Of the untold number of poems and scholarly treatises inspired by the story of Jesus’ resurrection, none have engendered as much speculation, interpretation and consideration as to its greater meaning than John Updike’s ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter.’ In marking Easter and the Pentecost in Deep Roots, we continue our tradition, dating back to the April 2011 issue of TheBluegrassSpecial.com, of offering the Updike poem; the story of its discovery in 1960 when the young poet entered it in a Massachusetts church’s Religious Arts Festival and won a $100 prize for ‘Best of Show’; and, in ‘Seven Voices on Seven Stanzas,’ seven new perspectives each year, from lay people and clergy alike, reflecting on either their personal experience with Updike’s poem or their perspective on its theological import in today’s world. In these carefully selected ‘voices’ we look not for blind praise of Updike’s stance but rather insight based on sound theology as to the poem’s application in the everyday lives of people of faith—or even how those lacking faith can still take something of value from the poem.

Seven Stanzas for Easter

By John Updike

(from Telephone Poles and Other Poems, 1963)

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cell’s dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers,

Each soft Spring recurrent;

It was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled

eyes of the eleven apostles;

It was as His flesh; ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes

The same valved heart

That-pierced-died, withered, paused, and then

Regathered out of enduring Might

New strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence;

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the

Faded credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-maché,

Not a stone in a story,

But the vast rock of materiality that in the slow

grinding of time will eclipse for each of us

The wide light of day.

And if we have an angel at the tomb,

Make it a real angel,

Weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair,

Opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen

Spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

For our own convenience, our own sense of beauty,

Lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are

Embarrassed by the miracle,

And crushed by remonstrance.

The Story Behind ‘Seven Stanzas’

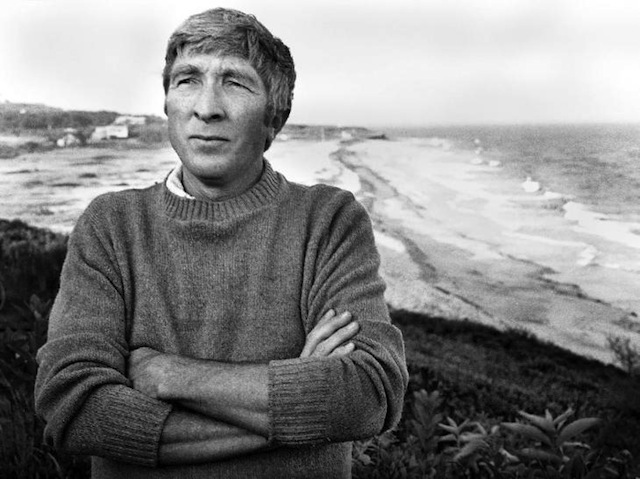

Norman D. Kretzmann remembers John Updike as a young Harvard graduate who sought out Clifton Lutheran Church in Marblehead, Mass., because it “nurtured the roots of faith he had grown up with in Pennsylvania.”

Kretzmann, pastor of Marblehead at the time, proudly recalls that Updike was among the 96 adults who entered the congregation’s Religious Arts Festival in 1960–and that his poem, “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” won $100 for “Best of Show.”

“People in the parishes I served became quite accustomed to my quoting his poem in my Easter sermons at least every few years,” says Kretzmann, who lives in a Minneapolis retirement center and regularly contributes to the Metro Lutheran newspaper.

Kretzmann closely follows Updike’s work, which includes more than 50 novels and books of poems. In a Metro Lutheran review of John Updike and Religion (Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000) he wrote: “I was John Updike’s pastor during the time which the writer later described as his ‘angst-besmogged period.’ Who was the rabbi and who was the disciple of our years together is hard to say.”

The pastor still has Updike’s 41-year-old typed copy of “Seven Stanzas”–“marked up with all sorts of irrelevant notes by me, instructions to me for homiletical purposes or for various secretaries,” he said. And Kretzmann has one more fond memory from the festival: Updike gave the $100 prize back to the congregation.

