John McCutcheon: ‘That pesky virus kind of put a kink in the notion of gathering a bunch of my pals and going into a windowless recording studio for days on end.’ (Photo: Irene Young)

By David McGee

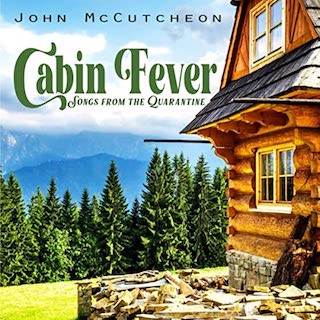

CABIN FEVER

CABIN FEVER

John McCutcheon

Back in mid-March, John McCutcheon found he wasn’t feeling tip-top. He was newly returned from an Australian tour and stepping into a burgeoning public health crisis in his native land. Being an informed citizen and aware of what was unfolding, he retreated to his North Georgia cabin to isolate as a means of protecting his wife and elderly mother-in-law. Over the course of the next three weeks, with not much else to do besides read, write and chat with friends, the prolific folk singer-songwriter produced 18 new songs. These superseded the 30-plus new songs he had written for an album he was planning to record with some high-profile roots stalwarts such as fiddler Stuart Duncan. “That pesky virus kind of put a kink in the notion of gathering a bunch of my pals and going into a windowless recording studio for days on end,” McCutcheon explained in a press release accompanying Cabin Fever. “I mean I love these folks, but…”

‘Front Line,’ John McCutcheon’s tribute to front line workers in the pandemic, from Cabin Fever

‘Sheltered in Place,’ John McCutcheon, from Cabin Fever

Post-quarantine, McCutcheon returned home and to his home studio where, with only his voice, guitar and piano present, he recorded the newest tunes and then sent them to be mixed and mastered by the legendary Bob Dawson at Bias Studios in Springfield, VA. Voila! A new album emerged only a couple of months after the first new song for it had been completed. As McCutcheon has explained, the album is “not exclusively about COVID-19 and its effects, [but] came out of that milieu.” On those terms, it appears to be the most direct album-length response to the pandemic any artist produced in 2020, even if it engages the pandemic obliquely at times. It is also, as far as yours truly can tell, the only album of note to explicitly pay loving tribute to front line workers, whose trials and tribulations in caring for the sick and dying remain, alas, a headline story as this is written in January 2021. In “Front Line,” the album’s starting point, McCutcheon’s warm voice is strong and proud, his guitar accompaniment forceful and assertive, his lyrics empathetic and bold—“On the front line, there’s no place to go/facing the foe where it’s found/on the front line, there’s no time to be scared/pray you’re prepared and just stand your ground…”—in delivering a stirring homage to the bravest of the brave in this fight. But he also turns pandemic language on its ear to flesh out a fuller picture of our times. Though we are now well acquainted with the “shelter in place” directive, for instance, who among us thinks of it in terms of the perennially under siege homeless population? Fashioning a deliberately paced ambience on delicately fingerpicked and strummed passages, McCutcheon coolly speaks in the voice of a homeless man who is unruffled by—and invisible in the midst of–the events swirling around him: “I’m sheltered in place for years/nobody’s know that I’m here/I’m one of the many who just disappears/I’ve sheltered in place for years…” At least McCutcheon can find a smidgen of humor in the pandemic’s effect on modern love: in “Six Feet Away” (do you see it coming?), he recounts taking his “hound” out for a walk one evening (“two souls on a leash”) and by chance making a love connection from afar—“as homeward we steered, there she appeared/and I fell in love from six feet away…two people, two yards, to have not to hold/she held me complete in her sway/I wanted so much but forbidden to touch/so I loved her from six feet away.” That “hound” figures in another lighthearted moment, as McCutcheon describes the canine’s blissful ignorance of all else but his own needs in “My Dog Talking Blues” (“C’mon now, it’s time to scratch my ear/now, now do the other one/and a belly rub would sure be nice/when you are finally done”). On a bittersweet note—a note that in another, more placid era might be heard as something closer to the hymn it sounds like here with McCutcheon’s thoughtful vocal backed solely by his soft, spare piano—the artist muses tenderly on how the world ahead might appear in “One Hundred Years”: “One hundred years from now/in our great-great-grandchildren’s time/will it bear any resemblance to this world of mine/this place of boundless beauty, wonders bright and bold/I can’t possibly imagine what the time ahead might hold…” Isn’t that where we are? Adrift and disconnected from the shape of things to come even while hoping the world will be a better place for those in generations yet unborn who inherit what we’ve wrought in our day?

‘One Hundred Years,’ John McCutcheon, from Cabin Fever

‘Six Feet Away,’ John McCutcheon, from Cabin Fever

As for another aspect of our annus horribilis, McCutcheon pays tribute to the late John Prine, lost to COVID-19 last year, in a beautiful appraisal of the latter’s singular art, of songs “so complex in their simplicity, so honest and so true/just what every writer wished that they could do,” before ascending to a chorus guaranteed to produce a misty-eyed state in a listener engaged at all with Prine’s work, to wit: “There’s an angel from Montgomery that’s finally taken wing/and a place up there called Paradise/where even Sam Stone sings/all the losers, lovers, loners gather around the throne in a mighty choir/to welcome John Prine home…”

‘The Night John Prine Died,’ a live solo acoustic version by John McCutcheon. The recorded version if featured on Cabin Fever.

There’s an understood guideline among music scribes to lean less on lyrics in a review and more on ideas advanced in the songs, but McCutcheon’s language here is simply too captivating to ignore—complex in its simplicity, so honest and so true, if you will—given the characters he creates, the scenes he describes and in its explicit connection to the here and now (in the John Prine song he mentions hearing of Prine’s passing via a friend’s “tearful text” and how he could “feel his sorrow on the screen”—don’t think I’ve ever quite thought of it that way). Cabin Fever is most assuredly a vivid product of its time, but it is also timeless in the knowing way it contemplates isolation, connection, finding meaning in the quotidian and treasuring humanity in all its manifestations. It’s built to last, and so it will.

Cabin Fever is available as a download at the artist’s website for prices ranging from $0 to $500, according to what the purchaser can afford or wants to contribute; the album is also available in mp3 form from Amazon for $9.49.