Caruso’s caricature of himself as Federico Loewe in Franchetti’s Germania

(Ed. note: In 1909 Metropolitan Publishers in New York published The Art of Singing, with the credited authors being the two foremost Italian singers of the day–and of all time–Luisa Tetrazzini and Enrico Caruso. Not a book the two premier vocalists wrote but rather purportedly verbatim transcripts of their public utterances, lectures and such on their art form, “what to do” and “what not to do,” as the preface below states, principally aimed at aspiring singers. An excerpt from Caruso follows.)

IN OFFERING this work to the public the publishers wish to lay before those who sing or who are about to study singing, the simple, fundamental rules of the art based on common sense. The two greatest living exponents of the art of singing—Luisa Tetrazzini and Enrico Caruso—have been chosen as examples, and their talks on singing have additional weight from the fact that what they have to say has been printed exactly as it was uttered, the truths they expound are driven home forcefully, and what they relate so simply is backed by years of experience and emphasized by the results they have achieved as the two greatest artists in the world.

Much has been said about the Italian Method of Singing. It is a question whether anyone really knows what the phrase means. After all, if there be a right way to sing, then all other ways must be wrong. Books have been written on breathing, tone production and what singers should eat and wear, etc., etc., all tending to make the singer self-conscious and to sing with the brain rather than with the heart. To quote Mme. Tetrazzini: “You can train the voice, you can take a raw material and make it a finished production; not so with the heart.”

The country is overrun with inferior teachers of singing; men and women who have failed to get before the public, 6 turn to teaching without any practical experience, and, armed only with a few methods, teach these alike to all pupils, ruining many good voices. Should these pupils change teachers, even for the better, then begins the weary undoing of the false method, often with no better result.

To these unfortunate pupils this book is of inestimable value. He or she could not consistently choose such teachers after reading its pages. Again the simple rules laid down and tersely and interestingly set forth not only carry conviction with them, but tear away the veil of mystery that so often is thrown about the divine art.

Luisa Tetrazzini and Enrico Caruso show what not to do, as well as what to do, and bring the pupil back to first principles—the art of singing naturally.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMXScCik6Jo

In her only appearance on film, Luisa Tetrazzini sings along with a recording by her late friend Enrico Caruso (1932 Movietone Newsreel)

From a Personal Viewpoint

By Enrico Caruso

Of the thousands of people who visit the opera during the season few outside of the small proportion of the initiated realize how much the performance of the singer whom they see and hear on the stage is dependent on previous rehearsal, constant practice and watchfulness over the physical conditions that preserve that most precious of our assets, the voice.

Nor does this same great public in general know of what the singer often suffers in the way of nervousness or stage fright before appearing in front of the footlights, nor that his life, outwardly so fêted and brilliant, is in private more or less of a retired, ascetic one and that his social pleasures must be strictly limited.

These conditions, of course, vary greatly with the individual singer, but I will try to tell in the following articles, as exemplified in my own case, what a great responsibility a voice is when one considers that it is the great God-given treasure which brings us our fame and fortune.

Enrico Caruso, ‘O Holy Night’

I am perhaps more favored than many in the fact that my voice was always “there,” and that, with proper cultivation, of course, I have not had to overstrain it in the attempt to reach vocal heights which have come to some only after severe and long-continued effort. But, on the other hand, the finer the natural voice the more sedulous the care required to preserve it in its pristine freshness to bloom. This is the singer’s ever present problem-in my case, however, mostly a matter of common sense living.

As regards eating-a rather important item, by the way-I have kept to the light “continental” breakfast, which I do not take too early; then a rather substantial luncheon toward two o’clock. My native macaroni, specially prepared by my chef, who is engaged particularly for his ability in this way, is often a feature in this midday meal. I incline toward the simpler and more nourishing food, though my tastes are broad in the matter, but lay particular stress on the excellence of the cooking, for one cannot afford to risk one’s health on indifferently cooked food, no matter what its quality.