–by Kathleen Kastilahn, posted at The Lutheran.org

SEVEN VOICES ON ‘SEVEN STANZAS’

I

Seven Stanzas At Easter: A Poem for Sunday

by David J. Lose

‘Anastasis’ is the Greek word for ‘resurrection.’ Depictions of anastasis don’t reference the biblical story of Christ’s resurrection, but are inspired by the Gospel of Nicodemus (also called ‘Acts of Pilate’), an apocryphal text. These scenes show a triumphant, victorious Christ who has broken the Gates of Hell in order to rescue his Hebrew forbearers. Probably the best known anastasis painting is this one. Here, Christ is shown rescuing Adam and Eve from their tombs. Other patriarchs, prophets, and kings wait on the sidelines–perhaps waiting their turn to be rescued by Christ.

I’ve always had something of an ambivalent attitude towards John Updike. I’ve known his work for ages–he grew up in Shillington, PA, just a stone’s throw or so from where I grew up. He was raised a Lutheran, an upbringing that he seemed to struggle with as well as be marked by. I’ve loved his short stories as much as anything I’ve ever read, but sometimes been less than taken by even his celebrated novels. I don’t know why – perhaps they were too “earthy” for this kid. But it’s precisely the “earthiness” of “Seven Stanzas at Easter” that I love about this poem. If you’re going to believe, Updike seems to say, then believe. Stop trying to soften the edges of Christian faith or make it more acceptable. And I think he’s right – “modernize” the resurrection – by making it a metaphor or parable or the disciples’ dream or psychological experience – and you lose something essential not just of the story but of the very promise of God to remake everything as real and tangible and alive as God made it in the first place.

The post image, from the familiar Greek icon Anastasis (Resurrection) is one of my favorite images for Easter because it shows the usually placid Christ actually straining to pull Adam and Eve from the clutches of death and hell. I think it compliments the sensibilities Updike expresses in his poem.

Blessed Easter, one and all!

Posted at …In the Meantime, April 8, 2012

II

Let Us Not Mock God with Metaphor: John Updike on the Resurrection

by William Smith

The Pulitzer Prize winning writer John Updike is not one who readily comes to mind as someone who held the historic Christian faith. But he did in the sense that confessed the Apostles’ Creed taking the words to mean what they say. He once said, “I call myself a Christian by defining ‘a Christian’ as ‘a person willing to profess the Apostles’ Creed.’”

I have read a little but not much Updike. What I remember from what I have read is the feeling that he “got it” when it came to understanding the human condition and predicament.

He was brought up as a Lutheran and died as an Episcopalian. I am not here trying to judge whether or not the man was “a true Christian ” as some would put it. That is not our judgment to make. Our Confession calls “true Christians” the elect who make up the invisible church, which is known to God alone.

Nor is it our role as individuals to judge his profession of faith. That is a judgment for the visible church to make. Updike was a Christian in the sense that he was a part of the visible church and professed the Christian faith as stated in the Apostles’ Creed.

His poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter” demonstrates how literally he took the Creed by asserting that the resurrection is either a real, bodily resurrection, or there is no Christian faith or Christian Church.

Updike’s affirmation of the bodily resurrection of our Lord in the poem is so clear that the writer of the blog, The Questioning Christian, was very upset to hear part of it quoted at the Sunrise Service he attended (“John Updike Blows It About the Resurrection”):

“At the otherwise-wonderful Great Vigil of Easter this morning (a.k.a. the sunrise service), our rector quoted from John Updike’s Seven Stanzas at Easter in his sermon:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle

the Church will fall.

“I’ve tried and failed to read these lines, and the rest of the work, as merely a literary device. They’re not. Updike is clearly drawing a line in the sand about what he thinks actually happened on Easter Sunday.

“I can’t understand how Updike can be so certain. We simply don’t know what happened on that Sunday so long ago …”

Ah, but Updike was certain–certain at least that without the bodily resurrection of Christ there is no Christian faith. As Paul said, “And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain, and your faith is in vain…your faith is futile and you are still in your sins” (1 Corinthians 15: 14, 17).

“But in fact, Christ has been raised from the dead…” (1 Corinthians 15: 20).

William Smith is a Teaching Elder in the Presbyterian Church of America. He is a writer and contributor to a number of Reformed journals and resides in Jackson, MS. This article first appeared at his blog, The Christian Curmudgeon, and is used with his permission.

