This month marks 61 years since Beverly Kenney committed suicide at the age of 28, for reasons widely speculated upon but never verified. Hailed in the mid-‘50s as the latest and best in a line of towering female jazz singers, compared favorably to Billie, Ella and Sarah, she had the looks, she had the style, she had the versatility, she had critical cred, she had the support of the day’s finest musicians, and she had the ‘it’ that is the stuff of legendary careers. Instead, she ended her days in despair, and alone, in a women’s residence on West 11th Street in Greenwich Village on April 12, 1960, her system overwhelmed by Seconal and alcohol. Little more is known about her now than it was then, and as time passes a key question remains unanswered: Who was Beverly Kenney?

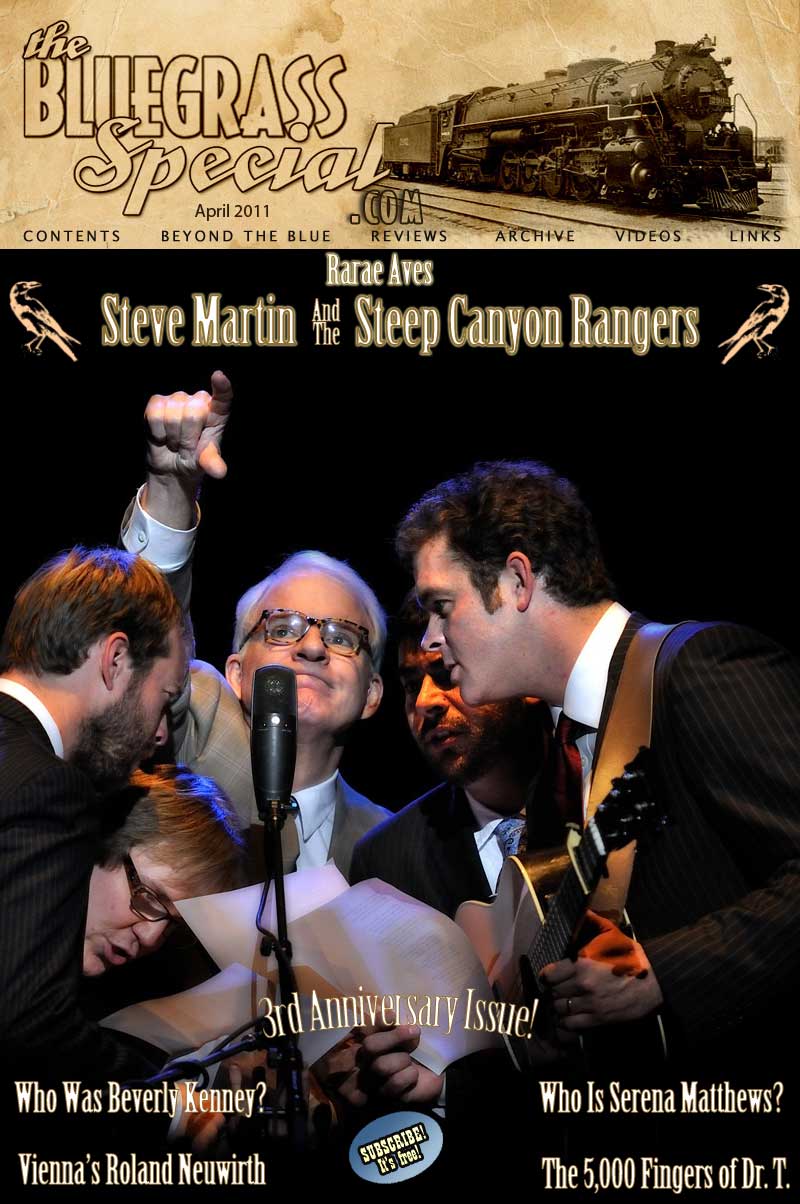

By David McGee

…A story that was the subject of every variety of misrepresentation, not only by those who then lived but likewise in succeeding times: so true is it that all transactions of preeminent importance are wrapt in doubt and obscurity; while some hold for certain facts the most precarious hearsays, others turn facts into falsehood; and both are exaggerated by posterity. –Tacitus

Well let me tell you ‘bout the way she looked

The way she’d act, and the color of her hair

Her voice was soft and cool,

Her eyes were clear and bright

But she’s not there

(The Zombies, “She’s Not There,” 1964)

In 1956 if you knew nothing about Beverly Kenney–and few people did–but were old enough to appreciate adult music in the midst of what one writer calls “the tsunami of rock ‘n’ roll,” you perhaps cued up her debut album, Beverly Kenney Sings for Johnny Smith (and maybe you would have been amused by the cover’s pop-art IBM punch card background, and the pixie-haired singer’s flirty photo, with her left hand partly obscuring the left side of her face as she directs a shy smile at the camera, fixing you with piercing eyes below severe, dark eyebrows), and the first thing you would have heard is a bright, swinging rendition of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Surrey With the Fringe On Top,” from the legendary duo’s smash Broadway musical Oklahoma!

“Chicks and ducks and geese better scurry,” she sings with a genial, swinging swagger over the cool musical backdrop provided by Johnny Smith on guitar, Bob Pencoast on piano, Knobby Totah on bass and Moosie Alexander on drums (all top-drawer jazz musicians who had played with Sinatra, among others). The arrangement is decidedly in the King Cole Trio mode, and in fact the singer’s cool but inviting voice and nuanced rhythmic attack are indebted to Nat, the man with the smoky gray voice. But your first impression, from the gut, might well be, “What’s the big deal?” Which lasts about as long as it takes you to consider what you’ve heard, because you find you want to hear it again. And again. It’s irresistible, captivating, mesmerizing and mysterious all at once. You go deeper into the record and marvel at the incredible beauty and simmering heat of her take on the Gershwins’ “Looking For a Boy,” in which her savvy combination of clipped phrasing in the verses and delicate, emotionally charged legato lines in the choruses delivers a heightened emotional charge composers George and Ira surely would have appreciated; swoon to the lovely classical solemnity of “I’ll Know My Love,” based on the melody from “Greensleeves.” As if to underscore the debt to King Cole, she assays “Sweet Lorraine” as “Ball and Chain,” softening its mood into a saloon song, really a torch version, almost like a prayer in its subdued romanticism sprinkled with cautious fatalism (“each night I pray no one steals his heart away”), her voice silky, vulnerable and alluring over the band’s quiet shuffle. A quick sprint through “There Will Never Be Another You”; a dreamy stroll through “This Little Town in Paris”; a frisky “Moe’s Blues” (written but never recorded by Morgana King, a terrific jazz vocalist herself, but better known as the matriarch of the Corleone family in the first two Godfather films) in which she not only rolls out a bluesy drawl with a suggestion of southern origins but teases with a few bars of frisky scatting, until, finally, the album closes with “Snuggled On Your Shoulder,” the beautiful love song written by Carmen Lombardo and Joe Young. First recorded in 1932 by Bing Crosby, this aching, tender rendition is closer in spirit to Julie London’s 1957 seduction; in fact, Ms. Kenney’s voice has that London smolder in it, and more than a little of the abiding hurt evident in anything Billie Holiday sang, Holiday being the singer with whom Ms. Kenney is most often compared.

