty years ago. But this book is what I can give them, and anyone seeking a more hopeful, colorful world.”

Here are some more spreads. …

“Then one day … Buds to blossoms. Blossoms to leaves. Though charred and gnarled,

the tree began to grow. And so it went for almost ten years.

White, green, red, bare. Spring, summer, fall …”

(Click spread to enlarge)

“The tree hesitated to fill the empty sky. People no longer rushed by.

Instead, they stopped and wept beside two forever-filling pools.”

(Click spread to enlarge)

THE SURVIVOR TREE. Text copyright© 2021 by Marcie Colleen. Illustrations copyright© 2021 by Aaron Becker and reproduced by permission of the publisher, Little, Brown, New York.

Posted August 8th, 2021 by Jules

***

A Hundred Thousand Welcomes

welcome the stranger and…offer peace and refuge to those in danger…

Mary Lee Donovan‘s A Hundred Thousand Welcomes (Greenwillow), illustrated by Lian Cho and coming to shelves in October, is like honeysuckle to a bee for young language-lovers–and also a very welcome read (excuse the bad pun) for those moments when the goings-on in the world get you down.

In a short introduction, which notes that the book’s text is written as a poem, readers see a pronunciation guide. This is helpful, because this gentle, lyrical text includes a handful of translations of the English word “welcome.” To boot, Lian Cho weaves pronunciations of these words into the illustrations. In this same introduction, Donovan also notes:

“The call to welcome the stranger and to offer peace and refuge—aman–to those in danger is deeply rooted in ancient traditions and in all major religions. The truth is that ‘we are all migrants on this earth, journeying together in hope.’ In one place or another, at one time or another, in one way or another, every single one of us will find ourselves in search of acceptance, help, protection, welcome.”

(In that excerpt, Donovan is quoting the UNHCR’s Welcoming the Stranger: Affirmation for Faith Leaders.)

Donovan’s poem is an invitation: “Welcome, friend. Welcome. Dear neighbor, come in.” On the opening spread, a girl waves to a family, rushing in during a storm. “We’ll shelter in peace, break bread where it’s warm.” As we read, we see families all over the world doing the same; we see families speaking Mandarin, Lakota Sioux, Indonesian, German, Hindi, Modern Standard Arabic, and more. The opening and closing of the book even includes images of hands fingerspelling “welcome” (pictured above), and on the last spread, Donovan writes: “A hundred thousand welcomes / I sing, / I sign, / I pray.”

A note from Cho (at the book’s close) explains that she intended for food to be an integral part of this story:

“When this story first reached me, I knew that I wanted some aspect of this book to revolve around food. Families from all over the world joyfully coming together and welcoming strangers across a giant table filled with delicious foods from many cultures felt like the right thing to paint in a time when hate and fear are championed.”

She also writes about her efforts to eschew stereotyped images in her artwork: “I had to be creative and determined,” she writes. Her research pays off in these bright, bustling, detailed spreads. There’s a lot to take in, so expect lingering before page-turns. And expect to want to snack afterwards, given all these lush spreads with feasting and food from all over the world. Check out below the grand feast that closes the story. Although I’m working from a digital copy of this book, it looks to me like this feast is a double gatefold. Magnificent.

It’s a big-hearted, compassionate book, Donovan noting in her closing note: “I am not a marcher. I am not a rally-er. I am not a fist shaker. I am not a knitter of hats or a waver of signs. My rage boils down, instead, to ink. This particular river of ink is my love song to our shared humanity and it is my protest against intolerance, injustice, and inhumanity.” For those who feel the same–or even for those who are fist shakers–the book closes with a selection of further reading (picture books!) as well as selected sources.

Here are some spreads.

‘Hellos and How-are-yous /ancient and young.

I bow to your spirit./Selamat datang.’

(Click spread to enlarge)

‘sh?gata./May our meeting be blessed.’ (Click spread to enlarge)

‘May you never know hunger. May peace fill your nights.

May your children’s children grow strong in the light.’

(Click gatefold spread to enlarge)

A HUNDRED THOUSAND WELCOMES. Text copyright© 2021 by Mary Lee Donovan. Illustrations copyright© 2021 by An-Li Cho. Illustrations reproduced by permission of the publisher, Greenwillow Books, New York.

Posted at 7-imp on August 22nd, 2021 by Jules

Julie Davidson (Jules) conducts interviews and features of authors and illustrators at her acclaimed blog, Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, a children’s literature blog primarily focused on illustration and picture books.

Julie Davidson (Jules) conducts interviews and features of authors and illustrators at her acclaimed blog, Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, a children’s literature blog primarily focused on illustration and picture books.