III

‘Seven Stanzas’: Some Thoughts

by HEEBZ

Here’s what I love about Updike’s poem —

1. It gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection.

2. It speaks our language.

When I say that it gives the appropriate importance to the resurrection, I mean that Updike sees this event as the central event in the Christian faith, with out, “the Church will fall.”

This has been my constant refrain against those who attempt to use science to assail Christianity. Most jump to Genesis 1 and 2 and attempt to refute the creation stories with evidence of a 14 billion year old universe. I heartily agree with them and say: “Yes, I too think the universe is that old. Let’s also talk about the 4.5 billion year old Earth!” If the story of Adam and Eve or either of the creation stories in the Hebrew Bible are shown to be ahistorical, the Church will not fail. These stories are interesting, but they aren’t the heart of the faith. The heart of Christianity is found in Christ and more specifically in his resurrection. Consider this: Jesus dies as the vast majority of his disciples have abandoned him. The resurrection is that event which brings them back together, galvanizes them, and reinvigorates them for the life of persecution that they will lead in the wake of the scandal.

For the Christian, the resurrection is the ballgame; it’s everything.

Second, I love that the poem speaks our language. It mixes in the language of quantum physics, biology, and medicine. Updike doesn’t ask us to shy away from the scientific implications of the resurrection; instead, he asks us to consider them part of the miracle. The resurrection is real, down to the amino acids involved and the existence of the angel in our dimension.

This is good stuff. Thank you, Mr. Updike. May you rest in peace!

Originally published at the HEEBZ blog.

HEEBZ is S.B. Hebert, a Teacher and Assistant Chaplain at St. Mark’s School in Southborough, Massachusetts. He has been married since 2002 and a father since 2011. His wife, Natalie, is a talented photographer. “HEEBZ* is just my personal thoughts as I work through life with my family, friends, and Jesus.” (*The title of the blog comes from the nickname that my students have given me: “Heebs.” Now you’re in the know…)

IV

‘Christians Believe Something Amazing Happened Today’

by Hap Mansfield

It’s Easter and Christians believe that something amazing happened today: a man rose from the dead. If we don’t believe that Jesus was a man, it’s no big trick to rise from the dead. One supposes that God can do anything if he/she is a God worth the worship so rising from the dead is pretty much just a parlor trick. The fact that Jesus was a flesh and blood man that rose from the dead is astounding. It’s supposed to be. Glossing over it does God a great disservice.

I would never presume to proselytize for Christianity. I am unqualified to do so since my personal beliefs are a vertiginous mix of Hindu-Buddhist-Christian-Pagan. But, Updike is saying something wildly important about Christianity and the church that often gets smoothed down and varnished. The resurrection of Jesus from the dead is what sets Christianity apart: their God is alive. Jesus lives.

Updike is forcing us to look at this resurrection as a real event and describes it as such. There is no blond Northern European in this tale. You wanna know what they looked like? They probably looked a great deal like the people we are fighting in the Middle East. Updike’s angel is clad in real linen spun on a loom, the principles of physics hold tight, Jesus has real flesh. The miracle is not merely a metaphor but a real event at a stinky tomb on hot day in the desert.

Detail from a mid-13th century psalter showing Mary Magdelen’s encounter with the risen Jesus. Photo courtesy British Library MS Royal 2B iii.

Whatever you or I feel about religion, think on this: the violence, distrust, iron rules, male-domination, rape and sexism of the so-called “Old Testament” is dead the day that Jesus rises from the dead. It’s gone and replaced by a new covenant. Jesus says that the two most important things one can do in life are to love God and to love one’s neighbor. Respect all people, care for them, and love God. Christianity is not an exclusive club–anyone can join.

And anybody who says any different has not read their Bible. Christians who dwell on the “Old Testament” are both bad Christians and bad Jews–they are cherry-picking the Bible to support vindictiveness, prejudice and war. By the by, there is a term circulating in the media that is an oxymoron: “Old Testament Christian.” It would be funny if it weren’t so blatantly ignorant. One must try to forgive these people for their silliness; they are obviously scared of love and peace for some reason.

So on this Easter day, it’s good to celebrate the life of the new church, the church Jesus hoped would be one of forgiveness, tolerance and love for all people. Doesn’t it strike you with awe and reverence that we are all evolved from the same initial life on earth? That we are all cut from the same cloth?