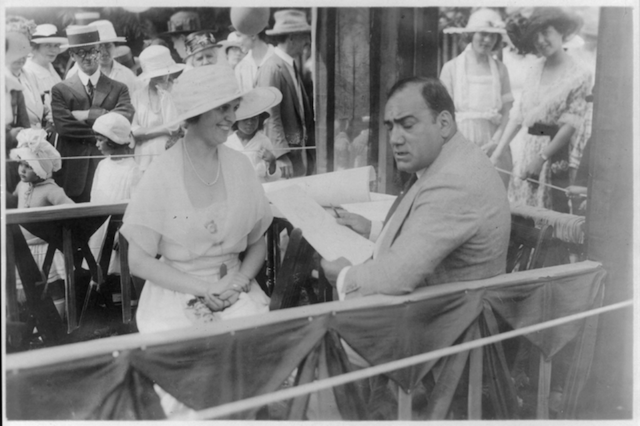

Caruso drawing caricature sketches in booth at a charity fair in Southampton, L.I., with Mrs. Albert Gallatin, August 3, 1920. Almost a year later to the day, on August 2, 1921, he died in Italy.

On the nights when I sing I take nothing after luncheon, except perhaps a sandwich and a glass of Chianti, until after the performance, when I have a supper of whatever I fancy within reasonable bounds. Being blessed with a good digestion, I have not been obliged to take the extraordinary precautions about what I eat that some singers do. Still, I am careful never to indulge to excess in the pleasures of the table, for the condition of our alimentary apparatus and that of the vocal chords are very closely related, and the unhealthy state of the one immediately reacts on the other.

My reason for abstaining from food for so long before singing may be inquired. It is simply that when the large space required by the diaphragm in expanding to take in breath is partly occupied by one’s dinner the result is that one cannot take as deep a breath as one would like and consequently the tone suffers and the all-important ease of breathing is interfered with. In addition a certain amount of bodily energy is used in the process of digestion which would otherwise be entirely given to the production of the voice.

Enrico Caruso, ‘Santa Lucia,’ recorded March 20, 1916, heard here in a digitally remastered version. The Neapolitan lyrics of ‘Santa Lucia’ celebrate the picturesque waterfront district, Borgo Santa Lucia, in the Bay of Naples, in the invitation of a boatman to take a turn in his boat, the better to enjoy the cool of the evening. (Tom Frøkjær, YouTube)

These facts, seemingly so simple, are very vital ones to a singer, particularly on an “opening night.” A singer’s life is such an active one, with rehearsals and performances, that not much opportunity is given for “exercise,” and the time given to this must, of course, be governed by individual needs. I find a few simple physical exercises in the morning after rising, somewhat similar to those practiced in the army, or the use for a few minutes of a pair of light dumbbells, very beneficial. Otherwise I must content myself with an occasional automobile ride. One must not forget, however, that the exercise of singing, with its constant deep inhalation (and acting in itself is considerable exercise also), tends much to keep one from acquiring an over-supply of embonpoint.

A proper moderation in eating, however, as I have already said, will contribute as much to the maintenance of correct proportion in one’s figure as any amount of voluntary exercise which one only goes through with on principle.

As so many of you in a number of States of this great country are feeling and expressing as well as voting opinions on the subject of whether one should or should not drink intoxicants, you may inquire what practice is most in consonance with a singer’s well being, in my opinion. Here, again, of course, customs vary with the individual. In Italy we habitually drink the light wines of the country with our meals and surely are never the worse for it. I have retained my fondness for my native Chianti, which I have even made on my own Italian estate, but believe and carry out the belief that moderation is the only possible course. I am inclined to condemn the use of spirits, whisky in particular, which is so prevalent in the Anglo-Saxon countries, for it is sure to inflame the delicate little ribbons of tissue which produce the singing tone and then–addio to a clear and ringing high C!

