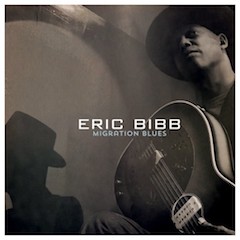

Eric Bibb (with a guitar previously owned by Bukka White): Ambassador without portfolio for an America he wants to be better

MIGRATION BLUES

Eric Bibb

Stony Plain Records

Eric Bibb’s career spans five decades and 37 albums. During that time this son of folk singing activist Leon Bibb and nephew of the Modern Jazz Quartet’s towering composer/pianist John Lewis; who in his formative youth gained much in the way of perspective of the musical and social sort from Bibb household guests such as Odetta, Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson; who moved to Europe in 1970 and still lives in Sweden, where he’s gained perhaps a deeper perspective on his native land than he might have had he stayed here all those years…during this passage of years and social movements and shifting political sands, Eric Bibb has become an ambassador without portfolio for an America he wants to be better. Expat though he may be, Bibb operates from a position of reminding America to keep fighting for what’s right on a purely human level. Politics complicates this position, especially now with, at best, a crook in the White House who is frighteningly oblivious to history. This Eric Bibb, who will turn 66 this coming August, has in the past few years made the best music of his life, and in his new Migration Blues he has also made the most important music of his life.

‘Prayin’ for Shore,’ Eric Bibb, from Migration Blues

‘Refugee Moan,’ Eric Bibb, from Migration Blues

Naturally, with a title such as Migration Blues, the new album is surely centered on the immigration issue now roiling our country, right? Well, yes and no. Certainly yes in the stark ambience (created by the subdued, minimalist embroidery of Bibb’s guitar and contrabass guitar, Michael Jerome Browne’s acoustic 12-string guitar and JJ Milteau’s harmonica) of “Prayin’ for Shore,” wherein a narrator, speaking from the desperation of “a leaky boat/somewhere on the sea/tryin’ to get away from the war,” contemplates what awaits him and his fellow refugees when they make land: “Might be an angry crowd, shakin’ fists in the air/Might be people reachin’ out a helpin’ hand…” Certainly yes, in an equally austere atmosphere (Bibb’s acoustic guitar; Browne’s fretless gourd banjo; Milteau’s moaning harmonica) and the quaver in Bibb’s voice in “Refugee Moan” when he sings, ”If there’s a ship gettin’ ready to sail/let me stand at the rail when it pulls from shore/deliver from this place I know/desecrated by the madness of war.”

‘Delta Getaway,’ Eric Bibb, from Migration Blues

But herein Bibb has an equal, and equally cautionary, message to advance. As the artist states elegantly and succinctly at the end of his liner notes: With this album I wanted to encourage us all to keep our minds and hearts wide open to the ongoing plight of refugees everywhere. As history shows, we all come from people who, at some time or another, had to move. Reflect too on a statement he made to the Seattle Times’s Andrew Gilbert back in 2009: “Music is a spiritual tool for survival and very early on I became aware of that connection. The music was first and foremost sustenance. It was also entertainment, but it primarily started out as a way for people to stay in touch with their divine roots and overcome incredibly difficult situations.”

‘Brotherly Love,’ Eric Bibb, from Migration Blues

‘This Land Is Your Land,’ Eric Bibb, from Migration Blues

The key phrases in those two quotes: “refugees everywhere” and “incredibly difficult situations.” The former includes citizens who were here legally, born and raised, and forced to move in order to survive, such as the black man recounting his perilous migration from the bloody Mississippi Delta to Chicago in “Delta Getaway.” Bibb’s driving fingerpicked acoustic riff evokes the moment’s desperation and fear he articulates in lyrics such as “Tell you people/if you dare to hear/it’s a crime an’ a shame/the way we’re livin’ in fear…” Such as the families black and white forced from their homes when local governments claimed their land by dint of eminent domain for the construction of “bomb factories/stretchin’ across three counties,” as Bibb chronicles in “We Had to Move,” a hearty country blues fueled by his own six-string banjo and Milteau’s jaunty harmonica (the music is deceptively jubilant) in a Bibb tune inspired by James Brown’s family saga as reported in James McBride’s book Kill ‘Em and Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul. Such as the young black man in Bibb’s “With a Dolla’ in My Pocket,” who sees his grandfather “die young in Yazoo” and his father working his entire life “to make ends meet,” and lights out for Chicago via Highway 61 at a breaking point when “my pride couldn’t take it/I cursed the boss, I had to run…” for fear of “hangin’ from the trees in the Mississippi sun.” And in what is one of the great under-reported stories at a moment when the President of the United States has made it his mission to demonize Mexican immigrants, the Bibb-Milteau collaboration on “Diego’s Blues,” featuring only Browne’s resonant 12-string acoustic guitar backing Bibb’s swaggering vocal, is told from the perspective of Diego James Petway, son of a Mexico-born mother who settled in the Delta in 1922. When Diego came of age he found work in the Mississippi cotton fields when the Great Migration of blacks to Chicago from the Deep South created a labor shortage–imagine that. Rather than going to Chicago, he dreams of meeting “my kin down in Mexico.” And then there are others of whom nature makes immigrants: witness the narrator of the B.A. Markus-M.J. Browne raw blues “Four Years, No Rain,” whose world has become uninhabitable: “Birds don’t sing/crops, they just won’t grow/gotta leave the only home I’ve ever known.” The Dust Bowl years of the 1930s produced millions of displaced Americans (the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act that created the Works Progress Administration put 8.5 million displaced workers back on the job, and that was just a start) and fueled timeless American hysteria when Los Angeles sent 125 police officers to the Arizona and Oregon borders with orders to keep “undesirables” out of the so-called City of Angels—is it any wonder Nathaniel West’s Los Angeles was a city in flames in Day of the Locust? The songwriters’ answer to this madness is in finding spiritual cover: War in my country/war in my home town/standin’ on the landin’/dreamin’ of my holy ground.

Staying in touch with his divine roots, Bibb offers solace in the optimistic, humanistic message of “Brotherly Love” (“I believe we can save our ship/’though it’s sinkin’/I believe we can change/the way we’ve been thinkin’/an’ before it’s too late, replace fear an’ hate/with brotherly love”); in a quiet, moving take on the full text of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” about which no explanation should be necessary; and in closing with a solemn, heartfelt rendition of the traditional African-American spiritual “Mornin’ Train,” a song of hope and redemption (“all my sins been taken away”) concluding with a simple but earnest assertion, “I’m goin’ home…”

All who wander are not lost.