‘Moe’s Blues,’ written by Morgana King; Beverly Kenney, from her debut album, Sings for Johnnie Smith (1956)

Then it’s over. Beverly Kenney is gone again. If you were appreciating her work in its own time–over the course of the six albums she made between 1956 and 1960–you knew she got it all right: her enunciation is precise, but soulful, as if she had absorbed every elegant phrase Billy Eckstine had ever sung; all the pauses are in the right place; her understanding of the songwriters’ intent, if her own choices are any indication, is nigh on to infallible as she finds new ways into familiar texts from the Great American Songbook; the many textures of her voice serve not to call attention to her gifts but rather to enhance the context of the musical framework she serves; and her uncanny knack for enlarging the emotions of a song without ever losing control of them, reveals an advanced sensitivity to the complexities of this thing called love.

Downbeat magazine’s Barry Ulanov, a top jazz critic of the era, would become one of Beverly Kenney’s foremost champions in the press. In the February 22, 1956 issue of Downbeat, he wrote: “It looks as if finally a new voice of unmistakable jazz quality has appeared to take its place beside those of Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. The girl to whom it belongs is Beverly Kenney, 23, a New Jersey-ite of very little professional experience, but almost limitless musical possibilities.”

Ulanov would double down on these thoughts when asked to pen the liner notes for Beverly Kenney Sings for Johnny Smith. He wrote, in part: “Several things are immediately noticeable in Beverly’s singing: a soft, almost husky, but never heavy sound; superbly sustained notes that hang on or fall off at her command; precise enunciation that makes every word or phrase splendidly clear–in sum, a fine sense of the meaning of lyrics that takes full advantage of the sound, the sustained notes, the cleanly inflected words and phrases and makes them all part of a moving continuity. That admirable skill–bringing all, every part of a lyric, into play and into the total conception of each individual song–really grips the listener’s attention and holds him close to his speaker all through this record. It’s the kind of achievement only a handful of singers have been able to bring off in jazz–Billie, Ella, Sarah Vaughan in her first LP, Frank in some of his recent collections. But it’s not only Beverly’s voice and shrewd choice of phrase and nuance and understanding of meaning that fix the ear so insistently on her work in this set; it is also the selection of tunes and the backings arranged and played for her.”

‘The Dipsy Doodle,’ Beverly Kenney, from Like Yesterday (1960)

Ulanov was voicing what many Kenney fans today believe: that Beverly Kenney Sings for Johnny Smith is the finest of her six albums. In fact, though, the consistency of her recordings from 1956 to 1960 is remarkable–an argument could be made that her last, Like Yesterday, contains the most sophisticated singing of her career, a real leap forward in her vocal artistry and in her ability to impose her personality on a song but always with respect to the songwriter’s intent. It also contains her single most delightful romp in song on Larry Clifton’s timeless “The Dipsy-Doodle.” Ms. Kenney eats it up–she sings as if she’s smiling all the way through the tenor sax-driven ‘50s R&B arrangement, and simply has a high old time with the dance song’s rhyme schemes warning about some unidentified affliction that results in its victim experiencing bouts of disorganized thinking (“the things you say will come out in reverse/like you love I and me love you/that’s the way the dipsy doodle works”); and the delighted lift in her voice when she sings the word “noodle” in the chorus (“But it’s not your mind that’s hazy–it’s your tongue that’s at fault not your noodle”) has an irresistible heart melting sweetness about it.

That Beverly Kenney is so present on her albums, so vibrant and lively, so full of life in fact, is part of the illusion of Beverly Kenney. During her short professional career, hardly anyone could claim to know much about her. Ralph Patt, a musician who worked with Ms. Kenney on the road in 1956, told author/producer/screenwriter Bill Reed (in essence Ms. Kenney’s biographer, who published his findings in The Last Days of Beverly Kenney, which was once available online at the Scribd website, now defunct, and Mr. Reed is reported to have passed away in recent years): “I remember what a great singer she was but she seemed pretty unhappy and not too stable, so I wasn’t surprised at her untimely death. A great loss!”

Millie Perkins in The Diary of Anne Frank

Jazz singer-pianist Audrey Morris, a friend of Reed’s who performed with Ms. Kenney in Chicago, said: “I’m not much help on Beverly Kenney as she was very inside. I don’t mean aloof–she was lovely and nice to talk to. I suspected severe melancholy, maybe mistook it for homesickness as she spoke frequently of Nicky DeFrancis, her very dear friend. I believe he was working at a piano bar in New York.”

Actress Millie Perkins (who shot to fame when director George Stevens plucked her from child actor obscurity to star in his Diary of Anne Frank film adaptation), who could claim to be Beverly’s best friend, described Ms. Kenney to Bill Reed as “very pensive, moody, but she was wonderful. There was a real melancholy about Beverly. She smiled a lot but she didn’t laugh. She wasn’t jolly, sober. I felt her melancholy came out in her music.”

A true Rashomon story, Beverly Kenney: everyone who knew her and has been tracked down for an interview seemed to have known a different Beverly Kenney, with the only common denominator among their reminiscences being agreement on her underlying despair. True to the theory that those we are closest to and should know best are those who elude us, some of the people closest to Beverly Kenney seem not to have known her as well as they thought–witness Millie Perkins’s remarks (expanded upon in Reed’s book). Witness those of her last lover, Milton Lowenstein, who became executive VP of the advertising behemoth Young & Rubicam but was working at a Bamberger’s department store in New Jersey when he dated Beverly; Lowenstein seemed to think the sessions for her final album, Like Yesterday, were going well. In fact, as Bill Reed learned, Beverly suffered a complete psychological breakdown during the sessions and could complete her work only with the aid of a psychiatrist who was called into the sessions with her. (This is one of several peculiarities of a memoir Lowenstein penned about all the women he had slept with, titled 22 Women; it was never published, and the original manuscript was lost, save for the chapter on Beverly Kenney, which Lowenstein sent to Bill Reed, who includes it in The Last Days of Beverly Kenney.)

In what was one of her last public appearances, and her only appearance on American television, Beverly Kenney appeared on a 1960 segment of the Hugh Hefner-hosted Playboy After Dark show, performing ‘Everything Happens to Me’; Rodgers and Hart’s ‘Mountain Greenery,’ in a jaunty arrangement of the 1926 tune written for the Broadway musical The Garrick Gaieties (and first performed on stage by, of all people, Sterling Holloway); and inexplicably enlists Hefner as a vocalist on a verse of Gus Kahn-Walter Donaldson’s ‘Makin’ Whoopee,’ written for the 1928 musical Whoopee! Saving her best for last, she closes this priceless near-11-minute appearance with a lovely rendition of ‘In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning,’ a David Mann-Bob Hilliard co-write that served as the title track of a classic Frank Sinatra album from 1955.

Thanks to WNYC public radio disc jockey Jonathan Schwartz, who wrote the first in-depth profile of Beverly Kenney for GQ magazine in 1992, and to Bill Reed, whose research filled in some gaps and debunked some of Schwartz’s assertions, we know a bit about the artist’s conflicted family life, and the basics about her career. Beyond this, only speculation, rarely informed, exists, and Beverly Kenney ultimately disappears into the mist of a memory.

A swinging treatment of the Mack Gordon-Harry Warren chestnut, ‘There Will Never Be Another You,’ from Beverly Kenney Sings for Johnny Smith (1956).

