(Irving Townsend [1920-1981] was a record producer and author revered for steering Miles Davis’s 1959 masterpiece, King of Blue, the best selling jazz album of all time. A former bandleader, he joined Columbia Records as an advertising copywriter. At Columbia he befriended legendary producer George Avakian and persuaded Avakian to let him assist on recording sessions. By the mid-1950s he was a full-time producer. His lengthy credits range across several genres and include projects with Mahalia Jackson, Jimmy Rushing, Doris Day, Flatt & Scruggs, Frankie Laine, Leonard Bernstein, Billie Holiday, Andre Previn, Dave Brubeck and others. In 1960 he teamed up with Duke Ellington for what became a fruitful professional partnership that included his production of the bandleader-composer’s imaginative take on Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Suite. In his memoir, Music is My Mistress, Ellington described Townsend as “a very sensitive musician. He plays clarinet in a trip symphony, one of those groups that includes doctors, lawyers and accountants who worked their way through college as professional musicians and who like to get together once or twice a week to try out their chops. He is now executive producer for Columbia Records on the West Coast.

“As an a. and r. man he is wonderful. He has full knowledge of the mechanics of the business, and he also has such understanding that he seems to know what the artist is trying to get without going into long-winded rigamarole of rules and regulations, and without being swayed by what some other artist did last week. I love him and his whole beautiful family. We are indebted to him for having produced many of our favorite and most satisfactory records.”

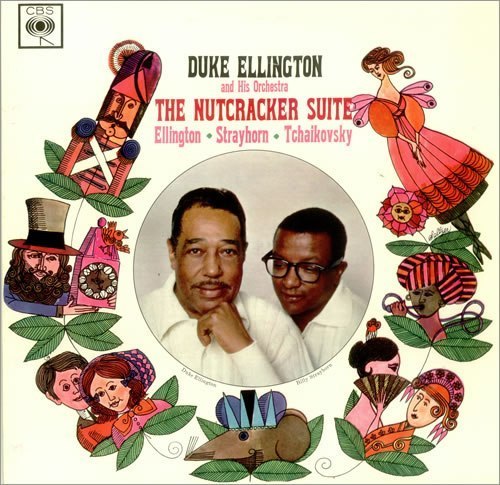

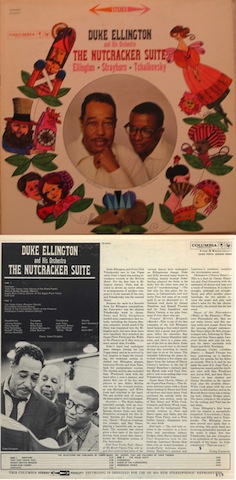

In his liner notes published on the back cover of the 1960 Columbia release of Ellington-Strayhorn’s The Nutcracker Suite, Townsend discusses the origins of the album project and offers a track-by-track description of the Ellingtonian changes to the great Russian composer’s ballet score. The first paragraph, however, is pure fantasy: in order for Duke Ellington to have met Tchaikovsky in Las Vegas, the two would have to convened before Tchaikovsky’s death…in 1893, which would have been six years before Ellington’s birth and twelve years before Las Vegas itself was established as a railroad town. Perhaps Townsend’s misspelling of the Russian’s name as Peter Ilich instead of the correct Pyotr Ilyich was his way of letting us in on the joke.)

Duke Ellington and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky met in Las Vegas while Duke’s band was setting attendance records at the Riviera Hotel. For the first time in Ellington history, Duke had decided to devote an entire album to arrangements of another composer’s works instead of his own, and Tchaikovsky was the natural choice.

Because the suite is a favorite form for Ellington composition, the Nutcracker was the obvious Tchaikovsky work to choose. Duke and Billy Strayhorn needed some reassurance that nobody, including the famous Russian composer, would mind if the Suite was translated into the Ellington style, but once those fears were banished, they attacked the Sugar-Plum Fairy and the Waltz of the Flowers as if they were no more sacred than Perdido.

Duke Ellington & His Orchestra, ‘Overture’ from The Nutcracker Suite

Duke’s band had undergone some changes during his Las Vegas stand, and as he arrived in Los Angeles to begin the recording, the trombone section included two Ellington alumni, Lawrence Brown and Juan Tizol, back for postgraduate courses.The rhythm section also included Sam Woodyard, back with the band after a year’s absence, and Aaron Bell, one of the fine bass players in jazz. Eddie Mullins was new in the trumpet section, as was Meringuito, and Willie Cook had returned to the band. The sax section and, of course, the piano player, were unchanged.