Early Caruso, 1904 (he began his recording career in 1902), Una Furtiva Lagrima (A furtive tear), the romanza from Act II, Scene 2 of the Italian opera, L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love) by Gaetano Donizetti. It is sung by Nemorino (Caruso) when he finds that the love potion he bought to win his dream lady’s heart, Adina, works. Recorded February 1, 1904, in Room 826, Carnegia Hall, New York, NY. (Tom Frøkjær, YouTube)

Early Caruso, 1910, Ora e per sempre addio from Act 2 of Verdi’s Otello

Though I indulge occasionally in a cigarette, I advise all singers, particularly young singers, against this practice, which can certainly not fail to have a bad effect on the delicate lining of the throat, the vocal chords and the lungs.

You will see by all the foregoing that even the gift of a good breath is not to be abused or treated lightly, and that the “goose with the golden egg” must be most carefully nurtured.

Outside of this, however, one of the great temptations that beset any singer of considerable fame is the many social demands that crowd upon him, usually unsought and largely undesired. Many of the invitations to receptions, teas and dinners are from comparative strangers and cannot be considered, but of those from one’s friends which it would be a pleasure to attend very few indeed can be accepted, for the singer’s first care, even if a selfish one, must be for his health and consequently his voice, and the attraction of social intercourse must, alas, be largely foregone.

The continual effort of loud talking in a throng would be extremely bad for the sensitive musical instrument that the vocalist carries in his throat, and the various beverages offered at one of your afternoon teas it would be too difficult to refuse. So I confine myself to an occasional quiet dinner with a few friends on an off night at the opera or any evening at the play, where I can at least be silent during the progress of the acts.

More early Caruso, 1907, La Donna e Mobile, from Verdi’s Rigoletto

In common with most of the foreign singers who come to America, I have suffered somewhat from the effects of your barbarous climate, with its sudden changes of temperature, but perhaps have become more accustomed to it in the years of my operatic work here. What has affected me most, however, is the overheating of the houses and hotels with that dry steam heat which is so trying to the throat. Even when I took a house for the season I had difficulty in keeping the air moist. Now, however, in the very modern and excellent hotel where I am quartered they have a new system of ventilation by which the air is automatically rendered pure and the heat controlled-a great blessing to the over-sensitive vocalist.

After reading the above the casual person will perhaps believe that a singer’s life is really not a bit of a sinecure, even when he has attained the measure of this world’s approval and applause afforded by the “great horseshoe.”

Following this introductory essay Caruso went on to address specific issues related to vocal performance: “The Voice and Tone Production,” “Faults to be Corrected,” “Good Diction a Requisite” and the last, reprinted below, “Pet Superstitions of Great Singers.”

Pet Superstitions of Great Singers

On May 28, 1921, an ailing Caruso sailed for Italy with wife Dorothy and daughter Gloria aboard the S.S. Presidente Wilson. He died in Naples on August 3, 1921. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

The most visible phase of the opera singer’s life when he or she is in view of the public on the stage is naturally the one most intimately connected in the minds of the majority of people with the singer’s personality, and yet there are many happenings, amusing or tragic, from the artist’s point of view, which, though often seen, are as often not realized in their true significance by the audience in front of the orchestra. One might naturally think that a singer who has been appearing for years on the operatic stage in many lands would have overcome or outgrown that bane of all public performers, stage fright. Yet such is far from the case, for it seems as though the greater the artistic temperament the more truly the artist feels and the more of himself he puts into the music he sings the greater his nervousness beforehand. The latter is of course augmented if the performance is a first night and the opera has as yet been untried before a larger public.

This advance state of miserable physical tension is the portion of all great singers alike, though in somewhat varying degrees, and it is interesting to note the forms it assumes with different people. In many it is shown by excessive irritability and the disposal to pick quarrels with anyone who comes in contact with them. This is an unhappy time for the luckless “dressers,” wig man and stage hands, or even fellow artists who encounter such singers before their first appearance in the evening. Trouble is the portion of all such.

