If I told you animals get human illnesses like cancer or heart disease, you might respond with something like “Well, of course, Captain Obvious—our beloved dog Percy died of cancer, and the neighbors across the street have a cat with a heart problem.”

But if I told you animals are also known to grapple with such other human challenges as addiction, eating disorders and suicidal tendencies, you might respond with something like “That’s crazy talk—sounds like you’re grappling with an addiction problem. Put a lid on this nonsense, unless you can show me a credible book that proves this stuff.”

A little scorched by that response, frankly, I present to you Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human And Animal Health, an acclaimed New York Times bestseller, co-authored by Barbara Natterson-Horowitz–a cardiologist at the UCLA Medical Center and professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA—and Kathryn Bowers, an accomplished journalist, editor and science writer.

First published in June of 2012, Zoobiquity elicited enthusiastic reviews from a slew of major publications and blogs—and equally enthusiastic praise from Ph.Ds including autistic animal wiz Temple Grandin and such M.D.s as noted surgeon/New Yorker medical writer Atul Gawande.

The book was issued in paperback in April, providing an ideal opportunity to discuss it with Natterson-Horowitz and Bowers on the May 22 edition of Talking Animals. I figured it was pretty difficult to talk about the world of Zoobiquity without asking about the term Zoobiquity.

“I’m a cardiologist,” Natterson-Horowitz responded. “I take care of human patients with heart attacks and high cholesterol. Some years ago, I was given this wonderful opportunity to spend time with veterinarians working at the Los Angeles Zoo. And there, I began hearing the veterinarians talking about congestive heart failure in a gorilla. Or breast cancer in a jaguar. Or obsessive-compulsive disorder in a bear.

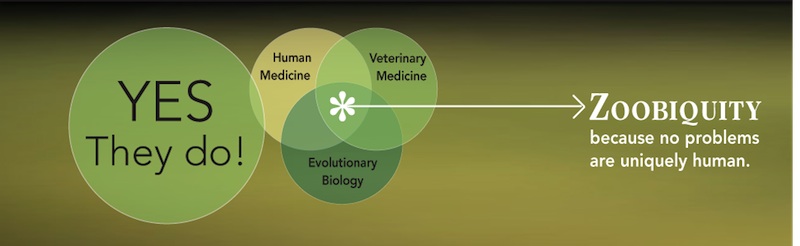

“And it struck me that in all my years of practicing human medicine, it had never occurred to me that the diseases I was taking care of in my human patients were the same as the diseases veterinarians were taking care of in their animal patients. Kathryn Bowers and I started working on this idea of: What would happen if human medicine got closer to veterinary medicine, and we began looking at our patients as human animals? What insights would they have for us?

“So we were working away on this idea, and we were also very interested in the idea of how evolutionary biology might also help us understand common human medical problems, but we couldn’t find a word to describe this fusion of fields. So we coined our own: ‘zoo,’ which is Greek for ‘animal’ and ‘ubiquity,’ which is Latin for ‘everywhere’—and came up with ‘Zoobiquity.’”

In chapter after chapter, Zoobiquity draws fascinating, often revelatory, parallels between animal health and human health. And early on, the authors make it clear that exploring these similarities and connecting these medical/veterinary dots is not remotely related to animal testing or any sort of experimentation on animals.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bc213YHoB-Y

An ABC News report on Zoobiquity, with author-cardiologist Barbara Natterson-Horowitz

Indeed, one of the more intriguing and appealing aspects of the Zoobiquity ideology is that the findings along the human-animal axis aren’t just intended to improve human health, but to travel in both directions.

“Absolutely,” Natterson-Horowitz agreed, “and the thing that I found eye-opening and thrilling as a physician to encounter—frankly, for the first time—was what we physicians call ‘spontaneously occurring diseases.’

“These are problems that just happen to an animal, or a human animal, in the course of their life. But these things were happening all the time in the wild, in the oceans, in the sky, animals are born with birth defects sometimes, just like humans are sometimes born with birth defects.

“And animals have long bone fractures, and they may develop cancer and they may have trauma, they may develop kidney failure. These things occur naturally. There are hundreds of millions to billions of animals living at any moment on earth, and not all of them are completely healthy.

“So there’s so much knowledge that we could gain just from understanding and aiding animals amongst us in our homes and again in the wild, who have many of the same disorders we have.”

A half-hour conversation with Zoobiquity co-author Barbara Natterson-Horowitz on The Agenda with Steve Paikin

Echoing her colleague, Bowers jumped in to add: “And that’s why we look so closely at wildlife biologists and wildlife veterinarians for their work out in the field—we’re explicitly not looking at research on lab animals. We’re looking for what people knew about wild animals and pets.”

And, boy, does that amount to a doozy—information about maladies and behavior that even some longtime animal lovers and experts of various stripes would surely find jarring. For instance, it turns out that members of the animal kingdom like to catch a buzz.

If this tidbit has prompted you to let your imagination run wild picturing monkeys guzzling cocktails, dogs tripping and—getting really fanciful here—wallabies digging an open-air opium den, let me just say there’s no imagination necessary. These are all factual instances; these all happen.

Natterson-Horowitz and Bowers address these examples in Zoobiquity (they report on a BBC video shot on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, where resident monkeys steal half-consumed drinks from a hotel bar, then exhibit all signs of being soused), and in the Talking Animals conversation—which not only serves as startling and compelling information at face value, but also for the significant implications raised by all sorts of creatures seeking mind-altering substances, often with what we might wryly call dogged determination.

At TEDx Talks, cardiologist-author Barbara Natterson-Horowitz discusses the human-animal connection as she sees it in her daily work with primate and non-primate patients.