Overture — The Suite begins, naturally enough, with an overture based on the first of many famous themes Duke and Billy Strayhorn arranged for this album. Soloists are Paul Gonsalves, “Booty” Wood on trombone con plunger, and Ray Nance, playing a beautiful solo on open horn. The ensemble last chorus gives a first taste of the kind of driving band sound that characterizes the Ellington version of The Nutcracker.

Toot Toot Tootie Toot (Dance of the Reed-Pipes) — You will by now have noticed that the titles of the various dances have undergone an Ellingtonian change. Duke and Billy devoted many hours to retitling, mainly because Duke, having adapted the Suite to his style, felt the titles were also in need of “reorchestrating.” (The full title for this piece, for instance, is Caliopatootic toot toot tooti Toot, but none of us could spell it, so we shortened it). It featured reed duets by Jimmy Hamilton and Russell Procope and by Paul Gonsalves and Harry Carney, a toy pipe foursome if ever there was one.

Duke Ellington & His Orchestra, ‘Chinoiserie (Chinese Dance)’ from The Nutcracker Suite

Peanut Brittle Brigade (March) –- This is one of the fine examples of the full Ellington band turning a four-sided march theme into a great jazz performance. After the ensemble, Ray Nance and Jimmy Hamilton take solos, and there is a piano solo, one of the few in this Suite. Duke devoted so much time to the band during this recording he rarely had time to sit at the piano. The ensemble following the piano interlude featured a five-octave sax figure from the bottom of Harry Carney’s baritone to the top of Jimmy Hamilton’s clarinet, and, the March ends with Paul Gonsalves’ solo to an ending that even Tchaikovsky could hear.

Sugar Rum Cherry (Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy) — This famous delicacy opens with a drum figure leading to Harry and Papul on baritone and tenor saxes. Paul continues the melody while the Ellington pop section, made up of Ray Nance and Willie Cook, trumpets, and Booty Wood, trombone, wail the background. The melody returns to Paul and Harry again and fades, and the Sugar Plum Fairy, now a West Indian beauty, disappears into the cane fields.

Entr’-acte – The entr-acte returns to the overture in a freer form and introduces Johnny Hodges, while Harry Carney and Paul Gonsalves join in the build-up. Lawrence Brown then takes over on muted trombone, a wonderfully welcome sound. Jimmy Hamilton’s clarinet and Lawrence’s trombone complete the intermission music.

Chinoiserie (Chinese Dance) – This is a duet by Jimmy Hamilton and Paul Gonsalves with the assistance of drums and bass and a touch of trombones. It is played straight, although not straight-faced, and after another piano interlude, the two soloists reverse the music and play each other’s solos for the last chorus. Naturally, the pianist has the last word.

Dance of the Floreadores (Waltz of the Flowers) – Whatever Floreadores are, they are not waltz lovers, and this one-time waltz now jumps. Booty has the opening plunger statement. Ray Nance plays the first plunger trumpet solo, followed by Hamilton and then Nance again. Lawrence Brown sails into his solo, and the danse concludes with Booty and Britt Woodman.

Duke Ellington & His Orchestra, ‘Sugar Rum Cherry (Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy)’ from The Nutcracker Suite

Arabesque Cookie (Arabian Dance) – Russell Procope has been practicing on a bamboo whistle for months for his debut on records. This is it, and he has made the most of it. Juan Tizol, a tambourine expert, sets the rhythmic color with Sam Woodyard and Aaron Bell, and then Harry Carney on bass clarinet and Jimmy Hamilton on the regular kind, play the Arabian Dance. Willie Cook plays with the reed section on this number, and as the Moorish flavor turns into a swinging beat, Johnny Hodges plays. The dance returns to the original for the ending, and Tizol has the last shake.

Duke Ellington’s first brush with the classics is successfully completed. It is a tribute, I think, to Duke and Billy and to Tchaikovsky. The Ellington forces have proved, once again that in any setting, this great band and its strong personality pervade all the music it plays. But that Tchaikovsky has also triumphed is an indication of the perennial strength of his music. As Duke commented, “That cat was it.”

Suite Perspective

By Steve Schwartz

DUKE ELLINGTON: THREE SUITES

Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker Suite (orch. Ellington & Strayhorn)

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suites 1 & 2 (orch. Ellington & Strayhorn)

Ellington-Strayhorn: Suite Thursday

Duke Ellington Orchestra/Duke Ellington

Sony/Columbia Jazz (2008)

I never knew how Ellington got the nickname “Duke” until I saw him live. Then I understood immediately: this was the most elegant fellow I’d ever encountered. I came to jazz fairly late, in grad school, and even now I feel I’m playing catch-up. I don’t know nearly enough, even after more than twenty years of serious listening. So don’t expect me to talk knowledgeably about Ellington’s career or his connections to Calloway’s Cotton Club band or to spout Brunswick matrix numbers. What I think I can talk about is the small part of Ellington’s output that touched classical music.