In other artists the state of mind is indicated by a stern set countenance and a ghastly pallor, while still others become slightly hysterical, laugh uproariously at nothing or burst into weeping. I have seen a big six-foot bass singer, very popular at the opera two or three seasons ago, walking to and fro with the tears running down his cheeks for a long time before his entrance, and one of our greatest coloratura prima donnas has come to me before the opera, sung a quavering note in a voice full of emotion and said, with touching accents: “See, that is the best I can do. How can I go on so?”

Caruso, Campane a sera (Evening Bells) by Vincenzo Billi; recorded September 26, 1918

I myself have been affected often by such fright, though not always in the extreme degree above described. This nervousness, however, frequently shows itself in one’s performance in the guise of indifferent acting, singing off the key, etc. Artists are generally blamed for such shortcomings, apparent in the early part of the production, when, as a matter of fact, they themselves are hardly conscious of them and overcome them in the course of the evening. Yet the public, even critics, usually forget this fact and condemn an entire performance for faults which are due at the beginning to sheer nervousness.

The oft-uttered complaint that operatic singers are the most difficult to get on with of any folk, while justified, perhaps, can certainly be explained by the foregoing observations.

We of the opera are often inclined to be superstitious in a way that might annul matter of fact Americans. One woman, a distinguished and most intelligent artist, crosses herself repeatedly before taking her “cue,” and a prima donna who is a favorite on two continents and who is always escorted to the theatre by her mother, invariably goes through the very solemn ceremony of kissing her mother good-by and receiving her blessing before going on to sing. The young woman feels that she could not possibly sing a note if the mother’s eye were not on her every moment from the wings.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQPgYCoEd8I

Caruso, Tarantella Sincera, a Neapolitan song composed by Vincenzo de Crescenzo, recorded December 27, 1911

Another famous singer wears a small bracelet that was given to her when an infant by Gounod. She has grown somewhat stout of late years, and the hoop of gold has been reënforced so often that there is hardly any of the great composer’s original gift left. Still, she feels that it is a charm which has made her success, and whether she sings the part of a lowly peasant or of a princess the bracelet is always visible.

And these little customs are not confined to the woman singers either, for the men are equally fond of observing some little tradition to cheer them in their performance. These little traits, trivial perhaps in themselves, are of vital importance in that they create a sense of security in the soul of the artist, who goes on his way, if not rejoicing, at least convinced that the fates are not against him.

One of the penalties paid by the singers who are much in the public eye is the constant demand made on them to listen to voices of vocal aspirants-not always very young ones, strange to say. It is sad to contemplate the number of people who think they can sing and are destined by talent and temperament for operatic careers, who have been led by misguided or foolish friends and too often by overambitious and mercenary singing masters into spending time and money on their voices in the fond hope of some day astonishing the world. Alas, they do not realize that the great singers who are heard in the New York opera houses have been picked from the world’s supply after a process of most drastic selection, and that it is only the most rarely exceptional voice and talent which after long years of study and preparation become worthy to join the elect.

I am asked to hear many who have voices with promise of beauty, but who have obviously not the intelligence necessary to take up a career, for it does require considerable intelligence to succeed in opera, in spite of opinions to the contrary expressed by many. Others, who have keen and alert minds and voices of fine quality, yet lack that certain esprit and broadness of musical outlook required in a great artist. This lack is often so apparent in the person’s manner or bearing that I am tempted to tell him it is no use before he utters a note. Yet it would not do to refuse a hearing to all these misfits, for there is always the chance of encountering the unknown genius, however rare a bird he may be.

And how often have the world’s great voices been discovered by chance, but fortunately by some one empowered to bring out the latent gift!

