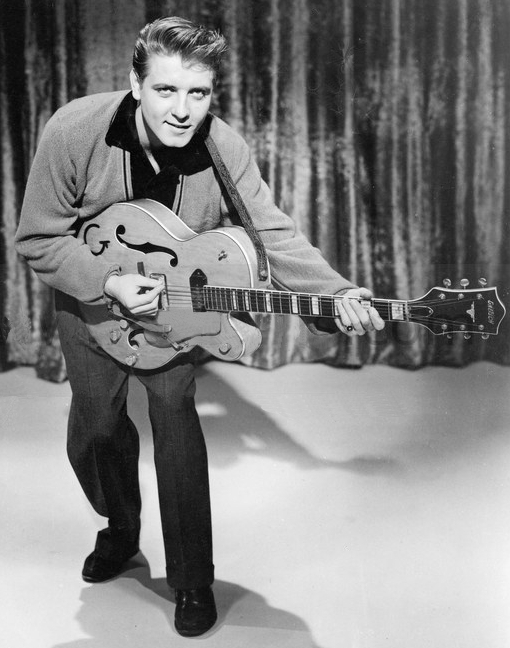

Eddie Cochran: ‘We were looking for a hit that would give Eddie some identity,’ Eddie Cochran’s co-writer/manager Jerry Capehart recalled of the session that yielded ‘Summertime Blues’

Lyrics in search of a riff, a riff in search of lyrics, an artist in search of identity…and Amos ‘n’ Andy. Put ’em together and whatta ya got? In this case, Eddie Cochran’s original version of “Summertime Blues,” still the sine qua non of summer songs, 53 years later. Unlike the other summer-themed hit from 1958, the Jamies’ “Summertime Summertime,” a driving, doo-wop indebted paean to the joys of slipping the surly bonds of academia for fun in the sun, “Summertime Blues” dared suggest a darker side to v-a-c-a-t-i-o-n, and used a hard-flailed, angry two-chord guitar riff, a thumping ostinato bass lick, and double-timed handclaps to burn its message into rock ‘n’ roll lore.

When Cochran and his manager/co-writer Jerry Capehart wrote the song at Capehart’s Sunset Boulevard apartment in Los Angeles in March of 1958, the artist, then only 17 but a professional for nearly four years, was going nowhere fast. He had managed a modest hit in 1957 with a version of John D. Loudermilk’s “Sittin’ In the Balcony,” which did little beyond proving that with a lot of reverb Cochran could pull off an agreeable emulation of Elvis Presley’s hiccuping vocal style and that as a guitarist he had mastered Carl Perkins’s razor-edged sound signature.

Eddie Cochran and Jerry Capehart at the ‘Summertime Blues’ session at Gold Star Studios. Engineer Larry Levine is visible behind the control room window, along with Cochran’s girlfriend, songwriter Sharon Sheeley, who wrote Ricky Nelson’s first #1 hit, ‘Poor Little Fool.’

The writing session at Capehart’s apartment was intended to correct that problem. “We were looking for a hit that would give Eddie some identity,” Capehart recalled in what was his final interview, conducted by this reporter in 1998 shortly before Capehart was diagnosed with brain cancer, to which he succumbed on June 7 of that year. Cochran came over with his bass player, Connie “Guybo” Smith, in tow, intending to work out arrangements on three songs for an upcoming recording session. “We went through them all, and after we’d finished I looked at Eddie and Eddie looked at me, and he said, ‘Dad, I don’t think we’ve got anything here.'”

Eddie Cochran, ‘Summertime Blues’ live on Town Hall Party, 1958

Capehart agreed and then ran an idea past Cochran: “You know, Eddie, there’s never been a blues song written about the summertime. Let’s write a song called ‘Summertime Blues.’ And he said, “Hey, I’ve got this new riff on the guitar.’ And he went, da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da, you know, that was the new riff. Forty-five minutes later it was all over–those lyrics just rolled out. Had the song as you hear it today.” Asked if Cochran had written any of the lyrics, Capehart says, “He contributed a couple of words here and there. Basically I wrote the lyrics and he had the guitar lick.”

As to the lyrics themselves, which describe a young man butting heads with adult authority figures (his parents, his boss at work, his Congressman) who are doing their best to keep him from living the good life (basically dating and driving), Capehart says he wasn’t trying to raise a fuss or a holler but merely seeking the Grail: “We were just trying to hit the commercial market, just trying to get a hit record. As far as we were concerned, the way there was to go with basically what we were listening to on the radio. Trying to get in the pocket somewhere.” No message.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=21SnR2WHNos

The classic single, released on July 21, 1958, peaked at #8 on the Billboard Hot 100 in September.

The recording session, at Gold Star Studios (which would later enter legend as Phil Spector’s studio of choice in the 1960s) was intended to produce only a demo of the song. Capehart paid $350 for three hours of studio time and for a drummer sent over by the Los Angeles Musician’s Union to accompany guitarist Cochran and, on bass, Smith. Capehart could not recall remember much about the drummer–including his name–except that “he couldn’t hold tempo; he was bad. And Eddie was about to go nuts. We got the one take–the one you hear on the record–everything else we had to trash. Thirty, thirty-five takes.” (A Capehart obituary published in The Independent of June 18,1998, quotes the songwriter as naming New Orleans legend Earl Palmer as the drummer on all the important Cochran sessions, including “Summertime Blues.” Earl Palmer, however, never had a problem holding tempo.)

During the recording, Cochran had a brainstorm. Capehart had written the adults’ put-down lines (“I’d like to help you, son, but you’re too young to vote”) intending them to be played straight. Cochran, who was given to quoting pet phrases uttered by Tim Moore’s George “Kingfish” Stevens character on the Amos ‘n’ Andy TV show (“His favorite expression was ‘I not only resents the allegation; I resents the alligator.’ That was Eddie’s thing,” Capehart claims), had the idea to do the put-down lines in Kingfish’s voice. These were recorded separately and spliced into the finished track, as were the double-time handclaps coming on every other beat, courtesy Cochran, Capehart, Smith and Gold Star engineer Larry Levine.

Brian Setzer as Eddie Cochran performing a snippet of ‘Summertime Blues’ in director Luis Valdez’s Ritchie Valens biopic, La Bamba (1987)

Also in a 1998 interview with this reporter, Levine (who died on May 8, 2008) downplayed his role in the clean, robust sound of the finished track, which stands up to the work he did in later years with Spector. “I can’t take any credit for the sound other than what we had in the studio,” he insisted. “At Gold Star we were working off spit and chewing gum. We would put things together just to make them work. Back in those days mostly what we were using as far as microphones, and I’m sure what we used on guitar, was an Electro Voice 256. That’s Eddie doing all that. The only thing I didn’t do is screw it up. To me that’s what a good engineer does.”

When the session ended, Capehart was sure they had found the elusive hit. Cochran agreed, saying only, “Dad, I think we got one”–“which was a lot for him,” Capehart noted.

Released in May of 1958, the single peaked at Number Eight on the Billboard Singles chart in August. Less than two years later Cochran was dead, from massive head injuries sustained in a car wreck in England (Gene Vincent was injured in the same crash). Toward the end of his life, Cochran, long haunted by premonitions of an early death, had taken to signing autographs with the sentiment, “Don’t forget me.”

Eddie can rest in peace.