Before she and Lowenstein became lovers, Beverly had a torrid affair with Beat generation guru-Greenwich Village intellectual/egomaniac Milton Klonsky. In his GQ article, Schwartz suggested Beverly’s downward spiral was triggered by her breakup with Klonsky, but Millie Perkins, in her interview with Bill Reed, disagreed, pointing out that Beverly’s death occurred two years after the Klonsky affair, that the affair with Lowenstein followed and it was, until the end, a happy time for Beverly, and that Beverly voiced no reservations when Perkins began dating Klonsky.

In a sense, though, Klonsky hovers over the Beverly Kenney story in spirit, if you consider how Klonsky was described by his friend and fellow Beat Generation gadfly and authentically towering writer/critic Seymour Krim (who coined the phrase “radical chic” years before Tom Wolfe appropriated it), who once wrote: “If ever there was a cat alone, not melodramatically, sobbingly, literarily, showily, but ice-locked in a moonscape beyond our knowledge and performance, it was Milt.” Replace “Milt” with “Beverly” and you’re onto something.

Nevertheless, you find, in the end, she’s not there.

Nevertheless, you find, in the end, she’s not there.

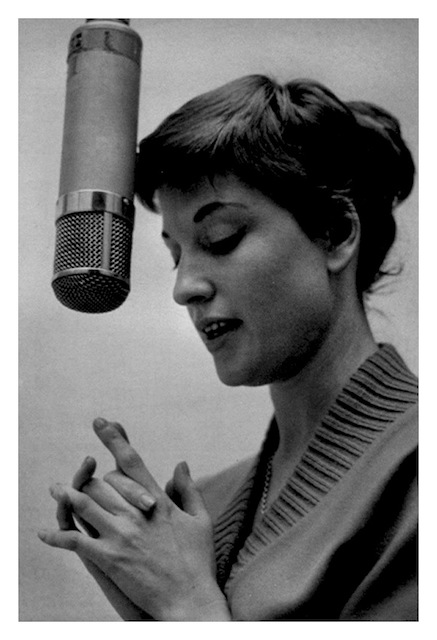

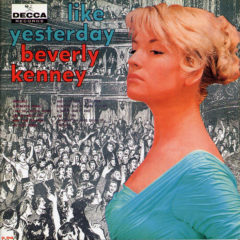

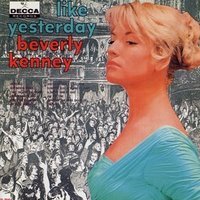

She looks different on every album cover, especially on the final album, Like Yesterday. Issued in 1960, the album’s cover shot is truly unsettling: superimposed over a black and white shot of a cheering crowd looking up at her, a bleached blonde Beverly–and rather shabbily bleached blonde at that–appears with eyes in a half-closed glare, her mouth downturned in disdain and her facial expression radiating utter contempt as she directs her unseeing gaze towards the rabid throng below. Jonathan Schwartz describes her figure as “voluptuous,” but in the few full-body photographs extant, she appears tall and thin (Reed says she was “five-feet-six, or five-feet-seven, well proportioned”), or athletic, but hardly voluptuous in the classic sense. In one photograph she looks like she might have red hair; in another, blonde; in still another, jet black and cut short, so that she appears not unlike young Audrey Hepburn. She had something, though, an “it” quality that led to an offer to pose for Playboy. She accepted, but the session did not go well, and the resulting images were destroyed. (Which in itself begs the question as to why this intensely private woman would literally bare herself before a stranger’s camera and be thus exposed to the reading public. It doesn’t add up, any more than a lot of other facts about Beverly Kenney don’t add up.)

‘That’s All,’ a 1952 song written by Alan Brandt and Bob Haymes and first recorded by Nat King Cole in 1953. This recording is from a 1954 demo session for Decca Records, with Beverly Kenney accompanied by pianist Tony Tamburello.

Bill Reed: “I do know that if you look at the photos she never, ever photographs, even remotely, the same way twice. Mort Lowenstein knew her for a couple of years and had an affair with her for at least a year, and he said that no photograph ever captured the way she looked. There was no photograph that was a likeness. I don’t know how voluptuous she was; I don’t know. But I do know that Jonathan could have gotten a wrong impression from a photograph. But in a clip from the Steve Allen Show, where she appeared, she looked–and here she was for the first time in motion–so much more beautiful. I watched it with Mort, and I asked him, ‘Is that the way she looked, Mort? Is that the way she looked?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ She was as beautiful as any movie star, as beautiful as Elizabeth Taylor, unbelievable.”

Reed says three video clips of Beverly once existed, but only two are still around. One is presented above, from Playboy After Dark, a tantalizing 10:46 glimpse of Beverly in person, talking and singing live. The other was uploaded to a Japanese website and looks to be a live clip of Beverly, but it was pulled with a notice of a copyright infringement claim by the Universal Music Group. Naturally. An audio interview exists, and is embedded below, although its source and date are not identified; even Bill Reed has not been able to ascertain its origins, but someone is noodling in a piano in the background and the ambience is definitely live—a club or recording studio, perhaps. During the interview’s two-minutes-plus duration, Beverly discusses her thoughts on being considered a jazz rather than a pop singer and identifies her influences as being chiefly instrumentalists–she names saxophonist Stan Getz in particular—rather than vocalists. Speaking to Burt Korall, then co-editor of The Jazz World, for the liner notes for her sixth and final album, Like Yesterday, she waxed enthusiastic about Billie Holiday–“Billie was the ultimate. She put it out on the line every time she sang. I can never forget her.”–but reserved more affection for Getz: “When I first began singing, Stan’s sound and phrasing charmed me. I felt his way on the tenor should be mine as a singer.”

The only recorded interview with Beverly Kenney yet discovered beyond the Playboy After Dark appearance, interviewer unknown, date unknown, barely more than two segmented minutes in duration. She discusses her influences (she named Stan Getz and says ‘I think I was more influenced by instrumentalists’ than by other singers) and her thoughts on being considered a jazz singer rather than a pop vocalist.

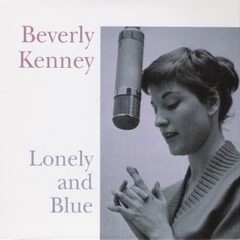

The six albums Beverly Kenney recorded in her lifetime–the first three for the independent Roost label (or Royal Roost, as its label indicated), the last three for Decca—are finally all available, along with recent anthologies, in the U.S. For many years, her albums could be found in print only in Japan, where Beverly Kenney remains a major cult figure. Many Japanese fans labor under the delusion that Beverly died in a hotel fire, but more important, their reverence for Ms. Kenney’s artistry is rooted in what the Japanese call “hakanasa,” a word that has no English translation but is described by one of Bill Reed’s Tokyo correspondents as “‘fragility’ or ‘frailty’ in a good and highly aesthetic sense. We have perhaps somehow intuitively sensed, aestheticized and adored that tragic side of her personality.” In recent years, thanks to Bill Reed’s archeological digs, three albums of non-album tracks have been issued: Lonely and Blue (available at Amazon for a pricey $60, these are radio transcriptions recorded in 1952 before she was signed to Roost, and already quite accomplished, accompanied by some of the same musicians who would join her on Roost); Snuggled On Your Shoulder (also on Amazon, going for $40 used; sessions cut in 1954 that may have been, in effect, her demo for Roost, as it sounds like the template for Sings for Johnny Smith, right down to the song selection; an expanded edition of this album, assembled by Bill Reed, includes four wonderful live vocal and piano performances recorded in an unidentified club on an unidentified date, but are fascinating artifacts–the only live performances we have of Beverly Kenney–documenting her mastery of the stage as well as the studio on “Surrey With the Fringe on Top,” “Violets For Your Furs,” “Mountain Greenery” and “Almost Like Being In Love”); and What Is There to Say? (a pricey $86 at Amazon; previously unreleased tracks cut between 1954 and 1958, including some live radio performances, the audio interview clip, and even some tap dance instruction records Beverly made during this time). As with the studio albums, these three rarities albums showcase a remarkably consistent artist, and also give us the only glimpse we have of her in something approaching a live performance, albeit one without an audience. In this, we find her looser, with an easy, swinging grace in her vocals and a carefree delivery that suits the temperament of her singing. It’s not necessary to be a completist to appreciate these discs; with the exception of the eclectic collection that is What Is There To Say? the other two collections amount to complete, well-considered albums. What is not evident in these, or in the final testament of Like Yesterday, is any clue whatsoever of where she might have been heading as a musical artist, other than where she was on the morning of April 12, 1960, when it all ended. In death as in life, Beverly Kenney bequeathed us as much speculation about her life as she left verifiable facts.

