“A steak and kidney pie, influenza and a cablegram. There is the triple alliance that is responsible for the whole thing.”

“A steak and kidney pie, influenza and a cablegram. There is the triple alliance that is responsible for the whole thing.”

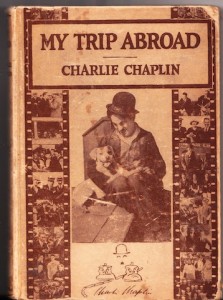

So begins Charlie Chaplin’s My Trip Abroad, a travel memoir charting the actor-director’s semi-spontaneous visit to Europe, published in New York and London by Harper & Brothers in 1922. Fresh off the success of 1921’s The Kid, Chaplin decides to “play hookey” after his seven year stay in Hollywood. He returns to his native Europe as an international superstar, beloved by fans and hounded by reporters. The “triple alliance” of the book’s opening line sends Chaplin on a whirlwind tour through Great Britain, Germany, and France with results ranging from funny to insightful to poignant with no sugarcoating his moods, be they ebullient, weary or annoyed. Though it was still the silent era in film history, the Chaplin voice in My Trip Abroad is true to the complexities of the character he had already made legendary on the silver screen.

In the following excerpt, “The Haunts of My Childhood,” Charlie returns to the neighborhood where he spent his impoverished youth and immediately recognizes that “I am seeing it through other eyes. Age trying to look back through the eyes of youth. A common pursuit, though a futile one.” (My Trip Abroad was published in the U.K. as My Wonderful Visit.)

Charlie as he is to his friends.

VI. THE HAUNTS OF MY CHILDHOOD

I jump into the automobile again and we drive along past Christ Church. There’s Baxter Hall, where we used to see magic-lantern slides for a penny. The forerunner of the movie of today. I see significance in everything around me. You could get a cup of coffee and a piece of cake there and see the Crucifixion of Christ all at the same time.

We are passing the police station. A drear place to youth. Kennington Road is more intimate. It has grown beautiful in its decay. There is something fascinating about it.

Sleepy people seem to be living in the streets more than they used to when I played there. Kennington Baths, the reason for many a day’s hookey. You could go swimming there, second class, for three pence (if you brought your own swimming trunks).

Through Brook Street to the upper Bohemian quarter, where third-rate music-hall artists appear. All the same, a little more decayed, perhaps. And yet it is not just the same. 84

I am seeing it through other eyes. Age trying to look back through the eyes of youth. A common pursuit, though a futile one.

It is bringing home to me that I am a different person. It takes the form of art; it is beautiful. I am very impersonal about it. It is another world, and yet in it I recognise something, as though in a dream.

A first edition of My Trip Abroad features a signed inscription by Charlie on the recto of the frontispiece photograph: “To my dear old pal Billy. Hoping you will have a little fun browsing through this. Charlie Chaplin, Feb. 24th 1922.”

We pass the Kennington “pub,” Kennington Cross, Chester Street, where I used to sleep. The same, but, like its brother landmarks, a bit more dilapidated. There is the old tub outside the stables where I used to wash. The same old tub, a little more twisted.

I tell the driver to pull up again. “Wait a moment.” I do not know why, but I want to get out and walk. An automobile has no place in this setting. I have no particular place to go. I just walk along down Chester Street. Children are playing, lovely children. I see myself among them back there in the past. I wonder if any of them will come back some day and look around enviously at other children.

Somehow they seem different from those children with whom I used to play. Sweeter, more dainty were these little, begrimed kids with their arms entwined around one another’s waists. Others, little girls mostly, sitting on the doorsteps, with dolls, with sewing, all playing at that universal game of “mothers.”

For some reason I feel choking up. As I pass they look up. Frankly and without embarrassment they look at the stranger with their beautiful, kindly eyes. They smile at me. I smile back. Oh, if I could only do something for them. These waifs with scarcely any chance at all.

Now a woman passes with a can of beer. With a white skirt hanging down, trailing at the back. She treads on it. There, she has done it again. I want to shriek with laughter at the joy of being in this same old familiar Kennington. I love it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2PGBGLhLS0

Charlie Chaplin and Edna Purviance in Sunnyside (1919). In My Trip Abroad Charlie calls this 28-minute short for First National Pictures ‘one of my favourite photo plays.’ Written, produced and directed by Charlie Chaplin.

It is all so soft, so musical; there is so much affection in the voices. They seem to talk from their souls. There are the inflections that carry meanings, even if words were not understood. I think of Americans and myself. Our speech is hard, monotonous, except where excitement makes it more noisy.

There is a barber shop where I used to be the lather boy. I wonder if the same old barber is still there? I look. No, he is gone. I see two or three kiddies playing on the porch. Foolish, I give them something. It creates attention. I am about to be discovered.

I leap into the taxi again and ride on. We drive around until I have escaped from the neighbourhood where suspicion has been planted and come to the beginning of Lambeth Walk. I get out and walk along among the crowds.