How many ways do we have to hear this story until we believe it?

From Hyacinths and Biscuits: Number 317, April 8, 2012

V

‘A Psychology of Awakening’

by Hedda Ben-Bassat

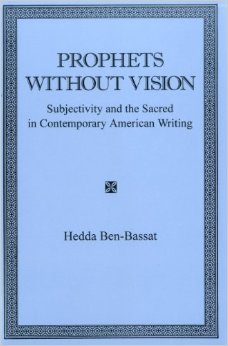

(The following is a brief excerpt from Hedda Ben-Bassat’s book Prophets Without Vision: Subjectivity and the Sacred in Contemporary American Writing [Associated University Presses, 2000] “about crises of ideology and identity in the fiction of five contemporary American writers—John Updike, Flannery O’Connor, Grace Paley, James Baldwin and Alice Walker. In the following passages Ms. Ben-Bassat compares and contrasts Updikes “intertextual allusions” to Swiss theologian Karl Barth’s Crisis Theology specifically in Updike’s “Seven Stanzas at Easter.”)

No wonder that Updike chose Barth as the challenging double to the Emersonian model of prophetic selfhood. Just to illustrate the intriguing intertextual relation between Updike’s dark Barthian double and his surface American unconcern, it is worth comparing the metaphor Updike uses to diminish the titan, with the very metaphor Barth uses in similar context. “We are in some deep way scared by how unthinkably small our place in the universe is,” Updike claims. “We’re almost creatures of gossamer, aren’t we?” (Conversations, 204). Barth, likewise, highlights man’s earthly existence in a “sick old world,” in which “the whole network of life is hung upon thread like gossamer” (The Word of God, 188).

Moving from imagery to ideology increases our appreciation of Updike’s apocalyptic moments. For Updike as for Barth, apocalypse does not correspond with the Second Coming of Christ at the end of time. Rather, it coincides with Christ’s ritual resurrection every Easter, and with the psychological moment of awakening, marking for the individual believer the moment of identification with Christ. This Barthian standpoint is expressed by Updike in his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter.” The poem translates, in Barthian fashion, the theology of resurrection into a psychology of awakening. The scandalous fact of Christ’s death and resurrection is seen as man’s passage or conversion from the old (oblivious) to the new (awakened) self:

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous,

for our own convenience…

lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour,

we are…

crushed by remonstrance

The two states of sleep and awakening are encouraged by two opposite prophetic figures in Updike, as in Barth. The theologian distinguishes in contemporary existence between two prophet figures. The false prophet, who is “easy-going, someone you can live with as you are,” serves the old and sinful man, who resists being awakened to judgment. The true prophet, by contrast, is “a man who most uncomfortably questions everything…about whom you are never sure, like a meteor of unknown whence and wither.” He guides the individual in the choice between the uncaring life of the old man, and the anxiety of the crisis leading to the new man in God: “You cannot demand that I should tell you about God and also accept things as they are. This is impossible. You must choose one of the two: one, not both. Decide!”

VI

Easter Wisdom: ‘Easter Is the Miracle We Need’

by Bob Beverley

Do you know the poem by John Updike called “Seven Stanzas at Easter”? In it Updike wrestles with the ideas put forth by various ministers and theologians that the resurrection of Christ may not have been a bodily resurrection, but merely a believed story that is only important because it symbolizes some general nice truths like “You can start over” and “Try freshening things up a bit” and “Don’t give up your hope.” In their sense Easter is sort of a Spring-like symbol, but not an actual occurrence.

As a psychotherapist, I’m all for hope and fresh starts and starting over. But if I were going to use Easter as a symbol, I would add a few dimensions that aren’t quite so delicate and soft. Now I certainly cherish soft and delicate things. Who does not delight in flowers, bunny rabbits, and children? But Easter as a symbol can be harder, louder, and more explosive because Easter represents much more powerful wisdom.

Ponder the Easter story and I think you’ll agree…….

Easter is massive interruption. It is a new world dawning from out of nowhere. Easter is the idea that you will be helped by a greatness that is far greater than you. Easter is mind-blowing alternative—a powerful onslaught to the way you thought things were going to be. Easter is “this way of being and living is dead and gone”—here is something else, the totally unexpected, the fresh beyond imagination new beginning.