On April 20, 1914, Caruso teamed with one of the foremost female sopranos of the day, Alma Gluck (born Reba Feirsohn in Romania), on a duet recording of Libiamo ne’ lieti calici (Brindisi–Drinking song), from Verdi’s La Traviata

One finds in America many beautiful voices, and when one thinks of the numerous singers successfully engaged in operatic careers both here and abroad, it cannot with justice be said as it used to be several years ago that America does not produce opera singers. Naturally a majority of those to whom I give a hearing here in New York are Americans, and of these are a number of really remarkable voices and a fairly good conception of what is demanded of an opera singer.

Sometimes, however, it would be amusing if it were not tragic to see how much off the track people are who have been led to think they have futures. One young man who came recently to sing for me carried a portentous roll of music and spoke in the deepest of bass voices. When asked what his main difficulty was he replied that he “didn’t seem to be able to get on the key.” And this was apparent when he started in and wandered up and down the tonal till he managed to strike the tonic. Then he asked me whether I would rather hear “Qui sdegno,” from Mozart’s “Magic Flute,” or “Love Me and the World is Mine.” Upon the latter being chosen he asked the accompanist to transpose it, and upon this gentleman’s suggesting a third lower, he said: “No, put it down an octave.” And that’s where he sang it, too. I gently but firmly advised the young man to seek other paths than musical ones. However, such extreme examples as that are happily rare.

I would say to all young people who are ambitious to enter on a career of opera: Remember, it is a thoroughly hard-worked profession, after all; that even with a voice of requisite size and proper cultivation there is still a repertory of rôles to acquire, long months and years of study for this and requiring a considerable feat of memory to retain them even after they are learned. Then there is the art of acting to be studied, which is, of course, an entire occupation in itself and decidedly necessary in opera, including fencing-how to fall properly, the various gaits and gestures wherewith to portray different emotions, etc. Then, as opera is sung nowadays, the knowledge of the diction of at least three languages-French, German and Italian-if not essential, is at least most helpful.

Caruso in the 1918 silent film My Cousin, playing a dual role, that of famous opera singer (Cesare Caroli) and his cousin, an impoverished sculptor. The piano accompaniment was recorded in July 2011 by Glenn Amer, (singer/pianist and Caruso aficionado). The accompaniment was recorded in one take–completely improvised and arranged by Mr. Amer using operatic tunes and popular songs (mostly taken from Caruso’s repertoire). All the links and other bits are also improvised.(hammondmania, YouTube)

The Career of Enrico Caruso

How a Neapolitan Mechanic’s Son Became the World’s Greatest Tenor

Enrico Caruso enjoys the reputation of being the greatest tenor since Italo Campanini. The latter was the legitimate successor of Brignoli, an artist whose wonderful singing made his uncouth stage presence a matter of little moment. Caruso’s voice at its best recalls Brignoli to the veteran opera habitué. It possesses something of the dead tenor’s sweetness and clarity in the upper register, but it lacks the delicacy and artistic finish of Campanini’s supreme effort, although it is vastly more magnetic and thrill inspiring.

That Caruso is regarded as the foremost living tenor is made good by the fact that he is the highest priced male artist in the world. Whenever and wherever he sings multitudes flock to hear him, and no one goes away unsatisfied. He is constantly the recipient of ovations which demonstrate the power of his minstrelsy, and his lack of especial physical attractiveness is no bar to the witchery of his voice.

