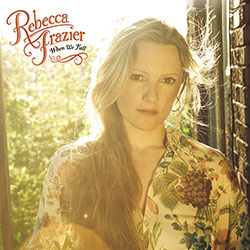

Rebecca Frazier in repose: ‘In my heart you’ll be running wild, running free/Dancing once more here with me.’

WHEN WE FALL

Rebecca Frazier

Amtoco Records

On first glance the washed-out shot of Rebecca Frazier on the cover of her new album When We Fall seems like a mistake, all faded autumnal colors complementing the artist’s dour, faraway expression. Study it closer, however, and its severity softens when you notice the halo effect around Frazier’s head and how she seems not a static, sorrowful figure but rather someone walking into light, almost out of another dimension, in fact, and the eyes that first impressed as being weepy now appear set, as do her thin lips, in a determined, steely gaze radiating strength.

So it is that When We Fall, born in tragedy, becomes a stirring, at times high-spirited, celebration of life, love and spiritual reconciliation. In November 2010 her youngest of two sons, Charlie, died; her response to this unspeakable tragedy, the worst a parent can endure, was to turn to her art: “I knew I could rely on creativity and hope in order to heal,” she writes in her brief liner notes. A chance meeting with producer Brent Truitt (whose resume includes work with the Dixie Chicks and Alison Krauss) gave rise to their discussing an album project. Frazier and her husband and musical collaborator John continued writing and, well, doing other things. Soon there was a batch of new original songs, then the onset of sessions for the new album, and finally, a new addition to the Frazier family, a daughter, Cora. That When We Fall, despite its sober title, is infused with so much life, honors the Fraziers’ resilience, their new daughter and the spirit of their departed son.

Rebecca Frazier and Hit & Run Bluegrass at the Station Inn, Nashville, June 14, performing the title track from When We Fall

If a listener knows this history–all you have to do is read the liner notes to learn of it–a natural tendency would be to expect the songs to reflect on the cataclysmic event of 2010 and the blessed one following in its wake. Do that, and you might miss the many pleasures When We Fall has to offer. Frazier is in superb voice throughout, conjuring the ethereal otherness of Alison Krauss in the softer, reflective passages, but attacking the uptempo parts with bracing vigor, singing exultantly in that bold, ringing mountain tone so reminiscent of Rhonda Vincent. Supporting her efforts are, in addition to hubby John on mandolin and harmony vocals, an all-star lineup featuring Ron Block (banjo) and Barry Bales (acoustic bass), whose primary employer is one Alison Krauss; Andy Hall on dobro, recruited from the Infamous Stringdusters; bluegrass stalwart Scott Vestal (whose long career includes tenures with Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver, Sam Bush, John Cowan, Continental Divide, Johnny Staats, Larry Sparks and others as he also cultivates a solo career); fiddle virtuoso Shad Cobb, who’s popped up on recordings ranging from the Osborne Brothers to Shenandoah to Willie Nelson to Steve Earle, et al.; and harmony vocalist Shelby Means, who is otherwise the bassist for the all-female roots phenoms Della Mae. Together they make some mighty powerful music.

But if we’re talking about gifted musicians we might as well start with Rebecca Frazier herself. One of the most celebrated flatpickers to emerge in recent years–she gets the highest praise from the likes of Bryan Sutton–Frazier steps out at select moments here (notably on three of her self-penned instrumentals), at which points the album’s wow factor increases about tenfold. The first exhilarating taste of what she can do comes four songs in, on her original instrumental “Virginia Coastline,” a rousing bluegrass toe-tapper she kicks off with a few bars of precision speed picking that veers ever so slightly into blues before it gives way to a high stepping, driving fiddle solo from Cobb, who yields the floor to an exuberant Vestal ahead of all three players converging in celebratory fashion midway through. She and Cobb face off again in another Frazier original, the sprint titled “Clifftop,” in which Vestal’s banjo eagerly joins the fray in a workout that has the feel of a sea chanty on steroids. More moody and atmospheric, another instrumental, “40 Blues,” teases at the outset with Frazier’s searching, tentative probings, then begins to congeal when Hall adds dobro flourishes before it breaks into a galloping, dobro-fueled pace.

