‘Little Richard is very dynamic, completely uninhibited, unpredictable, wild’ –Art Rupe, founder of Specialty Records

A Listener’s Guide to Little Richard

By David McGee

On May 9, Richard Penniman died at the age of 87 at his home in Tullahoma, TN. Cause of death was bone cancer. As Little Richard, the Macon, Georgia-native seemingly came out of nowhere in 1955 after being signed to Art Rupe’s Specialty label in Los Angeles, and took the nascent rock ‘n’ roll world by storm with his debut single, “Tutti Frutti.” Of course he didn’t come out of nowhere. By the time his demos reached Art Rupe’s desk, Richard, going on 25, had been performing since his early teens, in minstrel shows, clubs, bars, Army bases and numerous venues around Atlanta. He was polished and wild—R&B singer Billy Wright became a fashion and professional role model for him, urging Richard to adopt a pompadour hair style like Wright’s, sport a pencil moustache, wear pancake makeup and flashy stage duds. During a brief stint with RCA Records (he recorded eight sides before being dropped, with one, “Every Hour,” becoming a hit single in Georgia), he met and fell under the sway of the flamboyant gay black singer-pianist Eskew Reeder Jr., known professionally as Esquerita (and/or The Magnificent Malochi), whose outlandish, uninhibited performance and piano style young Penniman further perfected as he developed his Little Richard persona (the name by which the world would come to know him came by way orchestra leader Buster Brown, in whose band Richard worked briefly in 1950). A short-lived tenure—again, only eight sides recorded—with Peacock ended when Richard voiced complaints about his pay to label owner Don Robey, prompting Robey to knock Richard cold during scuffle, sending the musician back to Macon, and a dishwashing job. At the urging of Specialty artist Lloyd Price, Richard sent some sonically challenged demos to Art Rupe. Less impressed with the demos than with Richard’s persistence in calling, and calling, and calling, Rupe finally gave the demos another listen and signed the artist. On September 14, 1955, at J&M Studio in New Orleans, Richard, backed by members of Dave Bartholomew’s seasoned band, cut “Tutti Frutti,” a hard driving novelty tune he had written with Dorothy Labostrie (or rather revised by Labostrie, who toned down the suggestive lyrics Richard had penned), produced by Bumps Blackwell, and the Georgia Peach was off and running, looking back only briefly when he abandoned rock ‘n’ roll for the ministry at the height of his ‘50s fame.

Little Richards’ catalogue is extensive and confusing, but it is possible to pinpoint the essential gems out of all the different configurations in which the catalogue now appears. The albums considered in this Listener’s Guide offer a full snapshot of the Quasar of Rock’s musical journey, which reached its height in the ‘50s but continued to produce stirring recordings into the ‘70s and even sporadically thereafter.

The Specialty Sessions box set

At various times over the years, and often without prompting, Richard referred to himself as “the originator, the instigator, the facilitator” of rock ‘n’ roll. To varying degrees he’s right on all counts. Rock ‘n’ roll became a musical and cultural force in 1956, with the electrifying emergence of Elvis Presley into the mainstream with “Heartbreak Hotel.” But by the time the post-War teen culture was coalescing around “Heartbreak Hotel” and Carl Perkins’s “Blue Suede Shoes,” Little Richard’s first Specialty single, the riotous “Tutti Frutti,” released in 1955, was already nearing the end of its pop chart run, having topped out at Number 17 (it was outdone by Pat Boone’s milquetoast cover, which rose to #12 before stalling), setting the stage for his next full-bore rhythmic assault, “Long Tall Sally,” which was released in April 1956 and stayed on the charts for three months (and was covered by Presley, along with two other Little Richard songs, on his second RCA album). In a two-year period dating from September 1955 to October 1957, Penniman recorded an Olympian body of work for Art Rupe’s Los Angeles-based Specialty label—in addition to the above-named hits, his resume includes “Rip It Up,” “Keep A-Knockin’,” “Lucille,” “Jenny Jenny,” “Good Golly Miss Molly,” and “Ready Teddy”—that not only stood with the best music made by Presley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Fats Domino but reached across time and the Atlantic Ocean to have a profound influence on the British artists who would revitalize rock ‘n’ roll come 1964, especially Messrs. Lennon and McCartney of The Beatles.

From Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), Little Richard performs his first Specialty hit, ‘Tutti Frutti.’ Introduction by Alan Freed.

“I was looking for a singer like B.B. King, who was very popular. Frankly, when I got this…at first we didn’t listen to the tape right away. Bumps, who was supposedly screening the tapes, apparently didn’t think much of it, and I can understand why. It was a scratchy tape, it was poorly recorded, it wasn’t a typical good audition tape. And so, if it hadn’t been for Richard’s persistence and aggression, we would never have signed Little Richard. He just kept calling us–from a different town, I’d be getting calls from him. Finally I said, ‘Find that tape,’ and we found it, we listened to it, let’s sign this guy, he sounds like B.B. King to me.’ But of course he isn’t B.B. King.” –Specialty founder Art Rupe, from the interview by Pete Frame included on the reissued Here’s Little Richard.

But Little Richard didn’t arrive at Specialty a fully formed character (well, maybe offstage and in performance he was, but not on record yet). Born December 5, 1932, in Macon, GA, Penniman was singing and playing piano in church at a young age, even as he was absorbing and incorporating into his own repertoire the blues music he heard on the radio. In his early teens he toured the South with medicine shows and various blues bands, and became an acolyte of some formidable regional blues shouters such as Tommy Brown and Billy Wright (a Savoy recording artist who favored pancake makeup, mascara and a multi-level pompadour, and had as much influence on young Penniman on the style front as he did as a musician). His recording career began in 1951 with some sessions for RCA (available on two now-deleted CDs, Rock Legends: Little Richard/Roy Orbison and Rhino’s Shut Up! A Collection of Rare Tracks [1951-1964]); from there he moved to the Peacock label and recorded solo and with the Tempo Toppers, and appeared uncredited on recordings by Christine Kittrell for the Nashville-based Republic label, before returning to Macon to record, on February 9, 1955, the demos, with an early lineup of his band the Upsetters, that were sent to Art Rupe at the Specialty label in Los Angeles. Those early recordings and the Specialty demos–Penniman originals titled “Baby” (a swinging number in a relaxed mode that was the model for one of his great Specialty B sides, “Miss Ann”) and a solid, midtempo blues ballad titled “All Night Long”)–reveal him to be a forceful vocal personality but not necessarily an original one; in fact, his trilling, nasal tone makes him sound almost exactly like another “Little” artist, namely Little Esther Phillips. Disc one of the absolutely essential three-CD collection The Specialty Sessions includes both of the latter demos as well as some early studio experiments conducted after Rupe signed Penniman in 1955 and sent him to J&M Recording Studios in New Orleans. In the Crescent City Penniman was teamed with producer Bumps Blackwell (who was to Little Richard what Dave Bartholomew was to Fats Domino) and the facility’s redoubtable session hands, who included the formidable drummer Earl Palmer, tenor sax man Lee Allen, the exuberant Professor Longhair-influenced piano pounder Huey Smith, Alvin Tyler on baritone sax and Justin Adams on guitar, among other stalwarts. (Penniman is no slacker on the piano, but he played in only one key; on the Specialty recordings, Blackwell used not only Huey Smith, but little-known New Orleans session pianists Melvin Dowden and Edward Frank on the 88s.) Over the course of these sessions, held on September 14 and 15, 1955, Penniman’s own voice began to emerge and that exciting development can be heard aborning on a tender original ballad, “Wonderin’,” and even more dramatically on a brisk treatment of Leiber-Stoller’s jump blues, “Kansas City,” which would undergo a rather breathtaking transformation later in the year, in a November 29 session that also yielded early, rather stilted versions of “Long Tall Sally.” During a break in that November 29 date, Penniman was fooling around with the verses to a bawdy novelty number he performed live, “Tutti Frutti, Good Booty,” when Blackwell suggested the band do a take of the song—after he brought in Dorothy LaBostrie, a young songwriter who had been trying to place some material with Blackwell, to do a quick, PG-rated rewrite. Penniman kicked it off by shouting the most elegant nonsense lyrics in rock & roll history—“Wop-boppa-looma-belop-bomp-bomp”—the band came roaring in and Penniman ascended, declaiming the lyrics in a strong, bluesy voice, half speaking, half singing the revised catalogue describing the gals that drive him crazy. In two takes, both on Disc 1 of the Specialty Sessions box set, a monument was sculpted, and the Quasar of Rock was ready to be loosed on an unsuspecting public.

From Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), Little Richard performs ‘Long Tall Sally’

“It was more or less [Dave Bartholomew’s] band. He’d done all the backing for Fats Domino. Matter of fact, that’s why I went to New Orleans; I was a fan of Fats’. And the engineer, Cosimo, set them up quite similar, because they both sat at the piano except in the few instances where Richard didn’t. But both of them sat at the piano and sang, so the mic placement and the balance was quite similar. A lot of it had to do with Little Richard. Fats is almost, compared to Richard, phlegmatic; very plodding, very slow, very–just opposite, Little Richard is very dynamic, completely uninhibited, unpredictable, wild. So the band took on the ambience of the vocalist, the soloist. –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview

The Specialty Sessions documents Little Richard’s entire, wild ride into the rock & roll stratosphere—including not only the abovementioned demos, but alternate takes and unissued sides as well—up to the moment in 1957 when he abandoned rock & roll for the ministry (and gospel music), before returning to rock & roll and Specialty in 1964. Although the latter sessions produced no U.S. hits, it wasn’t for lack of spirit on Little Richard’s part. His “Bama Lama Bama Loo” featured a supremely possessed vocal, and a hot guitar solo to boot, but it found an audience only in England, where it was a Top 20 single. Even his pep talk to the band here is entertaining—and indicative of his commitment to the music, as captured on tape and included with the cut on Disc 3. “Your solo, don’t forget your solo now,” he says emphatically to one musician, before letting out with, “Owwwww! Just come in strong! Just go strong! A-and while you’re soloing just keep that steady rhythm just poundin’! Do all your little things—just go mad!” It’s a great moment. Art Rupe continued to release Little Richard recordings he had in the can even after the artist had gone into the ministry, but the pop Top 40 run was at an end by mid-1958, when “Ooh! My Soul” peaked at Number 31. The ledger shows, though, that Penniman was not nearly as dominant a pop singles artist as his peers: he never had a Number One single, his highest chart entry was “Long Tall Sally” at Number Six, and he notched only three Top 10 singles during the Specialty years. No matter—the music and the man made an incalculable impact and his standing among the giants is beyond dispute. Each disc in The Specialty Sessions box contains a liner booklet with notes by Ray Topping that provide background on the arc of Little Richard’s career and on the recordings covered on the disc in question. Session personnel credits are sketchy and only supplied in Topping’s text, but he also made sure to give credit where credit was due when someone stood out on a particular recording. No harm, no foul.

Little Richard, ‘Rip It Up,’ the original Specialty single (1955, #17 pop, #1 R&B)

Elvis’s cover of ‘Rip It Up,’ the lead track on his second RCA album, Elvis (1957), which also includes covers of Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’ and ‘Ready Teddy’

“I don’t know…his story is a good characterization of it. I don’t know the real reason. I suspect the reason was other than what is typical Richard other than what he reveals. But he had found religion, he says. He was in Australia on tour and the Sputnik reached its lowest point in that area, and he saw that as a sign that it was Armageddon, the world was coming to an end. Supposedly he took off all his jewelry and threw ‘em into the water, got saved or converted, and he wouldn’t record the Devil’s music anymore–and he wouldn’t work for the Devil anymore either. (laughs) That was Little Richard. We did everything trying to get him to come back, including withholding his royalties. We said, ‘When you comply with your contract, we’ll comply with yours, the money’s here, it’s yours.’ We ended up having to sue him, he counter-sued, and he went his merry way, and we bought out the balance of his contract. It was very difficult, because Richard could have blown his nose and we could have recorded it and sold it! You know, we had the demand. We put out records I never would have ordinarily put out, including splicing together where the timing on it is atrocious. I can’t stand someone not keeping a beat. Even talking about it bothers me now.” –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview.