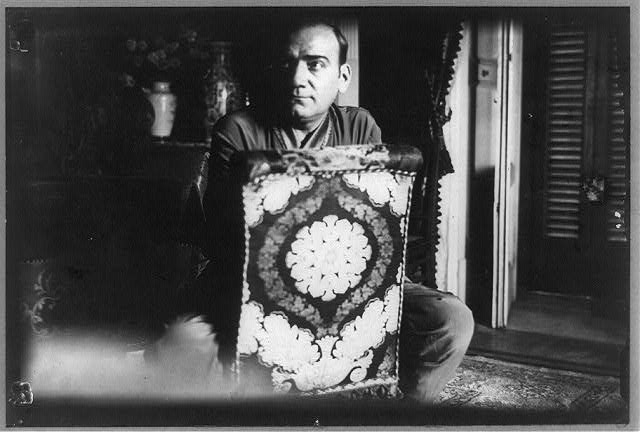

Enrico Caruso examines a bust sculpture of himself, August 5, 1914 (Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Caruso is a Neapolitan and is now thirty-five years of age. Unlike so many great Italian tenors, he is not of peasant parentage. His father was a skilled mechanic who had been put in charge of the warehouses of a large banking and importing concern. As a lad Enrico used to frequent the docks in the vicinity of these warehouses and became an expert swimmer at a very early age. In those halcyon days his burning ambition was to be a sailor, and he had a profound distaste for his father’s plan to have him learn a trade.

At the age of ten he was still a care free and fun loving boy, without a thought beyond the docks and their life. It was then that his father ruled that since he would not become a mechanic he must be sent to school. He had already learned to read a little, but that was all. He was sent to a day school in the neighborhood, and he accepted the restraint with such bad grace that he was in almost constant disgrace. His long association with the water front had made him familiar with the art of physical defense, and he was in frequent trouble on that account.

From Caruso’s final recording session, Camden, NJ, September 16, 1920, the sacred piece ‘Domine Deus’ from Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle.

The head master of the school was a musician, and he discovered one day that his unruly pupil could sing. He was an expert in the development of the boy soprano and he soon realized that in young Caruso he had a veritable treasure. He was shrewd enough to keep his discovery to himself for some time, for he determined to profit by the boy’s extraordinary ability. The lad was rehearsed privately and was stimulated to further effort by the promise of sweetmeats and release from school duties. Finally the unscrupulous master made engagements for the young prodigy to sing at fashionable weddings and concerts, but he always pocketed the money which came from these public appearances.

At the end of the second year, when Caruso was twelve years of age, he decided that he had had enough of the school, and he made himself so disagreeable to the head master that he was sent home in disgrace. His irate father gave him a sound thrashing and declared that he must be apprenticed to a mechanical engineer. The boy took little interest in his new work, but showed some aptitude for mechanical drawing and calligraphy. In a few months he became so interested in sketching that he began to indulge in visions of becoming a great artist.

Caruso’s first and last recordings: ‘Studenti ! Udite’ from the opera Germania by Alberto Franchetti. Recorded at the Grand Hotel, Milan, with piano accompaniment by Salvatore Cottone on Friday, April 11, 1902. And his last recording from Thursday, September 16, 1920: Crucifixus, from Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle (Posted at YouTube by Tom Frøkjær)

When he was fifteen his mother died, and, since he had kept at the mechanical work solely on her account, he now announced his intention of forsaking engineering and devoting himself to art and music. When his father heard of this open rebellion he fell into a great rage and declared that he would have no more of him, that he was a disgrace to the family and that he need not show his face at home.

So Caruso became a wanderer, with nothing in his absolute possession save a physique that was perfect and an optimism that was never failing. He picked up a scanty livelihood by singing at church festivals and private entertainments and in time became known widely as the most capable boy soprano in Naples. Money came more plentifully, and he was able to live generously. In a short time his voice was transformed into a marvelous alto, and he soon found himself in great demand and was surfeited with attention from the rich and powerful. It was about this time that King Edward, then Prince of Wales, heard him sing in a Neapolitan church and was so delighted that he invited the boy to go to England, an invitation which young Caruso did not accept. Now that he had “arrived” Naples was good enough for him.

One day something happened which plunged him into the deepest despair. Without a warning of any sort his beautiful alto voice disappeared, leaving in its place only the feeblest and most unmusical of croaks. He was so overcome at his loss that he shut himself up in his room and would see no one. It was the first great affliction he had ever known, and he admits that he meditated suicide. He had made many friends, and some of them would have been glad to comfort him, but his grief would admit of no partnership.

