The early recordings of Peru’s Juaneco y su Combo are featured on The Birth of Jungle Cumbia from The Vital Record

In the early 1970s, a small and largely unknown city called Pucallpa, nestled in the heart of the Amazon jungle on the far side of the Peruvian Andes, was the birthplace of a genre of music that would become a regional phenomenon and a white whale for Latin music collectors many years later. A mid-century oil boom brought workers to the region to toil daily in the oppressive equatorial heat. Hard living often begets inspired music, the kind that can only be created by people seeking an escape–physical, metaphysical, both–from and needing to reflect on and chronicle the drudgery of their days while at the same time celebrating their common bond in life. Out of these conditions came Juaneco y su Combo in the late 1960s. At first they were a standard, six-man dance band playing waltzes and polkas and dressing in conservative contemporary styles. But as the band expanded and made other key changes in its approach, its original music became an expression of the conscience and the culture of the Amazonian jungle people. Out of a kitchen sink of influences that included American surf and psychedelic music along with traditional Latin stylings came a new sound–jungle cumbia, it was dubbed, a genre that now holds near-mythical status for fans of South American music. Named after its leader, the band called first called itself Juaneco y so Conjunto, then evolved to the name by which it became famous locally–and now legendary in world music–Juaneco y su Combo. The group’s amazing achievements are muted only by the horrific tragedy that cut short their golden era–a 1976 plane crash in which more than half the band died. Juaneco y su Combo’s first records were released by the Lima-based IMSA label in 1970 and 1972, and it is these early recordings, never before released internationally and out of print for the past 40 years, that comprise the essential, breathtaking anthology The Birth of Jungle Cumbia, as issued the U.S.-based label The Vital Record (not to be confused with Vital Records in Olympia, Washington). Recorded between 1970 and 1972, these are the obscure first sides of the jungle cumbia pioneers before they were signed by a big label and subsequently produced in a more polished and pop-y style to appeal to an audience outside the Amazon region. As the first instance of a jungle band recording its own compositions, this album captures a unique moment in Latin music history. The invaluable CD comes with a lavishly designed, informative 28-page booklet that goes into depth about the group, the region and the songs. (The Vital Record, by the way, is only now getting off the ground—the website lists but two other titles in its catalog, a CD and a video by Sean Tyrell. Its admirable mission is posted on the home page, to wit: “…we’re committed to releasing music that sounds like the place on earth where it’s from. Along with fair, clear deals for the artists, The Vital Record gives a portion of any profits to local-run co-operatives and community organizations dedicated to the well-being of the people and cultures who make the music. Music is alive. The record is vital.” Gotta love ‘em.)

Juaneco y su Combo was formed in 1968 by Juan Wong Paredes, known as Juaneco. An amateur saxophone player of Chinese ancestry, Juaneco made his living as a brick-maker. But when his son Juan Wong Popolizio took over the band, the senior Juan traded in his accordion for a Farfisa organ, and voila! The group suddenly found its sound augmented and enhanced by classically cheesy outpourings reminiscent of innumerable ’60s surf- and garage-style nuggets familiar to American listeners but unheard of in this hemisphere. This alone gave the music a singular sound but another major change was looming. Called Juaneco y su Conjunto in those days, the Juanecos made a living performing waltzes and polkas and rumbas for fairs and weddings in the Pucallpa region. In 1965, Juan Wong Popolizio resumed leadership of the band after returning from his mandatory military service in the capital. He had one big idea on his agenda: to electrify Juaneco’s music.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KA_ah2jgNRs

Juaneco y su Combo, ‘El Forastero’ (‘The Stranger’) from The Birth of Jungle Cumbia

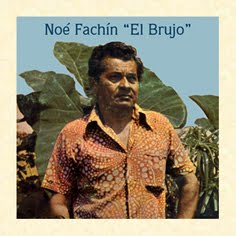

Following the 1976 plane crash that killed five original members of Juaneco y su Combo, a compilation album, recordando al ‘Brujo’ fachin, was released featuring songs the great guitarist-songwriter Noé Fachín had recorded with Juaneco y su Combo. In keeping with Fachín’s legend, one Peruvian blogger refers to him as The Sorcerer in his review of the album. Side A: ‘El pelejito bailarin,’ ‘Muraya,’ ‘El Brujo,’ ‘San Juan ’75,’ ‘Noche tropical’ and ‘Buscando tu amor’; Side B: ‘El Pinochito saitarin,’ ‘Chica linda,’ ‘Ritmo alegre,’ ‘El bagazo,’ ‘La tragedie de Rosendo,’ ‘Región oriental.’