The six albums Beverly Kenney recorded in her lifetime–the first three for the independent Roost label (or Royal Roost, as its label indicated), the last three for Decca—are finally all available, along with recent anthologies, in the U.S. For many years, her albums could be found in print only in Japan, where Beverly Kenney remains a major cult figure. Many Japanese fans labor under the delusion that Beverly died in a hotel fire, but more important, their reverence for Ms. Kenney’s artistry is rooted in what the Japanese call “hakanasa,” a word that has no English translation but is described by one of Bill Reed’s Tokyo correspondents as “‘fragility’ or ‘frailty’ in a good and highly aesthetic sense. We have perhaps somehow intuitively sensed, aestheticized and adored that tragic side of her personality.” In recent years, thanks to Bill Reed’s archeological digs, three albums of non-album tracks have been issued: Lonely and Blue (available at Amazon for a pricey $60, these are radio transcriptions recorded in 1952 before she was signed to Roost, and already quite accomplished, accompanied by some of the same musicians who would join her on Roost); Snuggled On Your Shoulder (also on Amazon, going for $40 used; sessions cut in 1954 that may have been, in effect, her demo for Roost, as it sounds like the template for Sings for Johnny Smith, right down to the song selection; an expanded edition of this album, assembled by Bill Reed, includes four wonderful live vocal and piano performances recorded in an unidentified club on an unidentified date, but are fascinating artifacts–the only live performances we have of Beverly Kenney–documenting her mastery of the stage as well as the studio on “Surrey With the Fringe on Top,” “Violets For Your Furs,” “Mountain Greenery” and “Almost Like Being In Love”); and What Is There to Say? (a pricey $86 at Amazon; previously unreleased tracks cut between 1954 and 1958, including some live radio performances, the audio interview clip, and even some tap dance instruction records Beverly made during this time). As with the studio albums, these three rarities albums showcase a remarkably consistent artist, and also give us the only glimpse we have of her in something approaching a live performance, albeit one without an audience. In this, we find her looser, with an easy, swinging grace in her vocals and a carefree delivery that suits the temperament of her singing. It’s not necessary to be a completist to appreciate these discs; with the exception of the eclectic collection that is What Is There To Say? the other two collections amount to complete, well-considered albums. What is not evident in these, or in the final testament of Like Yesterday, is any clue whatsoever of where she might have been heading as a musical artist, other than where she was on the morning of April 12, 1960, when it all ended. In death as in life, Beverly Kenney bequeathed us as much speculation about her life as she left verifiable facts.

***

SINGER FOUND DEAD

Pills Are Scattered Beside

Beverly Kenney in Room

Beverly Kenney, a 26-year-old singer, was found dead last evening in her room at the University Residence Club, 45 West Eleventh Street. Other tenants had noticed lights under her door and said that her radio had been playing since Monday evening. They called the manager, Paula Troike, who summoned the police. The body of the singer, clad in a nightgown, was found on the floor, with pills scattered about. The nature of the pills was not immediately identified. There was no note. An autopsy was ordered to determine the cause of death. According to the manager, Miss Kenney had lived at the hotel since September. (New York Times, April 13, 1960)

Beverly Kenney was born in Harrison, New Jersey, on January 29, 1932, the oldest of nine children (four boys, four girls, and a brother, Charles, who died in infancy; the Kenney parents divorced after Beverly was on her own, and two of her brothers are actually from her mother’s second marriage) in a blue-collar Catholic family. In addition to Beverly, the Kenney children were/are Helen, Katy, Jane, Charlene, Tom, Stephen and Michael. Her childhood seems to have been unremarkable, given that neither Jonathan Schwartz nor Bill Reed uncovered anything telling in her youthful pursuits in Harrison. A family member wrote to Reed: “Yes, the family had problems, but if I recall correctly Jonathan Schwartz painted a bad picture of our family. All of the siblings are very close, and Beverly was very much loved.”

By 1953 Beverly was living in New York City, her life a hand-to-mouth affair supported by her job at Western Union, singing birthday greetings over the phone to kids from eight to 80. She became a second mother to her younger sister Charlene (now deceased) during this time, and Charlene often spoke enthusiastically about sleepovers with Beverly in New York that included sightseeing trips and visits to musical venues of all types. In 1954 she cut a demo with piano player Tony Tamburello–quiet, intimate settings for an eerie interpretation of “That’s All,” “Ball and Chain,” a playful “A Foggy Day,” a luscious, romantic but rhythmically playful “There Will Never Be Another You”–that became the basis for her first Roost album, Sings For Johnny Smith in 1956. But at the end of ’54 she relocated to Miami Beach, where she started singing professionally at the Black Magic Room. For four months in 1955 she sang with the Dorsey Brothers’ band, but though the Dorseys liked her, Beverly is quoted in the liner notes for her fifth album, the masterpiece Born To Be Blue, that “they thought I was too much of a stylist for the band. After a few months on the road, I left and returned to New York.” Back in Manhattan, she worked in clubs with George Shearing, Kai Winding, Don Elliott, and “it felt good. I found it easy to relate to jazz. And jazz can be a wonderful teacher if your ears are open.” She was signed to Roost after touring the Midwest, with the Sings For Johnny Smith album arriving in 1956.

‘Where Can I Go Without You,’ a beautifully nuanced performance by Beverly Kenney of a Peggy Lee-Victor Young co-write, with Ellis Larkins on piano, conducted by Hal Mooney, from the Born to Be Blue album (1959)

‘I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry,’ Beverly Kenney, a 1944 torch song and now jazz standard, with music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Sammy Cahn. It was introduced on stage by film star Jane Withers in the show Glad To See You, which opened and closed in Boston, never making it to Broadway. Frank Sinatra recorded it twice, in 1946 and 1958; Sarah Vaughan cut it in 1963, Ray Charles in 1964, Linda Ronstadt in 1983, among many others. This recording is from Ms. Kenney’s 1956 Roost album, Come Swing With Me.

