During 1820 Keats displayed increasingly serious symptoms of tuberculosis, suffering two lung haemorrhages in the first few days of February. He lost large amounts of blood and was bled further by the attending physician. Leigh Hunt nursed him in London for much of the following summer. At the suggestion of his doctors, he agreed to move to Italy with his friend Joseph Severn, himself a portrait and subject artist. On 13 September, they left for Gravesend and four days later boarded the sailing brig “Maria Crowther,” where he made the final revisions of “Bright Star.” The journey was a minor catastrophe: storms broke out followed by a dead calm that slowed the ship’s progress. When they finally docked in Naples, the ship was held in quarantine for ten days due to a suspected outbreak of cholera in Britain. Keats reached Rome on 14 November, by which time any hope of the warmer climate he sought had disappeared.

Over the course of Keats’s three-month dying ordeal, Severn kept the Keats circle in England informed of the poet’s deteriorating condition, with William Haslam and Charles Armitage Brown being the most favored recipients of such correspondence. Following Severn’s own passing on 3 August 1879, his papers–letters, journals, reminiscences and fragmentary records–were turned over, as Severn had requested, to his editor, William Sharp. The original plan was to publish this mass of material in two volumes, the first concentrating on, as its title would have indicated, Keats and His Circle, the second focused on Severn’s life from 1840 on to his final years in Rome (1871-79). Instead, it was decided to consolidate and abridge the material into a single volume, “a more concise record,” as Sharp explained. Recent Severn biographers have found some meaningful material in the expunged documents but nothing has surfaced to alter the drama and sorrow (and even some bouts of self-pity) Severn described in his letters as Keats slowly succumbed to the dreaded disease that had devastated his family, claiming his mother and his brother Tom before him. These wrenching missives include such unbearably poignant scenes as Keats being unable to read a final letter from his beloved Fanny Brawne and requesting Severn place it over his heart, and bury it with him; and, in writing to Brown with news of Keats’s passing, trying to describe the poet’s final moments but finally breaking down, unable to complete his last thought, and so concluding instead with a drawing of a mourning figure, a truly heartbreaking image.

In The Life and Letters of Joseph Severn (Samson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1892), Sharp describes, with the help of Severn’s letters, the final days of John Keats as told by the only person attending the doomed poet as he breathed his last. Sharp’s voice is heard first; Severn’s is indicated in either quotation marks or italics.

Throughout the long and trying period of Severn’s unflagging ministry to his dying friend he had been fertile in expedients, in trivial matters as well as in pecuniary troubles. He has himself told us how, overcome with fatigue, he would sometimes fall asleep in the night-watches, and, awakening, find himself enveloped in total darkness.

“To remedy this, one night I tried the experiment of fixing a thread from the bottom of a lighted candle to the wick of an unlighted one, that the flame might be conducted, all of which I did without telling Keats. When he awoke and found the first candle nearly cut, he was reluctant to wake me, and while doubting, suddenly cried out, ‘Severn! Severn! Here’s a little fairy lamplighter actually lit up the other candle.’”

Certainly no one had a more loyal friend and tender nurse than Keats had in Severn. There is a touch of deep pathos in the latter’s simple yet eloquent words: —

“Poor Keats has me ever by him, and shadows out the form of one solitary friend; he opens his eyes in great doubt and horror, but when they fall upon me they close gently, open quietly and close again, till he sinks to sleep.”

This passage occurs in one of the most pathetic of all Severn’s letters to his friends. It was addressed to Haslam and written the day before Keats’s death.

Feb. 22

“My Dear Haslam–

O, how anxious I am to hear from you! I have nothing to break this dreadful solitude but letters. Day after day, night after night, here I am by our poor dying friend. My spirits, my intellect, and my health are breaking down. I can get no one to change with me–no one to relieve me. All run away, and even if they did not, Keats would not do without me. Last night I thought he was going, I could hear the phlegm in his throat; he bade me lift him up on the bed or he would die with pain. I watched him all night, expecting him to be suffocated at every cough. This morning, by the pale daylight, the change in him frightened me; he has sunk in the last three days to a most ghastly look. Though Dr. Clark has prepared me for the worst, I shall be ill able to bear to be set free even from this, my horrible situation, by the loss of him. I am still quite precluded from painting, which may be of consequence to me. Poor Keats has me ever by him, and shadows out the form of one solitary friend; he opens his eyes in great doubt and horror, but when they fall upon me they close gently, open quietly and close again, till he sinks to sleep. This thought alone would keep me by him till he dies; and why did I say I was losing my time? The advantages I have gained by knowing John Keats are double and treble any I could have won by any other occupation. Farewell.

“At times during his last days he made me go to see the place where he was to be buried, and he expressed pleasure at any description of the locality of the Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, about the grass and the many flowers, particularly the innumerable violets, also about a flock of goats and sheep and a young shepherd–all these intensely interested him. Violets were his favourite flowers, and he joyed to hear how they overspread the graves. He assured me ‘that he already seemed to feel the flowers growing over him.’