Thus did Juaneco Jr. bring the band’s simple dance party sounds into the emerging zeitgeist: driving electric guitars instead of acoustic folk stylings, in addition to that roller-rink Farfisa supplanting the accordion. When he needed not merely a great electric guitarist but a musician of vision, he knew where to turn, enlisting Noé Fachín Mori on lead guitar. Known as “El Brujo” (“The Witchdoctor”) for his penchant for dabbling in Amazonian pharmaceuticals, Fachín, then already in his 40s, had been working as a public school teacher and moonlighting as a criollo guitarist. His gift for driving melodic hooks defined and solidified the Juanecos’ wailing, psychedelic sound—a critic at the Spanish-language blog of the fanzine Sótano Beat wonders, in a variation on the Robert Johnson legend, whether Fachín’s superior musicianship might not have a two-pronged origin, stemming in part from his experiments with Ayahuasca (a psychedelic brew comprised of various plant infusions prepared with a South American wine made from the Ayahuasca vine) and, not least of all, an unholy pact made with the dreaded Tunche in order to become famous. The Tunche is the legendary owner of the dark Amazon, described by Ningun Comentraio in the Backpacking Peru blog as “a mythological animal, a possessed soul that is present through sound, as a whistle of the bird. They say that in the forest you should not walk alone… It is much better if we know where to walk or where we are going in the jungle, because the Tunche only attacks people who are lost and confused; just listen to the whistle, which means that death is approaching. They also say that when a person is very ill or a fate toward death, the Tunche whistles, attracting his next victim.”

The members of Juaneco y su Combo listened to short wave radio transmissions and picked up Colombian cumbia and Brazilian carimbo, integrating these and other exotic sounds into something as otherworldly, sensuous and mysterious—and irresistible–as the Amazon jungle itself.

Identifying comfortably with their indigenous neighbors in Pucallpa, which boasted a progressive-bordering-on-revolutionary outlook for the time and place, Juaneco y su Combo appeared on stage (and on album covers and in photos) in the traditional dress of the Shipibo Indians (in Pucallpa, the majority of residents are of Shipibo descent), and further incorporated both the sounds and the lore of the inner jungle in their music. “They think of it as their culture, even though they are not Shipibo,” says Olivier Conan, whose Brooklyn, NY-based Barbés Records first re-introduced Juaneco on Volume 1 of the much-lauded Masters of Chicha series inaugurated in 2008. “In the grand scheme of Peruvian cumbia, Juaneco is seen as one of the originators. It is a very important part of their whole music.” The lyrical content particularly links Juaneco y su Combo to the Shipibo jungle environment. The lyrics engage native Indian themes, often referencing the forest and its folklore. (Note: Chicha and jungle cumbia are interchangeable terms, except for the former being named after a corn-based liquor favored by the Incas. Both refer to a style of music inspired by Columbian cumbias but employing the distinctive pentatonic scales of Andean melodies and some Cuban guajiras along with the surf guitars, Farfisa organs, Moog synths and wah-wah pedals common to ‘60s American rock ‘n’ roll.)

Loose, rangy, sensual, and untamed, the group’s earliest IMSA recordings, as captured on The Birth of Jungle Cumbia, became a sensation, a micro-regional answer to the rock ‘n’ roll that was sweeping the world, but one that, by design or by chance, happened to sound fresher and more primitive than almost anything else being produced on the planet.

[The raw emotion and unabashedly down-and-dirty qualities of these records more than make up for their low-rent production. The recordings on The Birth of Jungle Cumbia are taken from exceptionally rare vinyl copies, as the masters were long ago lost or taped over. Minor audio flaws are entirely eclipsed by the glorious passion and effervescence of the songs themselves.

Juaneco y su Combo, ‘Caballito Nocturno’ (‘Night Horse,’ n ode to an Amazonian creature of legend, a woman who turns into a centaur and is ridden and whipped by the devil himself, all as punishment for salacious deeds), from The Birth of Jungle Cumbia

Juaneco y su Combo, ‘La Incognita’ (‘The Unknown’)

The song “Ya Se Ma Muerto Mi Abuelo” (from Masters of Chicha Vol. 1) blends themes of traditional food and death, comedy and tragedy, as a way of transforming the band’s plane crash calamity. The lyrics recount the many ways their ancestors died from drinking masato (a fermented yucca drink) to eating suri (a little worm prepared as a Shipibo delicacy). From the same disc, “Me Robaron Runamula” describes the story of a Shipibo mythological creature, one who is half mule and half woman. “Ayahuasca” illustrates some of the group’s creative out-there style. A precursor to some hip-hop aesthetics, a woman’s voice repeatedly says “give me more” of the psychedelic tea.

Juaneco y su Combo, ‘Mujer Hilandero,’ from Barbés Records’ The Roots of Chicha compilation. This was the group’s first hit in Peru. Joan Baez has recorded a version of it in Portuguese.

“Mujer Hilandera” (or “The Weaver” in English) was Juaneco’s first hit in Peru. “It’s a complete cover of a famous Brazilian song,” says Conan. “Everyone in Brazil knows it. But nobody in Peru knows it is Brazilian. If you tell Peruvians it’s a Brazilian song, they look at you like you’re crazy. It was in a movie that got a prize at Cannes. Joan Baez sang it in Portuguese.”

Listen to the agitated, hip-shaking rhythms of the opening track on The Birth of Jungle Cumbia, “Caballito Nocturno” (an ode to an Amazonian creature of legend, a woman who turns into a centaur and is ridden and whipped by the devil himself, all as punishment for salacious deeds). The grungy organ hook and the reverb-heavy guitar need no lyrical assistance in telling this cautionary tale. Appreciate the striking beauty of “El Forastero,” a strutting Cuban bolero composed by bandleader Juaneco, one of the rare songs by this group to add lyrics for more than simple vocal textures: “I wander looking for a love/ Who knows how to understand me/ Because I’m a stranger/ Who’s very understanding/Then, when I find that love/ I’ll stay with you forever.”

