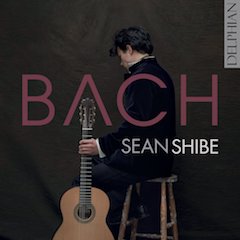

‘Sean Shibe’s Bach has alovely clarity and sense of structure to it, along with his own innate sense of the elegant in the playing’

By Robert Hugill

BACH

BACH

Lute Suite in E minor, Partita in C minor, Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E flat major

Sean Shibe

Delphian

Bach’s relationship to the lute is somewhat tantalizing. We know that when he died, he possessed one, and that throughout his life he used the lute as one of the instruments to introduce interesting sonorities into pieces. He was familiar with lutenists, and as late as 1740 the Dresden court lutenist, Sylvius Leopold Weiss visited Bach’s house in Leipzig. But if Bach played the instrument, it was probably not with great facility and when Bach wrote for it, he used conventional notation rather than lute tablature.

A modern lautenwerk (lute-harpsichord) of the type Bach may have played

And over Bach’s works for solo lute there hangs the suggestion that he wrote them for a lautenwerk, a lute-harpsichord (a keyboard instrument strung with gut strings). Frustratingly, no examples of the instrument survive from the 18th century, but it has been reconstructed. Back in 1715 in Weimar, one of Bach’s employers, the Duke of Saxe-Weimar, acquired a lautenwerk from one of Bach’s cousins through Bach’s good offices, and Bach would have one made for himself in 1740. But Bach used to perform the solo violin works on keyboard, and that he might have used a lautenwerk to play a Lute Suite, does not prevent him having written it for a lutenist.

Part of the problem is that we know Bach’s music for the early lute pieces via other people’s copies, but we don’t have Bach’s original. All we have to go on are reports of him playing the lautenwerk, and mentions of the lautenwerk on later manuscripts in later hands. All very intriguing. Perhaps Bach did write in lute tablature, for lutenists, whilst keeping the music in conventional notation for himself and pupils and what we know is the result of pure serendipity?

Bach, Lute Suite in E minor, Sean Shibe, from his new album, Bach

Then there is the issue of keys: the Baroque lute tended to be in D minor whilst Bach’s Lute Suite BWV 996 is in E minor. The music was popular; many copies (in various keys) of the Partita in C minor BWV 997 survive, for instance. Against this is that the textures of the pieces work well on the lute. Commentators remain divided, but this is terrific music and deserves to be heard. On his new Delphian album, Sean Shibe plays three of Bach’s lute works in the modern classical guitar, the Lute Suite in E minor, BWV 996, the Partita in C minor BWV 997 and the Prelude, Fugue and Allegro BWV 998.

We start with the Lute Suite in E minor, one of Bach’s earliest surviving chamber works and his earliest for lute. It was probably written in Weimar (where Bach worked at the Ducal court) between 1712 and 1717. It has six compact movements in the classic format of Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Bouree and Gigue, and is quite light and entertaining, despite the inclusion of a Pietist hymn in the Prelude; you could imagine it being played at the Ducal court.

Shibe’s tone is warm and clear (if we look at the session photo of Shibe, all bundled up, and note that the venue was Crichton Collegiate Church in mid-December, this warmth is all the more remarkable). He plays fluidly and lightly, yet throughout the disc I was impressed by the way the different contrapuntal lines of the music emerged in his interpretations.

Bach, Partita in C minor BWV 997 (Development), Sean Shibe, from Bach

The faster movements, such as the Allemande, are graceful and flowing, whilst the Courante has a delightful sense of rhythm. They clearly have their origins in dance music without being explicitly so and always with a nice sense of rubato. By contrast, the Sarabande sings soulfully in its melancholy, followed by the delightfully perky Bouree and a surprisingly complex textured Gigue.

The structure is always clear, yet Shibe’s approach does not feel like an academic demonstration (“here is the fugue subject, here the counter-subject,” etc.), but the act of a real musician. You enjoy both the structure and the music itself. It helps that Shibe plays with a wide range of color. In this, his approach is modern: he is not trying to emulate the Baroque lute on a modern guitar, but to bring out the music’s qualities in the most affecting way possible.

Shibe follows this early work with a late one, dating from around 1740, the Partita in C Minor BWV 997. This work has a somewhat complex history, and may have begun as a small piece and been added to; commentators cannot agree, and we don’t have the autograph. Quite free in structure, it’s comprised of Prelude, Fugue, Sarabande, Gigue and Double.

We are in a more thoughtful world here, though Shibe continues to delight with the fluidity of rhythm and the sense that dance measures were still at the back of Bach’s mind. Shibe’s account of the Fugue is superb in the way he combines clarity in the fugal lines with a lovely feeling of musical flow. The way this movement dances is a long way from academic, and the following Sarabande, despite the music’s complexity, has an expressive elegance to it. The Gigue combines a lovely sway to the rhythm with clarity of texture and a sense of the music’s delight, with a positively exciting Double to finish.

A BBC Radio interview introducing New Generation Artist Sean Shibe

Finally, we come to a work of which an autograph exists, dated 1740-41 and with the superscription, Prelude pour la Luth. ò Cembal. par J. S. Bach; alas, we are really none the wiser about what Bach intended. The Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E flat major, BWV 998 is one of the works that most probably was written for the lautenwerk. The work has a soberness or sobriety that we associate with Bach organ music, yet here offered with the fluid textures of the guitar. Bach manages to make the fugue into a remarkable exercise in virtuosity without losing any of the academic rigor, whilst Shibe adds to this a lovely sense of color and line. And things come to a real virtuoso climax with the lively Allegro. This was a performance I never really wanted to end.

Bach was constantly reinventing his music on other instruments, and on this disc Sean Shibe gives us a masterly and elegant demonstration of how suited it is to classical guitar. Shibe’s Bach has a lovely clarity and sense of structure to it, along with his own innate sense of the elegant in the playing. My only real complaint is that at 46 minutes, the disc is rather short, and it seems a shame that the program could not have run to one of Bach’s other works for lute.

Published at Planet Hugill on 27 May 2020, published here with permission. Robert Hugill is a singer, composer, journalist, lover of opera and all things Handel. To receive Robert’s lively “This month on Planet Hugill” e-newsletter, sign up on his Mailing List. (Robert Hugill photo by Robert Piwko)

Published at Planet Hugill on 27 May 2020, published here with permission. Robert Hugill is a singer, composer, journalist, lover of opera and all things Handel. To receive Robert’s lively “This month on Planet Hugill” e-newsletter, sign up on his Mailing List. (Robert Hugill photo by Robert Piwko)