Yip Harburg at work…

Editor’s Note: In this installment, contributing editor Michael Sigman turns his space over to his friend Ernie Harburg, son of one of the 20th Century’s greatest songwriters, E.Y. Yip Harburg. For Sigman’s Huffington Post colum Ernie has penned a two-part essay explaining how his father inspired him to become a scientist. Ernie has graciously allowed Michael to offer for reprint in Deep Roots.

Note from Michael Sigman: My friend Ernie Harburg and I are both sons of songwriters — in his case, that songwriter was the transcendent genius Yip Harburg, who wrote the lyrics for such gems as “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and all of the lyrics for the Wizard of Oz film and the Broadway hit, Finian’s Rainbow.

Following is a two-part essay in which Ernie–a Senior Research Scientist Emeritus at the University of Michigan Departments of Epidemiology and Psychology with over 85 scientific articles to his credit (and the President of The Yip Harburg Foundation, dedicated to Yip’s vision of social justice)–traces his deep connection with a father whose mind embraced the beauty of both poetry and science.

When I was very young Yip once said to me that I was the “bone of his bone and the flesh of his flesh.” Naturally, I didn’t know then what that meant. Looking back, I think I can now understand it.

Yip began to make his mark on Broadway during the early 1930s. In ’32, when I was just 5 years old, he was working on three shows and writing three classic lyrics when his first wife, the mother of my sister Marge and me, disappeared. She and Yip had been having trouble (Yip’s electrical appliance business had gone bankrupt with the Depression) and one day she just split! She had dropped Marge and me at Yip’s hotel and a bellhop took us to his floor.

AUDIO CLIP: ‘Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?’ by Bing Crosby

We entered a small room where Yip was sitting on a bed and writing on a yellow pad. He was astonished, but, always one to rise to any emergency, he arranged to put us on a trolley over to Greenpoint–or as we used to say in our Brooklyn accents, “Greenpernt”–and left us with his sister Anna, who had five children of her own and a wonderful husband.

Anna and Phil had migrated–separately–from Russia to America and met each other working in a sweatshop on the Lower East Side of New York City. So, Marge and I were raised by Aunt Anna and Uncle Phil, in Greenpernt and later Crown Heights. Yip came in and out of our lives as he went back and forth between Hollywood and New York City.

In 1935, when I was 9, Yip wanted Marge and me to come to Beverly Hills for the summer to be with him in a house he had rented from Lawrence Tibbett, a famous opera singer who had been making films. Lil, our oldest cousin, took us on a train ride. It took five days from New York to Los Angeles and it was like sending Lenin through Germany.

We finally “landed” at Figueroa Station in Los Angeles. I really wanted to get out of the train’s dark little corridor. The porter opened the door, and miraculously there was the deep blue sky, the blazing sun and these crazy palm trees. (There were no palm trees in Brooklyn!) Then, I saw these funny people wearing blazing shirts and sandals and shorts and there was this red brick on the platform. It was fantastic! Mind you, this was a couple of years before a certain character said it, but I said it to myself in my Brooklynese, “Oinie–I got a feeling we ain’t in Brooklyn no more!” We got out on the station and Lil held our hands until her fingers were breaking and we waited until all the people left the station platform. We were the only ones left.

Suddenly, two guys approached us. One had a huge moustache; he was dressed like a cowboy with wide chaparros, a plaid shirt and a big ten-gallon hat. And he had two guns. The guy next to him was a cop or probably a bobby since he had this bobby hat and a baton. They kept coming and said “All right, clear out of here–clear out of here now!”

As they approached us, Lil became very anxious; then the bobby hit her on the butt with a baton and said “Get outta here!” Raised in Brooklyn, she threw herself up and said, “Who do you think you are?” and that was a signal to me to rush out and put my right fist into that cowboy’s paunch. He bent over and went “Ugh!” The hat came off with the moustache and I heard Marge yell, “It’s Yip!” We laughed so hard we all had to sit down.

I can still see Harold Arlen and Yip at Lawrence Tibbett’s piano. Tibbett had a big pool and a backyard orchard with peaches, plums and sapotas; I had never heard of these things! I used to take daily swims in the pool by myself. One day, there was sort of a reverse miracle–there was no sun, there was no blue sky, it was cloudy, it was cool. So many other days I had walked through the living room where Harold was playing the piano and Yip was walking around and around. I never stayed. I had no idea what these guys were doing in there. They talked sporadically and kept playing jots of music, then would exchange soft words–for hours on a daily basis.

