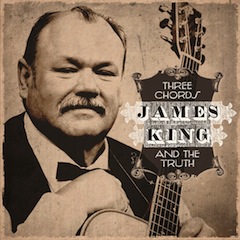

THREE CHORDS AND THE TRUTH

James King

Rounder (2013)

In 1988 one of country music’s greatest male singers, Vern Gosdin, cut an unbelievably powerful treatment of “Chiseled in Stone.” That it peaked at #6 on the country chart is also unbelievable, for a different reason, but the single remains one of Gosdin’s and country music’s late 20th century monuments. I’m sure James King wasn’t trying to make anyone forget Vern’s version when he cut “Chiseled in Stone” on his new album, Three Chords and the Truth (the title taken from the late, great Harlan Howard’s definition of a great country song), but King’s treatment is so raw in its abject regret over the fallout from words spoken in anger to his beloved that he seems to become the song, not merely its singer. Great vocalists will lose themselves in and to a lyric, but on “Chiseled in Stone,” and pretty much all of Three Chords and The Truth, he does it again, and again, and again. Those critics hailing this as King’s finest album aren’t just bumping their gums—it’s a classic of interpretive singing, a real peak moment for one of the great roots singers of our time.

James King, a live version of Vern Gosdin’s ‘Chiseled in Stone.’ The studio version is included on Three Chords and The Truth. Video posted at YouTube by dschram1. Filmed at Tir Na Nog, Raleigh, NC, IBMA Wide Open Bluegrass, September 25, 2013.

King has some imposing fellows aiding his efforts here, and it’s fair to say they rose to the challenge his singing posed. His harmony partners, Don Rigsby and Dudley Connell, understand every nuance of their leader’s phrasing and exactly how to shade their parts to augment the emotional moment. The band is a roots Murderer’s Row, with Jimmy Mattingly on fiddle, Josh Williams on guitar, the Boxcars (see review elsewhere in this issue) Ron Stewart on banjo, Jesse Brock on mandolin and Jason Moore on bass—these are gents that can play with fire and fury or with a keen sense of the depth of the despairing spectacle their atmospherics underscore. If they had done nothing more than strip “He Stopped Loving Her Today” down to a few succinct, lonely instrumental flourishes behind King’s Homeric wails and tear-stained cries this album would be one for the ages. The delicacy of Brock’s mandolin and the soft weeping of Mattingly’s fiddle make the exquisite timing of Rigsby’s and Connell’s final entrance almost too much to bear in an arrangement that carries a wallop without having all that much going on around King’s vocal, the effect being to heighten the impact and even the wonder the singer feels for a man who carried his flame for a lost love all the way to his grave.

As you can tell so far, King didn’t shy away from some towering songs in his choices for Three Chords and The Truth. He also does a terrific job of dealing the essential heartbreak of Don Gibson’s “Blue Blue Day,” with Stewart’s banjo driving the whole enterprise at a brisk pace ahead of Brock’s frisky mandolin solo, in a bluegrass-based arrangement that brings out a whole different feel than Gibson delivered on his classic single. The most drastic reworking here is Billy Joe Shaver’s “Old Five and Dimers.” Where Waylon took it at a slow, morose pace, a song rife with acceptance of limited horizons, King and company pick up the pace, again with Stewart’s banjo leading the way, to where the singer sounds undaunted by the prospect of not quite ever getting over the hump in life, even emboldened by the fact of having a woman promising to hang in “when everything ran out on me.” Williams and Stewart provide a lively one-two punch with back-to-back guitar and banjo solos, and an upbeat King goes out at album’s end taking something positive from a lyric that rarely gives off such a vibe.

A rousing version of Cliff Carlisle’s ‘Devil’s Train,’ recorded by Hank Williams and covered by James King on Three Chords and The Truth. Video posted at YouTube by dschram1. Filmed at Tir Na Nog, Raleigh, NC, IBMA Wide Open Bluegrass, September 25, 2013.

Other, lesser-known songs from country’s and bluegrass’s back pages form the bulk of the album, though. Gentleman Jim Reeves did a fine job in 1955 with “Highway to Nowhere,” a heartbreaker in the pop-country mode he mined so well; the heartbreak is even more pronounced in King’s version, but the honky tonk flourishes of Reeves’s recording have been supplanted by the steady thump of a midtempo bluegrass arrangement with a bright lead by King who moves into a lower range during the choruses, gives room for tasty solos by Brock and Mattingly and works up an affecting vocal blend when harmonizing with Rigsby and Connell. Of more recent vintage is a potent story song indebted to Red Sovine’s “Phantom 309,” “Riding with Private Malone,” a 2001 hit for neo-honky tonker David Ball. In a moderately paced bluegrass arrangement punctuated by Mattingly’s reflective fiddling, King tells of buying a ’66 Corvette that was once owned by a young soldier killed in Vietnam who “fought for his country but never made it home” but whose presence the singer feels whenever he’s driving the car. You can probably guess what happens when the car’s new owner totals the ‘vette in “a fiery crash” and lives to tell the tale, thanks to a ghostly helping hand pulling him to safety. No melodrama, though—King handles the scene with aplomb, right up to the close when he utters a soft, “Thank God I was riding with Private Malone.” A Cliff Carlisle song once recorded by Hank Williams, “The Devil’s Train,” kicks off the album in a full-on sprint of a bluegrass gospel sort with King hitting the lyrics hard, coming as close to shouting as he does anywhere on the album, in advising his listeners to get right with God before Satan’s temptations lure them the irretrievably the wrong way. Listening to Brock’s breathtaking mandolin solos, fleet and precise, you might wonder if he hasn’t made a pact with that fallen angel in return for playing with such furious fluidity.

AUDIO CLIP: ‘Riding with Private Malone,’ James King, from Three Chords and The Truth

Thus some, about half, of the wonders of Three Chords and The Truth. There’s more where those came from, and whether it’s Harlan Howard’s biting toe-tapper “Sunday Morning Christian” (a Howard jab at religious hypocrisy that he recorded himself) or the more deliberately paced stunner, “Jason’s Farm,” a Cal Smith hit from 1975 that tells of a farmer who makes something of a barren 300 acres, weds a supportive bride and reaps all the benefits of his bountiful crops and happy marriage. But his wife dies in childbirth and Jason turns his back on the land, on his child and on his God until “nothing grows no more on Jason’s farm.” There’s a lot of meat on the bones of this album. James King is so superior a vocalist he could tackle a half-baked lyric and make you feel something you never guessed was there (and that other, lesser singers couldn’t pry loose), but he’s offering a bunch of teachable moments here. Put that moral backbone together with transcendent musicality and you have something else again, something on the order of a bonafide classic.