People are shopping. How lovely the cockneys are! How romantic the figures, how sad, how fascinating! Their lovely eyes. How patient they are! Nothing conscious about them. No affectation, just themselves, their beautifully gay selves, serene in their limitations, perfect in their type.

I am the wrong note in this picture that nature has concentrated here. My clothes are a bit conspicuous in this setting, no matter how unobtrusive my thoughts and actions. Dressed as I am, one never strolls along Lambeth Walk.

I feel the attention I am attracting. I put my handkerchief to my face. People are looking at me, at first slyly, then insistently. Who am I? For a moment I am caught unawares.

A girl comes up—thin, narrow-chested, but with an eagerness in her eyes that lifts her above any physical defects.

“Charlie, don’t you know me?”

Of course I know her. She is all excited, out of breath. I can almost feel her heart thumping with emotion as her narrow chest heaves with her hurried breathing. Her face is ghastly white, a girl about twenty-eight. She has a little girl with her.

Charlie entertaining guests at Hearst Castle in an undated photograph

This girl was a little servant girl who used to wait on us at the cheap lodging-house where I lived. I remembered that she had left in disgrace. There was tragedy in it. But I could detect a certain savage gloriousness in her. She was carrying on with all odds against her. Hers is the supreme battle of our age. May she and all others of her kind meet a kindly fate.

With pent-up feelings we talk about the most commonplace things.

“Well, how are you, Charlie?”

“Fine.” I point to the little girl. “Is she your little girl?”

She says, “Yes.”

That’s all, but there doesn’t seem to be much need of conversation. We just look and smile at each other and we both weave the other’s story hurriedly through our own minds by way of the heart. Perhaps in our weaving we miss a detail or two, but substantially we are right. There is warmth in the renewed acquaintance. I feel that in this moment I know her better than I ever did in the many months I used to see her in the old days. And right now I feel that she is worth knowing.

There’s a crowd gathering. It’s come. I am discovered, with no chance for escape. I give the girl some money to buy something for the child, and hurry on my way. She understands and smiles. Crowds are following. I am discovered in Lambeth Walk.

But they are so charming about it. I walk along and they keep behind at an almost standard distance. I can feel rather than hear their shuffling footsteps as they follow along, getting no closer, losing no ground. It reminds me of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

All these people just about five yards away, all timid, thrilled, excited at hearing my name, but not having the courage to shout it under this spell.

“There he is.” “That’s ‘im.” All in whispers hoarse with excitement and carrying for great distance, but at the same time repressed by the effort of whispering. What manners these cockneys have! The crowds accumulate. I am getting very much concerned. Sooner or later they are going to come up, and I am alone, defenceless. What folly this going out alone, and along Lambeth Walk!

Charlie Chaplin and Edna Purviance share their first on-screen kiss, in The Champion, released March 11, 1915

Eventually I see a bobby, a sergeant—or, rather, I think him one, he looks so immaculate in his uniform. I go to him for protection.

“Do you mind?” I say. “I find I have been discovered. I am Charlie Chaplin. Would you mind seeing me to a taxi?”

“That’s all right, Charlie. These people won’t hurt you. They are the best people in the world. I have been with them for fifteen years.” He speaks with a conviction that makes me feel silly and deservedly rebuked.

I say, “I know it; they are perfectly charming.”

“That’s just it,” he answers. “They are charming and nice.”

They had hesitated to break in upon my solitude, but now, sensing that I have protection, they speak out.

“Hello, Charlie!” “God bless you, Charlie!” “Good luck to you, lad!” As each flings his or her greetings they smile and self-consciously back away into the group, bringing others to the fore for their greeting. All of them have a word—old women, men, children. I am almost overcome with the sincerity of their welcome.

We are moving along and come to a street corner and into Kennington Road again. The crowds continue following as though I were their leader, with nobody daring to approach within a certain radius.

The little cockney children circle around me to get a view from all sides.

Charlie Chaplin in his first professional role as a child performer, as a member of the clog dancing troupe Eight Lancashire Lads

I see myself among them. I, too, had followed celebrities in my time in Kennington. I, too, had pushed, edged, and fought my way to the front rank of crowds, led by curiosity. They are in rags, the same rags, only more ragged.

They are looking into my face and smiling, showing their blackened teeth. Good God! English children’s teeth are terrible! Something can and should be done about it. But their eyes!

Soulful eyes with such a wonderful expression. I see a young girl glance slyly at her beau. What a beautiful look she gives him! I find myself wondering if he is worthy, if he realises the treasure that is his. What a lovely people!

We are waiting. The policeman is busy hailing a taxi. I just stand there self-conscious. Nobody asks any questions. They are content to look. Their steadfast watching is so impressing. I feel small—like a cheat. Their worship does not belong to me. God, if I could only do something for all of them!

But there are too many—too many. Good impulses so often die before this “too many.”

I am in the taxi.

“Good-bye, Charlie! God bless you!” I am on my way.

The taxi is going up Kennington Road along Kennington Park. Kennington Park. How depressing Kennington Park is! How depressing to me are all parks! The loneliness of them. One never goes to a park unless one is lonesome. And lonesomeness is sad. The symbol of sadness, that’s a park.

