Anonymous 4: (from left) Ruth Cunningham, Marsha Genensky, Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, Susan Hellauer. ‘For us, it’s always been about telling a tale of human experience, not necessarily literally but providing context and a dramatic arc for the music,’ says Ms. Hellauer.

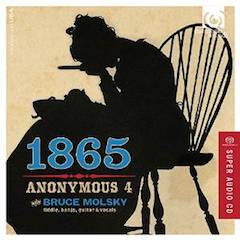

1865

SONGS OF HOPE AND HOME FROM THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

Anonymous 4

Harmonia Mundi

To appraise Anonymous 4’s 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War (marking the 150th anniversary of the War’s end) is to be engaged in a most melancholy task—not, mind you, because the album is lacking in any way. It is, in fact, the first great album of 2015. It is also, alas, the last long player in the great Anonymous 4’s stellar 30-year career. This year and next will see the incomparable quartet making its final concert appearances before disbanding with a catalogue boasting 22 albums and some two million in sales. Although some fine practitioners of early music remain, and there will be others, A4’s achievement as musicologists and as artists is unmatched. To them goes the credit of elevating early music to a level of popularity even they would not have envisioned when they set out on this path; on their journey they have unearthed and preserved many ancient medieval texts otherwise thought lost, including Hungarian Christmas music (as collected on the album A Star In the East) and, most notably, the daring music of the 12th century abbess of many talents, Hildegard von Bingen, which A4 singlehandedly rescued from history’s deepest shadows on The Origin of Fire: Music and Visions of Hildegard von Bingen and thus spurred a full-on Hildegard revival.

A promotional trailer from Harmonia Mundi for Anonymous 4’s 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War

For their final album, these gifted ladies are returning to more contemporary turf—in the context of their history, that is—with an album of songs from the Civil War era. It’s not unfamiliar terrain for A4: 1865 represents the final flowering of an Americana trilogy the group inaugurated in 2004 with American Angels, which did nothing less than reach #1 on Billboard’s chart, followed by 2006’s Gloryland. Known for its precision a cappella arrangements, A4 is here accompanied on 1865 by a true mountain music scholar and multi-instrumentalist, Bruce Molsky. In addition to his empathetic accompaniment on banjo, guitar and fiddle Mr. Molsky also has a couple of memorable lead vocals, on a moving version of Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times Come Again No More,” and a heart tugging one on “Brother Green,” the lyrics being the dying words of a Union soldier (“…for I am shot and bleeding/and I must die, no more to see/my wife and my dear children”). Of her fellow Bronx native, A4’s resident historian, Susan Hallauer (who met Molsky a decade ago when she took banjo lessons from him) notes (in press materials accompanying the review copy of 1865), “Bruce is in the line of Northern folk musicians who went into Appalachia and down South to sit at the feet of great traditional musicians, absorbing the sound and feeling of a previous generation—he’s one of those keepers of a cultural heritage. For me, for all of us, it was a real discovery to find that we could collaborate with a musician who doesn’t read music—but who, playing by ear, is the ultimate musician in so many ways. He’s not a strict traditionalist, never slavish. For him, folk music is always a living thing, and he helped us live in this music. Moreover, he can break hearts every time. The way Bruce sings ‘Brother Green’ on the album—when I her it, I just can’t keep it together.”

From 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War, Stephen Foster’s ‘Hard Times Come Again No More.’ Lead vocal and fiddle, Bruce Molsky, with Anonymous 4

