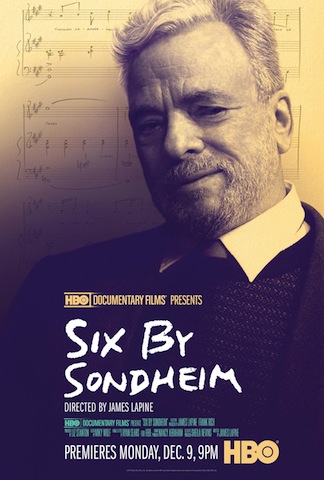

SIX BY SONDHEIM

Directed by James Lapine

HBO

Premiere: December 9, 9-10:30 p.m. ET/PT

A fascinating mix of autobiography and master class in songwriting, Six by Sondheim, premiering tonight on HBO and airing throughout December, is a riveting and highly entertaining hour and a half up close and personal encounters with the artist who could be called America’s greatest living songwriter, with little or no dissent except, perhaps, from Sondheim himself, who has arrived at age 83 (is that possible?) with as much humility about himself and his work as he exhibited in public in his early years when his lyrics for West Side Story vaulted the 27-year-old Oscar Hammerstein protégé into the front rank of the profession he had been seeking since he was introduced to live theater at age 10.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GF5O1ZcqgX0

HBO’s The Buzz on Six by Sondheim

Director (and Tony Award winner and Sondheim collaborator) James Lapine (who also served as executive producer with Frank Rich) has done such a fine job of integrating interview footage of Sondheim through the years with rare behind the scenes photos and film (most notably some silent color footage of Ethel Merman in her justifiably lauded star turn in Gypsy!) that 120 minutes flies by so fast you find yourself wanting at least an equal amount or more of this gifted artist’s story and wisdom. (One can only imagine what Mr. Lapine might have left on the cutting room floor; here’s hoping the deluxe edition of the DVD contains a wealth of special features.) The other star of the creative team is editor Miky Wolf. Sondheim’s story proceeds chronologically, but in having the songwriter tell it in his own words, Lapine and Wolf have woven the most salient parts of interviews he gave literally years apart into a narrative so seamless—and so rich in content—you aren’t always conscious of Sondheim’s reflections on the topic coming at different junctures of his life. Consider, for example, a fabulous sequence centered on the writing of the song “Something’s Coming” from West Side Story in which not a beat is lost in cutting from an interview with Sondheim today to a black and white interview shot with a much younger Sondheim. It’s set up with Sondheim remembering how, after his first show (Saturday Night) never made it to the stage owing to the producer’s death, he was offered the job of writing “just the lyrics” for West Side Story. Having always aimed to write music and lyrics, Sondheim was waffling on whether to jump in. In a notable understatement, Hammerstein told the young songwriter “that it would great experience for me because I would dealing with people with enormous talent and ability”—meaning, of course, Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and Arthur Laurents—“and I would learn a great deal through practical experience and I should not worry about the time lost not writing music. And he was right.”

Preview of Six by Sondheim, directed by James Lapine

Sondheim then discusses the character Tony’s (as portrayed by Larry Kert) pivotal “Something’s Coming” moment and how he employed baseball imagery to emphasize “Tony’s desire to move forward, to get away from his gang life. He knows there’s something around the corner that’s going to make his life perfect and—pchoom!—“ at which point we are given, in black and white, Kert, clad in a varsity letterman’s jacket, t-shirt, Levi’s rolled up at the cuff and white high top sneakers, a performance of the song likely as vibrant as any he gave on the stage—the kind of moment that makes you want to cue up the original Broadway cast album, in fact, and hear the whole glorious score.

(The amusing postscript to the West Side Story anecdote: the theatrical production was not a hit nor a critical favorite but the movie version was a “gigantic hit.” Bernstein took his name off the lyrics and gave the credit properly to Sondheim and said, “Of course we’ll adjust the royalties.” To which Sondheim replied: “Oh no, who cares about the money? It’s just the credit.” Pause, and Sondheim begins again: “If someone had only put a gag in my mouth at that point… But in fact we all thought the show was just going to be a prestigious show. Nobody dreamed it would be a hit, and in fact it wasn’t a hit. The show was disliked by most people. The score was disliked particularly in the papers and by the public. All of them said it couldn’t be hummed—it was all very exciting but they couldn’t hum anything.” After disc jockeys started playing the film soundtrack, everyone liked the songs—“they became hummable,” says a younger Sondheim, with undisguised scorn, “and that’s why the term ‘hummable’ drives me up a wall.”