It wasn’t as smooth as all that, though. She played a lot of dives all over the country, and plenty of swell joints, too–“I’m opening one of the top jazz rooms,” she wrote home to her family when she was in Chicago to inaugurate the legendary new home of Mr. Kelly’s. She was constantly on the move–“the nomadic life of a freelancer,” Jonathan Schwartz observed in his groundbreaking GQ profile. Toronto, Rochester, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Chicago. Schwartz saw something pathological driving Kenney’s wanderings:

Beverly Kenney left Harrison, New Jersey, as fast as she could. She came from a huge Catholic family in a blue-collar town, which she fled, not with malice but, it might be assumed, with a certain kind of panic built on claustrophobia, and a secret knowledge far too threatening for her to examine. She was rich in overview. She was wise. She was significantly empathetic.

She might have realized this gradually, or understood it in one grand moment, an epiphanic fraction of a second in which truth came flooding into the teenage girl she had so recently been. It’s possible she felt helpless, falling through dreams, drifting above her sleeping family and away into the night, passing through the darkness into the territory of the Outsider while maintaining a credible radiance during the day-to-day of it. She hid out inside herself, swamped in the guilt of her elevation. All Beverly Kenney could do was run.

Once the albums started appearing, come 1956 to 1960, finding Beverly becomes a challenge. Oh, there were great reviews, and shows in important places, and on record she was accompanied by ace players from the New York jazz scene, including the legendary guitarist-educator Johnny Smith. She signed on with manager/agent Ivan Mogull, who insinuated to Schwartz, for no good reason, that he had a one-night stand with her. But things were looking up for the artist, and in another letter home quoted in the GQ article, she offered an upbeat appraisal of her current prospects: “I’m enjoying a bit of public appreciation. As usual, I have complaints about the backup music, but my loyal esoteric fans are with me anyway.”

Turns out she disdained two things in particular–strings on her records and being photographed. “If she could have sung behind a screen, she would have,” Mogull told Schwartz. “She hated being photographed. She thought strings were hokey.”

To this Mogull added one chilling postscript: “She was always in some kind of pain.”

‘The More I See You,’ from Beverly Kenney With Jimmie Jones and The Basie-ites (1957). Freddie Green (guitar), Eddie Jones (bass), Jimmy Jones (piano/arranger), Jo Jones (drums), Joe Newman (trumpet), Frank Wess (flute, tenor sax).

You wouldn’t know of her pain from listening to the records. There was yearning, there was heartache, there was longing, but at day’s end she exuded the optimism of a true romantic. Maybe she didn’t have enough of a tragic edge to capture the press and public’s attention on a Billie Holiday scale. The pain Mogull speaks of is subtextual, not front and center, when she sings.

She made good records with great players. In addition to Sings for Johnny Smith these number: Come Swing With Me (1956), with the Ralph Burns Orchestra, Milt Hinton on bass, merited this observation from Barry Ulanov in the liner notes: “Beverly’s abiding quality is freshness, not just the shine of the new, you understand, but the sound and style of a bright young voice all her own. Beverly has her own identity, for all the resemblance to the queen of jazz stylists, Billie Holiday, a breezy identity with no traces of the hackneyed and the worn on the edges, in the center or anywhere.”

She made good records with great players. In addition to Sings for Johnny Smith these number: Come Swing With Me (1956), with the Ralph Burns Orchestra, Milt Hinton on bass, merited this observation from Barry Ulanov in the liner notes: “Beverly’s abiding quality is freshness, not just the shine of the new, you understand, but the sound and style of a bright young voice all her own. Beverly has her own identity, for all the resemblance to the queen of jazz stylists, Billie Holiday, a breezy identity with no traces of the hackneyed and the worn on the edges, in the center or anywhere.”

Beverly Kenney with Jimmy Jones and the Basie-ites (1957, with Freddie Green on guitar, Eddie Jones on bass, Jimmy Jones on piano and credited as arranger, Jo Jones on drums, Joe Newman on trumpet, Frank Wess on flute and tenor sax. “The More I See You,” “Old Buttermilk Sky,” “A Fine Romance,” “Makin’ Whoopee,” even “Mairzy Doats” are among the songs. “It is altogether to Beverly Kenney’s credit that she fits in so well with these interpretations of the tunes she herself has chosen so well,” writes her musical Boswell, Barry Ulanov, in the liner notes. “And she doesn’t just fit in: she moves in. This is her natural habitat–or at least she makes it sound that way, as much at ease with a jumping combo of this kind as with the studio orchestra Ralph Burns led for her in her last date or the Johnny Smith Quartet with which she first recorded.”

Beverly Kenney with Jimmy Jones and the Basie-ites (1957, with Freddie Green on guitar, Eddie Jones on bass, Jimmy Jones on piano and credited as arranger, Jo Jones on drums, Joe Newman on trumpet, Frank Wess on flute and tenor sax. “The More I See You,” “Old Buttermilk Sky,” “A Fine Romance,” “Makin’ Whoopee,” even “Mairzy Doats” are among the songs. “It is altogether to Beverly Kenney’s credit that she fits in so well with these interpretations of the tunes she herself has chosen so well,” writes her musical Boswell, Barry Ulanov, in the liner notes. “And she doesn’t just fit in: she moves in. This is her natural habitat–or at least she makes it sound that way, as much at ease with a jumping combo of this kind as with the studio orchestra Ralph Burns led for her in her last date or the Johnny Smith Quartet with which she first recorded.”

‘A Woman’s Intuition,’ a tune written in 1951 by Victor Young and Ned Washington, first recorded by Lee Wiley and Bobby Hackett with Joe Bushkin and His Swinging Strings. Beverly Kenney’s version with Ellis Larkins on piano is from her 1958 album, Sings for Playboys, her Decca debut.

Sings for Playboys (1958), her Decca debut, and one of her most beautiful album-length exercises, features Ellis Larkins on piano and celeste in a spare, intimate setting capturing the singer in a wee small hours mood of thoughtful introspection leavened by a touch of wry, knowing humor. “A Woman’s Intuition” is a devastating, low-key recognition of something coming apart but also a declaration of intent to make it work, with Larkins adding ruminative, concise piano musings to the close-miked, raw vocal; the saloon-style flirtation of “What Is There To Say”; the wistful longing for companionship in the bluesy piano ballad, “A Lover Like You”; a playful suggestion of impending romance in a soft, probing ballad rendition of “Try a Little Tenderness”; and, resonant of the style of her first album, a frisky, cheery “A-You’re Adorable,” one of Nat King Cole’s classics. If this was her rebuttal to those who said she needed to sing with strings, then it could hardly have been more persuasive in her favor.

Sings for Playboys (1958), her Decca debut, and one of her most beautiful album-length exercises, features Ellis Larkins on piano and celeste in a spare, intimate setting capturing the singer in a wee small hours mood of thoughtful introspection leavened by a touch of wry, knowing humor. “A Woman’s Intuition” is a devastating, low-key recognition of something coming apart but also a declaration of intent to make it work, with Larkins adding ruminative, concise piano musings to the close-miked, raw vocal; the saloon-style flirtation of “What Is There To Say”; the wistful longing for companionship in the bluesy piano ballad, “A Lover Like You”; a playful suggestion of impending romance in a soft, probing ballad rendition of “Try a Little Tenderness”; and, resonant of the style of her first album, a frisky, cheery “A-You’re Adorable,” one of Nat King Cole’s classics. If this was her rebuttal to those who said she needed to sing with strings, then it could hardly have been more persuasive in her favor.

