Written, directed, produced, edited and music composed by Charles Chaplin

Cinematography: Roland Totheroh

CAST:

The Man: Carl Miller

The Woman: Edna Purviance

The Child: Jackie Coogan

A Tramp: Charles Chaplin

Professor Guido/Night Shelter Keeper: Henry Bergman

Pickpocket/Guest/Devil: Jack Coogan Sr.

Flirtatious Angel: Lita Grey

The Kid as a Baby: Silas Hathaway

Tough Cop: Walter Lynch

Priest: Edgar Sherrod

Baby in Carriage: Baby Wilson

Lady with Baby Carriage: Edith Wilson

Policeman: Tom Wilson

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUvdSjDbvRA

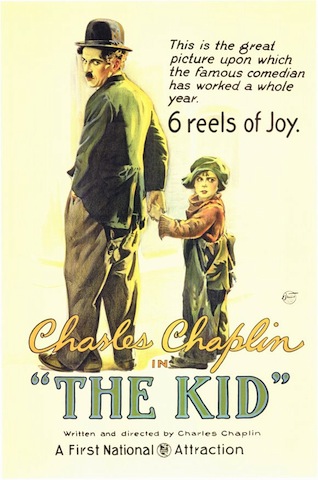

Charlie Chaplin made films far more famous and influential than his 1921 masterpiece The Kid, but none richer in defining the character of his beloved Tramp (beloved by its creator as much as by his audience—his child bride, actress Lita Grey [who had a bit part in The Kid before Chaplin cast her to star in The Gold Rush, only to impregnate and thus sideline her before shooting began] once said the person her former husband loved most was in fact not his wife but the Tramp). In doing so, Chaplin also revealed much about the ghosts that haunted him still from a childhood marked by an absentee father, an emotionally unstable mother and the attendant horrors of living in abject poverty that sent him to a workhouse twice before he was even nine years old. Dickens couldn’t have conceived of a more squalid or debasing existence for a lad. (Perhaps this is the place to note that the absentee father’s connections were responsible for young Charlie landing his first show business job, as a member of the Eight Lancashire Lads clog dancing troupe, and that his mother “imbued me with the feeling that I had some sort of talent,” as he himself wrote.) At the same time, The Kid also allows Chaplin’s audience a glimpse of the tender heart and scrappy attitude that the deprivations of his childhood only enhanced and which would come to the fore as the most endearing qualities of one of cinema’s most popular and enduring creations.

The Tramp’s—and Charlie’s—sense of being an outsider is emphasized in the first glimpses of the Tramp in The Kid. He’s casually strolling along the street, minding his own business, when objects suddenly start raining down on him, covering his dilapidated suit in dust as he hops about in vain trying to avoid what turns out to be the detritus produced by sloppy construction workers overhead. Briefly glimpsed, they offer nothing in the way of apologies or help—he is, as he so often is and would be, and had been for so long in his youth, on his own.

Written, directed, produced and with music composed by Chaplin, The Kid begins with a title card that could not be a more succinct description of the story about to unfold and of the emotions the Tramp’s humanity stirs: “A picture with a smile—and perhaps, a tear.” In a clear stab at moral hypocrites, the opening scene shows an unmarried mother (played by Chaplin favorite Edna Purviance)—“The woman—whose sin was motherhood” another title card indicates—leaving a charity hospital with her babe wrapped in swaddling clothes as a nurse and custodian fix disapproving stares upon her. In a bit of heavy handed symbolism, Chaplin inserts the image of Christ carrying his cross before showing Purviance, alone and looking frightfully wary, taking a seat on a park bench. The scene then cuts to “The Man,” as per the title card, and the child’s father, a bohemian painter, is seen in his house, dejectedly staring at a photo of Purviance as an older gent critiques his latest canvas. He accidentally knocks her photo into his fireplace, quickly retrieves it, hesitates, then places it back on the coals and stirs them up a bit to stoke the fire, which quickly consumes the image as the scene irises out.

In the meantime, a distraught Purviance, upon seeing a happy couple emerge from their church wedding, carefully deposits the newborn inside a fancy car parked outside a swanky mansion, kisses it goodbye and runs off. Enter a couple of hijackers who steal the car, only to discover, upon taking a cigarette break in a deserted alleyway, a crying baby in its back seat. One of the thugs leaves the baby on the ground next to a trash can and the pair drive away.

Enter the tramp unawares, the fingers of his gloves having worn away as he studies the array of cigar and cigarette butts in his tin holder. As he puts himself together—straightening his tie, dusting off his jacket—he spots the baby, then places it in a carriage he sees on the street behind him, telling the lady who comes rushing towards him, “Pardon me, you dropped something.” She gives him what-for and he takes the baby back. As he returns it to the spot where he found it, a scowling policeman materializes. The Tramp recovers the baby and goes his own way, with a quick, anxious look back at the cop as he does. On another side street, he asks an older man to hold the baby while he fixes his shoe, then, after placing the infant in the fellow’s arms, runs swiftly away. Ultimately, after a bit more business, the baby winds up in the Tramp’s care, and as is his wont, he makes the best of an unfortunate situation and takes him in as his own after finding a note tucked away in his blanket, written by the mother, asking that her offspring be cared for in her absence. The mother, meanwhile, has had second thoughts and rushes back to the mansion, desperately hoping to find her baby still in the car’s back seat, but to no avail.

