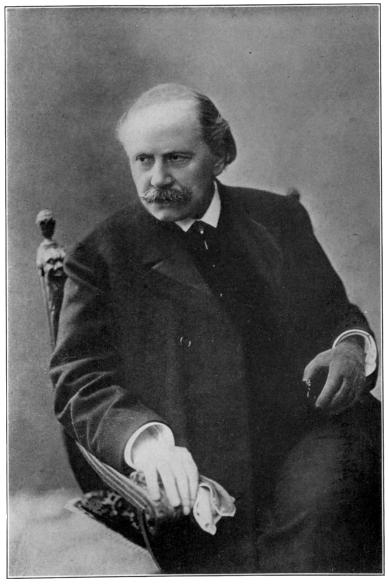

M. Jules Massenet: ‘He had many imitators; he never imitated anyone.’

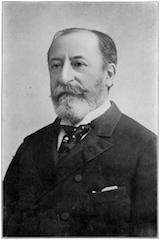

By Camille Saint-Saëns

Translated by Edwin Gile Rich

1919, published by Small, Maynard & Company (Boston)

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (9 October 1835 – 16 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Second Piano Concerto (1868), the First Cello Concerto (1872), Danse macabre (1874), the opera Samson and Delilah (1877), the Third Violin Concerto (1880), the Third (“Organ”) Symphony (1886) and The Carnival of the Animals (1886). In 1919, two years before his death, the composer turned memoirist, reflecting on his era (and those before his time) in Musical Memories, wherein he offered frank assessments of composers and other musical figures of note, often expressing revisionist views of what are now household names in the classical world. In this chapter, he considers the standing of his Romantic era compatriot, Jules Massenet, the leading opera composer in France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (9 October 1835 – 16 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Second Piano Concerto (1868), the First Cello Concerto (1872), Danse macabre (1874), the opera Samson and Delilah (1877), the Third Violin Concerto (1880), the Third (“Organ”) Symphony (1886) and The Carnival of the Animals (1886). In 1919, two years before his death, the composer turned memoirist, reflecting on his era (and those before his time) in Musical Memories, wherein he offered frank assessments of composers and other musical figures of note, often expressing revisionist views of what are now household names in the classical world. In this chapter, he considers the standing of his Romantic era compatriot, Jules Massenet, the leading opera composer in France in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

CHAPTER XIX

JULES MASSENET

Massenet has been praised indiscriminately—sometimes for his numerous and brilliant powers and sometimes =for merits he did not have at all.

I have waited to speak of him until the time when the Académie was ready to replace him,—that is to say, put some one in his place, for great artists are never replaced. Others succeed them with their own individual and different powers, but they do not take their places nevertheless. Malibran has never been replaced, nor Madame Viardot, Madame Carvalho, Talma and Rachel. No one can ever replace Patti, Bartet or Sarah Bernhardt. They could not replace Ingres, Delacroix, Berlioz, or Gounod, and they can never replace Massenet.

It is a question whether he has been accorded his real place. Perhaps his pupils have estimated him at his true worth, but they were grateful for his excellent teaching, and may be rightly suspected of partiality. Others have spoken slightingly of his works and they have applied to him by transposing the words of the celebrated dictum: Saltavit et placuit. He sang and wept, so they sought to deprecate him as if there were something reprehensible in an artist’s pleasing the public. This notion might seem to have some basis in view of the taste that is affected to-day—a predilection for all that is shocking and displeasing in all the arts, including poetry. Sorcières’s epigram—the ugly is beautiful and the beautiful ugly—has become a programme. People are no longer content with merely admiring atrocities, they even speak with contempt of beauties hallowed by time and the admiration of centuries.

The fact remains that Massenet is one of the most brilliant diamonds in our musical crown. No musician has enjoyed so much favor with the public save Auber, whom Massenet did not care for any more than he did for his school, but whom he resembled closely. They were alike in their facility, their amazing fertility, genius, gracefulness, and success. Both composed music which was agreeable to their contemporaries. Both were accused of pandering to their audiences. The answer to this is that both their audiences and the artists had the same tastes and so were in perfect accord.

Itzhak Perlman plays Entr’acte from Massenet’s Thaïs. This performance was recorded at Mr. Perlman’s Carnegie Hall debut, March 5, 1963

To-day the revolutionists are the only ones held in esteem by the critics. Well, it may be a fine thing to despise the mob, to struggle against the current, and to compel the mob by force of genius and energy to follow one despite their resistance. Yet one may be a great artist without doing that.

There was nothing revolutionary about Sebastian Bach with his two hundred and fifty cantatas, which were performed as fast as they were written and which were constantly in demand for important occasions. Handel managed the theater where his operas were produced and his oratorios were sung, and they would have indubitably failed, if he had gone against the accustomed taste of his audiences. Haydn wrote to supply the music for Prince Esterhazy’s chapel; Mozart was forced to write constantly, and Rossini worked for an intolerant public which would not have allowed one of his operas to be played, if the overture did not contain the great crescendo for which he has been so reproached. These were none of them revolutionists, yet they were great musicians.