“During the last few days he became very calm and resigned. Again and again, while warning me that his death was fast approaching, he besought me to take all care of myself, telling me that ‘I must not look at him in his dying gasp nor breathe his passing breath, not even breathe upon him.’ From time to time he gave me all his directions as to what he wanted done after his death. It was in the same sad hour when he told me with greater agitation than he had shown on any other subject, to put the letter which had just come from Miss Brawne (which he was unable to bring himself to read, or even to open), with any other that should arrive too late to reach him in life, inside his winding-sheet on his heart–it was then, also, that he asked that I should see cut upon his gravestone as sole inscription, not his name, but simply, ‘Here lies one whose name was writ in water.’”

ohn Keats in his Last Illness, a sketch by Joseph Severn. At the bottom, in Severn’s hand, is the artist’s signature, and the date and time: 28 Jan 1821, 3 O’clock morn. This sketch was published in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, May to October, 1883

John Keats in his Last Illness, a sketch by Joseph Severn. At the bottom, in Severn’s hand, is the artist’s signature, and the date and time: 28 Jan 1821, 3 O’clock morn. This sketch was published in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, May to October, 1883

Throughout Keats’s latter days Severn was much cheered by the sympathy and constant attention of Dr. and Mrs. Clark, and of Mr. William Ewing, an English sculptor, who had a profound interest in the dying poet, and was eager to be of any service to him, or his devoted friend. But at last the inevitable moment came.

“He remained quiet to the end, which made the death-summons more terrible. It happened about half-past four on the afternoon of Friday, the 23rd. He held my hand to the last, and he looked up at me until his eyes lost their speculation and dimmed in death. I could hear the phlegm boiling and tearing his chest. He gasped to me to lift him up, and in a short time died in my arms without effort, and even with deadly rejoicing that it had come at last, that for which he had so ardently longed for months. And I confess that his pallid dead face was for awhile to me a consolation, for I had seen it express such suffering. I had seen it waste away in that suffering, and I had seen that suffering long and in loneliness, and it was a happiness to think that the poor fellow’s misery was over.”

And so the long tragic episode comes to a close, and with the relaxation of the severe strain Severn gave way completely. Even four or five days later, he could not at first sufficiently control his grief to finish a letter he began, intended for Brown. The fragment remains among his papers.

“My dear Brown,” it begins and then goes on without further preamble, “He is gone. He died with the most perfect ease. He seemed to go to sleep. On the 23rd, Friday, at half-past four, the approach of death came on. ‘Severn–I–lift me up, for I am dying. I shall die easy. Don’t be frightened! Thank God it has come.’ I lifted him up in my arms, and the phlegm seemed boiling in his throat. This increased until eleven at night, when he gradually sank into death, so quiet, that I still thought he slept–but I cannot say more now. I am broken down beyond my strength. I cannot be left alone. I have not slept for nine days, I will say the day since— On Saturday a gentleman came to cast the face, hand, and foot. On Sunday his body was opened; the lungs were completely gone, the doctors could not conceive how had lived in the last two months. Dr. Clark will write you on this head. …..”;

The letter is scrawled, and as though written by a tremulous hand. It breaks off just over the second page, and on the third is a roughly drawn but suggestive figure of one mourning.

It is not surprising that, with all his fortitude and philosophical way of looking always at the best side of things, Severn was utterly prostrated. He was, truly enough, glad to see the calm of death upon the features he had so often beheld distraught by bodily and mental agony; and yet the final loss of so dear a friend was a bitter grief: “one so dear that up to his death I know not how to trace its value, one so fascinating, not only in the power of his genius, but also in the charm of his manners, and one I had known so long in the constant and sincere communion of our two arts of Poetry and Painting–this great loss, the loss of all these, came upon me, and I sank under the blow most painfully; with difficulty, and only, indeed, by a great effort, recovering sufficiently to be present at the funeral.”

John Keats was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome. Joseph Severn died on August 3, 1879 at the age of 85. He too was buried in Rome’s Protestant Cemetery, alongside John Keats.

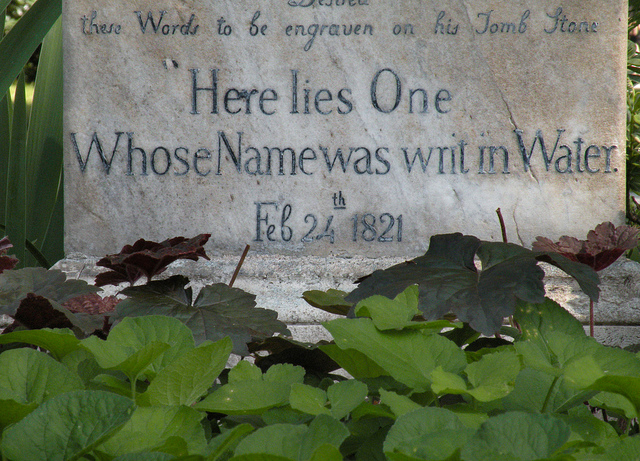

Keats’s epitaph reads:

This Grave

contains all that was mortal

of

YOUNG ENGLISH POET

Who

on his Death Bed

in the Bitterness of his Heart

at the Malicious Power of his Enemies

Desired

these words to be engraved on his Tomb Sonte

Here lies One

whose name was writ in Water

Feb 24th 1821

Sources: Wikipedia; The Life and Letters of Joseph Severn by William Sharp (Samson Low, Marston & Company, London, 1892)