And what does Mr. Molksy support, when he does play? The impeccable beauty the women of A4—Ms. Hellauer, Marsha Genesky, Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek and Ruth Cunningham—bring, solo and ensemble, to songs from the most horrible time in this country’s history. Some of these selections—such as the spiritual “Shall We Gather at the River” (here in a different arrangement than that heard on American Angels) and the aforementioned “Hard Times Come Again No More”—have found a permanent place in old-time music and are still frequently performed and recorded; others have had no life beyond the terrible, anguished moments of their creation. But to hear the plaintive A4 harmonies on the album opening “Weeping, Sad and Lonely” (or “When This Cruel War Is Over”), so delicately rendering those literate, searing lyrics (“If, amid the din of battle/Nobly you should fall/Far away from those who love you/None to hear you call/Who would whisper words of comfort/Who would soothe your pain/Ah! The many cruel fancies/Every in my brain..”) is to feel at least a smidgen of the unquenched pain in which those words were composed. As they have done with medieval polyphony so have they done with American popular and gospel songs: lend them immediacy, a vibrancy, that captures a listener’s heart and makes the lyrics’ message transformative—you will never hear these songs the same way again or ever be touched more vitally by their sentiments: “Let us pause in life’s pleasures, and count its many tears/while we all sup sorrow with the poor; there’s a song that will linger forever in our ears; oh, hard times, come again no more.”

“For us, it’s always been about telling a tale of human experience, not necessarily literally but providing context and a dramatic arc for the music,” says Susan Hellauer. “With 1865 the story is the misery of a long war and the joy at its end, the human tragedies on the battle front and the heartache at home. After all, the story of the Civil War is more than just battles or a peace treaty or the assassination of Lincoln. It’s also about the smaller-scale human emotions, which we recognize because they’re bound up in what it means to be human. These songs carry a lot of weight, even the happy ones. Soldiers would sing some of these songs at night in encampments, then be out killing and dying the next day.”

Henry Tucker: Weeping, Sad and Lonely, or, When this Cruel War is Over

SELECTED TRACK: ‘Weeping, Sad and Lonely’ (or ‘When This Cruel War Is Over’), Anonymous 4, from 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War

Indeed, in the song selections here so many sentiments are expressed not for a North or South victory but simply for it all to end, for families to be reunited in flesh, not in spirit or in Heaven. The quiet around A4’s a cappella rendering of Walter Kittredge’s 1864 subtle anti-war treatise “Tenting On the Old Camp Ground” is positively haunting, never more so than when the ladies come to the heart tugging chorus: “Many are the hearts that are weary tonight/wishing for the war to cease/Many are the hearts looking for the right/to see the dawn of peace/tenting tonight, tenting tonight/tenting on the old camp ground.” That haunting quiet gives way eventually to a spirited, if slightly muted, anticipation of the blessed return, as A4 raises its voices in warm, uplifting harmony over Molsky’s cheerful frailed banjo in “Home Sweet Home,” singing, “An Exile from home, splendor dazzles in vain; oh! Give me my lowly thatched cottage again/the birds singing gaily, that came at my call/give me them, with the peace of mind, dearer than all.” A4’s version is in contrast to the way the song was performed back in the day, as a sentimental ballad that was banned by the Union Army for fear of its lyrics longing for the sanctity and safety of home and family inciting a rash of desertions (the Army of the Confederacy had no such qualms, nor did President Lincoln, who requested it be performed at an 1862 White House concert by opera singer Adelina Patti). The song dates from the 1823 opera Clari, Maid of Milan by American playwright John Howard Payne with a melody by Sir Henry Bishop drawn from an old Italian folk song.

Anonymous: The True Lover’s Farewell

SELECTED TRACK: ‘The True Lover’s Farewell,’ Anonymous 4 (lead vocal: Marsha Genensky), from 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War. This song is the source of the Carter Family’s ‘Storms Are On the Ocean.’

Death being a constant during these violent years, it naturally cropped up in the music of the time. Marsha Genensky’s clarion, wounded soprano, harmonized by Molsky’s baritone, adds even greater poignancy to “The True Lover’s Farewell,” wherein a soldier vows to return to his love even as he anticipates his own demise (Carter Family fans will recognize the source of “Storms Are On the Ocean” here in the verse on which the song’s narrative turns–“And who will shoe your pretty little feet/and who will glove your hand/and who will kiss your red rosy cheek/when you return again”—and later verses A.P. Carter adapted for his own purposes). Equally piercing, with the gentleness of a hymn, Henry Clay Work’s “The Picture On the Wall,” with Molsky’s softly picked acoustic guitar and lead vocal backed by A4’s close, silky harmonies, contemplates the gulf left when loved ones die in battle, “when friends bereft, have only left, a picture on the wall.”