One evening when he was skulking along an obscure highway, at the very bottom of the well of his despair, a firm hand was laid on his shoulder and a cheery voice called out: “Whither so fast? Come home with me, poor little shaver!”

It was Messiani, the famous baritone, who had always felt an interest in the boy and who would not release him in spite of his vigorous efforts to escape. The big baritone took him to his lodging and when he had succeeded in cheering the unhappy lad into a momentary forgetfulness of his misery asked him to sing.

“But I can’t,” sobbed Caruso. “It has gone!”

Caruso does Cohan: the great Enrico in a rare English language recording, of George M. Cohan’s ‘Over There,’ recorded July 10, 1916. Caruso performed the song at a few War Bond rallies in the States after his future wife, Dorothy Park Benjamin, had instructed him in the English pronunciation. He also sings a verse and chorus in German, for good measure.

Messiani went to the piano and struck a chord. The weeping boy piped up in a tone so thin and feeble that it was almost indistinguishable.

“Louder!” yelled the big singer, with another full chord. Caruso obeyed and kept on through the scale. Then Messiani jumped up from the piano stool, seized the astonished boy about the waist and raised him high off his feet, at the same time yelling at the top of his voice: “What a little jackass! What a little idiot!”

Almost bursting with rage, for the miserable boy thought his friend was making sport of him, Caruso searched the apartment for some weapon with which he might avenge himself. Seizing a heavy brass candlestick, he hurled it at Messiani with all his force, but it missed the baritone and landed in a mirror.

“Hold, madman!” interposed the startled singer. “Your voice is not gone. It is magnificent. You will be the tenor of the century.”

Messiani sent him to Vergine, then the most celebrated trainer of the voice in Italy. The maestro was not so enthusiastic as Messiani, but he promised to do what he could. He offered to instruct Caruso four years, only demanding 25 per cent. of his pupil’s receipts for his first five years in opera. Caruso signed such a contract willingly, although he realized afterward that he was the victim of a veritable Shylock.

When Vergine was through with the young tenor he dismissed him without lavish commendation, but with a reminder of the terms of his contract. Caruso obtained an engagement in Naples, but did not achieve marked success at once. On every payday Vergine was on hand to receive his percentage. His regularity finally attracted the attention of the manager, and he made inquiry of Caruso. The young tenor showed him his copy of the contract and was horrified to be told that he had bound himself to his Shylock for a lifetime; that the contract read that he was to give Vergine five years of actual singing. Caruso would have reached the age of fifty before the last payment came. The matter was finally adjusted by the courts, and the unscrupulous teacher lost 200,000 lire by the judgment.

Enrico Caruso in his last portrait, dressed in pajamas, in his apartment at the Hotel Vesuve in Naples, where he died on August 2, 1921, a few days after R. Carbone took this photograph. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

In Italy every man must serve his time in the army, and Caruso was checked in his operatic career by the call to go into barracks. Not long, however, was he compelled to undergo the tedium of army life. In consideration of his art he was permitted to offer his brother as a substitute after two months, and he returned to the opera. He was engaged immediately for a season at Caserta, and from that time his rise has been steady and unimpeded. After singing in one Italian city after another he went to Egypt and thence to Paris, where he made a favorable impression. A season in Berlin followed, but the Wagner influence was dominant, and he did not succeed in restoring the supremacy of Italian opera. The next season was spent in South America, and in the new world Caruso made his first triumph. From Rio he went to London, and on his first appearance he captured his Covent Garden audience. When he made his first appearance in the United States he was already at the top of the operatic ladder, and, although many attempts to dislodge him have been made, he stands still on the topmost rung.

From the book Caruso and Tetrazzini on The Art of Singing, by Enrico Caruso and Luisa Tetrazzini (Metropolitan Company, Publishers; New York, 1909). Available free online at Project Gutenberg.