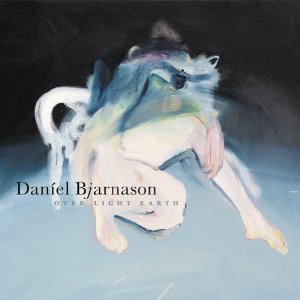

OVER LIGHT EARTH

Daniel Bjarnason

Bedroom Community

Daníel Bjarnason’s debut album, Processions, came out in 2009 amidst global economic and political meltdown. It was physical and driven, often desperate and angry–the unforgettable climactic rhythm of the “Red-Handed” movement from “Processions,” for example, or the way the “Bow to String” concerto, with its images of blood and bone and breath, spoke of a painfully human struggle, multitracked cello forming a multitude of crying throats. The album was the explosive sound of its times, some of the effects of which were felt particularly painfully in Bjarnason’s native Iceland. Processions was all boiling vitriol and anxious disharmony.

Four years on, the picture is different, and so is Over Light Earth. Overall, it is a quieter album (of course, Processions had its quiet sections and Over Light Earth has its loud ones, but generally speaking). This mirrors the current climate; the shouting and the rage are, for the western world, largely over. It seethes rather than boils. The three movements of “Emergence,” the middle piece of the album, follow an imagined trajectory of soft discomfort steadily evolving into dissent. The first movement, appropriately titled “Silence,” is quieter than almost anything from Processions, long string notes sliding restlessly over each other, steadily growing louder and punctured by high squeals of violin–think Greg Haines scoring a European ghost film. It’s scarier than anything Bjarnason has done before, filled with the measured fury of a people who have had time to let their discontent really settle in. The second movement, “Black Breathing,” amplifies the restlessness, deploying a recurring motif throughout this school of contemporary orchestral music of harsh, staccato bursts flickering throughout the orchestra alongside Bjarnason’s trademark low, tremolo rumbles. This ceaselessly moving anxiety coalesces in the final movement, “Emergence,” into one of the most harmonious passages of the album. It is no less urgent, with its sweeping dynamics and surge to the conclusion, but the whole orchestra seems to be working as one huge, chord-producing entity. As it draws to the climax you realize that this is the sum of the harmonic clashes of the previous movements, each fitful burst and hidden melody brought into a broad, purposeful whole.

The piece imagines a narrative of insular anger and internal conflict resolved into an inclusive, united movement. In this reading the very term “movement” becomes loaded, making another link between the pieces of music and the actions of people as political beings. Our time could do with a similar narrative–resolving personal troubles and living room debates into a meaningful (inter)national question. If the crises of recent years pass without change, it’s unlikely to be because people didn’t want it, but because we didn’t have the will to go out and find other people with the same troubles, the same desires, and do something.

AUDIO CLIP: Daniel Bjarnason, ‘Solitudes I, Holy,’ from Over Light Earth

The contemporary concerns of Over Light Earth are also contained in its modern recording techniques. The close miking used on the orchestra make for an intimate sound not usually associated with ensembles this large. You can hear individual violins in the strings, like a personal testimony cutting through the abstraction of the 6 o’clock news. Bjarnason’s humanizing of the orchestra is his most contemporary innovation. He opposes the faceless ‘classics’ trotted out in concert halls the world over, rejects an impersonal, elitist narrative of orchestral music (one that may well have died out compositionally speaking decades ago but still dominates popular consciousness. Ask someone about classical music and they’ll likely give you Mozart before Stravinsky and Stravinsky before Gavin Bryars). This attitude to the canon complements the album’s relationship with contemporary politics, dissident and firmly rooted in universal, everyday experience. But this doesn’t mean the music is individualist or anarchist; it’s more of a middle way. It’s still an orchestra after all, a single body, whose composer/orchestrator/leader is very much a part of it (Bjarnason himself conducts and plays piano and synths), working in unison, engaged with its constituent parts. It is a non-revolutionary ideal of a societal structure, embodied in music.