Another criticism is made against Massenet. He was superficial, they say, and lacked depth. Depth, as we know, is very much the fashion.

It is true that Massenet was not profound, but that is of little consequence. Just as there are many mansions in our Father’s house, so there are many in Apollo’s. Art is vast. The artist has a perfect right to descend to the nethermost depths and to enter into the inner secrets of the soul, but this right is not a duty.

‘Pleurez, mes yeux!’, Maria Callas, from Massenet’s 1885 opera, Le Cid

The artists of Ancient Greece, with all their marvelous works, were not profound. Their marble goddesses were beautiful, and beauty was sufficient.

Our old-time sculptors—Clodion and Coysevox—were not profound; nor were Fragonard, La Tour, nor Marivaux, yet they brought honor to the French school.

All have their value and all are necessary. The rose with its fresh color and its perfume, is, in its way, as precious as the sturdy oak. Art has a place for artists of all kinds, and no one should flatter himself that he is the only one who is capable of covering the entire field of art.

Some, even in treating a familiar subject, have as much dignity as a Roman emperor on his golden throne, but Massenet did not belong to this type. He had charm, attraction and a passionateness that was feverish rather than deep. His melody was wavering and uncertain, oftentimes more a recitative than melody properly so called, and it was entirely his own. It lacks structure and style. Yet how can one resist when he hears Manon at the feet of Des Grieux in the sacristy of Saint-Sulpice, or help being stirred to the depths by such outpourings of love? One cannot reflect or analyze when moved in this way.

‘Le dernier sommeil de la verge’ (‘The Final Sleep of the Virgin’), an orchestral excerpt from the fourth scene of the sacred oratorio ‘La Vierge’ by Jules Massenet. The oratorio is based on the biblical story of the Virgin Mary, and this particular scene depicts the assumption. Performed by Orchestra symphonique de Quebec, conducted by Yoav Talmi, cello by Blair Lofgren

After emotional art comes decadent art. But that is of little consequence. Decadence in art is often far from being artistic deterioration.

Massenet’s music has one great attraction for me and one that is rare in these days—it is gay. And gaiety is frowned upon in modern music. They criticise Haydn and Mozart for their gaiety, and turn away their faces in shame before the exuberant joyousness with which the Ninth Symphony comes to its triumphal close. Long live gloom. Hurrah for boredom! So say our young people. They may live to regret, too late, the lost hours which they might have spent in gaiety.

Massenet’s facility was something prodigious. I have seen him sick in bed, in a most uncomfortable position, and still turning off pages of orchestration, which followed one another with disconcerting speed. Too often such facility engenders laziness, but in his case we know what an enormous amount of work he accomplished. He has been criticised as being too prolific. However, that is a quality which belongs only to a master. The artist who produces little may, if he has ability, be an interesting artist, but he will never be a great one.

Nocturne, from Orchestral Suite No. 1, composed by Jules Massenet, performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jean-Yves Ossonce

In this time of anarchy in art, when all he had to do to conciliate the hostile critics was to array himself with the fauves, Massenet set an example of impeccable writing. He knew how to combine modernism with respect for tradition, and he did this at a time when all he had to do was to trample tradition under foot and be proclaimed a genius. Master of his trade as few have ever been, alive to all its difficulties, possessing the most subtle secrets of its technique, he despised the contortions and exaggerations which simple minds confound with the science of music. He followed out the course he had set for himself without any concern for what they might say about him. He was able to adopt within reason the novelties from abroad and he was clever in assimilating them perfectly, yet he presented the spectacle of a thoroughly French artist whom neither the Lorelei of the Rhine nor the sirens of the Mediterranean could lead astray. He was a virtuoso of the orchestra, yet he never sacrificed the voices for the instruments, nor did he sacrifice orchestral color for the voices. Finally, he had the greatest gift of all, that of life, a gift which cannot be defined, but which the public always recognizes and which assures the success of works far inferior to his.

Visions, a symphonic poem written by Massenet in 1891 but never published. This recording is by the Orchestra Philharmonique de L’Etat de Rhenanie-Palatinet

Much has been said about the friendship between us—a notion based solely on the demonstrations he showered on me in public—and in public alone. He might have had my friendship, if he had wanted it, and it would have been a devoted friendship, but he did not want it. He told—what I never told—how I got one of his works presented at Weimar, where Samson had just been given. What he did not tell was the icy reception he gave me when I brought the news and when I expected an entirely different sort of a reception. From that day on I never intervened again, and I was content to rejoice in his success without expecting any reciprocity on his part, which I knew to be impossible after a confession he made to me one day. My friends and companions in arms were Bizet, Guiraud and Delibes; Massenet was a rival. His high opinion of me, therefore, was the more valuable when he did me the honor of recommending his pupils to study my works. I have brought up this question only to make clear that when I proclaim his great musical importance, I am guided solely by my artistic conscience and that my sincerity cannot be suspected. One word more. Massenet had many imitators; he never imitated anyone.