In this sense, Easter is one huge stop sign and one unforeseen giant green light beckoning you to a whole new world.

Easter is an ax.

It is a cataclysm. It is an “Oh my God” phenomena.

Easter is the miracle we need.

Think about your problems. Don’t you need more Easter in you and outside you to demolish those problems? Don’t you need some unexpected reality to come along and move the stone of your deadness and wake you up to new life?

And is this not what happens so often when we do in fact finally and slowly change? Here we are chugging along with our problems and struggles and old habits and foggy ideas when along comes a movie, a line from a song, a sentence in a novel, a word from a friend, a shout from a therapist, a firm directive from a stranger—and suddenly we see the possibility that we no longer have to live this way and right now we can change and, right now, miracle of bigger miracles, we do change and, in a certain way, become unrecognizable.

William James was getting at this when he offered this advice on how to change our life:

1. Start immediately

2. Do it flamboyantly

3. No exceptions

My first therapist of long ago (the blessed Ralph Fogg from New Paltz, New York who retired and moved to North Carolina but who lives in my mind and heart forever) was getting at this when he used to tell me “Robert, progress is the enemy of getting well and you don’t need progress, you need a revolution.”

I offer the Updike poem not as part of a religious debate, rather as a symbolic warning that we be careful how we water down things down and make them manageable and cozy and tidy when in fact what we need is something that will not conform to our comfort—but instead with its realness bring us the revolution we need.

From Bob Beverley’s Find Wisdom Now. Bob is a psychotherapist in the mid-Hudson valley of New York State. He has written How to Be a Christian and Still Be Sane and The Secret Behind the Secret Law of Attraction (with Kevin Hogan, Dave Lakhani, and Blair Warren). Bob is available for motivational speaking, consultation, and psychotherapy. Bob is also the leader of a unique, life-changing experience called THE M GROUP.

Bob has written several ebooks including: How to be Wildly Successful Even If You Know You Are A Loser, Get Books! Get Wisdom!, The Power of Fear, and The Core. These books contain shortcuts to wisdom and success. Bob shares insights that will stretch anyone to a bigger, happier, more loving life. For more information click on the Books link to the left.

Bob is a native of New Brunswick, Canada. He graduated with a degree in philosophy and English Literature from Gordon College, Wenham, Mass. He spent a junior year abroad at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. He received a Masters of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary. Bob received a Certificate in Psychotherapy and Marriage and Family Therapy from the Blanton-Peale Graduate Institute in New York City in 1991.

VII

A Question of Faith

Resurrection with John and John: ‘Seven Stanzas at Easter’ by John Updike; John 20:24-28

By Rev. Andrew Taylor-Troutman

John Updike begins his poem, “Make no mistake: if He rose at all / it was as His body” and, with that short phrase, one of our greatest writers dives into perhaps the central debate of Christian theology. Since the Apostle Thomas, people have wondered, “What is the meaning of the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ?” We’ll come back to Thomas in a moment . . .

But for now, I note that Updike is familiar with some of our modern answers to the question of the resurrection. It is sometimes argued that the ancient beliefs of the Church need to be updated for this current generation; that we need to make our complicated doctrines more accessible. And so preachers search for a metaphor, an image, or sermon illustration to put the meaning of Easter in plain words. Perhaps you have heard sermons that compare Christ’s resurrection to the changing of seasons: what Updike refers to as “the flowers / each soft Spring recurrent.” Or, maybe the resurrection is rationalized as a purely spiritual experience, an enlightenment of the mind: again Updike – “His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled eyes of the eleven apostles.” However noble or virtuous the intent, we pastors get into trouble by trying to explain the unexplainable.

In a short story called “Pigeon Feathers,” Updike has a young teenage boy ask his pastor about the meaning of the resurrection. The pastor responds that, just as Abraham Lincoln’s legacy as the greatest president and emancipator of the slaves continues after his death, so too Jesus’ reputation follows him as well. This pastor claims that it is our goodness that lives on after we die. At first blush, you might agree with this basic claim; but is that the resurrection?