Harold Arlen (with dog on lap) and Yip Harburg working on ‘Last Night When We Were Young’

That day, I had got out of the pool and pulled a towel around me. Then I got goose pimples, but not from a chill. It was a sound. I had never heard such a sound before and I stood there listening as Harold played and sang,

Last night when we were young

Love was a star, a song unsung

Life was so new, so real, so right

Ages ago, last night.

Today the world is old,

You flew away and time grew cold.

Where is that star that shone so bright

Ages ago last night?

I was transfixed. Never had I heard or felt anything so gorgeous!

AUDIO CLIP: Harold Arlen’s rendition of ‘Last Night When We Were Young’

Harold Arlen’s father was a cantor. Harold sang the song like a cantor’s chant. Then I realized that’s what those guys were doing in there. Yip and Harold, through their craft, their discipline and their love for each other’s art, had created a magical song! They took Yip’s title, which had a deep truth to it–“Last Night When We Were Young”–and they made something good, beautiful, transcendent…

In my lifetime, I have published more than eighty-five peer-reviewed scientific articles. Each one to me is like that song: I searched for a truth, and formed it in some kind of truthful and beautiful way. There is a goodness that happens when you do that. That moment in my life has never left me. I always get goose pimples when I hear that particular song.

When I was nine I learned a scientific principle from Yip that was so simple and clear that it has never left my inner ear. Beverly Hills is laid out in a kind of a grid structure; in the northern parts there are streets that come together. I remember one of these junctures where about five, six streets converge. One day Yip drove off to the right and I said “Wait a minute, Yip, wait a minute! We should go straight!” And he turned, looked at me and said “What do you mean?” “Well, the last time we went, we went over there.” And he said “I never go the same way twice.” Kazam! And as a researcher, that’s what you have to do. You must never go the same way twice.

Somewhere between the time I was 10 and 12, Yip decided that I should go to camp.

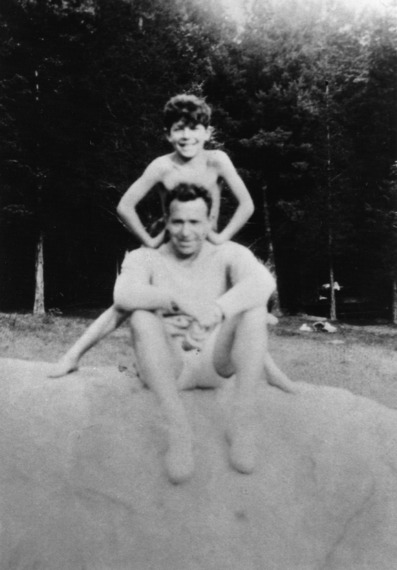

One of my favorite pictures is one of Yip and I when I was at camp in 1937.

You can see we were similar in that Yip was an athlete and I was athletic. Yip told me about one time when he was a pitcher on a sandlot baseball team in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village of New York City around 1910 and they almost got into the city championship!

Then, Yip took me out to the diamond and got a counselor to play catcher and he warmed up a little by throwing the ball. Then he put me behind him and he said, “Now watch this.” He went into a wind-up and he threw the ball. I can still see it; it went fast and then suddenly it curved in to the catcher’s mitt. Yip said, “That is a curve.” And I said “Wow,” and for the next couple hours he showed me how to throw this thing–you grip it by the threads and give it a little twist.

Then he proceeded to tell me about some guy named Bernoulli and his principle in which the ball hit the air and the resistance of the air on the one side spinning faster, then the other side by the twist which made the ball curve. I didn’t know what he was talking about, but it worked! In fact I actually became a pitcher on a sandlot team and I threw a no hitter. I lost one to nothing because the guy in right field dropped the ball. But that curve ball! That curve ball and my father’s explanation really stayed with me.

***

Lyricist Yip Harburg’s Son Ernie: How My Dad Inspired Me To Become a Scientist (Part 2)

This is the conclusion of a two-part essay in which Ernie Harburg–a Senior Research Scientist Emeritus at the University of Michigan Departments of Epidemiology and Psychology with over 85 scientific articles to his credit (and the President of The Yip Harburg Foundation, dedicated to Yip’s vision of social justice)–traces his deep connection with a father whose mind embraced the beauty of poetry and science.