Many classical composers had incorporated jazz and proto-jazz elements in their work, going all the way back to Debussy’s graceful versions of ragtime. However, it took George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue to galvanize composers and to get artists to take jazz as seriously as they took Brahms. I’m not calling Gershwin’s work the best amalgam of jazz and classical or even calling it jazz, in the sense in which most present-day aficionados use the word. I talk strictly about its impact. Gershwin became an archetype which many jazz musicians found enormously attractive. J. P. Johnson forsook a career as band leader and one of the great jazz pianists to devote himself full-time to composition based in black dance-band music. Ellington himself–deploring what he called the “lampblackisms” of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess–was nevertheless inspired to Black, Brown, and Beige and a career which raised displays of solo virtuosity to mini-concerti, the “mood” piece to concert suite, and the vocal to “sacred concert.”

All of these things have encountered critical resistance, I believe, for the following reasons: Critical ignorance leads the rest. Classical critics don’t usually have a firm idea of jazz tradition or procedures, and they tend to seriously undervalue both. Racism probably entered into the initial critical reaction, but it doesn’t explain the current resistance. I believe most classical critics are keeping Ellington’s work at arms’ length not because he’s black, but because they just don’t get it. They don’t get it because they don’t listen to jazz enough, and they don’t listen to jazz because they don’t take it seriously. They don’t take it seriously because they haven’t listened seriously to enough of it – a circle of ignorance. Furthermore, a great deal of Ellington’s work resulted from a collaboration between himself and the composer and arranger Billy Strayhorn. Consequently, critics don’t know how to assign credit: did Ellington or Strayhorn come up with this particular wonderful thing? Testimony from various sources doesn’t help, since almost every witness says that Ellington and Strayhorn’s techniques were identical. To finish a piece on deadline, Ellington would work on a passage, wake up Strayhorn, and catch a nap while Strayhorn took over, often in mid-measure. The fact that Ellington and Strayhorn frequently couldn’t remember who thought of what doesn’t help matters. Nevertheless, we can deal with the last problem by assigning credit to both, creating an entity known as Ellington-Strayhorn.

As orchestrators and harmonists, Ellington and Strayhorn found inspiration in Debussy and Ravel. Relatively late in his career, Ellington decided to release an album devoted to orchestrations of other composers and chose Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite–not exactly a safe choice, since many consider Tchaikovsky one of the great orchestrators.

Certainly Tchaikovsky knew how to handle strings, as the Serenade in C amply proves. However, the jazz band doesn’t normally use massed strings, rather massed winds and brass. Furthermore, the jazz rhythm section changes the orchestral balance radically, mostly because it must fight for attention among the stronger-voiced winds. The jazz rhythm section–bass, guitar, and drum kit–is far more forward in the texture than the usual discreet and widely spaced booms and dings of the symphonic percussion section. The standard rap against Ellington’s big concert works is that–compared to Tchaikovsky, Elgar, or Bartók–they don’t use strings all that well. However, one can turn this around. I know of no classical composer who uses reeds and brasses as imaginatively as Ellington. With the three works recorded here, the rap becomes irrelevant, since Ellington-Strayhorn wrote for the Ellington orchestra. The backbone of Tchaikovsky’s orchestra is the string section; the backbone of Ellington’s, the rhythm section. That is, strings dominate the Tchaikovsky sound, with winds and brass providing color. Ellington’s sound continually changes with new and surprising combinations of reeds and brass, although the bass and percussion are constants. This means that you can’t simply take Tchaikovsky’s lines straight and give them to winds. You’ve got to make them idiomatic for winds. In doing so, Ellington-Strayhorn recompose substantially, altering Tchaikovsky more than Stravinsky did Pergolesi for the Pulcinella ballet, and the work becomes more theirs than the Russian’s. They don’t just put a jazz beat behind Tchaikovsky’s ballet, although I don’t mean to imply that the jazz rhythms they come up with are routine. In transmogrifying Tchaikovsky to something idiomatic to jazz, they extend Tchaikovsky’s basic ideas and harmonies in new and surprising ways.

