Prologue: ‘A Time To Incorporate the Past’

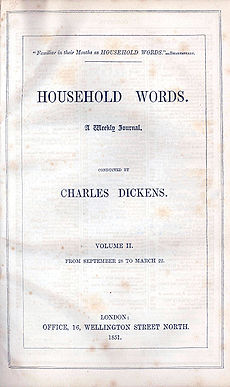

As much as, if not more than, his enduring novels, the Christmas stories of Charles Dickens are most revealing of the author’s inner life. In March 1850, at age 38, Dickens had launched a twopenny weekly, Household Words, designed to air his views on current affairs and to provide entertainment for families. He thought the weekly communications would put him in closer touch with his fans, more so than could be done with his novels, which he typically serialized as he completed chapters. Published every Wednesday from March 1850 to May 1859, Household Words featured as its main attraction during the Christmas season a lengthy short story penned by Dickens himself. During these years Dickens’s world view underwent a sea change, from youthful optimism to looming disillusion with the course of human affairs. These points of view intermingle to intriguing effect in his 1851 essay, “What Christmas Is As We Grow Older,” when the old optimism rears its head again, as at the story’s close Dickens cannot help himself from believing goodness will prevail over those trying to “tear to narrow shreds” the memory of better days and undermine the love shared among family and dear friends.

As Harry Furniss noted in a 1910 essay now available online at the Victorian Web, “The 1851 Christmas essay ‘What Christmas is, as we Grow Older’ is a transitional work, reiterating the visions in the fire of The Christmas Books of the 1840s and anticipating the moral ‘seasonal offerings’ of the Extra Christmas Numbers of Dickens’s weekly periodicals, from 1850 through 1867.”

Foggy London–“this alien city,” as it is termed by Dickens’ biographer Peter Ackroyd in Dickens–weighed on Dickens’s mind as he began his novel Bleak House, as it did when he turned his attention to “What Christmas Is As We Grow Older,” a missive written against a backdrop of great personal loss, coming a year after the deaths of his father and his daughter.

‘…the Thames which in Bleak House ‘had a fearful look, so overcast and secret, creeping away so fast between the low flat lines of shore: so heavy with indistinct and awful shapes, both of substances and shadow, so deathlike and mysterious.’ (Illustration from Punch, 1858, during London’s cholera epidemic)

Ackroyd: “There was a sense in which Dickens loved this alien city; he loved that unearthly darkness which made it a place of fantasy and a harbinger of night. This was the city that harbored all the grotesques and the monsters which he created in Bleak House, fashioning them out of the mud and dirt which fill its pages. Dickens loved the city of mist, the city of night, the city lit by scattered lights–perhaps it might be described as a form of urban Gothic, like the architecture which was even then appearing in the grander thoroughfares of London. ‘There is nothing in London that is not curious,’ Dickens once wrote. But that which was the most curious was also “the most sad and the most shocking.’ This was ‘the great wilderness of London’ in which we are able even at this late date to fix the precise places which Dickens chose to depict. The graveyard outside which Lady Dedlock dies was located at the corner of Drury Lane and Russell Street, with its entrance through Croton Court. It is now a playground for children. Krook’s Rag and Bottle Warehouse was to be found in Star yard, near Chichester Rents; at the time of writing, this whole area has been demolished to make way for new building. But, even if by a feat of the historical imagination we stand upon the same pavements and see the old buildings and gates rising up once more, they would still not be the same places which Dickens saw. For him they were emblems of a new order and thus charged with unfamiliar mystery, the whole great city becoming as extraordinary as the Thames of his vision, the Thames which in Bleak House ‘had a fearful look, so overcast and secret, creeping away so fast between the low flat lines of shore: so heavy with indistinct and awful shapes, both of substances and shadow, so deathlike and mysterious.’ One other thing ought to be remembered, too: London was as interesting to its own inhabitants as it was to Dickens himself, and there is no doubt that they were eager to see, to read, and to learn all they could about their novel circumstances in a city which was growing and changing at an unparalleled speed. It was their sensibility, for example, that encouraged the growth of a more strident melodrama in the ‘low’ theatres, in its dramatic contrasts mimicking the change and uncertainty of metropolitan life; there were new forms of comedy, too, particularly the comedy of shiftless street life, and a harsher kind of romanticism emerges, the romanticism which springs from the urban dark. The urban dark which Dickens was even now creating as he worked on Bleak House.