(Ellis Larkins, who had a chance to observe Ms. Kenney close up on sessions for two albums, described her to Jonathan Schwartz as “very deep,” but added: “You could sense there was inner trouble. She was a loner, in a way of speaking.”)

Born To Be Blue (1959) is a pop-jazz masterpiece, with Beverly’s subtlest singing on record, deeply measured and deeply felt, every note weighted precisely for its greatest impact in the context of the elegant, understated orchestral arrangements by Hal Mooney and Charlie Albertine, with Charlie Shavers standing out on trumpet (his filigrees in “For All We Know” could not be more to the point or more evocative and right for the moment). If Sings for Playboys was proof Ms. Kenney needed no help from strings in order to be a compelling romantic singer, her interaction with the strings here is an equally assertive demonstration of how effectively, and from the heart, she could respond to empathetic string arrangements. “I found it most comfortable working with Hal and Charlie,” Beverly is quoted in the liner notes. “Both are talented and knowing; their accompaniment was helpful, never overbearing. I was out there free, singing these romantic/blues tunes the way I wanted to.” In these same notes, she offers as close to a mission statement as she ever would in print. “What I have always wanted in my work is the completeness and balance that is Billie Holiday,” she says. “Billie is an experience; she feels, translates, puts it on the line, and you never forget what she has said.” She embodies her own description of Billie on the lush Mel Torme-Robert Wells-penned title track.

Born To Be Blue (1959) is a pop-jazz masterpiece, with Beverly’s subtlest singing on record, deeply measured and deeply felt, every note weighted precisely for its greatest impact in the context of the elegant, understated orchestral arrangements by Hal Mooney and Charlie Albertine, with Charlie Shavers standing out on trumpet (his filigrees in “For All We Know” could not be more to the point or more evocative and right for the moment). If Sings for Playboys was proof Ms. Kenney needed no help from strings in order to be a compelling romantic singer, her interaction with the strings here is an equally assertive demonstration of how effectively, and from the heart, she could respond to empathetic string arrangements. “I found it most comfortable working with Hal and Charlie,” Beverly is quoted in the liner notes. “Both are talented and knowing; their accompaniment was helpful, never overbearing. I was out there free, singing these romantic/blues tunes the way I wanted to.” In these same notes, she offers as close to a mission statement as she ever would in print. “What I have always wanted in my work is the completeness and balance that is Billie Holiday,” she says. “Billie is an experience; she feels, translates, puts it on the line, and you never forget what she has said.” She embodies her own description of Billie on the lush Mel Torme-Robert Wells-penned title track.

‘Born to Be Blue,’ a Mel Tormé-Robert Wells gem featured as the title track on Beverly Kenney’s pop-jazz masterpiece from 1959 with orchestral arrangement by Hal Mooney and Charlie Albertine, whom the artist praised for arrangements that allowed to be ‘out there free, singing these romantic/blues tunes the way I wanted to.’

Finally, Like Yesterday (1960), despite its troubling cover shot, is a thoroughly delightful dozen of pop-jazz numbers. The repertoire ranges far and wide: a lighter-than-air shuffle of “Sentimental Journey”; a dreamy, vibes-enriched “What a Diff’rence a Day Made”; a swooning take on “A Sunday Kind of Love” in a low-key arrangement with discrete saloon piano stylings and smoky tenor sax moans supporting Ms. Kenney’s airy, sustained vocal lines and bluesy dips into a lower register; the abovementioned delight of “The Dipsy Doodle” with its swinging R&B arrangement and Ms. Kenney’s utterly captivating vocal, at once flirtatious and innocent in a Betty Boop kind of way. Reeds (Jerome Richardson), woodwinds, vibes (by Johnny Mae), Chuck Wayne on guitar, drummer Ed Shaughnessy (bound from here for Count Basie’s band and then to a lengthy gig with The Tonight Show band under the direction of Doc Severinsen)–a backing unit the equal of any Beverly had worked with, and to which she responded, despite her inner turmoil threatening to sink the entire project, with remarkable performances every time the tape rolled.

Finally, Like Yesterday (1960), despite its troubling cover shot, is a thoroughly delightful dozen of pop-jazz numbers. The repertoire ranges far and wide: a lighter-than-air shuffle of “Sentimental Journey”; a dreamy, vibes-enriched “What a Diff’rence a Day Made”; a swooning take on “A Sunday Kind of Love” in a low-key arrangement with discrete saloon piano stylings and smoky tenor sax moans supporting Ms. Kenney’s airy, sustained vocal lines and bluesy dips into a lower register; the abovementioned delight of “The Dipsy Doodle” with its swinging R&B arrangement and Ms. Kenney’s utterly captivating vocal, at once flirtatious and innocent in a Betty Boop kind of way. Reeds (Jerome Richardson), woodwinds, vibes (by Johnny Mae), Chuck Wayne on guitar, drummer Ed Shaughnessy (bound from here for Count Basie’s band and then to a lengthy gig with The Tonight Show band under the direction of Doc Severinsen)–a backing unit the equal of any Beverly had worked with, and to which she responded, despite her inner turmoil threatening to sink the entire project, with remarkable performances every time the tape rolled.

***

On Cesarean Birth

I curled my body small

in hiding

to escape the view

of those who sough to start the

flow

of waters long since overdue.

And watched in horror

Cautious silver

part the roof of my Capri

And heard the cry of anguished

protest

The first of many wrought from

- –BK

The romance with Milton Klonsky brought out another side of Beverly’s artistry, however briefly, when the poetic muse struck and she penned the above verse, the only poem of hers that has ever surfaced. Only Milt Lowenstein and Millie Perkins provide any eyewitness accounts of Klonsky and Kenney a deux, and both agree on the genuine affection they displayed when together in public–Lowenstein, in fact, was smitten by Beverly when she was in thick with Klonsky, and, being a casual friend of Klonsky’s, was often invited out with them. Those were occasions of deep, unspoken longing for Lowenstein, who wanted Beverly for himself but resisted making a pass at her as long as she and Klonsky were an item. Finally, following a bitter falling out, Beverly broke it off with Klonsky, who took it hard–“he was acting very irrational, yelling and screaming and carrying on in general–all in a poetic manner, of course,” Lowenstein writes in his memoir–and it fell to Lowenstein to issue an ultimatum to the ex-boyfriend to stay away from Beverly or face dire consequences in the future. With the field clear, Lowenstein had the girl of his dreams all to himself.

“Finally I had this beautiful, happy-go-lucky, talented, fun-to-be-with girl,” Lowenstein writes. “Beverly was a joy to be with. She had a very active imagination and a bit of the Irish devil in her. We started seeing each other regularly and most of the time she would spend the night.” The Irish devil in her reared its head one day when she answered a knock on her apartment door stark naked, thinking she would greet Lowenstein with a special surprise. When she opened the door, she was startled to find an equally startled UPS delivery man standing in the hall with a package for her.

Describing Beverly’s aplomb onstage, Lowenstein recalls a night at the Village Vanguard–“a breeding ground for stardom”–when “two cigar smoking guys with two world-class bimbos” persisted in loud conversation even after the music started. After “a rather ungentlemanly remark” one of them directed at Beverly as she sang “I Long for a Lover, A Certain Kind of Lover,” Lowenstein and his friend Nicky Hilton (playboy and former husband of Elizabeth Taylor) jumped the boors “in a blink of an eye and before we could throw our second punches, the bouncer had ejected the two cigars and the bims. Beverly hardly missed a note but did introduce us to the crowd to loud applause when she finished her song. She sure was fun.”