Back at his home, the tramp rigs up a teapot for the baby to nurse from, practices folding diapers and cuts the bottom out of a wicker chair, presumably for it to serve as the baby’s toilet. Having only the bare necessities at his disposal, the Tramp exhibits the ingenuity and cleverness that defined his survival instincts in a world with all its forces seemingly aligned against him and his kind. He would not be traduced or constrained by his circumstances, but was all about not merely surviving but living with all the dignity and grace the affluent society would have denied him.

As is noted at the website The Talkie & the Tramp: Charlie Chaplin Stays Silent in the Machine Age: “In the Tramp, Chaplin found a vehicle for the expression of an authentic experience. The substance of this experience was the fulfilled desire for physical freedom in a society structured to obstruct ease of mobility. Charlie’s ability to move so easily and with such authenticity resonated with his audience’s frustration at the restriction of lives governed by social propriety, the class structure and, especially in the thirties, the regime of mechanization.”

Five years pass and the baby is now the title character, portrayed with preternatural ease by seven-year-old Jackie Coogan, who would become cinema’s first child star upon the release of The Kid. The Tramp and The Kid are functioning as more than parent and child; they are outsiders, orphan and tramp, working in concert to get a leg up—The Kid is expert at breaking windows with rocks, The Tramp follows him in as a glazier offering his repair services. Again from The Talkie & The Tramp: “The difference between them is that while Charlie is outside the social structure by choice-he never laments his downfall or otherwise provides any clue of a life different from his present one-the Kid is outside because he was dumped there. Furthermore, society wants him back. Dramatic development in the film stems from an episode during which Charlie shows a doctor the note the Kid’s mother left with him; from this point on, various forces gather against Charlie to reclaim the Kid and place him in a ‘proper’ home. The collective efforts of the doctor, the orphanage authorities, the newspapers and even the manager of a flophouse in which Charlie and the Kid seek refuge all converge on the duo. They are trapped in a pattern of capture, escape and recapture.”

While The Kid and The Tramp’s relationship has been developing, the mother has become a successful opera singer; in her spare time she does charity work for disadvantaged children, hoping to find her lost son. At a society event she engages in a bittersweet, joyless reunion with the child’s father, who expresses regret at the pain he’s caused her, before making a doleful exit. Through a doctor friend she learns of her child’s whereabouts, who calls the authorities to retrieve the lad and return him to his mother. Thus begins one of the most wrenching scenes in film history. The cops burst in on the two, and a seriocomic struggle ensues, with The Tramp slugging it out with the intruders as The Kid cries out for him. The Tramp doesn’t prevail, but as The Kid is taken away in a paddy wagon, The Tramp scrambles through an open window and follows the wagon down the street, The Kid, arms extended, screaming and crying for The Tramp all the way, until The Tramp is close enough to jump down into the wagon bed, cold cock the magistrate guarding The Kid and leap from the wagon with his charge after the driver comes to a stop. As it has throughout the film, humor comes at the most unexpected moments. Here, the driver and The Tramp engage in a stare-down, The Tramp makes a move as if to charge the driver, the driver runs a few yards up the road, turns, stares at The Tramp, The Tramp makes another move as if to charge at the driver, the driver runs away again, stops, looks back, The Tramp fakes another charge, and off the driver sprints. The added element tugging at the audience’s heart here is the keening, minor key score Chaplin composed for the movie in 1971.

Twelve-year-old Lita Grey, soon to be Mrs. Charlie Chaplin, as the Flirtatious Angel on the set of The Kid with Charlie Chaplin

Alas, a reward has been posted for the child’s return, so when The Tramp and The Kid check into a flophouse for the night, the proprietor recognizes The Kid from the flyer and this time the authorities succeed in reuniting mother and child. The Tramp returns home alone, only to find himself locked out of his own house. Exhausted, he falls asleep on the doorstep and wanders into a bizarre dream sequence the meaning of which Chaplin scholars are still debating. Various characters seen earlier in the film reappear adorned with wings—even the dogs have wings, and so does The Kid—everyone but The Tramp, in fact, has wings The Kid takes his mentor shopping for a pair, but without much success: something’s not right with the fit, they itch, they constrain his movements. They reign him in as society could not. The scene becomes more confused and more sinister, when a figure wearing a devil mask enters as “Sin” and sends the “Flirtatious Angel” (twelve-year-old Lita Grey, who, three years later, would become Lita Grey Chaplin and bear Charlie two sons, Charlie Jr. in 1925 and Sydney Chaplin in 1926, the latter child coming in the same year the Chaplin couple divorced) to temp The Tramp. The angel’s lover then attacks The Tramp, a fight ensues, The Tramp tries to fly away but a winged cop shoots him down. As The Tramp’s life ebbs away on his doorstep, The Kid kneels over him, then disappears. A policeman props up The Tramp in the doorway and tries to shake him into consciousness, at which point The Tramp is awakened from the dream by a real policeman shaking him to, helping him to his feel, then leading him away—not to jail but to The Kid’s mother’s well appointed home, where he is reunited with The Kid and welcomed in by the mother. Her closing the door behind him as “The End” flashes on the screen is a moment rich in symbolism and ambiguity that resonate throughout the rest of Chaplin’s work in the ‘20s and ‘30s. Much has been made of Chaplin’s affection for young Coogan on screen, in light of The Kid beginning production only a few months after the death of Norman Spencer Chaplin, the filmmaker’s firstborn son by his first wife, actress Mildred Harris. Born July 7, 1919, the baby was malformed and lived only three days.

