Director & Cinematographer: Jon Hall

Producer: Ed Janis

Writers: Joan Gardner (screenplay and story); Don Marquis (additional dialogue); Robert Silliphant (additional dialogue)

Music: Frank Sinatra Jr.; Chuck Slagle (conductor/music arranger)

Film Editing: Radley Metzger (uncredited)

Special Effects: Robert Hansard

Cast

Jon Hall (Dr. Otto Lindsay)

Sue Casey (Vicky Lindsay)

Walker Edmiston (Mark)

Elaine DuPont (Jane)

Arnold Lessing (Richard Lindsay)

Read Morgan (Sheriff Michaels)

Carolyn Williamson (Sue)

Kal Roberts (Brad)

Clyde Adler (Deputy Scott)

Dale Davis (Tom)

Kingsley the Lion (Himself)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M04rjjAfbwI

‘All the Right Ingredients for a Monster Camp Classic’

The Beach Girls and The Monster gathers all the right ingredients of a mid-’60s monster camp classic. First off it’s an American International Pictures-TV production, joining other of the studio’s cheesy releases such as the Larry Buchanan remakes of AIP films including It Conquered the World (Zontar, The Thing from Venus) and Invasion of the Saucer Men (The Eye Creatures). Other AIP-TV classically bad offerings include Mars Needs Women with John Ashley of the Frankie and Annette Beach Party series, and Curse of the Swamp Creature. These are examples more of AIP’s original material and not of the mass of dubbed foreign films from Japan or Italy the company released to American TV. The Beach Girls and The Monster may not have much going for it, but its soundtrack is truly memorable, being almost totally high-caliber surf music performed by a band called The Hustlers, from Riverside, CA (known in surf circles for their songs “Kopout,” “Wailin’ Out” and “Inertia”)–not just sappy beach party music, this, but actual reverb-drenched surf music with a clear Duane Eddy influence. In fact, in their book Pop Surf Culture: Music, Design, Film and Fashion from the Bohemian Surf Boom, authors Brian Chidester and Dominic Priore hail the soundtrack as ranking “among the best…no fewer than 13 different sections of full-bore, deep-reverb tank surf instrumentals throb the soundtrack.” The music includes a couple of swingin’ songs co-written by Frank Sinatra Jr. (including “Dance Baby Dance,” heard over the opening credits accompanying the movin’ and groovin’ of the Watusi Dancing Girls from the Whiskey A Go Go). According to Wikipedia, the surfing footage used in a scene in which Richard runs a film for Mark was shot by the legendary ‘60s surf filmmaker Dale Davis. Other virtues include the appearance of an aging ex-leading man actor in the person of Jon Hall, with The Beach Girls being his swan song film in which he acts, directs and even serves as his own cinematographer. Plus there is a totally unbelievable monster right out of the Paul Blaisdale school of monster suit making. This is one unforgettable monster. The movie clocks in at a mere sixty six minutes in this theatrical release (a longer version for TV exists somewhere with almost ten extra minutes of footage) and since it subscribes to the B-movie method of “action costs but talk is cheap” filmmaking it can drag on in places, but you’d have to be a Grinch, or a snob, to pooh-pooh it. If you’re looking for Citizen Kane, cue up Citizen Kane; this isn’t even the Citizen Kane of cheapo surfing-monster-beach girls films. How cheap? Apparently the interior shots of the Lindsay home were shot at the West Los Angeles (Brentwood) residence of Henry and Shirley Rose, friends of producer Edward Janis. Shirley Rose also served as the film’s art director. The office scene was shot at the business office of Henry Rose.

Following the groovy opening credits exploiting the Watusi Girls’ gyrations on the beach and actually showing the monster before the film begins, some supposed teenage guys, who look much older, come in from a surfing run. One of the beach girls, Bunny, plays a practical joke on her boyfriend and then runs off giggling down the beach with her beau in tow. In a bit of a randy scene for the time Bunny and beau roll around in the surf until he gets fed up and returns to the group and its reel-to-reel tape player blaring wild surf music. Adhering to its own internal logic, the film then has Bunny wandering into a cave, where she is soon set upon by a seaweed covered monster. The cops arrive and manage to (1) make plaster casts of the footprints, which they feel they need to take to local oceanographer Dr. Otto Lindsay (Jon Hall) and (2) deliver the most movie’s most priceless line of dialogue, to wit: “Well, Sheriff, it’s not the claw print of any fish in this area.” Dr. Lindsay’s immediate impression is that the prints are from the South American fantigua fish (don’t look it up; there is no such thing). However, this particular fish, which can live outside water and walk on land, would seem to be a mutated variety and must weigh over a hundred pounds.

The opening credits of The Beach Girls and The Monster features Frank Sinatra, Jr.’s surf classic, ‘Dance Baby Dance’

Inexplicably the film now shifts from a mutant monster murder mystery to a family soap opera drama. Seems Otto’s boy Richard (Arnold Lessing) has decided his life’s ambition is to be a cool surfer dude instead of following in his dad’s footsteps and becoming a dedicated scientist. The kid looks like he is about 27, but this is a niggling detail. Apparently Rick woke up to life after a car accident involving his father and a family friend named Mark (played by famous voiceover and character actor Walker Edmiston, who, in addition to appearing on Gunsmoke, Star Trek, Mission: Impossible and other top drawer TV fare, was also the voice of Erne the Keebler Elf in commercials for the Keebler Company; in the ‘50s and ‘60s he also had his own Walker Edmiston Show in Los Angeles, a children’s program featuring puppets of his own making, including Kingsley the Lion, who makes an appearance in The Beach Girls and The Monster). The injuries Mark suffered in the car accident have left him a bitter cripple who now lives upstairs in the Lindsay’s luxurious house making weird, topless mermaid sculptures of Rick’s beach girl friends. Mark and Rick decide it would be nice to give his most recent semi-nude sculpture of Bunny to her family, as a kind gesture. Mark also is crafting a disturbing looking bust of Otto’s “Mrs. Robinson” trophy wife Vicky (played to a T by Sue Casey), who rebuffs his romantic advances, telling him she would never consider making love to a cripple. She exits laughing, heading to the swanky bar in the living room where she proceeds to hit on Rick, who, far from being seduced, looks like he’s going to deck her.