‘I’ll Know My Love,’ built on the melody from ‘Greensleeves’ and included on Beverly Kenney’s debut album, Sings For Johnny Smith (1956).

At Christmas in 1955, Beverly gave Mort a sterling silver disc with the following sentiments engraved on it:

All the reasons why I like (or love you)

You are fun, patient, quietly intelligent, calm and manly–neither a snob or

Intimidated by snobs–you like me–you smell good and sweet and clean.

You have tact.

You’re mushy.

You taste good.

On the reverse side:

All the reasons why I hate you.

You never buy me flowers–you snore loudly–you are not even half rich–you

Have not mentioned marriage since I said yes–your apartment is too small–

You don’t sleep in P.J.s

Christmas 1955 BK

To Mille Perkins, Beverly “was wonderful. She was the warmest, sweetest–to me–giving person that I had ever met. Beverly picked me out as a friend. We would go to the movies together, we ate together. The first time I had the flu. I had a terrible fever, a terrible cold. Beverly came over, she made hot tea, lemon in it, a giant swig of scotch. She said, ‘Drink this, you’ll feel better tomorrow.’ I drank it and felt totally better the next day. From now on in that’s what I do when I get the flu.”

Milton Klonsky, Beat guru and Beverly Kenney’s lover. ‘I’m famous, not so much for what I’ve written,’ he said, ‘as for the cyclotron of my personality.’ Following their breakup, Klonsky spread rumors that Beverly and actress Millie Perkins were lesbian lovers. ‘If I had known or thought about lesbianism, I might have slept with Beverly,’ Ms. Perkins said recently.

Forever embittered by Beverly dumping him, Klonsky apparently began spreading a rumor about Millie and Beverly being lesbian lovers. Jonathan Schwartz asked Perkins about it when researching his GQ article. When Bill Reed broached the subject, Perkins was quick with a reply: “Bill, you must believe me. I had no concept of lesbianism. That’s how naïve I was. Until I moved to Hollywood and married Dean Stockwell, Dean told me about lesbians. I had no idea.’ She told me she had never heard of pot until she married Dean Stockwell. Then Millie added–and these were her exact words: ‘But you know, if I had known or thought about lesbianism, I might have slept with Beverly.’ And I said, ‘Can I print that?’ And she said, ‘Why yes, I don’t care.’ Millie’s really an old hipster.” (Perkins’s full response to the lesbian question is online at Reed’s website http://chilledairtext.blogspot.com/2007/01/beverly-kenney-continued.html. A word to the wise, too: the Bill Reed-assembled version of Snuggled On Your Shoulder contains a hidden track titled “Gay Chicks.” It’s not about lesbians–it concerns barnyard poultry frolicking about and is based on an old African-American saying, “A chicken ain’t nothin’ but a bird.”)

Things began to sour between Lowenstein and Beverly some time deep into their relationship–he doesn’t specify the exact date–when he treated her to a night out at a well-received off-Broadway production of The Boyfriend. Midway through the show, Beverly insisted she wanted to go home. “She seemed a bit distant, and said she just was not in the mood for it, and so we walked back to my apartment.” Once back at Lowenstein’s, Beverly retired to the bathroom. Fifteen minutes passed–fifteen minutes of absolute quiet that unnerved Lowenstein to the point where he called out to Beverly but received no response. Again he called her name; again, silence. Kicking in the bathroom door, he found Beverly sprawled on the floor, unconscious, an empty Seconal bottle beside her. After checking to be sure she was breathing, he dragged her into a cold shower. When she came to, she told him she had taken three pills before flushing the rest down the toilet. A moment later, though, she said, “I took the whole bottle.” Lowenstein immediately called an emergency ambulance, which came quickly. After the attendants had examined Beverly and determined her to be out of the woods, she fell asleep; she slept soundly through the night, while Lowenstein, scared out of his wits, sat beside her on the bed, checking every so often to be sure she was breathing. When she awoke the next morning, Lowenstein writes, “She felt terrible, but she was alive! As she recovered, I tried to find out from her why she did it. She said she couldn’t imagine what possessed her to take the pills, what a stupid thing to do, and of course she would never do it again.” Six months later, though, Beverly, with Lowenstein unawares, checked herself into Bellevue as Anne Kenney, telling the on-duty nurse that she felt she was going to harm herself. Her chart, Lowenstein remembers, “had a big red suicidal stamped on it.”

‘A Sunday Kind of Love,’ a jazz standard written by Barbara Belle, Anita Leonard, Stan Rhodes and Louis Prima, published in 1946. Beverly Kenney, from her final album, 1960’s Like Yesterday.

Beverly began seeing a psychiatrist, but Lowenstein felt their relationship collapsing. Seeing little progress ensuing from Beverly’s thrice weekly psychiatrist visits, he admits he “had lost a lot of my enthusiasm for our relationship as it became more scary and less comfortable.” Upon her return from a series of club dates, she and Lowenstein came to a mutual agreement to part ways, at least temporarily. She took a room at the University Residence Club on West 11th Street. Lowenstein continued to pay for her psychiatrist visits, and even became a patient himself for a bit. A few months later Lowenstein says Beverly called to tell of a new love interest in her life, a name yet unrevealed to this day.

He recalls it being “about 2:30 on an April afternoon” when his best friend at the Bamberger’s department store in Newark rushed into his office (Lowenstein was men’s sportswear buyer) saying he had heard a radio report that Beverly had committed suicide. A disbelieving Lowenstein was sure his colleague meant Beverly Aadland, who made headlines when her mother accused Errol Flynn of having a sexual relationship with her underage actress daughter, who was in fact only 17 and in Flynn’s company when he died of a heart attack on October 14, 1959. Nevertheless, Lowenstein raced out to pick up a late edition of the Newark News, and there, splashed on the front page, was the report of Beverly Kenney’s suicide from an overdose of sleeping pills. Numbed by the news, “heartsick, scared and disoriented,” Lowenstein repaired to his Greenwich Village apartment. Out of habit, he checked his mailbox and found inside it “one skinny invitation-size envelope. I instantly recognized the handwriting. My heart stood still.”

‘I Hate Rock and Roll,’ a live performance from The Steve Allen Show of her only self-penned song, co-written with Ray Passman

It was a note from Beverly, short and sweet, addressing him in the nickname she had given him: “Dear Sven, I really did love you, nothing was your fault. Thanks for everything. Please see that I’m cremated. Love and Goodbye, BK.”

Apparently unaware of Beverly’s previous suicide attempts, Millie Perkins was shocked and surprised when she heard the news of her friend’s death. To Bill Reed she said: “They say she committed suicide, correct? I didn’t know that that was happening with Beverly. We talked a couple of times on the phone. She sounded fine. I was beginning to earn a living and get out there. Maybe she needed money. She never asked me for money. Did she need money?

“Beverly was very pensive, moody, but she was wonderful. She was one of the important people in my beginning years. I know that when she died I was shocked, and I went into difficult times about it because all of a sudden I felt guilty. Oh, my god, my friend Beverly. Maybe I should have called, but I was shooting a movie, having a strange little experience of my own. No one was looking after me, either. It was sad and hard for me. I know that my sister called me and said, ‘Do you know who I talked to recently? Beverly Kenney’s sister.’ Somehow my sister met up with her. I didn’t even know she had a sister. My sister said, ‘I talked to Beverly Kenney’s sister. She was kind of rude. She said, ‘Well, everyone abandoned Beverly when she needed them, including your sister. And she loved Millie.’ I felt guilty for a while. It was terrible, but it made me think, Well, what the hell was she going through that I didn’t know about? She never shared it.”

