Producer: Fred Kohlmar

Director: Henry Hathaway

Screenplay: Jay Dratler, Bernard Schoenfeld; Leo Rosten (story)

Cinematography: Joe MacDonald

Art Direction: James Basevi, Leland Fuller

Music: Cyril Mockridge

Film Editing: J. Watson Webb

Running time: 99 minutes (black and white)

CAST

Lucille Ball (Kathleen Stewart)

Clifton Webb (Hardy Cathcart)

William Bendix (Stauffer, alias Fred Foss)

Mark Stevens (Bradford Galt)

Kurt Kreuger (Anthony Jardine)

Cathy Downs (Mari Cathcart)

Reed Hadley (Lt Frank Reeves)

Constance Collier (Mrs. Kingsley)

Eddie Heywood and His Orchestra (Themselves).

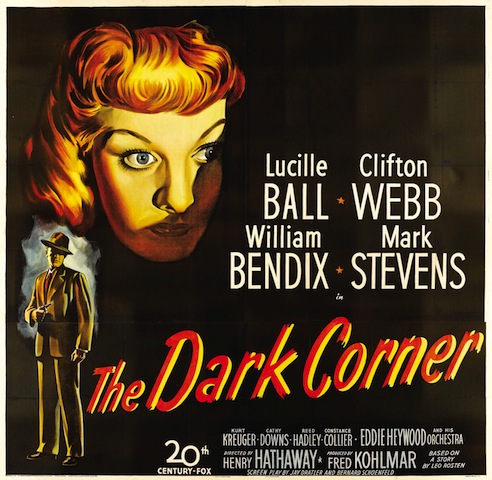

Henry Hathaway’s tight little noir The Dark Corner (1946) is often lost in the critical shuffle of the director’s better-known films from this era–The House on 92nd Street (1945), Kiss of Death (1947) and Call Northside 777 (1948)–but it retains a good reputation among noir cultists as a gem, a sleeper, an unsung classic. While the enthusiasts may be a bit too generous with their praise, the film is nevertheless a worthwhile and even rewarding exercise. The 20th Century Fox production marked Hathaway’s first collaboration with cinematographer Joseph MacDonald, who would later shoot Call Northside 777, the fact-based 14 Hours (1951) and Niagara (1953) for him, as well as My Darling Clementine (1946) for John Ford, The Street With No Name (1947) for William Keighley, Panic in the Streets (1950) for Elia Kazan and Pickup on South Street (1951) for Sam Fuller. True to its title, The Dark Corner is rich in bottomless shadowplay, a persuasive feathering of second unit New York location work and soundstage mock-ups with the odd Los Angeles location doubling for Manhattan and a screenplay rife with pulpy zingers. The script by Jay Dratler (Laura [1944]) and Bernard C. Schoenfeld (Phantom Lady [1944]) seems to send up noir while simultaneously attempting to play the game straight, resulting in a slightly meta-noir experience approximately fifty years ahead of its time.

Dratler and Schoenfeld adapted their screenplay from an original story by humorist Leo Rosen, who used the pseudonym Leonard Q. Ross when his tale was serialized in Good Housekeeping in the summer of 1945. Fox paid $40,000 for the rights and threw around a lot of names before settling on a cast. Fred MacMurray (still hot from Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity [1944]) was discussed for the role of Bradford Galt, a troubled private dick framed for murder, and Ida Lupino (whom Warner Brothers would not release from her commitments there) as his loyal secretary and potential lover. In their places, Fox slotted up-and-comer Mark Stevens (who had been playing uncredited bits only the year before) as Galt and Lucille Ball as Galt’s plucky gal Friday. Ball gets top billing and her presence brings a refreshing lightness to an otherwise dark and even oppressive tale of love, hate, jealousy and greed. Ball had quit RKO for MGM around the time that she married Cuban bandleader Desi Arnaz but the rubber-faced redhead was no happier at Metro. Suing to break her contract, Ball was instead knocked down a pay grade and loaned out to other studios. In later years, the actress was vocal about hating the experience of shooting The Dark Corner. The lion’s share of her resentment was pointed at Henry Hathaway, whose bullying reduced Ball to stuttering–at which point Hathaway had the temerity to accuse her of being inebriated. Stevens and Ball repeated their roles for a radio version of The Dark Corner broadcast on Lux Radio Theatre November 1947.

Lucille Ball with Mark Stevens in The Dark Corner: director Henry Hathaway’s bullying led Lucy to be “vocal about hating the experience of shooting The Dark Corner.’

Clifton Webb’s pivotal role of epicene art collector Hardy Cathcart is modeled on the actor’s immortal turn as Waldo Lydecker in Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), also produced by Daryl F. Zanuck. Zanuck had opposed Preminger’s casting of Webb in the earlier film, partly because Webb had no real film career prior to 1944 and also because he couldn’t accept the fey and fussy stage performer as a heavy. Audiences, however, loved Waldo and the success of Laura ensured that Hardy Cathcart would be supplied with a fund of wry Henry Wotton-isms (“The enjoyment of art is the only remaining ecstasy that is neither illegal nor immoral”) and tart rejoinders. Webb’s withering reprimand to oafish hireling William Bendix (“Stop flicking your ashes on my rug. It’s a genuine Kashan.”) anticipates a similar exchange in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970) a generation later between Mick Jagger’s pretentious ex-rocker and James Fox’s nervous gangster on the lam.

Clearly enjoying a chance to play a non-Nazi for a change is Kurt Kreuger from Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! and Zoltan Korda’s Sahara (both 1943) while perennial narrator Reed Hadley turns up in the flesh throughout The Dark Corner as a good cop with Galt’s best interest at heart.

The New York location doubling as The Cathcart Gallery is recognizable as Manhattan’s Burden Mansion at 7 East 91st Street. The structure’s next-door neighbor on New York City’s “Museum Mile” later starred as the upscale apartment building besieged by Sean Connery’s crew of home breakers in Sidney Lumet’s The Anderson Tapes (1971). –- by Richard Harland Smith at Turner Classic Movies

SELECTED SHORT SUBJECT: ‘THE TALKING MAGPIES’ (1946)

This prototype of the first Heckle and Jeckle cartoon (The Talking Magpies, which became the team’s identifying nickname) premiered in January 1946. The cartoon featured Farmer Al Falfa and his dopey dog, an embryonic version of Dimwit, contending with a gang of magpies that has taken over his house and farm At this point the duo was still unnamed (one of them is addressed as “Maggie” at one point), and had white beaks. While one magpie had a vaguely New York-like accent, the other had no trace of British accent at all—and was female, wearing a ladies hat. This premiere short cast the pair as a noisy husband-and-wife couple looking for a new home. “Listen to the Mockingbird,” which would become their unofficial signature theme, plays over the opening titles. This is one of Farmer Alfalfa’s few appearances in a Technicolor Terrytoon.

All subsequent episodes (beginning with 1946’s The Uninvited Pests) portrayed both characters as males, and featured their now-familiar colors and characterizations. The cartoons were directed on a rotating basis by Connie Rasinski, Eddie Donnelly and Mannie Davis. A five-year production hiatus coincident with Gene Deitch’s tenure as the new Terrytoons producer began in 1955. The characters were later revived by directors Dave Tendlar and Martin Taras, under Deitch’s successor Bill Weiss in 1960. The final episode, Messed Up Movie Makers from longtime studio animators Al Chiarito and George Bakes, was produced in 1966.