Julia Trigg Crawford, landowner from Direct, Texas. Through Eminent Domain Trans Canada built part of the southern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline through her land against her wishes. Photo copyright Garth Lenz of the International League of Conservation Photographers, www.ilcp.com

From the Oglala Lakota Sioux on the Pine Ridge Reservation to the Rosebud Sioux and others, American Indians are standing firm against the Keystone XL pipeline, which would run through or skirt their territory if approved. Now, what started as a purely Native American protest against the pipeline has broadened to include ranchers from the 40-year-old Cowboy Indian Alliance, a coalition of tribal members, ranchers and landowners that has come together again and again over the past four decades to fight industrial incursions onto their land. This time, the fight is over the Keystone XL pipeline.

“The Cowboy Indian Alliance isn’t an anomaly,” reports National Georgraphic News Watch. “Across the continent, the fight to stop tar sands–and in particular the fight over Keystone XL–has catalyzed the creation of unlikely coalitions. And increasingly, it’s the ‘frontline’ leaders from the most at-risk communities who are taking the lead.”

The Lakota Sioux have been pushing back against TransCanada, the conglomerate that wants to run the 1,700-mile-long pipeline from the oil sands of Alberta to the Gulf Coast of Mexico, for years. The Rosebud Sioux have passed a unanimous resolution against the project. And a group of American Indian tribal leaders opposing the pipeline have vowed to take a “last stand” and are working together, training opponents to put up passive resistance if it comes to that.

“We see what the tar sand oil mining is causing in Canada, we see what the oil drilling in the Dakotas is doing—as they gouge her [Mother Nature] and rape her and hurt her, we know it’s all the same ecosystem that we all need to live in,” Lakota activist and Pine Ridge resident Debra White Plume told Inter Press Service News Agency (“An Environment-Wrecking Pipeline Hangs in Limbo”). “For us it’s a spiritual stand—-it’s our relative, it hurts us.”

‘For the past century, Lakota spiritual elders have had visions about ‘A black snake from the North’: Moccasins On the Ground leaders explain what draws them to protect the sacred water and address the question, Can a tipi stop a pipeline?

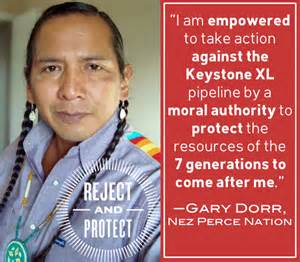

Keystone XL will cross through land considered sacred by various American Indian tribes as part of their traditional territory. Dallas Goldtooth, one of the organizers of April’s Reject and Protect gathering in Washington, D.C., and a member of the Lower Sioux Dakota Nation, says that “no matter the reservation boundaries, we still have a right to protect the land within the boundaries of that treaty”–the Fort Laramie Treaty–“which goes from the far eastern side of South Dakota past the Black Hills.” Contaminated land and water, Goldtooth says, would further endanger an impoverished part of the country that already has a history of being targeted for industrial projects.

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe approved a resolution on February 25 to reject outright a document that the federal government wants the tribe’s leaders to sign saying that they have been adequately consulted according to the law.

“This Programmatic Agreement for the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline project has not met the standards of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, because the Rosebud Sioux Tribe has not been consulted,” said Council Representative Russell Eagle Bear in a statement from the tribe. “Additionally, the Cultural Surveys that have been conducted already are inadequate and did not cover adequate on-the-ground coverage to verify known culturally sensitive sites and areas.”

‘We love the earth; we don’t want to see this happen’: Neil Young addresses the Reject & Protect Rally in Washington, D.C., April 26, 2014

‘’Why don’t the First Nations take the money? They need it.’ We don’t need it more than the land, and that’s why we’re here.’: Reject and Protect Prayer Ceremony and Round Dance with Chief Rueben George, April 25, 2014

Keystone XL would wend its way through the Great Sioux Nation, including the lands of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, making them the appropriate tribe to be consulted on land within Tripp, Gregory, Lyman, Todd, and Mellette Counties in South Dakota, the statement said.

“This is a flawed document and it will not be accepted,” Rosebud Sioux Tribal Council President Cyril Scott said of the federal agreement they are being asked to sign. “It is our job as the Tribal Council to take action to protect the health and welfare of our people, and this resolution puts the federal government on notice.”

It is not the first time the government has been accused of fabricating consultation. The first draft of the environmental assessment report, released a year ago, met with resistance from tribes over what they said were inaccuracies, shoddy research and incomplete consultation, among other objections.

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) also came out against the conclusions in the draft environmental assessment.

The U.S. Department of State is currently evaluating the final version of the environmental assessment report and accepting input from several federal agencies during a 90-day public comment period that began on January 31, when the report was issued, according to U.S. News & World Report. The State Department is also studying the consultants on the report as more and more revelations about their ties to TransCanada come to light.

Oklahomans from across the state, and indigenous and environmental activists came together and walked onto an easement where pipe for the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline was being laid through Sac & Fox land. In solidarity with the international Idle No More movement, the Unis’tot’en Camp, impacted communities throughout the pipeline route and an Oklahoma branch of Tar Sands Blockade have come together to take nonviolent action against the dangerous pipeline and demand that tribal sovereignty, native burial lands and property rights be respected by TransCanada. The action took place in Stroud, OK, where the group walked onto a TransCanada easement and marched along segments of buried and unburied pipe, participating in round-dances along the way.

Julia Trigg Crawford, a landowner from Direct, Texas, has been fighting Keystone XL since 2008. Keystone XL already runs through Crawford’s fields, and the oil began flowing in January. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court of Texas rejected her case against the pipeline company TransCanada, who claimed right of way to her land through eminent domain. But Crawford hasn’t given up.

Crawford fears that the tar sands pipeline will one day spill, destroying her land and polluting her water. This isn’t an unthinkable supposition: According to an NRDC report, tar sands diluted bitumen is 3.6 times more likely to spill than regular oil. If that weren’t enough of a red flag, the proposed path crosses the Ogallala aquifer, which provides drinking water to eight states—threatening not just the drinking water for millions of people, but the stability of the region’s agricultural economy.

The pipe buried in her land is seafoam green, Crawford says, “but it should be blood red.”

The Native group Moccasins on the Ground has been conducting training sessions and recently hosted a conference in Rapid City, Help Save Mother Earth from the Keystone Pipeline, to teach civil disobedience tactics.

“As the process of public comment, hearings, and other aspects of an international application continue, each door is closing to protecting sacred water and our Human Right to Water,” said Debra White Plume, a Lakota activist who lives on the Pine Ridge Reservation and has been very vocal in opposing the pipeline, in a statement from Moccasins on the Ground. “Soon the only door left open will be the door to direct action.”

Part of Dallas Goldtooth’s role at Reject and Protect was to be a bridge between the indigenous and nonindigenous alliance members–to facilitate communication between two groups who still have significant differences. His role is emblematic of this generation of young native activists, which, he says, is at an “intersection of sorts between old school and new school.” Younger people like Goldtooth have inherited traditions from their forerunners, but–thanks to social media–are part of networks that are connecting both indigenous and nonindigenous people in truly unprecedented ways.

These indigenous leaders, ranchers and landowners share a healthy mistrust of both big government and industry, but it is ultimately the land itself that unites them; their cultures, identities and histories are all rooted in these hills, and this soil.

“It’s no surprise to me that Mother Earth is what’s bringing us together,” says Goldtooth–literally, on “common ground.”

RELATED: State Department Investigates Its Own Keystone XL Environmental Consultant

Sources: Indian Country Today Media Network; Reject and Protect.org; National Geographic News Watch