‘Surrey With the Fringe on Top,’ Beverly’s demo of the Rodgers & Hammerstein tune, one of her 1954 Decca demos with pianist Tony Tamburello, including on Snuggled on Your Shoulder. Her studio version of on her debut Roost album, Sings for Johnny Smith (1956).

Bill Reed’s research led him to conclude Beverly Kenney suffered from an undiagnosed bipolar disorder. For want of a lithium pill, he says, she is no longer with us. “I’ve seen people in my family who were completely ‘round the bend and there was no possibility of them ever coming back,” he says, “then they pop a couple of lithium tablets and they’re fine. I had someone in my family who was like that.”

At the end, the picture of Beverly Kenney is one of someone completely alone–or feeling completely alone–in the world, and in crisis. She seems to have had no support system at all, but then her reticence at revealing her problems to others mitigated against her few friends rallying around her. According to Bill Reed, she was also completely estranged from her family in New Jersey, owing to her parents’ dim view of her career and lifestyle. “They disapproved of the way she was living her life,” Reed says. “They were kind of hard-core Catholics. The irony of it is that there are a couple of the younger members of the family–nieces and nephews–who are incredibly proud of the fact that their aunt was Beverly Kenney.”

A Kenney family member who emailed Reed in 2007 revealed that the family matriarch forbid other family members from talking about Beverly, and that their silence remained in effect because they felt “betrayed” by Jonathan Schwartz, whose GQ story, the correspondent told Reed, contained “both factual inaccuracies and hurtful insinuations. It now seems to them that maybe it is better to keep silent again.” However, this same correspondent did suggest that Beverly was suffering from biologically based depression and needed but “a situational trigger to push her over the edge.” What that trigger might have been will remain a mystery: in the weeks before her fatal overdose, Beverly was writing intense, emotional letters to her mother, but her mother destroyed all the letters without revealing their contents to anyone. With that went any definitive answers to the mysteries of Beverly Kenney’s tormented inner life, her insecurities, the depth of her despair, perhaps even her joys.

All that remains is speculation over the downward spiral culminating in Beverly alone in her room at the University Residence Club, dead on the floor “with pills scattered about,” as the Times obit reported. Without discounting the undiagnosed bipolar disorder theory, Bill Reed feels Beverly’s despair over the state of her career may well have been overwhelming. He reflects on one of the two video clips he saw of her, when she appeared on The Steve Allen Show and discussed with him her song “I Hate Rock and Roll.”

“I think she’s trying to be a little bit politic and diplomatic, because [Steve Allen] asks her, ‘Do you really hate rock and roll that much?’ And she kind of took the Fifth. She said, ‘No, no, no, not really.’ But in point of fact I think she probably was being sincere. She was probably the pluperfect example of the very first major singer who came along just five seconds too late. I write a lot about what I call the tsunami of rock and roll that just came and blew everything away. I’m always at pains to say I love rock and roll, but it really drove everything out, just completely blew everything away. So when Beverly died, she was totally broke and was still being partially taken care of by Mort, although they were no longer lovers, were no longer living together. She had no money.”

‘Somewhere Along the Way,’ written by Sammy Gallop and Kurt Adams, conducted by Charles Albertine, recorded by Beverly Kenney for her Born to Blue album (1959)

Add to this Reed’s distinct memory of the critics turning on her “for clearly no reason. Critics were savage with her. I don’t know what that was about. It doesn’t really mean anything. There wasn’t any difference in the quality of the records. I mean they were kind of fierce. It was almost like there was a planned assault on her. I will tell you this: Mort Lowenstein describes Beverly Kenney as being like a character out of Cornelius Otis Skinner’s ‘Our Hearts Were Young and Gay’–this young, happy, Greenwich Village girl, smelling the roses, happy go lucky, until one night she attempted suicide in his bathroom without warning. And Millie Perkins, her best friend, said she had never seen her remotely depressed. I’m absolutely certain that what these people are saying is true. Everyone else I’ve talked to–everyone else–describes her as ‘morose,’ almost to the point of hostility. So I don’t know; I believe both versions. I don’t know a lot about bipolar disorders but perhaps they can choose to be the way they are depending on who they’re with. Maybe if they trust somebody or know them, the depression doesn’t set it; I don’t know.”

In a followup email query, still trying to probe the mystery of Beverly Kenney’s demise, I asked Reed why, with all the great press (at least early on), she gained no more professional traction than she did, to where she could work better paying gigs at upper tier venues, or in Vegas.

He replied: “It is a mystery why she couldn’t have made more professional inroads. Beverly had decent management, Ivan Mogull, who went on to much bigger things in the music business as a publisher and producer. But one does get the overall feeling that Beverly lacked the necessary proactive people skills to make necessary professional contacts. From the few surviving reviews of her live performances, I sense she was an engaging enough performer. But offstage, I have only come across two individuals—Mort Lowenstein and Millie Perkins—who paint a picture of someone who was, oh, fun to be with. All other quotes I gleaned were along the lines of ‘kept to herself,’ ‘never really got to know her,’ ‘sad,’ etc. That old, undiagnosed debbil bipolar disorder? Also, from the lack of stories about her that appeared in the press, either by choice, or, most likely, by dint of low finances, I do not detect the fine touch of a publicist so necessary for a performer just starting out. Which is something that small labels like Roost could most definitely not afford. By the time Beverly went to Decca, she was with a label that did have a publicity staff. But maybe they were too busy with the likes of the Kalin Twins, Bill Haley, et al.

“I noticed recently that in all of her later bios, she shaved approximately four years off her actual age. Maybe a desperate attempt not to seem like an old lady in a black dress singing songs from the before time.”

‘I Never Has Seen Snow,’ written by Harold Arlen and Truman Capote and issued on Beverly Kenney’s With Jimmy Jones and the Basie-Ites album (1957).

Speculation upon speculation. Despair begetting tragedy. Questions leading to answers leading to nowhere. To study the many looks of Beverly Kenney as depicted in photographs, or to be enthralled by the vitality of her voice, whether in lament or in joy, is to be left pursuing the elusive grail of the enigma incarnate: Why?

“Beverly was one of a kind, a truly enchanting person, and I choose that word carefully,” Mort Lowenstein reflects at the end of his memoir. “Now, many, many years later, I look at her picture on the CD covers, put on the stereo and once again hear her sweet, innocent voice. And try to think only of the good times.”

Let me tell you about the way she looked, the way she’d act, and the color of her hair. Her voice was soft and cool. Her eyes were clear and bright.

But she’s not there

***

Jonathan Schwartz’s GQ article from November 1992, “Girl Singer: Beverly Kenney lived the jazz life and loved it. But she came undone,” is no longer available online.

Bill Reed’s liner notes for the SSJ Records’ Lonely and Blue Beverly Kenney collection are posted at his website http://chilledairtext.blogspot.com/. These include some of his research into the artist’s life and death.

The v1 version of this story first appeared in The Bluegrass Special.com’s April 2011 issue. It appears here in its latest update, v3.