In our poem, Updike forcibly rejects this idea and the notion that we can somehow rationalize the mystery: “Let us not mock God with metaphor, analogy, sidestepping transcendence / making of the event a parable.” If we make the resurrection a parable, a metaphor, or anything comparable to our everyday world, we commit idolatry by putting God into a box of our own making. As Updike writes, we make God “for our own convenience / our own sense of beauty.” This God of our own making is not worthy of worship; it is like a paper-mache rock. There must be something more . . .

In the Gospel of John, Thomas states the conditions necessary for him to believe; he must see the mark of the nails in Jesus’ hands and touch his side where the spear pierced him. Implicit in this understanding is that Jesus had a bodily resurrection. He was not a mere spirit or soul. And neither was his resurrection a matter of the cycle of life, such as the changing of winter into spring. This event breaks the cycle of life! More specifically, it represents the in-breaking of God into the world in a completely new way. Now that is a God worthy of worship!

I know that he’s known as the “doubter,” but let’s give Thomas some credit. He was not satisfied with easy answers; in fact, he didn’t ask for an explanation at all. He didn’t crave knowledge; he wanted a supernatural experience. And notice the result: Thomas gives as heartfelt a confession of faith as found anywhere in John’s Gospel, “My Lord and my God!”

Updike once claimed that the trouble with the modern church is that we have accepted an “easy humanism” instead of an “otherworldly stand.” We are too quick to explain away the mystery, too eager to present the Easter faith as a rationale explanation; and we do this both for our convenience and at the peril of the Church. Instead of inviting people to experience the transcendent power of the Almighty, we over-simplify and dumb-down the sacred mystery. No wonder, then, that more and more people are leaving the church, instead of exclaiming, “My Lord and my God!”

For today, I want to leave you with the image in John’s Gospel concerning locked doors. The disciples were hidden inside because of their fear; too often, we hide behind barriers of our own making that we call “explanations” or “logic” or “reason.” I want to suggest that, underneath these feelings, there is a kind of fear: the fear of the unknown, the fear of letting go of our need for answers and trusting God. There is a fear to the idea that we are called to walk by faith, not by sight. It is like moving forward by walking backwards; we don’t know what is ahead . . .

Yet Updike tells us, plainly and clearly, “Let us walk through the door.” If you have doubts, like Thomas, fine: God will come to you. Walk through the door! The point is not to explain the bodily resurrection or understand the empty tomb; our goal should not be to comprehend the mysteries of God. We don’t know how Jesus walked through the locked doors! But that should not prevent us from crying out, “My Lord and my God!” Walk through the door!

We’ll conclude our service with a hymn that speaks to this idea very well. John Bell, a member of a Presbyterian monastic community in Scotland, has written this text called “The Summons.” As you sing this hymn, I want you to notice that the first four verses all raise questions, as opposed to giving answers. The question is not do you understand, but are you willing to follow? That is a question of walking by faith, not sight. Let us stand and worship the One who is unimaginably great.

Rev. Andrew Taylor-Troutman

New Dublin Presbyterian Church

Dublin Ministerial Association

Homily from the community Holy Week service in Dublin

March 28th, 2013

About Andrew Taylor-Troutman

I am a pastor and a preacher, a writer, a husband and a father. My professional and personal lives are deeply involved with story-telling: stories that are silly and poignant or profound and commonplace. Stories that are tear-jerkers and belly-shakers. Stories about my son, Sam, and the congregation I serve, New Dublin Presbyterian Church. Each in its own way, these personal narratives shed light on the great story that God is writing with humankind and all of creation.

The Resurrection of Christ (1700) by the 18th century French painter Noël Coypel depicts Jesus’ glorious, but brief, return to life on earth; his victory over death in fulfillment of the Scriptures. Though Coypel seems to draw heavily on Matthew’s Gospel account, he nevertheless takes creative liberties to present a vision of the Resurrection entirely unique to him. In this interpretation, Jesus makes a much grander entrance, emerging from dark clouds in a burst of light, eyes lifted towards the heavens. He holds aloft a triumphant white banner with a red cross in its center, looking every bit the part of ‘Christus Victor,’ the savior who, through his earthly death, has freed his people from the bonds of sin and Satan and has instead given them the gift of eternal life (Galli). Coypel’s Jesus is a perfect divine liberator. –excerpt from ‘Darkness and Light in Noël Coypel’s The Resurrection of Jesus Christ essay posted at sniteartmuseum.nd.edu.