Good luck hanging on to your position if you’re someone who stigmatizes addicts, moralizes about the disease, or just tends to be judgmental about the use of alcohol and drugs, feeling it signals human weakness. I observed as much in my on-air chat with Natterson-Horowitz and Bowers.

“It’s kind of gratifying that you would say that,” Natterson-Horowitz said, “because as Kathryn and I were doing our research and moving through this book, we were struck by how often we would encounter problems that animals might have that were the kinds of problems my patients felt guilty about, ashamed about–they, or maybe their families or parents would be blaming themselves for.

“And knowing that this was happening in dogs and cats and lions and bears and kangaroos was a very powerful insight, in the case of substances let’s say. So it turns out that wild animals—this has been noted by naturalists for decades—sometimes seek out psychoactive substances.

“For example, there are bighorn sheep that in the Canadian Rockies who really like this hallucinogenic lichen that grows at the top of these cliffs, and will scale these very step rocks to get to this lichen, and will grind their teeth sometimes down to the gums just to access it.

“Or there are wallabies in Tasmania, and Tasmania is one of the world’s largest producers of medical grade opium. There are huge fields of poppies and although the farmers enclose these fields with barbed wire fences, some of the wallabies will risk life and limb, literally, to jump over these fences and access the poppy sap and poopy straw. And they get high. And some of them keeping going back, and meet their demise that way.

“And we have many other examples. There are certain dogs that really like licking toads, ‘cause there’s this hallucinogenic substance or euphorigenic substance on the skin of the toad. We have many examples of animals that seek out substances.

“There are even birds, these waxwing birds, some of them are in California, some are in Europe, and they are notorious for seeking out fermented berries. They will fly over certain trees that have berries that aren’t fermented, and they want to access the fermented berries, and when they get to them, they gorge. And then they become intoxicated and sometimes they have been seen flying in an erratic fashion, what’s called ‘flying while intoxicated.’ So there are many examples of that.”

Zoobiquity brims with examples of similarly illustrative dovetailing between the lands of animal and human medicine/health—hours and hours of teachable moments—and often times with arguably broader implications than the cross-species powerful pull of intoxication. Like cancer. Heart disease. Sexually transmitted diseases. Fainting. Obesity. Many others.

Zoobiquity co-author Kathryn Bowers: ‘…just realizing that cancer is something that has around since the age of the dinosaur, and probably before, took some of the pressure off of being human.

If the impact of Zoobiquity hasn’t quite yet triggered a tidal wave of change in the medical (and veterinary) professions, it has caused a good-sized ripple that appears to be building. For one thing, the release of the paperback edition has elicited a new raft of major media coverage.

For another, there are the Zoobiquity conferences, in which top clinicians and scientists in both human and veterinary medicine gather to discuss the same diseases in humans and across animal species, followed by “Walk Rounds” at the Los Angeles Zoo; there have been two such conferences held in L.A, in 2011 and 2012, while the 2013 conference will take place in November in New York, with the “Walk Rounds” happening at the Bronx Zoo.

The substantive discussion that occur at these confabs and after–and surrounding these confabs, for that matter—has forged a much wider and deeper understanding amongst veterinarians and physicians, and fostered a greater respect between those camps. Which is saying something, given the monolithic arrogance that can emanate from M.D.s.

“Unfortunately, my profession–which has so many wonderful attributes–there are some negatives,” Natterson-Horowitz acknowledged. “Unfortunately, there has been a kind of hierarchical viewpoint I think that human medicine has had, particularly when it comes to veterinary medicine. I do think that’s changing.

“Some physicians might be interested to know that it’s harder to get into veterinary school than medical school—there are far, far fewer vet schools in the country than med schools. The training is very, very much overlapping.

‘There are certain dogs that really like licking toads, ‘cause there’s this hallucinogenic substance or euphorigenic substance on the skin of the toad. We have many examples of animals that seek out substances.’

“It’s really interesting as a cardiologist to hang around with veterinary cardiologists; we completely speak the same language. I have more in common with a veterinary cardiologist, in terms of what I can talk about, than with a human oncologist. It’s the same language, vocabulary and diseases. So, I think things are changing—we hope to accelerate that change.”

Clearly, change represents the watchword of the zoobiquity universe–Natterson-Horowitz and Bowers are not merely documenting this profound change, but helping create it. As well as feeling it very personally.

Having asked Natterson-Horowitz a number of questions about how she perceived the zoobiquity change amidst her direct colleagues, amidst the medical profession at large, and in her own career—I asked Bowers how the zoobiquity experience has affected her work and how she approaches what she does.

“I would say,” Bowers replied, “it’s changed the way I view the world, and my place in it. Not to put too fine a point on it. Realizing how connected we all are to every other living thing has been eye-opening. And also just realizing that the evolution that we talk about that connects us to our deep past is something that happens every minute of every day.

“So we are connected to what’s around us at the moment, and also in the past. Barbara and I, in doing our research, found articles about dinosaur cancer. And just realizing that cancer is something that has around since the age of the dinosaur, and probably before, took some of the pressure off of being human.” She laughs here.

“It sometimes seems,” Bowers continues, “that we bring illness and disease upon ourselves, with our bad human habits, and of course there are things we can do that amplify our risks. But disease and health is really just part of being a human animal on earth, and I find something really comforting and connecting about that.”

Taking the liberty of speaking on behalf of other animals—very much including all talking animals–same here, Kathryn. Same here.

Click here to access the Talking Animals interview with Barbara Natterson-Horowitz & Kathryn Bowers.