Brief clip of the ‘Opening Doors’ segment of Six by Sondheim

Similar such priceless anecdotes dot the entire hour and a half: a terrific exposition by Sondheim on how Cole Porter worked, using the song “Just One of Those Things” as an example, with footage of the great Maurice Chevalier performing it in the 1960 film version of Can-Can; a wonderful restaging of the “Opening Doors” scene in Merrily We Roll Along (featuring Jeremy Jordan, Darren Criss and America Ferrar) to illustrate what Sondheim says is the only autobiographical song he’s ever written (“I was trying to capture what I was like when I was twenty-five and thirty years old. You try to write what you were like when you were twenty-five years old and you’re going to have a lot of trouble, and I did.”); and insight upon insight into the songwriter’s art, considered as process (“the songs I write don’t really reflect me in any conscious way. They all are about the characters the book writer has made, and I’m getting into those characters. I never think of it in my own terms at all.”); considered philosophically (“There’s that first moment of falling in love. Then you gotta let it cook and see if you’re still in love in the morning because it’s a form of showing off but it’s also a form of sharing when you say, ‘Hey, I caught a moment’ for people. And it’s a wonderful feeling. It’s what everyone who writes or paints or composes feels or else they wouldn’t go on with it. If you didn’t get those moments you couldn’t put up with the rest of it—the loneliness and the tedium and the endless amounts of work—the sweat.”); and considered humorously as “the sweat,” to wit: he says he always writes with a certain type of lead pencil that wears down fast because it allows him to “spend a lot of time sharpening, which is a lot more fun than sharpening,” and opines as to how alcohol is a useful writer’s tool “because it loosens up the inhibitions, as long as you don’t drink too much.”

Of course as Sondheim’s career has proceeded, as the years have rolled on, his writing has taken an increasingly reflective turn, epitomized by some of the most haunting songs in pop history, such as “Send In the Clowns” (from A Little Night Music) and “I Remember.” The whole of this journey is explored by focusing on the personal and professional mechanics, if you will, of six Sondheim songs (the abovementioned “Something’s Coming,” “Opening Doors” and “Send In the Clowns,” along with “I’m Still Here” [from Follies], “Being Alive” [from Company] and “Sunday” [from the transcendent Sunday in the Park with George]. It’s an arbitrary list of course, but each of the songs has special meaning for its composer. Given his portfolio of music and lyrics for more than 20 shows, fans of Sondheim’s art will doubtless grouse about this or that stunning tune not making the cut; and though the early sections on his childhood mentoring by Oscar Hammerstein II track the genesis of his calling (after his parents divorced, Sondheim’s mother, who lived near the Hammerstein family “kind of foisted me on them. They had a son about my age, Jimmy Hammerstein, and as a result I osmosed myself into the Hammerstein household and Dorothy and Oscar became surrogate parents during my teen years and that’s essentially how I became a songwriter, because I wanted to do what Oscar did.”), the absence of any mention of Robert Barrow, whom he studied with at Williams College, is curious, given that Barrow in many ways seems as key to Sondheim’s development as Hammerstein, if not more so. In a 2010 interview with Stephen Schiff for The Sondheim Review, Sondheim said he was almost alone in liking Barrow, whom “everyone hated because he was very dry, and I thought he was wonderful because he was very dry. Barrow made me realize that all my romantic views of art were nonsense. I had always thought an angel came down and sat on your shoulder and whispered in your ear ‘dah-dah-dah-DUM.’ Never occurred to me that art was something worked out. And suddenly it was skies opening up. As soon as you find out what a leading tone is, you think, Oh my God. What a diatonic scale is—Oh my God! The logic of it. And, of course, what that meant to me was: Well, I can do that. Because you just don’t know. You think it’s a talent, you think you’re born with this thing. What I’ve found out and what I believed is that everybody is talented. It’s just that some people get it developed and some don’t.”

Bernadette Peters leads a choral performance of ‘Sunday’ from Sunday in the Park with George, from the 1993 DVD release of Sondheim: A Celebration at Carnegie Hall

The reply to which might be, why don’t you take all this material available about Stephen Sondheim and whittle it down to an hour and a half? What’s here is choice and as expertly executed as it is inspired in concept. It’s hard to imagine anyone viewing Six by Sondheim not wanting to dig deeper into his work or to revisit it with a fresh perspective. This documentary emphasizes how much more there is to learn from his music—about ourselves.

Six by Sondheim airs on HBO on December 9, 9-10:30 (ET/PT); December 12 (9:30 a.m., 6:30 p.m.), December 15 (11:45 a.m.), December 17 (12:30 a.m.) and December 28 (2 p.m.).