As a corollary to the box set, check out Shag On Down By the Union Hall, another Specialty gem that includes alternate takes and demos of some Little Richard essentials among its 24 tracks, along with his engaging, swinging interpretations of standards such as “Baby Face” and “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” four key cuts from his 1964 comeback including “Bama Lama Bama Loo,” the title song for the Jayne Mansfield film “The Girl Can’t Help It,” and even a Royal Crown Hair Dressing commercial. In its own way this disc complements the Specialty Sessions box in allowing us a peek at Little Richard in his creative throes, striving toward the mountaintop. For those looking for the cream of the crop, the hits and best-known songs only, several attractive options are out there. Here’s Little Richard, originally released in 1957 and reissued in 2017 as a deluxe double-CD, superbly annotated set, could well have been titled Greatest Hits—its dozen cuts are strictly prime time in-his-prime Little Richard, including “Tutti Frutti,” “Jenny Jenny,” “Ready Teddy,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Miss Ann,” “Rip It Up,” and “She’s Got It.” The reissued album belongs with Little Richard’s essentials both for its song selection, the inclusion of the two demos that landed Richard his Specialty contract and, arguably most important among the value-added elements, a fascinating nine-minute snippet of a 1997 interview with Art Rupe (who rarely talked to the press), conducted by British music write Pete Frame for a radio documentary yet to see the light of day. As if these features were not enough, the set also includes two vintage videos, screen tests of Richard lip-synching “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” priceless gems both, both endlessly watchable.

Little Richard essentials among its 24 tracks, along with his engaging, swinging interpretations of standards such as “Baby Face” and “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” four key cuts from his 1964 comeback including “Bama Lama Bama Loo,” the title song for the Jayne Mansfield film “The Girl Can’t Help It,” and even a Royal Crown Hair Dressing commercial. In its own way this disc complements the Specialty Sessions box in allowing us a peek at Little Richard in his creative throes, striving toward the mountaintop. For those looking for the cream of the crop, the hits and best-known songs only, several attractive options are out there. Here’s Little Richard, originally released in 1957 and reissued in 2017 as a deluxe double-CD, superbly annotated set, could well have been titled Greatest Hits—its dozen cuts are strictly prime time in-his-prime Little Richard, including “Tutti Frutti,” “Jenny Jenny,” “Ready Teddy,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Miss Ann,” “Rip It Up,” and “She’s Got It.” The reissued album belongs with Little Richard’s essentials both for its song selection, the inclusion of the two demos that landed Richard his Specialty contract and, arguably most important among the value-added elements, a fascinating nine-minute snippet of a 1997 interview with Art Rupe (who rarely talked to the press), conducted by British music write Pete Frame for a radio documentary yet to see the light of day. As if these features were not enough, the set also includes two vintage videos, screen tests of Richard lip-synching “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” priceless gems both, both endlessly watchable.

Little Richard’s original Specialty recording of ‘Jenny, Jenny’ (1957), #10 pop, #2 R&B, included on Here’s Little Richard

The Georgia Peach

His Biggest Hits, originally released in 1959, is explained by its title. The Essential Little Richard, which preceded The Specialty Sessions to the market by five years, in its original incarnation as a double-vinyl set foretold the coming of the box set in including the 1955 Macon demos that earned Penniman his Specialty tryout and 18 other cuts spanning the critical 1955-1957 period; its notes also feature personnel listings otherwise puzzlingly absent from the box set’s liner notes. Released in 1959 by Specialty, after the artist had retired to the ministry, The Fabulous Little Richard features some good, bluesy performances (“Shake a Hand,” “Lonesome and Blue,” “Early One Morning”) as well as a credible take on “Whole Lotta Shakin’” and the boisterous version of “Kansas City/Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” that would become more familiar in the Beatles’ cover version on Beatles VI. Unfortunately, to modernize the recordings Art Rupe dubbed in the Stewart Sisters adding background vocals on a few numbers, in one fell swoop diluting the intensity of Richard’s performances. These are tracks Rupe declined to release while Penniman was rocking and rolling, considering them inferior to the now-classic sides; and though there are some gripping performances among these tracks, Rupe was, from a strictly commercial standpoint, on the money. The Georgia Peach is a recommended latter-day anthology of the great songs, some in alternate versions, with the added bonus of astute liner notes by the always-reliable Billy Vera. The Specialty Sessions is  now going for more than $100 from Amazon sellers, but a more reasonably priced, and superb, alternative is available in Directly From My Heart, a triple-CD collection featuring the cream of the Specialty and Vee-Jay years, with its exceptional remastered sonics (to say Little Richard never sounded as otherworldly possessed and completely incendiary on record as he does here is not a stretch) and an informative booklet to guide listeners through the early years and pinpoint the Vee-Jay recordings on which Hendrix is documented as participating.