“Solitudes,” a piano concerto that actually predates Processions but seems much more suited to this album, demonstrates this outlook best. The piece rumbles with the same kind of compressed energy as “Emergence,” opening with delicate, isolated instruments twisting around each other’s notes until the cello brings in some weight and searching string chords. Even the prepared piano seems coiled tightly about itself, its natural sound ready to spring forth when it enters in the second movement. A concerto might seem an odd vehicle to explore Bjarnason’s ideas of unity and equality, since they traditionally operate around one leading instrument, but it actually works pretty perfectly. The piano may be central, but it is hardly dominant. It relies on the strings to bring most of the drama (the thunder claps of “Dance Around in Your Bones”), woodwind for many of the flitting, dancing effects, Valgeir Sigurðsson and Ben Frost’s impossibly subtle electronics to fill in atmospheric gaps, and in the most heavily prepared sections it barely sounds like a piano at all, despite generally being more melodically prepared than might be expected. The recording technique only enhances all these collective qualities; there’s really no way the piece could survive without the piano or its accompaniments.

AUDIO CLIP: Daniel Bjarnason, ‘Solitudes II. Dance Around In Your Bones,’ from Over Light Earth

The title piece–and arguably the album’s centerpiece, although it comes first– is a 15-minute composition in two movements taking its inspiration from the New York School of painters from the mid-20th Century; the movements take their names from works by Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, respectively. Bjarnason’s music shares several characteristics with these abstract expressionists. The piece is physical (again, accentuated by the recording technique), bringing to mind Pollock’s famous style of painting, stalking around a canvas dripping and flinging paint across it–the music is mobile, sometimes threatening, the individualized instruments cast like lines of color, sometimes apparently randomly but adding up to a greater whole. You can’t look at a Pollock and think most significance lies in any particular line, although each is intricate and vital. Similarly with Over Light Earth, its power comes from accumulation and co-operation rather than singular flourishes. The link with Rothko is harder to see, given the painter’s vast blocks of color and the often fragmentary, stuttering nature of the composer’s music. But the real joy in a Rothko comes from the close-up detail, the subtly blended textures, tiny ridges of paint and drifts of shade within the canvas’ main divisions. Bjarnason benefits from the same close attention, revealing brief tonal discords within sections of the orchestra, an unformed melody or a struggling harmony amongst the unsettled dissonance (or vice versa in the harmonious passages).

Perhaps the most telling comparison, however, is the way in which both the abstract expressionists and Bjarnason take the old and the new, and move forward. Pollock, for example, was influenced by the size and scope of Monet’s Water Lilies and by German expressionism of the early 20th Century, but his art resembles nothing more than a Jackson Pollock. Over Light Earth contains much of the pre-existing traditions of classical music, but also much of modern music. In many ways, the 21st Century composer’s life isn’t so different to the 18th or 19th Centuries–commissions, concertos, many or most of the instruments used are virtually unchanged–and this may well be why so many parts of the classical music world are so stagnant. But Bjarnason brings new techniques to these old forms; he brings new production methods, the influence of electronic music, of atonality (though that is hardly new) and his own sonic flavor. He gathers all these up and remakes them into something personal and new, in the same way that Max Richter’s Vivaldi Recomposed did last year, although Richter’s melding was perhaps a little more complete. In the end, Over Light Earth resembles nothing more than a Daníel Bjarnason album.

AUDIO CLIP: Daniel Bjarnason, ‘Emergence 1. Silence,’ from Over Light Earth

It’s not a perfect album. It’s not as immediately captivating as Processions was, often the movements are too short to gather that album’s cumulative, rolling power and Bjarnason is too fond of ending pieces with a long, loud, thoroughly conclusive chord. But it is another important step towards solidifying the composer’s already pretty well defined identity and towards building a movement of contemporary orchestral and chamber music that is aware of, but not beholden to, tradition, that crosses over into and from other genres of modern music and is engaged with the musical and political movements of its times.

Review from Fluid Radio. Support Fluid Radio, which relies entirely on listener donations to continue its mission “to support and promote new as well as established artists/labels in the field of experimental music.” Click here to make a donation.