Most of the film centers on all of this domestic turmoil with the monster and the twisting beach girls in a secondary role, even though they are the title characters. Of course there are murders, most of which usually involve the monster choking its victims and then scratching their faces. Everybody dies off easily enough, leading to the conclusion that having your face superficially clawed by this thing is enough to kill you instantly.

This movie and his uncredited work on Navy and the Night Monsters were Jon Hall’s only directorial jobs. Six-feet-one, handsome and athletic, he was quite the striking leading man in his early films (such as Arabian Nights and The Hurricane) but he didn’t age into older roles. The son of actor Felix Locher and a Tahitian princess, Hall was married three times, once to the popular singer Frances Langford, a Disney favorite. Apparently he was indifferent to his declining fortunes as an actor, telling one interviewer, “I never liked acting. I don’t like to be told what to do and what to say and how to say it. I’m grateful to it as it provided me with the money to do other things such as I’m into now, but as a profession, it’s a bore.” Sue Casey, Hall’s female lead, appeared in far better movies than this, including Show Boat, Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Camelot, the Academy Award-nominated An American in Paris and American Beauty (also an Oscar nominee) and in 1963 was cast as Mrs. Calvada on The Dick Van Dyke Show. Between 1945 and 2002 she appeared in more than 75 productions. She does a good job here as the unlikable gold-digger. The rest of the cast returned to the obscurity from whence they emerged, including the vivacious Watusi Dancing Girls.

By no stretch is this a good movie but it is eminently watchable if only for its campy, sometimes outright bad dialogue and that phony looking monster. The Watsui Girls are always pleasant eye-candy and, as noted earlier, the music stands out for its surf authenticity. As for Frank Sinatra Jr.’s presence, his tunes are fine—and not what you might expect from Jr. at all—but it seems obvious he was hired for the value of his name in the credits. In the end, ask yourself: Do I like beach movies? Do I like goofy monsters in laughable garb? Do I like bikini-clad girls twisting on the beach? If you answer yes to any of these questions, The Beach Girls and The Monster is must-see Deep Roots Theater.

Sources: The Uranium Cafe, June 23, 2012; Internet Archive; Wikipedia.

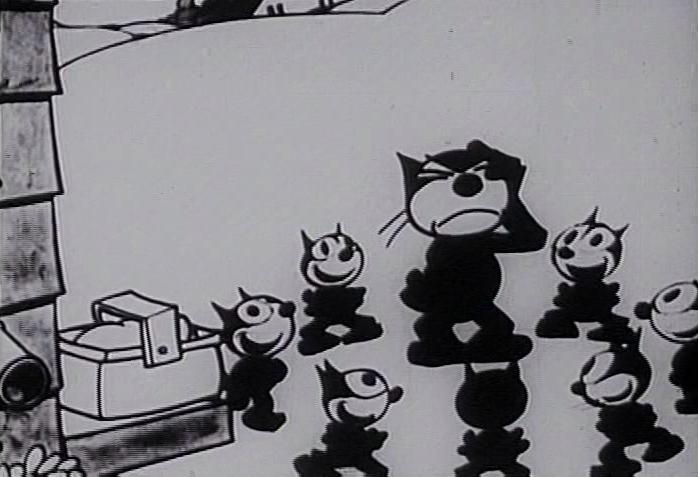

Selected Short Subject: Felix the Cat in ‘April Maze’ (1930)

Director-Writer: Pat Sullivan

Producer: Jacques Kopfstein

Starring: Felix the Cat, Inky, Winky

Produced and Distributed by Copley Studios

Felix brings his nephews Inky and Winky to the park for a picnic. However, they always seem to be delayed. While they say their grace, a rabbit gets a snake to steal their meal. When they try to get it back, it rains so they needed to go back home. Inky and Winky are upset and Felix does his best to carry them out on the picnic. Fortunately, the rain stops and the three continue to the picnic. It rains again for a short while, but then it gets better. They say their grace again before eating, and someone else steals their meal. Felix runs after the culprit however, he can’t catch him. At the end of the story, a stork comes with a picnic basket. Hoping the stork has found his meal, Felix opens the basket with joy, but he finds out it is just more kittens.

Inky and Winky make their most famous theatrical appearance in this short, which is occasionally mistaken for their only appearance. They actually debuted in Felix the Cat Weathers the Weather (1926), returning in several more 1920s shorts before April Maze. Sometimes three kittens were used, in which case the third was called Dinky. In Eskimotive (1928), Inky appeared solo. In the 1950s, Inky and Dinky appeared with Felix in their own comic books. The most common pairing of Inky and Winky began several years later. Although Felix’s nephews do not appear in the early-1960s and mid-1990s TV series, they have a considerable role in the online comics, making them among the principal characters in the Felix media.