now going for more than $100 from Amazon sellers, but a more reasonably priced, and superb, alternative is available in Directly From My Heart, a triple-CD collection featuring the cream of the Specialty and Vee-Jay years, with its exceptional remastered sonics (to say Little Richard never sounded as otherworldly possessed and completely incendiary on record as he does here is not a stretch) and an informative booklet to guide listeners through the early years and pinpoint the Vee-Jay recordings on which Hendrix is documented as participating.

‘God is Real,’ from Little Richard’s 1959 gospel album for the Coral label, wherein he channels Mahalia Jackson

Little Richard’s gospel years are inadequately represented on disc now. After becoming a man of the cloth, he recorded for a number of labels—Coral (1959), Mercury (1961-62), Atlantic (1963), Word (1979) and Warner Bros. (1985-86)–but those sides as a whole are mostly out of print. Fortunately, there is on extant example of the gospel Richard in rare form, namely God Is Real, comprised of the 1959 recordings for Coral. Suffice it to say the man is fully in the spirit here: performances of “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” and “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” indicate how persuasive a servant of God Brother Penniman would have been, had he stayed in the pulpit. But the man is breathing a different kind of fire on these tracks: in “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” his voice is thick and heavy, a baritone, sounding much like Billy Eckstine; on “God is Real,” backed by a rumbling organ, he’s channeling Mahalia Jackson in timbre and phrasing, uncannily so; on “Jesus Walked This Lonesome Valley,” he evokes the sound and style of Elvis on the Hillbilly Cat’s first gospel recordings. Remember Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers? “Milky White Way” finds Richard in Cooke territory. Arguably, only on “Coming Home,” more a preaching performance than a vocal one, does he sound most like Little Richard, even as his delivery evokes the style of firebrand minister Rev. J.M. Gates, a force in the spiritual world from the 1920s through the 1940s whose influence can be heard in…Sam Cooke’s gospel approach. May the circle be unbroken. Nobody ever said Richard Penniman did not possess deep roots.

Little Richard’s gospel years are inadequately represented on disc now. After becoming a man of the cloth, he recorded for a number of labels—Coral (1959), Mercury (1961-62), Atlantic (1963), Word (1979) and Warner Bros. (1985-86)–but those sides as a whole are mostly out of print. Fortunately, there is on extant example of the gospel Richard in rare form, namely God Is Real, comprised of the 1959 recordings for Coral. Suffice it to say the man is fully in the spirit here: performances of “Every Time I Feel the Spirit” and “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” indicate how persuasive a servant of God Brother Penniman would have been, had he stayed in the pulpit. But the man is breathing a different kind of fire on these tracks: in “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” his voice is thick and heavy, a baritone, sounding much like Billy Eckstine; on “God is Real,” backed by a rumbling organ, he’s channeling Mahalia Jackson in timbre and phrasing, uncannily so; on “Jesus Walked This Lonesome Valley,” he evokes the sound and style of Elvis on the Hillbilly Cat’s first gospel recordings. Remember Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers? “Milky White Way” finds Richard in Cooke territory. Arguably, only on “Coming Home,” more a preaching performance than a vocal one, does he sound most like Little Richard, even as his delivery evokes the style of firebrand minister Rev. J.M. Gates, a force in the spiritual world from the 1920s through the 1940s whose influence can be heard in…Sam Cooke’s gospel approach. May the circle be unbroken. Nobody ever said Richard Penniman did not possess deep roots.