SELECTED TRACK: ‘Aura Lea,’ Anonymous 4 (lead vocal: Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek), in its original incarnation before its 20th century transformation as ‘Love Me Tender.’ From 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War.

Among the pleasant surprises: the beautiful love song “Aura Lea,” with Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek’s delicate, gentle reading supported by Molsky’s acoustic guitar, in its original form, before it inspired “Love Me Tender” and a bravura ballad performance by young Elvis Presley. Also, “Listen to the Mockingbird,” bright, chirpy and galloping, but harboring a melancholy remembrance of a departed lover (“she sleeping in the valley/and the mocking bird is singing where she lies”). As Ms. Genensky notes in the liner booklet: “Some of our songs are still sung today, like ‘Abide With Me’ and ‘Shall We Gather At the River?’ Others, like ‘The Picture on the Wall’ or ‘Southern Soldier Boy,’ are more trapped in time. But even with the ones we think we know, we might not really know them, truly. ‘Tenting On the Old Camp Ground’ was in The Fireside Book of Folk Songs that was on the piano in my house when I was growing up, and I had always thought it was kind of dopey. But once I looked more closely at the words, I realized that it was a brilliant anti-war song with a sentiment much like the anti-war songs from 100 years later in the 1960s, albeit written in a very different style of language. Then there are songs that are still in the air today that we don’t realize came from that time. When we sang ‘Listen To the Mockingbird’ for the first time, Susan knew she recognized it from something else. She later realized that the tune was quoted in the intro to The Three Stooges short films.”

Walter Kittredge: Tenting on the Old Camp Ground

SELECTED TRACK: ‘Tenting On the Old Camp Ground,’ William Kittredge’s subtle anti-war treatise from 1864. Anonymous 4 from 1865: Songs of Hope and Home from the American Civil War

The Civil War continues to produce more literature, more music and more movies exploring its many twists, turns, dramas, fatal tactical errors, brilliant battlefield maneuvers and figures major and minor, Blue and Grey alike. 1865 takes an honored place in this canon, following in the footsteps of 2013’s God Didn’t Choose Sides: Civil War True Stories about Real People, Vol. 1, featuring various artists on the Rural Rhythm label (a Deep Roots Album of the Week, April 11, 2013) and, from the same year, also on Rural Rhythm, Mike Scott & Friends moving, all-instrumental Home Sweet Home: Civil War Era Songs (also a Deep Roots Album of the Week, July 8, 2013). So does Anonymous 4 mark the end of their magnificent, groundbreaking career with an album of songs marking the end of the defining event in American history. It’s quite a note to sign off with, but Marsha Genensky sees it as a most appropriate sign-off. “When we perform medieval music, we’re inviting the audience to come into an intimate space with us,” she says. “Whereas when we perform the Americana music, we’re reaching out to our listeners. We’re performing this Americana material during our final year together, and I have to say that it’s so nice to go out on an open-hearted, extroverted note.”

For more Anonymous 4 coverage, please visit our A4 cover story in this publication’s original incarnation as TheBluegrassSpecial.com, “A-Caroling They Go,” in our December 2010 Christmas issue.

Also, the November 2011 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com features an interview with Susan Hellauer keyed to the release of A4’s Secret Voices: Chant & Polyphony from the Las Huelgas Codex C1300, released in conjunction with the group’s 25th anniversary year. In the interview Ms. Hellauer discusses not only the genesis and evolution of Secret Voices but also reflects on Anonymous 4’s entire career. Click here to visit “A Quarter-Century of Anonymous 4.”

From the two interviews cited above we have pieced together a Q&A with Marsha Genensky and Susan Hellauer as a kind of “exit interview,” focusing on some of the larger themes of A4’s career and modus operandi as opposed to any specific album. Click here to read the interview, “Anonymous 4: The Exit Interview (Sort of).”