A great trailer for The Kid

Moreover, The Kid is rife with all sorts of compelling contrasts in The Tramp’s relationship with authority figures, genteel society and even other outsiders hewing to a markedly less humanistic code, if any code at all, than did Chaplin’s complex creation.

As per The Talkie & The Tramp:

In addition to the forging of a deep emotional bond with the Kid, this film also presents an aspect of the Tramp’s development having to do with his increased dealings with society’s structure of authority. The two seem related. Certainly, the Tramp had encounters with the police in the short films, but he usually he evaded the officer and quickly ended the incident. The police presence in The Kid is of a greater degree of intensity: there is literally a policeman around every corner. There are also the imposingly Victorian “country doctor” and the orphanage authorities.

The Tramp does not have direct contact with the gangsters who dump the Kid in the alley, but their actions do affect him. The presence of the gangsters serves to indicate a difference between the Tramp and the outlaws. Both are on the outside. The Tramp, though, is not so removed as to be “above the law.” The authority structure wears him down and takes from him the child he loves, but that does not cause him to abandon that love.

Charlie gained resilience in his first long film. He had always been able to bounce back, but the films of the twenties matched his physical resilience with emotional sustenance. Perhaps because it is a transitional film, the ending of The Kid is not completely satisfying–does the Tramp marry the Lady? or does he only get visiting rights? These questions having to do with the Tramp’s ability to fit into the social structure remained open for future films to address.

The Tramp and The Kid ply their trade

Chaplin’s next film, 1923’s A Woman of Paris, starred Edna Purviance in a role Chaplin hoped would make her a top-tier star, but she didn’t play opposite her director: the male lead was Carl Miller. Written, directed and produced by Chaplin, it was the first of his films in which he did not appear on screen. A critical success but a box office failure, it was the first feature film released by the company Chaplin co-founded, United Artists. After its initial release Chaplin withheld it from distribution for more than 50 years. Chaplin eventually re-edited it and in 1976 replaced the original score composed by the flamboyant, iconoclastic American pianist Louis F. Gottschalk with a new score of his own, which was the final completed work of his 75-year-career.

A Woman of Paris’s fate would not be repeated. It set the stage for The Tramp’s glorious return in 1925’s The Gold Rush, which would be followed by four consecutive Chaplin cinematic triumphs: The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936, the Tramp character’s final appearance on screen) and his first “talkie,” The Great Dictator (1940). -–David McGee

Selected Short Subjects

Charley at The Beach (1919) & Felix in Hollywood (1923)

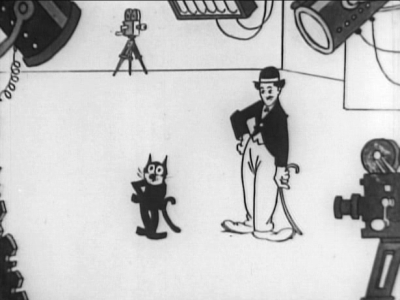

Silent cartoon classics featuring Charlie Chaplin by Pat Sullivan & Otto Messmer

In 1918 and 1919, Pat Sullivan created a series of 14 cartoons starring Charlie Chaplin getting into adventures all over the globe (the first, in 1918, was titled “How Charlie Captured the Kaiser” and depicts him crossing the ocean in a tub, defeating a German submarine and conquering “Huns right and left”). Almost all of these have been lost, but a handful have been saved by collectors. One of these is “Charley at the Beach,” from 1919. At a beachside refreshment counter, Charley orders a “raspberry highball” and faces an effeminate waiter. Back on the sand, Charley shuttles between dressing rooms to peer at the girls inside until a policeman chases him off. This surviving print is two minutes shorter than the original version, a copy of which has never surfaced. Sullivan and his lead animator, Otto Messmer, of course went on to create the legendary Felix the Cat, like Chaplin an outsider and some claim modeled after Chaplin’s Tramp character.

“Felix in Hollywood” is a 1923 short featuring Felix the Cat. In the episode, Felix goes to Hollywood and meets Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Will Hays, Snub Pollard and Ben Turpin, in the first animated cartoon to feature caricatures of Hollywood celebrities. It was named #50 of The 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time in a 1994 survey of animators and cartoon historians by Jerry Beck, making it the only Felix the Cat cartoon on the list. (Source: Wikipedia)