“By the first week of December he had finished all but the second chapter of its opening installment, but then he had to break off in order to start work on his Christmas essay for Household Words. Never was he able to free himself from the trammels of his weekly periodical and in this short piece, ‘What Christmas Is As We Grow Older,’ he established a melancholy note in his memories of the dead, and in his memories of past Christmases. ‘Lost friend, lost child, lost parent, sister, brother, husband, wife, we will not so discard you!’ But in this little seasonal vignette there is also a plea for forbearance, for acceptance and understanding of the past, this Christmas, the Christmas after the death of his father and the death of his daughter, this Christmas becomes for Dickens a time of reconciliation. A time to sit and pause. A time to cease to complain and to strive. A time to incorporate the past. This, at the end of 1851, when he was beginning Bleak House.” (Dickens, pp. 646-647)

What Christmas Is As We Grow Older

‘Welcome, all that was ever real to our hearts; and for the earnestness that made you real, thanks to heaven!’

By Charles Dickens

Time was, with most of us, when Christmas Day, encircling all our limited world like a magic ring, left nothing out for us to miss or seek; bound together all our home enjoyments, affections, and hopes; grouped everything and every one around the Christmas fire; and made the little picture shining in our bright young eyes complete.

And is our life here, at the best, so constituted that, pausing as we advance at such a noticeable milestone in the track as this great birthday, we look back on the things that never were, as naturally and full as gravely as on the things that have been and are gone, or have been and still are? If it be so, and so it seems to be, must we come to the conclusion that life is little better than a dream, and little worth the loves and strivings that we crowd into it?

No! Far be such miscalled philosophy from us, dear reader, on Christmas Day! Nearer and closer in our hearts be the Christmas spirit, which is the spirit of active usefulness, perseverance, cheerful discharge of duty, kindness, and forbearance! It is in the last virtues especially that we are, or should be, strengthened by the unaccomplished visions of our youth; for, who shall say that they are not our teachers, to deal gently even with the impalpable nothings of the earth!

Welcome, old aspirations, glittering creatures of an ardent fancy, to your shelter underneath the holly! We know you, and have not outlived you yet. Welcome, old projects and old loves, however fleeting, to your nooks among the steadier lights that burn around us. Welcome, all that was ever real to our hearts; and for the earnestness that made you real, thanks to heaven!

The winter sun goes down over town and village. A few more moments, and it sinks, and night comes on, and lights begin to sparkle in the prospect. In town and village, there are doors and windows closed against the weather; there are flaming logs heaped high; there are joyful faces; there is healthy music of voices.

Welcome everything! Welcome alike what has been, and what never was, and what we hope may be, in your shelter underneath the holly, to your places round the Christmas fire, where what is, sits openhearted!

Of all days in the year, we will turn our faces toward that City upon Christmas Day, and from its silent hosts bring those we loved among us. In the Blessed Name wherein we are gathered together at this time, and in the Presence that is here among us according to the promise, we will receive, and not dismiss, the people who were dear to us!

The winter sun goes down over town and village; on the sea it makes a rosy path, as if the Sacred Tread were fresh upon the water. A few more moments, and it sinks, and night comes on, and lights begin to sparkle in the prospect. In town and village, there are doors and windows closed against the weather; there are flaming logs heaped high; there are joyful faces; there is healthy music of voices. Be all ungentleness and harm excluded from the temples of the household gods, but be those memories admitted with tender encouragement! They are of Time and all the comforting and peaceful reassurances; and of the broad beneficence and goodness that too many men have tried to tear to narrow shreds.