Juaneco y su Combo, ‘Perdido en el Espacio’ (‘Lost in Space’) from The Birth of Jungle Cumbia

“Lamento en la Selva” provides a frightening, tragic bit of foreshadowing. This mostly lyricless song was written as a lament for the lives lost in the famous 1971 LANSA Flight 508 that disintegrated in the air after being struck by lightning, killing 92 of the 93 passengers bound for Pucallpa. Juaneco Jr.’s siblings–a sister and a brother–were among the fatalities. (Later, the astonishing story of Juliane Koepcke, the sole survivor, became the subject of Werner Herzog’s 2000 made-for-TV documentary Wings of Hope. While scouting locations for his film Aguirre, Wrath of God, Herzog had been booked on the fatal LANSA 508 flight, but a booking foul-up landed him on another flight instead.After some 20 years of searching for the press-shy Koepcke, Herzog located her in Munich and she cooperated in the documentary.).

Juliane Koepcke, the only surviver of the 1971 LANSA Flight 508 that was struck by lightning and disintegrated in the air. Ninety-two other passengers and crew perished. Director Werner Herzog told Koepcke’s story in his 2000 documentary Wings of Hope. She is seen here in a still from the video, sitting next to a row of the plane’s seats found amidst the crash rubble in the Peruvian jungle. The crash also claimed the lives of the sister and brother of Juan Wong Popolizio, who had taken over the leadership of the band founded by his father, Juan Wong Paredes (aka Juaneco), Juaneco y su Combo. The band remembered the LANSA 508 victims in a song, ‘Lamenta en la Selva.” Four years later, five members of the Juaneco y su Combo nonet would die when their plane crashed en route home from a concert.

Werner Herzog’s Wings of Hope, a documentary about Juliane Koepcke—now Juliane Diller, a German biologist—and how she survived the crash of LANSA Flight 508 on December 24, 1971. The complete documentary has been uploaded to YouTube in seven parts by RaleighArtist. This is part one, a ten-minute segment.

As noted above, that tragedy would not be the only airline disaster to strike the Juanecos. On May 2, 1976, five of its members, including Noé Fachín (the others were Jairo Aguilar, Edilberto Vasquez, Wilberto Murrieta and Walter Dominguez) died when their plane crashed while en route back from a concert. Though Juan Wong was not on the plane and continued the band for many years, he has since passed away. Now headed by his son Mao Wong Lopez, Juaneco y su Combo is undergoing a renaissance at home and abroad due to renewed interest in chicha. Even so, it’s not the same magic, and without Fachín, in particular, the sound is less edgy and unpredictable.

All of which makes these stunning early recordings even more important. With 18 tracks total, coming from a full-length LP and a handful of singles all recorded in the early 1970s, it’s the earliest Juaneco y su Combo work ever reissued, and the most daring. Says The Vital Record label head David Aglow, “This album was never really heard by most Peruvians. This is, more than anything, a lost album.” Though the group did achieve national popularity in Peru with its more heavily produced later albums, those recordings can’t match the energy and inspiration of the group as it was constructed before the 1976 air tragedy. “It was probably too raw for people outside the jungle at that time,” Aglow says of this music. “In our opinion, that’s what makes it sound so good to us now.”

from recordando a Fachín, ‘El Brujo,’ Juaneco y su Combo

While later chicha groups were connected to the Peruvian highlands and gelled in the urban areas, Juaneco y su Combo was distinctively Amazonian and rural. Conan considers them to be one of chicha’s great precursors. Starting in the 1950s, and continuing through the ’70s, the Peruvian political leadership sought to distinguish its national identity from its early Spanish influences by iconicizing folkloric traditions such as the Andean panpipes and the Afro-Peruvian urban sound. Chicha musicians rarely enjoyed official recognition, remaining marginalized by the Peruvian upper and middle classes. No, it is not the group it was before the fateful 1976 plane crash, but credit the current members of Juaneco y su Combo for carrying on the tradition of its founders, still stirring audiences with their spirited, topical songs and honoring the legacy of a truly great band. The release of The Birth of Jungle Cumbia and Masters of Chicha, Vol. 1 is a signal event in recent music history. –-David McGee

The Vital Record’s trailer for The Birth of Jungle Cumbia

The Birth of Jungle Cumbia is available in CD or mp3 form from Amazon and directly from The Vital Record website as well. Barbés Records’ Masters of Chicha Vol. 1 featuring Juaneco y su Combo is available at Amazon.

Sources: “An Album Lost in the Amazon: Juaneca y su Combo’s Groundbreaking Early Jungle Psychedelia Recordings are Revived,” World Music Newswire; “Amazonian Hallucinogens, Wah-Wah Guitar, a Plane Crash: Juaneco y su Combo Kicks off the Masters of Chicha Series,” Rock Paper Scissors