From her new album When We Fall, Rebecca Frazier’s ‘Darken Your Doorway’

No matter these instrumental pyrotechnics, this day belongs to Frazier’s emotional singing and the strong songs she wrote on her own and with husband John. She makes more of Neil Young’s “Human Highway” than the song probably deserves and in fact remakes it into a kind of personal howl against humankind’s indifference to suffering, complete with a soaring, pealing chorus, with tasty solos from John Frazier (mandolin) and Ron Block (banjo) along the way. The old-timey “Better Than Staying” sounds like it might have come out of the Civil War era but in fact it’s the Fraziers’ perspective on not settling for the hand you’ve been dealt when you can exercise other, more fruitful options. Interestingly, the title track, written by Frazier alone, seems to counter the philosophy advanced in “Better Than Staying.” A reflective mid-tempo bluegrass ballad, it limns a woman’s contentment with the status quo. In her singsong reading, she hints she’s seen enough of an alternative lifestyle to know its downside isn’t worth it via an allusion to Original Sin that raises a whole bunch of other questions: “Reaching ripe fruit growing on the tree/Eyes getting wide ‘cause I can see/All the bad that comes with the good/All the pain I never understood…”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BQThay6bJ2s

A powerful live performance of Neil Young’s ‘Human Highway,’ the first cut on When We Fall. Video from a performance at The Pour House in Charleston, SC.

“Morning & Night,” an uptempo bluegrass love song, could easily be the sequel to “When We Fall” in its revelations of how a fulfilling relationship has given her a new perspective on the delusion of happiness she had in her single years. Singing sweet and warm, with the slightest of keening phrases and rich harmony support from Shelby Means, over the steady pulse provided by banjo, fiddle, mandolin and bass with sprinklings of solos (including her own to-the-point guitar) punctuating the soundscape, Frazier asserts thoughtfully, “When I flew solo long ago/I kept thinking that I was free/Now I no longer go alone/And I feel freer than I ever thought I’d be…” On the other hand, when love comes a-cropper, it’s rough: “Love, Go Away from This House” is a bluesy bluegrass kissoff that makes good use of the emotive qualities of Hall’s dobro as Frazier minces no words about the destructive effects of her man’s faithlessness, likening herself to “a dead branch behind a dark black sky” and signing off with a scorching “You did your work and you did it good.” The saga continues in “Darken Your Doorway,” which treads dangerously close to self pity but never loses its backbone as the singer describes the telltale signs of an imploding relationship and finally exits with an assertive “No need to get up from your chair, dear/I can let myself out just fine…” Ron Block shines with a teary banjo solo here, but Frazier’s measured reading of her note-perfect litany of grievances makes the song greater than the sum of its parts (and a perfect Rhonda Vincent cover to boot).

AUDIO CLIP: from Rebecca Frazier’s When We Fall, ‘Babe in Arms’

The reference at the outset of this review to “spiritual reconciliation” refers directly to the final, magnificent song, written by Rebecca and John, “Babe in Arms,” the album’s one explicit reference to the child the couple lost in 2010. Understated and hymn-like, with John’s mandolin chops and Cobb’s soft, weeping fiddle the dominant instrumental voices, Frazier sings in a clear but wounded voice of the family’s loss and of fitful efforts at making peace with the absence of a loved one she thought she would spend her life with. In a concise 3:12 she fairly works through the stages of grief and comes out, in the final verse, not merely accepting the loss but arriving at a place where she celebrates the life instead of mourning the death: “You were mine for a night/Held you close, held you tight/In my heart you’ll be running wild, running free/Dancing once more here with me.”

At which point we are back where we began, with Rebecca Frazier not fading out but being bathed in light, bright light, and whole again. As much as it is a musical achievement, When We Fall persists in memory for its flesh and blood humanity. Rebecca Frazier will be heard from by dint of her artistry as a singer, songwriter and instrumentalist but the heart informing her music makes all the difference. It also explains the weird light bathing her on the cover–it’s Heaven-sent.