By the ’40s, I had moved from Brooklyn to live in Yip’s new house in Brentwood, CA and attend Beverly Hills High School. This was like leaving Coney Island on a hot day and instantly living in Star Wars! One day Yip took me to a restaurant where there were white tablecloths and sparkling utensils. I had my hand around the glass when the waiter poured the water in, and I noticed that suddenly my fingers were puffed up. I said “Look, Yip. Look at my fingers. What is that all about?” And Yip said, “Well, “the light wave coming from the sun goes through the water and it’s refracted and bent and that’s what causes the distortion, so your perception is non-veridical.” Zing!

Yip had earned a B.S.–not a B.A.–at City College of New York. He was forced to take trigonometry and calculus. His friend Ira refused to do that and dropped out (his brother George had already dropped out of high school). Years later I too got a degree at City College, taking required courses in calculus, physics and chemistry. I too learned about the Bernoulli Principle, the refraction of light, and chemical equilibrium –and I felt attuned to Yip’s scientific mind.

That scientific mind–the knack for problem solving–was essential to Yip’s lyric writing. After all, a lyric is built upon a matrix of melodic notes and chords which starts from an unconscious place–an “artistic key”–a title. The song “April in Paris” actually has only 66 words. The lyricist–in collaboration with the composer–fits these words into a melody with chords to craft a “song.” The team has to be disciplined and creative, rigid and fluid. It’s like explaining your research in an article, or Yip’s Anthem of the Great Depression in two verses:

They used to tell me I was building a dream,

And so I followed the mob.

When there was earth to plough or guns to bear

I was always there, right there on the job.

They used to tell me I was building a dream

With peace and glory ahead.

Why should I be standing in line

Just waiting for bread?

Yip had a scientific mind as well as a poetic one. So when he learned that his son had received a Ph.D., he was flabbergasted. While his mother had given birth to ten children, only four of them survived; but one survivor was his oldest brother Max, a genius who became a professor of physics at age 28! Max was doing research articles about the speed of the earth around the sun and Yip and his parents–my grandparents–were poor first-generation immigrants who didn’t know what to make of it. They were awestruck by his scientific status; but within a month he got cancer and died. Yip adored Max and was impressed by his science; from then on, he became a secular thinker, which in turn influenced deeply my own perspectives about life, the universe and research.

In the Fifties, Yip got hit by the House Un-American Activities Committee anti-communist “witch hunt” and was “blacklisted” from film, radio and TV. We were helped by Yip, who said, “While life is hopeless, hopeless–it’s not serious.”

When I became a research scientist and I had done a large study in Detroit in the Sixties about black-white anger and blood pressure, the New York Times printed that “Dr. Ernest Harburg did blah blah blah.” To Yip this was like Moses coming down with the Commandments. He regarded me almost with reverence as a scientist. And I felt relief that he was off the blacklist and continuing his lyrical activism. The playing field between us was leveled.

By the late Seventies Yip felt mortal for the first time. He had never confronted his death before. We knew he would die soon because he had angina, arrhythmia, intermittent claudication, atherosclerosis and he was taking nitrogen pills and he didn’t want to face up to this.

Yip Harburg

Marge and I and a cousin created the legal basis for two organizations, The Yip Harburg Foundation and the Glocca Morra Music Publishing Company so that the money–royalties from his lyrics–would come in and go to the foundation, which is still dedicated to peace and social justice. We presented the documents to Yip. He was visibly touched and I said, “And so, Yip, we’re giving you a gift of an elegant legacy” (one of his lyrics: “I’ve an elegant legacy waitin’ for ye”). I saw a tear and a twinkle in his eyes, simultaneously. Then he leaned back in his chair and said, “Oh come now, you’re pulling my legacy.”

Months later, in the spring of 1981, Yip did indeed die. And years later, as I was sitting alone at night in the then-newly established Yip Harburg Living Archive at New York University (since moved to Lincoln Center) sorting through old papers, I suddenly came across a note in Yip’s unique handwriting which said “And Ernie! … A Ph.D.!! … I thought he’d be a sand-lot pitcher!!!” I started laughing so loud that I was ejected by the guard!