From Here’s Little Richard, a solid sender non-single album track, the deep blues of ‘Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave’

One of his first stops post-ministry, and following his aborted return to Specialty in 1964, was Chicago’s Vee-Jay label. Way too much of his output here was in the form of updated versions of his Specialty catalogue, and though the music is still “poundin’,” and Penniman’s vocals are as expressive as ever, there’s not much reason to recommend these discs, except to completists and Jimi Hendrix fans, but the abovementioned Directly from My Heart is the place to go for the original studio recordings. Unfortunately, the two volumes of Vee-Jay recordings issued by Collectables as The Very Best of the Vee-Jay Years, are cheap, bare-bones packages containing no session information and inferior audio quality.

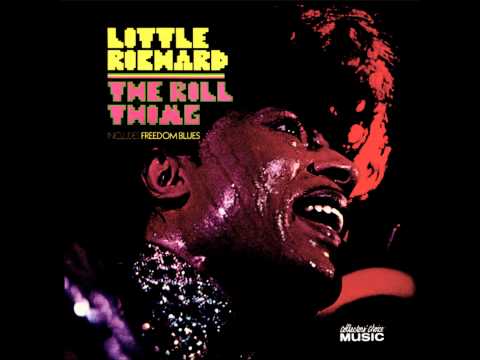

Richard continued recording sporadically through the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, but his last great burst of inspiration came in 1970 when he signed with Warner Bros. and produced himself on the Reprise-issued gem, The Rill Thing. Kicking off with one of his fieriest, funkiest cuts, “Freedom Blues” (co-written by Richard and his early mentor, Esquerita), the Quasar of Rock is in vintage, gospel housewrecking form throughout, his delivery bolstered by a searing sax solo and topical lyrics that gained extra resonance when the single was issued at the height of the Vietnam War. Back in the day, “Freedom Blues” and the driving, southern-fried workout following it, “Greenwood, Mississippi” (a co-write credited to Travis Wammack and Albert Lowe, Jr.), were bold reminders of the special gifts of heart, soul, joy and a free spirit loose on the land that Richard Penniman brought to music as distinctive as that of any American artist’s in the 20th Century. May this good man rest in well-deserved peace, as his music plays on, and on, and on.

1970 when he signed with Warner Bros. and produced himself on the Reprise-issued gem, The Rill Thing. Kicking off with one of his fieriest, funkiest cuts, “Freedom Blues” (co-written by Richard and his early mentor, Esquerita), the Quasar of Rock is in vintage, gospel housewrecking form throughout, his delivery bolstered by a searing sax solo and topical lyrics that gained extra resonance when the single was issued at the height of the Vietnam War. Back in the day, “Freedom Blues” and the driving, southern-fried workout following it, “Greenwood, Mississippi” (a co-write credited to Travis Wammack and Albert Lowe, Jr.), were bold reminders of the special gifts of heart, soul, joy and a free spirit loose on the land that Richard Penniman brought to music as distinctive as that of any American artist’s in the 20th Century. May this good man rest in well-deserved peace, as his music plays on, and on, and on.

‘Freedom Blues,’ Little Richard, from 1970’s The Rill Thing, recorded in Muscle Shoals

Little Richard is a real enigma. If he would have taken direction a little better, if he would have been disciplined, he would have probably been….I don’t know where he could have been. He would have been almost what Frank Sinatra is in the pop field. Little Richard can dominate an audience, he can control an audience, he can upstage any act. He’s unpredictable but he’s got an enormous amount of energy, a tremendous amount of natural talent. I’ve met a lot of performers–Louis Armstrong, Nat Cole, etc.–Little Richard had–has–raw talent. It’s just like an unfinished diamond. I have a lot of admiration for Richard. The real classic of Little Richard would have been his singing old standards, if he had listened to us. You oughta listen to him doing ‘Baby Face.’ He could have put so much feeling doing the old standards that he could be performing today in Las Vegas or anywhere. He was a real interpreter of lyrics, if you could understand them. He’s really excellent. –Art Rupe, from the Pete Frame interview