But I am fascinated now with it. I am lonesome and want to be. I want to commune with myself and the years that are gone. The years that were passed in the shadow of this same Kennington Park. I want to sit on its benches again in spite of their treacherous bleakness, in spite of the drabness.

But I am in a taxi. And taxis move fast. The park is out of sight. Its alluring spell is dismissed with its passing. I did not sit on the bench. We are driving toward Kennington Gate.

Kennington Gate. That has its memories. Sad, sweet, rapidly recurring memories.

‘Twas here, my first appointment with Hetty (Sonny’s sister). How I was dolled up in my little, tight-fitting frock coat, hat, and cane! I was quite the dude as I watched every street car until four o’clock waiting for Hetty to step off, smiling as she saw me waiting.

Charlie and the nymphs from Sunnyside

I get out and stand there for a few moments at Kennington Gate. My taxi driver thinks I am mad. But I am forgetting taxi drivers. I am seeing a lad of nineteen, dressed to the pink, with fluttering heart, waiting, waiting for the moment of the day when he and happiness walked along the road. The road is so alluring now. It beckons for another walk, and as I hear a street car approaching I turn eagerly, for the moment almost expecting to see the same trim Hetty step off, smiling.

The car stops. A couple of men get off. An old woman. Some children. But no Hetty.

Hetty is gone. So is the lad with the frock coat and cane.

Back into the cab, we drive up Brixton Road. We pass Glenshore Mansions—a more prosperous neighbourhood. Glenshore Mansions, which meant a step upward to me, where I had my Turkish carpets and my red lights in the beginning of my prosperity.

We pull up at The Horns for a drink. The same Horns. Used to adjoin the saloon bar. It has changed. Its arrangement is different. I do not recognise the keeper. I feel very much the foreigner now; do not know what to order. I am out of place. There’s a barmaid.

How strange, this lady with the coiffured hair and neat little shirtwaist!

“What can I do for you, sir?”

I am swept off my feet. Impressed. I want to feel very much the foreigner. I find myself acting.

“What have you got?”

She looks surprised.

“Ah, give me ginger beer.” I find myself becoming a little bit affected. I refuse to understand the money—the shillings and the pence. It is thoroughly explained to me as each piece is counted before me. I go over each one separately and then leave it all on the table.

There are two women seated at a near-by table. One is whispering to the other. I am recognised.

“That’s ‘im; I tell you ’tis.”

“Ah, get out! And wot would ‘e be a-doin’ ‘ere?”

I pretend not to hear, not to notice. But it is too ominous. Suddenly a white funk comes over me and I rush out and into the taxi again. It’s closing time for a part of the afternoon. Something different. I am surprised. It makes me think it is Sunday. Then I learn that it is a new rule in effect since the war.

I am driving down Kennington Road again. Passing Kennington Cross.

‘Kennington Cross. It was here that I first discovered music, or where I first learned its rare beauty, a beauty that has gladdened and haunted me from that moment.’

It was here that I first discovered music, or where I first learned its rare beauty, a beauty that has gladdened and haunted me from that moment. It all happened one night while I was there, about midnight. I recall the whole thing so distinctly.

I was just a boy, and its beauty was like some sweet mystery. I did not understand. I only knew I loved it and I became reverent as the sounds carried themselves through my brain via my heart.

I suddenly became aware of a harmonica and a clarinet playing a weird, harmonious message. I learned later that it was “The Honeysuckle and the Bee.” It was played with such feeling that I became conscious for the first time of what melody really was. My first awakening to music.

I remembered how thrilled I was as the sweet sounds pealed into the night. I learned the words the next day. How I would love to hear it now, that same tune, that same way!

Conscious of it, yet defiant, I find myself singing the refrain softly to myself:

You are the honey, honeysuckle. I am the bee;

I’d like to sip the honey, dear, from those red lips. You see

I love you dearie, dearie, and I want you to love me—

You are my honey, honeysuckle. I am your bee.

Patricia Hammond and Ragtime Parlour, ‘The Honeysuckle and The Bee’: ‘I was just a boy, and its beauty was like some sweet mystery. I did not understand. I only knew I loved it and I became reverent as the sounds carried themselves through my brain via my heart.’

I suddenly became aware of a harmonica and a clarinet playing a weird, harmonious message. I learned later that it was “The Honeysuckle and the Bee.” It was played with such feeling that I became conscious for the first time of what melody really was. My first awakening to music.

Kennington Cross, where music first entered my soul. Trivial, perhaps, but it was the first time.

There are a few stragglers left as I pass on my way along Manchester Bridge at the Prince Road. They are still watching me. I feel that Kennington Road is alive to the fact that I am in it. I am hoping that they are feeling that I have come back, not that I am a stranger in the public eye.

I am on my way back. Crossing Westminster Bridge. I enter a new land. I go back to the Haymarket, back to the Ritz to dress for dinner.

My favourite autograph.