Gunther Schuller mused rather wistfully about the benefits of classical musicians looking hard at an Ellington score. For him, there were leaps of high imagination on every page. In Ellington’s Nutcracker, they seem to come in just about every measure. I consider this one of the great American scores, and you’ll probably never hear it at your local symphony.

Ellington gave new titles to the movements and rearranged their order, justified, I believe, by the new character of the music. The sequence in the Ellington-Strayhorn Nutcracker runs:

Overture

Toot Toot Tootie Toot (Dance of the Mirlitons, or Reed-Pipes)

Peanut Brittle Brigade (March)

Sugar Rum Cherry (Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy)

Entr’acte

The Volga Vouty (Russian Dance)

Chinoiserie (Chinese Dance)

Danse of the Floreadores (Waltz of the Flowers)

Arabesque Cookie (Arabian Dance)

The “Overture” transforms the miniature delicacy of the original to an easy lope, with some unusual syncopated counterpoint. “Toot Toot Tootie Toot” (originally titled “Caliopatootie toot toot tootie Toot”) begins with some absolutely brilliant writing for solo winds and finger cymbals, none of which comes from Tchaikovsky. When the Tchaikovsky theme appears, Ellington-Strayhorn throw in extra tasty dissonances and genuine counterpoint, taking off from jazz voicings. Ellington’s Sugar-Plum Fairy prowls through the night on the arm of a deliciously insinuating sax solo from Harry Carney. The “Entr’acte” plays with overture once again, this time allowing soloists greater opportunity for display. This might be an earlier draft of the overture, too good to throw away. “The Volga Vouty” stands out for the color Ellington-Strayhorn coax from all sorts of mutes. “Peanut Brittle Brigade” sizzles as a driving big-band number, with skirls of parallel chords from the saxophones, on the money rhythmically and pitch-wise, and a powerfbaritone sax solo from Paul Gonsalves.

At “Chinoiserie,” Ellington and Strayhorn turn in a brilliant orchestration of solo saxes, plucked chords from the bass, and a delicate percussion seasoning from drummer Sam Woodyard. This wind writing is so spectacular as to be out of most classical composers’ reach. “Danse of the Floreadores” turns the lush string writing of Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz of the Flowers” into a kaleidoscopic exploration of various wind and brass combos. The finale, in the Ellington-Tizol “Caravan” vein, boasts the reed and brass sections taking long phrases in apparently one huge breath and a fantastic solo from sax great Johnny Hodges. In all, one of the outstanding examples in all music of one great composer rethinking and re-imagining another.

From Duke Ellington’s take on Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suites Nos. 1 & 2, ‘Morning Mood’

The arrangement of Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites comes closer to typical Ellington and therefore surprises me less, although I don’t sneeze at it. The opening chords alone provide more to think about than many a symphony. Nevertheless, it seems a brilliant arrangement, rather than, like the Tchaikovsky, a magnificent recomposition. High points include the plucked bass chords from Aaron Bell, the Dreigroschenoper ensemble writing that open “Ase’s Death” as well as the range of color at each repetition of the theme, and the almost-Cubist breakup of the theme into big-band riffs and short, tasty solos from the reed soloists (Hamilton, Hodges, and Gonsalves) in “Anitra’s Dance.”

Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn’s Suite Thursday

In 1960, the Monterey Jazz Festival commissioned Ellington for a large-scale work. Since Monterey is Steinbeck country, Ellington decided to write a piece based on Steinbeck’s novella Sweet Thursday–which, in typical Ellingtonian wordplay, became Suite Thursday. The links with the prose piece seem more fanciful than literal, with “Misfit Blues” (the first movement) a musical portrait of Steinbeck himself, according to Ellington. “Schwiphti” flies fast as photons, with a punched, jagged solo from Ellington himself and fleet displays from saxophonist Gonsalves. All in all, it’s one of Ellington’s most focused large-scale efforts, despite a tendency to ramble in the third movement. It ends on a swinging Ray Nance solo (on violin, yet!), miles away from the politesse of Grappelli. I’ve heard only one other violinist (and not a jazz violinist, surprisingly) swing this hard.

The sound is typical of the way producers like to mike big bands–a little bass-heavy, apparently to put more “muscle” in the music–but it’s bearable. As for the performance, come on–it’s the Ellington band. You might as well question whether Sid Caesar’s writers were funny.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz. This review is also available at Classical.net.

The inventive Harmonie Ensemble New York, guided by arranger-conductor Steven Richman, has released a new must-have holiday album featuring a traditional rendering of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Suite and the Ellington-Strayhorn version. Click here to go to our review.